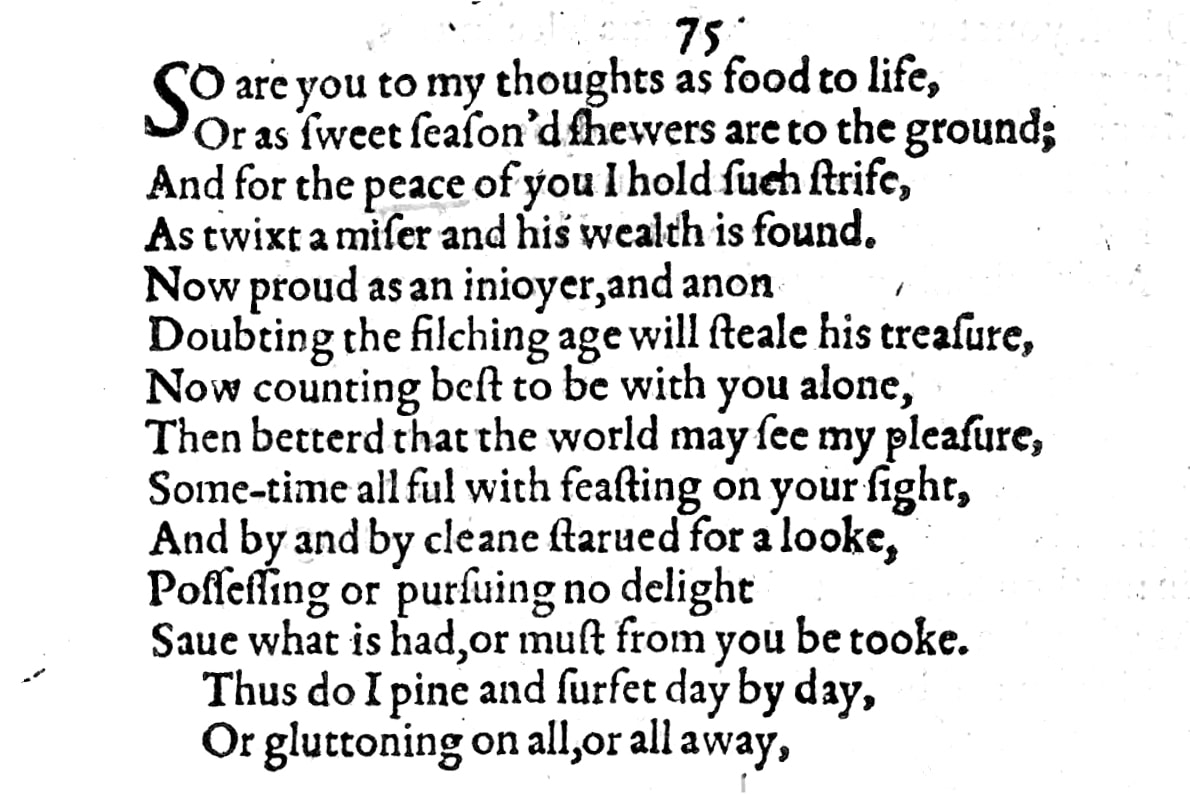

Sonnet 75: So Are You to My Thoughts as Food to Life

|

So are you to my thoughts as food to life,

Or as sweet seasoned showers are to the ground, And for the peace of you I hold such strife As twixt a miser and his wealth is found: Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure, Now counting best to be with you alone, Then bettered that the world may see my pleasure; Sometime all full with feasting on your sight, And by and by clean starved for a look, Possessing or pursuing no delight Save what is had or must from you be took. Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day, Or gluttoning on all, or all away. |

|

So are you to my thoughts as food to life,

Or as sweet seasoned showers are to the ground, |

You are to my thoughts as food is to life, or as sweetly fragrant showers are to the ground: in other words, you nourish me, you give me sustenance, I draw my strength from you.

The 'so' at the beginning of the line here is most likely self-contained for the simple meaning of 'such' or 'in the same way', and even though it is tempting to read into it a continuation from the previous few sonnets. It does not really suggest a direct link to Sonnet 74, which is, after all, paired with Sonnet 73. The 'sweet seasoned showers', meanwhile, allow for two slightly different but compatible readings: a) sweet, seasoned, to mean that they are both sweet, as in delightful, beautiful, pleasant to experience, and seasoned, meaning fragrant, as they would be in spring when the air carries the scent of the blossoming flowers, for example; and b) sweet-seasoned, meaning that the fragrance itself that they have is delightful, pleasant, again as one might find them to have in the spring. It is a very subtle difference. In addition to this we can also sense a probably intended allusion to the seasons with a third meaning of sweet-seasoned, to suggest that these showers are ones that happen in the delightful, pleasant season, which once more is of course spring or early summer. We can readily assume that Shakespeare is aware of all three and enjoys the layering of meanings as so very often he does. |

|

And for the peace of you I hold such strife

As twixt a miser and his wealth is found: |

And for the peace and contentment and pleasure that I get from having you as my lover, I experience the same internal struggle as can be found in a miser with his own wealth.

There is an obvious and satisfying juxtaposition of the peace afforded to Shakespeare by having the young man in his life and the strife – which by definition is a "bitter disagreement" or "conflict" (Oxford Languages) – that comes with it at the same time, and it may well here be deliberately placed to draw attention to the conflicted nature of the relationship: In Sonnet 35, immediately after the young man had his fling with Shakespeare's own mistress, Shakespeare told the young man: Such war and peace is in my love and hate That I an accessory needs must be To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me. And this here may similarly be hinting at a similar fundamental predicament, even though there is no suggestion that the young man is conducting a specific affair with somebody else right at this moment. |

|

Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon

Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure, |

And here is the elaboration on this conflicted relationship the miser has with his wealth and that I have with you: one moment he is proud as the person who can enjoy his good fortune and privilege, and the next he fears that the thieving times he lives in will invariably lead to someone stealing his treasure.

|

|

Now counting best to be with you alone

Then bettered that the world may see my pleasure, |

And note how here, mid-quatrain, Shakespeare switches from the miser to himself: one moment I consider it best to be with you alone – by implication so that I can enjoy your company undisturbed and don't run the risk of you being taken away from me – but the next moment I think it would be even better if the world could see both the 'object' of and the reason for my pleasure, namely you.

This is human nature, of course: we want the world to see how fortunate we are: when we have a boyfriend who is intelligent, handsome, and just roundly adorable, we want to show him to the world, we want to introduce him to our friends and say, here he is, this is my boyfriend! |

|

Sometime all full with feasting on your sight

And by and by clean starved for a look, |

Sometimes I am all replete with feasting on your sight, meaning I can get my full fill of looking at you because you are with me, and then, by and by, I am entirely starved for a look, obviously because you are absent.

John Kerrigan in the New Penguin edition ventures that 'look' here may also refer to a "desired glance from the friend, or a look exchanged," and it is entirely within the realms of possibilities that Shakespeare has this in mind too. This progression from being satiate to being starved happening 'by and by' entails a subtle acknowledgment that the sense of gratification I get from being with you and looking at you lasts for a while, but when you go away, as your absence stretches out over time, so my hunger for seeing you increases until I am 'clean starved'. 'Clean' here means 'completely', 'entirely', as we still use it in 'clean forgotten'. |

|

Possessing or pursuing no delight

Save what is had or must from you be took. |

And then at that time, when I am clean starved for a look, I neither possess nor am I able to pursue any delight other than the delight that can be had from you or must be taken from you.

Two fascinating facets here to these two lines: Firstly, the introduction of the verb 'possess' which does imply a sense or degree of 'ownership' and the pairing of this with the pursuit of that same delight, meaning that even when I don't have you and don't have you near me, I am so possessed, even obsessed with you that I cannot pursue any other pleasures, be they now contained in things or activities or persons. And secondly, the subtle but unmistakable hint that not everything that I have of you or wish to have of you comes to me by your voluntary generous gift, there are occasions when I must take it myself. This tallies well with our impression of the young lover as being nowhere near as forthcoming in his displays and gestures of affection to Shakespeare as Shakespeare is in his to the young man. |

|

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day,

Or gluttoning on all, or all away. |

In this way do I pine – starve, long for, yearn for you – one day and the next day I surfeit on you, meaning I "consume too much" (Oxford Languages) of you. This latter hardly seems possible in view of how great the desire is for the young man, but it is telling that Shakespeare here employs a word that has a strong implication of excess, planting in us – and be it but subconsciously – the question: can there in fact and indeed be too much of a good thing?

This sense of abundance to excess is reinforced in the last line: I am either gluttoning on everything that I have, which is you, or everything that I have is away from me and I am left with nothing. |

Sonnet 75 marks a moment of comparative calm in the turbulent relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover.

With its sober assessment of a continuously conflicted world of emotions that oscillate between abundant joy at being allowed to bask in the presence of the young man and utter dejection at missing him when he is absent, the sonnet seems to reconcile its poet with the reality of loving a person who is, in matters of the heart and most likely others too, a law unto himself.

Following, as it does, a set of four related and internally strongly linked pairs which themselves form part of a coherent sequence that meditated on the profound themes of age and death, the passing of time and the ultimately impending end to any thing that exists under the sun, and in contrast to the plaintive tone of several of the sonnets we encountered earlier, Sonnet 75 simply states matters as they are and appears to be content to leave it at that. And in doing so, it allows us to take stock of the situation and not so much discover new facts as confirm one or two observations that we have felt we were able to make along the way.

In the magnificent 1999 film Fight Club, based on the novel with the same title by Chuck Palahniuk, Tyler Durden, so memorably inhabited by Brad Pitt, at one point turns around to the unnamed narrator and principal protagonist of the story, played by Edward Norton, and urges him to realise that "the things you own end up owning you." The line is usually credited to the author who is also one of the screenwriters, though the insight, it is fair to say, is one that reaches back thousands of years.

Sonnet 75, in its portrayal of the miser as a rich person who with his wealth possesses a great treasure, but who is trapped by his fear of losing it, who wants to protect it not only from the many potential robbers, thieves, and swindlers, but also from the prying eyes of the envious so as to be able to enjoy it undisturbed, but who at the same time feels the urge to shout his joy from the rooftops and put his great fortune on display for all the world to see, brings back to mind this fundamental paradox: if we think we own something, it owns us quite as much. And if that 'thing' is not an inanimate object or a material valuable or some wealth, but a person, with all their own emotions, connections, priorities, interests, foibles, flaws, surprises, and innate complexities, then that 'possession' becomes a kaleidoscope of ever shifting constellations.

Mostly with longer term relationships, we try to stabilise this by formalising them – through marriage, civili partnership, a public or private commitment to monogamy, or a mutual understanding of boundaries and rules of play – to give us some sense of belonging in there, belonging together, even if we understand that it is impossible to belong to someone entirely or they entirely to us. And what Sonnet 75 makes almost explicit is that for William Shakespeare this stability, such a more formal commitment, even if it were made in private, is not forthcoming. After all this time that I have loved you and that we have been together even though of course at times we have been apart, I still have no kind of certainty. I love you, but I cannot trust you not to abandon me. I relish your company, but then you disappear for days, maybe weeks, on end and I don't know where you are or what you are up to, and the same is true when I go away for whatever reason, and when you're away, I miss you so much that I cannot find joy elsewhere.

This person, whoever he is, has Shakespeare at his feet, or eating out of the palm of his hand. Or at his beck and call. Much as we have been getting the impression across many of these sonnets – Sonnets 26, 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 48, 57 & 58, and 61 all speak to this to varying degrees – what we are witnessing is not a balanced relationship of equals. Not only is there the age difference, of which similarly there can be no doubt – Sonnets 22, 41, and 73, spread right across the collection, all mention it – there is also the obvious discrepancy in status and position, references to which we find directly or indirectly in at least six of the first 17 Procreation Sonnets and then also in Sonnets 26, 36, 37, 38, 69 & 70, and 71 & 72.

Sonnet 75, in its apparently unspectacular way sums them all up. If, around now, very near the midpoint of the collection and just about two thirds into the relationship with the young man we were looking for a sonnet that encapsulates the nature of this relationship, here Shakespeare delivers: this is exactly what it is:

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day

Or gluttoning on all, or all away.

The fact alone that I can call you my lover bestows upon me an abundance beyond my own imagination. But the all that I have is also nothing. Because you are not mine and and I am not yours and we both know nothing can change that, because even if you wanted to – which not for one moment I may suggest you do – you could never be the kind of man who is mine alone, and I couldn't be yours alone, and the irony of it all is that if we were just the two of us in this relationship, both on the same page, in the same boat, moving in the same direction at the same time, with no-one and nothing else on the outside world infringing upon it, then the magic of this maddening love would evaporate in a flash.

But what of the caveat – we need to bring this in every so often since it has every so often been raised – that this may not be one relationship? What if the contention, brought by some scholars, is correct that these sonnets just cited are not all addressed to or written about the same young man, but to and about a whole range of different young men and possibly also young women? I mentioned in the last episode that I hold not much store with that and I gave there, as I have given throughout the series so far, some of my reasons for rejecting that idea as improbable to the point of being implausible so as not to say impossible. Do we have proof of that being the case in the fact alone that all these sonnets seem to coalesce into the profile of a young lover with certain clearly identifiable characteristics and a relationship he conducts with Shakespeare that fits this character perfectly? We do not. The possibility – albeit to my mind only now in brittle theory – still exists that this is not one lover but several, even many.

What will put paid to this notion and disabuse us of it in a way that is virtually impossible to dismiss, is Sonnet 76: on the surface one of the least spectacular, so as not to say meekest, of them all, it turns out to be, in this regard alone, one of the most dependably revealing...

With its sober assessment of a continuously conflicted world of emotions that oscillate between abundant joy at being allowed to bask in the presence of the young man and utter dejection at missing him when he is absent, the sonnet seems to reconcile its poet with the reality of loving a person who is, in matters of the heart and most likely others too, a law unto himself.

Following, as it does, a set of four related and internally strongly linked pairs which themselves form part of a coherent sequence that meditated on the profound themes of age and death, the passing of time and the ultimately impending end to any thing that exists under the sun, and in contrast to the plaintive tone of several of the sonnets we encountered earlier, Sonnet 75 simply states matters as they are and appears to be content to leave it at that. And in doing so, it allows us to take stock of the situation and not so much discover new facts as confirm one or two observations that we have felt we were able to make along the way.

In the magnificent 1999 film Fight Club, based on the novel with the same title by Chuck Palahniuk, Tyler Durden, so memorably inhabited by Brad Pitt, at one point turns around to the unnamed narrator and principal protagonist of the story, played by Edward Norton, and urges him to realise that "the things you own end up owning you." The line is usually credited to the author who is also one of the screenwriters, though the insight, it is fair to say, is one that reaches back thousands of years.

Sonnet 75, in its portrayal of the miser as a rich person who with his wealth possesses a great treasure, but who is trapped by his fear of losing it, who wants to protect it not only from the many potential robbers, thieves, and swindlers, but also from the prying eyes of the envious so as to be able to enjoy it undisturbed, but who at the same time feels the urge to shout his joy from the rooftops and put his great fortune on display for all the world to see, brings back to mind this fundamental paradox: if we think we own something, it owns us quite as much. And if that 'thing' is not an inanimate object or a material valuable or some wealth, but a person, with all their own emotions, connections, priorities, interests, foibles, flaws, surprises, and innate complexities, then that 'possession' becomes a kaleidoscope of ever shifting constellations.

Mostly with longer term relationships, we try to stabilise this by formalising them – through marriage, civili partnership, a public or private commitment to monogamy, or a mutual understanding of boundaries and rules of play – to give us some sense of belonging in there, belonging together, even if we understand that it is impossible to belong to someone entirely or they entirely to us. And what Sonnet 75 makes almost explicit is that for William Shakespeare this stability, such a more formal commitment, even if it were made in private, is not forthcoming. After all this time that I have loved you and that we have been together even though of course at times we have been apart, I still have no kind of certainty. I love you, but I cannot trust you not to abandon me. I relish your company, but then you disappear for days, maybe weeks, on end and I don't know where you are or what you are up to, and the same is true when I go away for whatever reason, and when you're away, I miss you so much that I cannot find joy elsewhere.

This person, whoever he is, has Shakespeare at his feet, or eating out of the palm of his hand. Or at his beck and call. Much as we have been getting the impression across many of these sonnets – Sonnets 26, 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 48, 57 & 58, and 61 all speak to this to varying degrees – what we are witnessing is not a balanced relationship of equals. Not only is there the age difference, of which similarly there can be no doubt – Sonnets 22, 41, and 73, spread right across the collection, all mention it – there is also the obvious discrepancy in status and position, references to which we find directly or indirectly in at least six of the first 17 Procreation Sonnets and then also in Sonnets 26, 36, 37, 38, 69 & 70, and 71 & 72.

Sonnet 75, in its apparently unspectacular way sums them all up. If, around now, very near the midpoint of the collection and just about two thirds into the relationship with the young man we were looking for a sonnet that encapsulates the nature of this relationship, here Shakespeare delivers: this is exactly what it is:

Thus do I pine and surfeit day by day

Or gluttoning on all, or all away.

The fact alone that I can call you my lover bestows upon me an abundance beyond my own imagination. But the all that I have is also nothing. Because you are not mine and and I am not yours and we both know nothing can change that, because even if you wanted to – which not for one moment I may suggest you do – you could never be the kind of man who is mine alone, and I couldn't be yours alone, and the irony of it all is that if we were just the two of us in this relationship, both on the same page, in the same boat, moving in the same direction at the same time, with no-one and nothing else on the outside world infringing upon it, then the magic of this maddening love would evaporate in a flash.

But what of the caveat – we need to bring this in every so often since it has every so often been raised – that this may not be one relationship? What if the contention, brought by some scholars, is correct that these sonnets just cited are not all addressed to or written about the same young man, but to and about a whole range of different young men and possibly also young women? I mentioned in the last episode that I hold not much store with that and I gave there, as I have given throughout the series so far, some of my reasons for rejecting that idea as improbable to the point of being implausible so as not to say impossible. Do we have proof of that being the case in the fact alone that all these sonnets seem to coalesce into the profile of a young lover with certain clearly identifiable characteristics and a relationship he conducts with Shakespeare that fits this character perfectly? We do not. The possibility – albeit to my mind only now in brittle theory – still exists that this is not one lover but several, even many.

What will put paid to this notion and disabuse us of it in a way that is virtually impossible to dismiss, is Sonnet 76: on the surface one of the least spectacular, so as not to say meekest, of them all, it turns out to be, in this regard alone, one of the most dependably revealing...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!