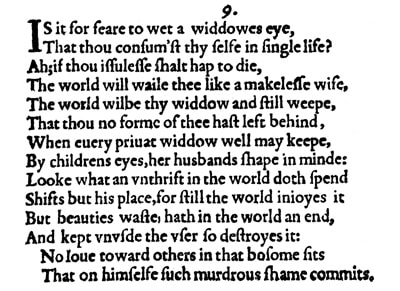

Sonnet 9: Is it for Fear to Wet a Widow's Eye

|

Is it for fear to wet a widow's eye

That thou consumest thyself in single life? Ah, if thou issueless shalt hap to die The world will wail thee, like a makeless wife; The world will be thy widow and still weep That thou no form of thee hast left behind When every private widow well may keep By children's eyes her husband's shape in mind. Look what an unthrift in the world doth spend, Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it, But beauty's waste hath in the world an end, And, kept unused, the user so destroys it: No love toward others in that bosom sits That on himself such murderous shame commits. |

|

Is it for fear to wet a widow's eye

That thou consumest thyself in single life? |

Is it because you are afraid to make a prospective widow cry that you use yourself up as a single man?

The question is, of course, rhetorical. Shakespeare asks the young man whether possibly the actual reason why he isn't marrying is that he simply wants to spare a hypothetical widow, who would be left behind after his death, her sadness. The use of the word "consumest thyself" is, however, once more suggestive. It evokes the idea of somebody eating or using themselves up, and once or twice before we had more than a bit of a hint that the poet is admonishing the young man for not only 'using' himself' – whatever that might entail – but for 'abusing' himself, in a sexual way. PRONUNCATION: Note that consumest is here pronounced with two syllables: con-sum'st. The Quarto Edition in fact spells it with an apostrophe and most editors retain this, but see Text Note for an explanation of the conventions applied here. |

|

Ah, if thou issueless shalt hap to die,

The world will wail thee, like a makeless wife; |

Ah! If you should happen to die without children – issueless meaning without issue, in other words childless – then the whole world will cry for you – "wail thee" – like a wife who doesn't have a husband, a "makeless wife."

"Makeless" means without a 'mate' in the matrimonial sense. And, of course, 'wife without a husband', one might argue, is not a wife, but... |

|

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind, |

...here comes the explanation: the whole world will be your widow and still – meaning both forever and also in spite of having tried to prevent this from happening by never marrying – cry over the fact that you have not left behind a likeness or, as we would today perhaps venture, 'copy' of yourself, though this is not meant to be an 'identical copy', of course, because we're always talking about a child, who can at best be an iteration of a parent. But this idea of the son being effectively a continuation of the young man has by now been well established.

|

|

When every private widow well may keep

By children's eyes her husband's shape in mind. |

And this when in fact every individual or 'personal' widow will be able to remind herself of her deceased husband by looking at her children, or, perhaps more specifically, by looking into her children's eyes.

The use of the word 'private' here is particularly interesting. We have noted before that anyone of high status in Shakespeare's world is almost by definition a public or at least semi-public figure, and we have come to the conclusion that the young man whom these poems are addressed to clearly must have a fairly high social status. And so while the 'private' here certainly stands to mean a widow who is an individual person as opposed to the metaphorical widow that is the world, it also juxtaposes this hypothetical person with a woman of status, and thus with a potential person who would be widow to this young man, because he would almost certainly have to marry a woman of status, and even if he didn't, any woman he were to marry would immediately be raised in status close to his level, simply by virtue of the fact that she is then his wife. What we have also had before is a similar case to this where "the lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell" was used to describe the young man's face: 'gaze' stood in for that which is in fact 'gazed on'. Here now the "children's eyes" are effectively standing in for the children themselves and more specifically for their faces. This is most likely a more suitable reading than taking the 'eyes' literally here and suggesting that a widow can keep her husband's shape in mind through looking into their children's eyes. |

|

Look what an unthrift in the world doth spend

|

See what happens to what a wasteful person spends in the world...

An 'unthrift' is someone who is not thrifty, in other words not mindful of how they spend their wealth, and we are reminded here of Sonnet 4, where the poet addressed the young man as an "unthrifty loveliness". |

|

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it,

|

...the money that has been spent by the wastrel will simply circulate and go from one person and place to another, because the world that now has his money can always continue to enjoy it.

Noteworthy is that the 'his' here, as every so often in Shakespeare, works as 'its', referring to what the unthrifty spends in the world: we would say: 'shifts only its place', It is worth bearing in mind in this context that money in Shakespeare's day is essentially coins, and they literally pass from one person and therefore place to another. |

|

But beauty's waste hath in the world an end,

|

A wonderfully complex line, this, which has several potential meanings and illustrates once again just how skilfully crafted these poems are:

Wasted beauty – by implication such as the young man's – eventually runs out, there is an end to it. That is the most simple and basic reading, and we know of course that the poet has told the young man on several occasions already that he is being wasteful with his beauty, so we can quite safely assume that it applies. But we were just reminded of Sonnet 4, where I, the poet, called you, the young man, an "unthrifty loveliness," and asked "why do you spend upon thyself thy beauty's legacy?" And there we got the impression that Shakespeare was coming very close to telling the young man to stop pleasuring himself and instead get on with it and make a woman pregnant. We also shied away somewhat from expressing it quite so crudely and directly, but here now is another insinuation that can't be quite ignored. Because if we were to allow for beauty's waste to have the additional meaning of that which the beauty – the young man – is physically wasting – his semen, then we can also allow for "hath in the world an end" to mean 'has a purpose in the world', as in 'to what end do you use this procreation potential of yours?' 'Why, to make children, of course!' And this reading is somewhat corroborated by how the line continues: |

|

And, kept unused, the user so destroys it:

|

On the surface, much as we would expect, this means: And the person who should be using his beauty to attract a suitable wife, by not doing so and thus keeping this beauty unused, eventually destroys it, by letting it go to waste and remaining childless.

On the subsidiary level though, and entirely congruent with what has gone before, we can also understand: but the user – as in 'self-abuser' – by keeping his effusions unused – by not putting them to their original purpose, which is to make a woman pregnant – destroys them, turning them into waste. |

|

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murderous shame commits. |

No love can be residing in the heart of someone who commits such a shameful deed on himself.

And again we have multiple layers: "Murderous shame" is by many editors interpreted as 'shameful murder' but it is debatable how useful this reading is, since it makes it necessary to accept the destruction of beauty as a type of 'murder'. Whereas the "on himself" once again puts forward the idea of an act that the young man commits directly – as the words suggest – on himself. And it is 'murderous' because it does lead to the children that should be born to him never being conceived, but also because it comes close to a deadly sin, namely lust. And lust that you commit on yourself is, of course, again, masturbation. And what, but what exactly, has "love" got to do with it, got to do with it?... PRONUNCIATION: Note that toward is here pronounced as one syllable: t'ward and murderous as two syllables: mur-d'rous. |

The multi-layered and marvellously complex Sonnet 9 sets out with an unlikely supposition to make some strongly suggestive statements about the young man and his conduct and introduces a whole new, massive, and massively important, concept to these poems.

Superficially, it can be read as yet another iteration of the principal thought that runs through all the Procreation Sonnets, that the young man, by not having any children, is wasting his beauty. The deployment of the vocabulary though is as precise as it is laden with undertones that – especially when read in the context of the other instances so far where the poet has used the same words – are quite obviously sexual. "Consumest thyself" and "murderous shame" that somebody "commits" "on himself" are the strongest contenders, but "beauty's waste" too has its potential to evoke additional shades of meaning.

It is absolutely worth reiterating though that we may be reading more into these sonnets than the writer intended. How likely though is this to be the case? I would argue not all that likely. Let us remind ourselves what these first seventeen sonnets do: they tell a young man to produce a child. We've so far learnt a few things about the young man which we will summarise again soon, but perhaps not here, since we did so recently, and this sonnet itself doesn't tell us anything new about him, but certainly the impression we are getting is of a fairly headstrong, somewhat self-obsessed, on all accounts beautiful and sexually active young man. And the only way in Shakespeare's day you can produce a child is by having sex. So if sex features in these sonnets by being alluded to, even referred to, if the poet appears to observe that the young man, in order to have a child, really has to start putting his sexual activity to a more targeted use than he seems to be doing, then none of this needs to either surprise or scandalise us. We have noted before how viscerally lives are lived in Elizabethan England, and it is also worth noting that neither Shakespeare nor his contemporaries are all that squeamish about sex. No society in which men wear codpieces can be.

And so possibly one of the most interesting things that Sonnet 9 does is remind us that we in our society – I am talking quite specifically about Britain, Western Europe and North America in the third decade of the 21st century – are probably more prudish, more moralistic, more, ironically, worked up and sensitive about the earthy, fleshy, raunchy sexiness of sex than Shakespeare, his young man, and their contemporaries were. And indeed, as we are soon to find out, about sexuality. But that has not really come into play yet, and we want to go by what the words themselves tell us in these sonnets, both case-by case and cumulatively, and so talking about sexuality and gender at this point would be jumping the gun by several blows.

But one more thing seems to occur, and this – again – may or may not be based in fact: it is but an impression. It is nevertheless an impression and if it were to turn out to be correct it would be significant enough: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, seem to be getting more daring, more bold. Whether that's because I'm getting bored with my task or whether it is that I am getting to know the young man, we don't know, but there is one critical, crucial, categorically important word that we haven't even mentioned yet, and it features here for the first time in this sequence: love. "No love toward others in that bosom sits," I say, and this is the first time in this, the traditionally accepted, originally published sequence, that we get the word 'love'. Nine sonnets in, in the penultimate line.

Is this significant? Of course it is. If nothing else, the fact alone that it has taken the poet this long to introduce the concept of 'love' is telling. So far, we've had a "lovely April" in Sonnet 3, we've had the young man addressed as an "unthrifty loveliness" in Sonnet 4, and in Sonnet 5 he became, by an intriguing poetic device, "the lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell." But nobody has mentioned 'love' before. Marriage, yes. Making children? Yes. 'Using' your beauty? Yes. 'Wasting' your beauty? Absolutely. But LOVE?...

This is the first time we hear of it, and so of course we are entitled to ask the Tina Turner question: just what exactly has love got to do with it all? For the poet? For the young man? For the young man's potential wife and mother of his still, as yet, potential children?

This sonnet does not tell us. But we stand a fair chance of finding out more as we continue our journey...

Superficially, it can be read as yet another iteration of the principal thought that runs through all the Procreation Sonnets, that the young man, by not having any children, is wasting his beauty. The deployment of the vocabulary though is as precise as it is laden with undertones that – especially when read in the context of the other instances so far where the poet has used the same words – are quite obviously sexual. "Consumest thyself" and "murderous shame" that somebody "commits" "on himself" are the strongest contenders, but "beauty's waste" too has its potential to evoke additional shades of meaning.

It is absolutely worth reiterating though that we may be reading more into these sonnets than the writer intended. How likely though is this to be the case? I would argue not all that likely. Let us remind ourselves what these first seventeen sonnets do: they tell a young man to produce a child. We've so far learnt a few things about the young man which we will summarise again soon, but perhaps not here, since we did so recently, and this sonnet itself doesn't tell us anything new about him, but certainly the impression we are getting is of a fairly headstrong, somewhat self-obsessed, on all accounts beautiful and sexually active young man. And the only way in Shakespeare's day you can produce a child is by having sex. So if sex features in these sonnets by being alluded to, even referred to, if the poet appears to observe that the young man, in order to have a child, really has to start putting his sexual activity to a more targeted use than he seems to be doing, then none of this needs to either surprise or scandalise us. We have noted before how viscerally lives are lived in Elizabethan England, and it is also worth noting that neither Shakespeare nor his contemporaries are all that squeamish about sex. No society in which men wear codpieces can be.

And so possibly one of the most interesting things that Sonnet 9 does is remind us that we in our society – I am talking quite specifically about Britain, Western Europe and North America in the third decade of the 21st century – are probably more prudish, more moralistic, more, ironically, worked up and sensitive about the earthy, fleshy, raunchy sexiness of sex than Shakespeare, his young man, and their contemporaries were. And indeed, as we are soon to find out, about sexuality. But that has not really come into play yet, and we want to go by what the words themselves tell us in these sonnets, both case-by case and cumulatively, and so talking about sexuality and gender at this point would be jumping the gun by several blows.

But one more thing seems to occur, and this – again – may or may not be based in fact: it is but an impression. It is nevertheless an impression and if it were to turn out to be correct it would be significant enough: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, seem to be getting more daring, more bold. Whether that's because I'm getting bored with my task or whether it is that I am getting to know the young man, we don't know, but there is one critical, crucial, categorically important word that we haven't even mentioned yet, and it features here for the first time in this sequence: love. "No love toward others in that bosom sits," I say, and this is the first time in this, the traditionally accepted, originally published sequence, that we get the word 'love'. Nine sonnets in, in the penultimate line.

Is this significant? Of course it is. If nothing else, the fact alone that it has taken the poet this long to introduce the concept of 'love' is telling. So far, we've had a "lovely April" in Sonnet 3, we've had the young man addressed as an "unthrifty loveliness" in Sonnet 4, and in Sonnet 5 he became, by an intriguing poetic device, "the lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell." But nobody has mentioned 'love' before. Marriage, yes. Making children? Yes. 'Using' your beauty? Yes. 'Wasting' your beauty? Absolutely. But LOVE?...

This is the first time we hear of it, and so of course we are entitled to ask the Tina Turner question: just what exactly has love got to do with it all? For the poet? For the young man? For the young man's potential wife and mother of his still, as yet, potential children?

This sonnet does not tell us. But we stand a fair chance of finding out more as we continue our journey...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!