Sonnet 85: My Tongue-Tied Muse in Manners Holds Her Still

|

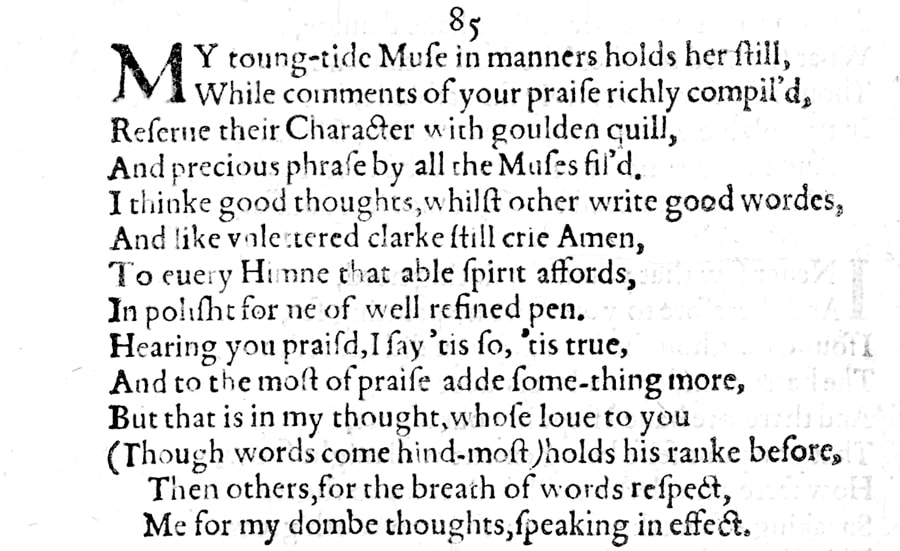

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still,

While comments of your praise, richly compiled, Reserve their character with golden quill And precious phrase by all the Muses filed. I think good thoughts, whilst other write good words, And like unlettered clerk still cry 'amen!' To every hymn that able spirit affords In polished form of well-refined pen. Hearing you praised, I say, ''tis so, 'tis true', And to the most of praise add something more, But that is in my thought, whose love to you, Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before. Then others for the breath of words respect, Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect. |

|

My tongue-tied Muse in manners holds her still,

|

The poem further develops the argument from Sonnets 82, 83, and 84, now elaborating on Shakespeare's reasons for staying silent about the young man's exquisite qualities:

My Muse, for which in this instance read not so much my source of inspiration as my poetic voice, remains quiet in accordance with good manners or polite conduct, in other words it does not boast or make declamations about your great worth so as not to fall foul of social decorum... The 'still' can be read in two ways, and as almost always, we may assume that this is intentional: firstly, as 'quiet', 'silent', as just applied, but secondly also as 'always', and 'ongoing', in the sense of: my Muse continues to hold on to good manners, in contrast, as is then implied, to these other poets' Muses which engage in an unseemly match jostling for attention. |

|

While comments of your praise, richly compiled,

Reserve their character with golden quill And precious phrase by all the Muses filed. |

...and it does so while treatises of your praise, meaning pieces of writing that praise you and speak of your worth and that are being written for you in elaborate, rich, flowery language, are stored and thus preserved with a gilded pen, meaning a precious, aureate style and phrasing, polished and refined by all the other Muses, here meaning the other poets.

The Quarto Edition's 'their' in "Reserve their character with golden quill" is often emended to 'thy', and you will find editors cogently argue both the case for and against this emendation. With it, the line reads "Reserve thy character with golden quill" and what speaks for this is that we are of course talking about the 'storing' or 'reserving' or even 'preserving' of the young man's person in eulogistic, preciously phrased, golden language. Also, as we have seen frequently before, 'thy' and 'their' routinely get mixed up by the typesetters of this collection and so it would not be in the least surprising for this to have happened here. What speaks against the emendation are the following points: 1) It is not necessary. The sentence makes perfect sense as it is, and if in doubt, as you know I believe we should err on the side of caution when it comes to 'correcting' or 'improving' any writer's work, let alone that of the most important and widely acknowledged to be greatest poet of the English language. The sentence works perfectly as it stands with 'character' meaning "the style of writing peculiar to any individual" as one of the valid definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary has it. 2) This entire quatrain is not primarily about the young man but about writing about the young man. Yes, the sentence also makes sense if we read it as making this explicit by stating that the writing 'reserves' your character – as in preserves your personality, your essence – much in the way Sonnet 84 suggested that any writing should. Even this though rather favours 'their' as a more elegant turn of phrase, because the 'comments of your praise' can then do both, preserve their gilded writing style, which is doubtlessly what these poets would seek to do, and store for posterity also the character they concern themselves with, which is therefore 'their' character, as in the central character of their writing, namely you. 3) If we allow for 'thy character' then we have Shakespeare mixing 'you'/'your'/'yours' with 'thou'/'thy'/'thine' in the same poem, which is not unheard of but very rare. So rare, in fact, that we can count the number of times this occurs in the entire collection of sonnets on one finger: it happens in Sonnet 24, and only there. Sonnet 24 is one of the most complex and psychologically intricate sonnets of them all and while we don't know why Shakespeare mixes the forms there, he seems to be doing so deliberately and pointedly and in a context where his internal conflict arising from the difference in status between him and his young lover and also between the level of emotional investment that his young lover has compared to his own is being actively, consciously thematised. And so for Shakespeare to do this here casually in a slapdash manner when neither sense nor prosody require it seems extremely unlikely. And as you know, because I have said so many times: in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend... And so for these reasons, I have retained the original 'their' and refrained from adopting the widely, but by no means universally, preferred emendation to 'thy'. One more thing: you may come across is the idea that "by all the Muses filed" may mean that all the nine Muses – the goddesses of the arts – have polished this precious phrase. I usually also refrain from dismissing other people's interpretation, since interpretation is obviously just that, someone's understanding of something that lies before them, but in this instance I really need to caution against it. The classical Muses inspire and embody the arts and sciences, as categorised in antiquity, and while three of them could possibly – some at something of a stretch – be imagined to take their influence on poetic praise, such as a sonnet or an encomium, six of them really couldn't. The nine Muses are, in case you are interested: - Calliope (epic poetry) - Clio (history) - Polyhymnia (mime) - Euterpe (flute) - Terpsichore (light verse and dance) - Erato (lyric choral poetry) - Melpomene (tragedy) - Thalia (comedy, she is also a Charite, or what the Romans then refer to as the three Graces) - Urania (astronomy) And so as you can see, Calliope with epic poetry, Terpsichore with light verse and dance, and Erato with lyric choral poetry could all potentially be imagined to get involved in the polishing and refining of a piece of poetry; the others wouldn't really deign to do so, one would have thought. So 'Muse' here, as elsewhere in these sonnets, for example Sonnet 21 – "So is it not with me as with that Muse | Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse," clearly refers to the rival poet himself, even though he is here again, as he was in Sonnet 83, generalised into a generic plural. |

|

I think good thoughts, whilst other write good words,

|

I think good thoughts, while others write good words,

'Other' as a form of the plural 'others' is common in Elizabethan English. |

|

And like unlettered clerk still cry 'amen!'

To every hymn that able spirit affords In polished form of well-refined pen. |

...and like an untutored or uneducated and therefore lowly and himself incapable clerk, I always and forever in agreement say 'amen!' to every hymn or eulogy that a skilled or capable poet can come up with in the polished form of a refined, well-developed, what we might today call sophisticated, style.

This directly relates back to the sentiments expressed in Sonnet 78 which started this whole preoccupation with the rival poet: Thine eyes that taught the dumb on high to sing And heavy ignorance aloft to fly Have added feathers to the learned's wing And given grace a double majesty. Here too Shakespeare presents himself as the supposedly 'ignorant', 'unlettered' outsider who cannot hold his own against the 'learned', 'able' spirit of his rival. Note here that 'spirit' is pronounced as one syllable: sp'rit. 'Amen' itself – which we are familiar with from all three Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – when translated from Hebrew into English is usually rendered as: 'truly', or 'verily', or 'it is so', and as if to make sure everybody gets this, Shakespeare now doubles down on it: |

|

Hearing you praised I say, ''tis so, 'tis true',

And to the most of praise add something more, |

Hearing you praised – in these poems that other poets write to you – I say, 'it is so, it is true', and to the highest praise even add something more, something, as is implied, of more importance, therefore constituting a higher praise...

|

|

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before. |

...but I don't say this out loud or write it down, this additional, even higher praise that I have for you I hold in my thought, and my thought is so informed and guided by and filled with love for you that even though any words that I might be able to find come last in the ranking of poets' output and therefore have to march at the rear of a metaphorical procession, it actually holds its place before and therefore in front and above everything else.

In other words: when I think my good thoughts and others write their good words, then because my love for you is so genuine and so strong, the thoughts that I think for you and hold in my heart are of a far greater quality than any of these words that other poets are able to produce. Seeing Shakespeare associate 'thought' with 'love' is something we are used to by now. You may perhaps recall that relatively recently, with Sonnet 69, we briefly discussed the Elizabethan belief that thought resided in the heart as much as in the brain, and was therefore much more closely related to emotion than we would understand it today, where we effectively separate thought from feelings almost as opposites. |

|

Then others for the breath of words respect,

Me for my dumb thoughts, speaking in effect. |

And so therefore do respect others – implied of course is other poets, specifically this one other poet – for the breath of their words, but respect me for my silent thoughts which speak through what I do and am, my action, my practice, my whole being.

Invoking 'breath' with 'words' here brings to our minds the notion of 'air', even 'hot air', an insubstantial, flighty quality that comes and goes. We today still say of someone who is all talk and no action that they are 'full of hot air'. And of course we also still say that 'actions speak louder than words'. This may be a somewhat surprising assertion for a poet to make, but very clearly, and quite beyond doubt, Shakespeare here positions his authentic, albeit muted, because tongue-tied, love as of much greater substance and value than anything his rival has to offer. It is noteworthy perhaps that this more dismissive use of 'breath' does seem to stand in considerable contrast to Sonnet 81 where the breath of people who speak Shakespeare's own poetry becomes the very element that brings the young man to life for all posterity: You still shall live, such virtue hath my pen, Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men. And what, if anything, we should make of this, I cannot say. 'Dumb' again, as in Sonnet 83, means 'mute', not 'stupid'. |

With Sonnet 85, William Shakespeare concludes the group-within-a-group of four sonnets that concern themselves with his own defence against the charge – evidently levied by his young lover – that his poetry is lacking in lavish expressions of praise and that 'imputes', as Shakespeare himself calls it in Sonnet 83, his silence, or, as it should more accurately be described, comparative silence, as a sin. Here, Shakespeare rounds off his main argument, giving as the reason for this 'silence' simply decorum – good manners – and suggesting that while he can agree with all the praise heaped on the young man by other poets – for which here again we can assume he means principally one other poet – discretion demands that he remain silent and allow for his actions to express his genuine love for him better than words.

Every so often in the course of our deliberations and reflections on these sonnets by William Shakespeare, we have to concede that we know very little. We don't know who this rival poet is, we don't know who the young man is, at least not for certain. We don't know with absolute certainty when each poem was written, and we can't be sure that it was received, heard, or read by its recipient. We don't know, for the most part, what the recipient did or said in response.

And every so often a window opens upon an insight that is really quite remarkable. We know for certain that at one point there was a crisis during which the young man had a fling or an affair with Shakespeare's own mistress: Sonnets 33 to 35 and 40 to 42 couldn't be clearer about this. We now for certain that there are periods during which Shakespeare is away from his young lover, where he misses him, unsure of how far he can trust him. Sonnets 48, 50 & 51 make this extraordinarily clear. And we can say without a doubt that Shakespeare is acutely aware of the fact that he is older than this young man and that while their love may and should be everlasting, their relationship, such as it is, simply can't. The most profoundly beautiful expression of which comes in Sonnets 73 & 74.

The entire Rival Poet sequence also leaves us in no doubt that there is another poet who infringes on Shakespeare's territory, both professionally and emotionally. What we may at times feel we don't know is why this is such a big deal for Shakespeare. Shouldn't a writer as brilliant, as inventive, as confident with words as he be able to effectively brush this off and say to himself, of course a young man like this will have other people vying for his attention and even seek his patronage, but hey, so be it, I need not worry about this because with words, I can do anything: I can transport you to Italy for the greatest love story ever told, I can show you the battlefields of England and France, and I can conjure up a magical forest on the outskirts of Athens: I can shock, charm, and enchant. So why, having written enough sonnets by now to this one young man to be able to tell him, in Sonnet 76, "O know, sweet love, I always write of you?" does he suddenly get tongue-tied and – being the person who like no other will have shaped the English language and who will by the end of his life have left us with just shy of a million words – end up agreeing with Ronan Keating of all people who, in the song by Paul Overstreet and Don Schlitz reckons that sometimes it is just the case that "you say your best when you say nothing at all."

Sonnet 85 doesn't answer this question. But what Sonnet 85 does is prepare the ground for Sonnet 86. And in the light of Sonnet 85 Sonnet 86 will pretty much settle the matter, as we shall see. Because Sonnet 85 introduces into the equation a concept and a concern that features only thrice in these sonnets: manners.

The last time we came across them was in Sonnet 39:

O how thy worth with manners may I sing

When thou art all the better part of me?

What can mine own praise to mine own self bring,

And what is't but mine own when I praise thee?

And there it wasn't particularly laden with meaning or subtext, it was a straightforward-enough rhetorical question: good manners forbid that I praise myself – an element of etiquette we may in parts have forgotten in our age of self-promotion and life-curation – and so seeing that you are the better part of me, if I praise you then I end up praising myself, which is bad manners.

Manners matter to Shakespeare. While they will only come up once more in the sonnets, throughout his complete works they are mentioned no fewer than a further 73 times. And when we get to Sonnet 111 we shall see that "public manners," as he specifically calls them there, for Shakespeare strongly relate to status, public perception, and therefore standing in society. Shakespeare is the man, after all, who in the late 1590s, so in all likelihood about five to six years after these sonnets are written, will endeavour to get a coat of arms for his family: a symbol of heraldry and therefore of established, recognised and recognisable social status.

And so, following all his deliberations about how the young man does not need to be praised beyond his actual, natural beauty and unimpeachable character, and how in any case words cannot surpass him, and even how he, the young man, diminishes himself in being so keen on praise, it may seem a tad perplexing to find William Shakespeare open this sonnet with 'manners'. Because what, we are entitled to ask, have manners got to do with it? Can it really be considered such bad manners to eulogise a beautiful young person excessively. Well, yes, a bit. In the sense of being perhaps somewhat ill-judged and unrefined and therefore not in the very best of subtle taste. But not to the point where it would tarnish your general public reputation. Especially not if that's the current fashion that other, apparently respected and admired poets adhere to. It may go against your grain and feel like cheapening your own style, and clearly for Shakespeare it does, we remind ourselves once more of Sonnet 21 where he categorically states "Let them say more that like of hearsay well | I will not praise that purpose not to sell." So not succumbing to the mode in demand for reasons of personal authenticity and artistic integrity: absolutely, we can see and buy that at once. But for reasons of manners? That doesn't ring entirely true.

Unless, of course, there is more to it all than meets the eye. And clearly there is. William Shakespeare himself effectively says as much:

Hearing you praised, I say, ''tis so, 'tis true',

And to the most of praise add something more,

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

Because what exactly is it that in Elizabethan England and for quite some time thereafter – some would argue in certain circumstances even today – you can't, with good manners, talk about? Your admiration for someone? Hardly. Your affection? Your love? No, these can be coached in words that are entirely acceptable. An intimate, close, physical relationship? Absolutely not. You can have that, but you can't talk about it, not in Shakespeare's England. You can pun on it, reference it, joke about it, even insult somebody with it, but you cannot openly, frankly, seriously and sincerely talk about sex. Especially not between men. Most especially not between two men of whom one is a young, supremely well-connected establishment figure and the other an increasingly visible, audible, and therefore recognisable playwright and poet. And if that were not enough to make manners a meaningful consideration in matters, then the arrival on the scene of another poet, who is yet another known figure, and another man, most certainly does.

Am I about to get to the point? Indeed I am. But not until the next episode, when we discuss Sonnet 86, the final one in this Rival Poet sequence of sonnets, because that's where our poet gets to the point. And there, bearing everything in mind that we know and have said so far, he then suddenly makes perfect sense...

Every so often in the course of our deliberations and reflections on these sonnets by William Shakespeare, we have to concede that we know very little. We don't know who this rival poet is, we don't know who the young man is, at least not for certain. We don't know with absolute certainty when each poem was written, and we can't be sure that it was received, heard, or read by its recipient. We don't know, for the most part, what the recipient did or said in response.

And every so often a window opens upon an insight that is really quite remarkable. We know for certain that at one point there was a crisis during which the young man had a fling or an affair with Shakespeare's own mistress: Sonnets 33 to 35 and 40 to 42 couldn't be clearer about this. We now for certain that there are periods during which Shakespeare is away from his young lover, where he misses him, unsure of how far he can trust him. Sonnets 48, 50 & 51 make this extraordinarily clear. And we can say without a doubt that Shakespeare is acutely aware of the fact that he is older than this young man and that while their love may and should be everlasting, their relationship, such as it is, simply can't. The most profoundly beautiful expression of which comes in Sonnets 73 & 74.

The entire Rival Poet sequence also leaves us in no doubt that there is another poet who infringes on Shakespeare's territory, both professionally and emotionally. What we may at times feel we don't know is why this is such a big deal for Shakespeare. Shouldn't a writer as brilliant, as inventive, as confident with words as he be able to effectively brush this off and say to himself, of course a young man like this will have other people vying for his attention and even seek his patronage, but hey, so be it, I need not worry about this because with words, I can do anything: I can transport you to Italy for the greatest love story ever told, I can show you the battlefields of England and France, and I can conjure up a magical forest on the outskirts of Athens: I can shock, charm, and enchant. So why, having written enough sonnets by now to this one young man to be able to tell him, in Sonnet 76, "O know, sweet love, I always write of you?" does he suddenly get tongue-tied and – being the person who like no other will have shaped the English language and who will by the end of his life have left us with just shy of a million words – end up agreeing with Ronan Keating of all people who, in the song by Paul Overstreet and Don Schlitz reckons that sometimes it is just the case that "you say your best when you say nothing at all."

Sonnet 85 doesn't answer this question. But what Sonnet 85 does is prepare the ground for Sonnet 86. And in the light of Sonnet 85 Sonnet 86 will pretty much settle the matter, as we shall see. Because Sonnet 85 introduces into the equation a concept and a concern that features only thrice in these sonnets: manners.

The last time we came across them was in Sonnet 39:

O how thy worth with manners may I sing

When thou art all the better part of me?

What can mine own praise to mine own self bring,

And what is't but mine own when I praise thee?

And there it wasn't particularly laden with meaning or subtext, it was a straightforward-enough rhetorical question: good manners forbid that I praise myself – an element of etiquette we may in parts have forgotten in our age of self-promotion and life-curation – and so seeing that you are the better part of me, if I praise you then I end up praising myself, which is bad manners.

Manners matter to Shakespeare. While they will only come up once more in the sonnets, throughout his complete works they are mentioned no fewer than a further 73 times. And when we get to Sonnet 111 we shall see that "public manners," as he specifically calls them there, for Shakespeare strongly relate to status, public perception, and therefore standing in society. Shakespeare is the man, after all, who in the late 1590s, so in all likelihood about five to six years after these sonnets are written, will endeavour to get a coat of arms for his family: a symbol of heraldry and therefore of established, recognised and recognisable social status.

And so, following all his deliberations about how the young man does not need to be praised beyond his actual, natural beauty and unimpeachable character, and how in any case words cannot surpass him, and even how he, the young man, diminishes himself in being so keen on praise, it may seem a tad perplexing to find William Shakespeare open this sonnet with 'manners'. Because what, we are entitled to ask, have manners got to do with it? Can it really be considered such bad manners to eulogise a beautiful young person excessively. Well, yes, a bit. In the sense of being perhaps somewhat ill-judged and unrefined and therefore not in the very best of subtle taste. But not to the point where it would tarnish your general public reputation. Especially not if that's the current fashion that other, apparently respected and admired poets adhere to. It may go against your grain and feel like cheapening your own style, and clearly for Shakespeare it does, we remind ourselves once more of Sonnet 21 where he categorically states "Let them say more that like of hearsay well | I will not praise that purpose not to sell." So not succumbing to the mode in demand for reasons of personal authenticity and artistic integrity: absolutely, we can see and buy that at once. But for reasons of manners? That doesn't ring entirely true.

Unless, of course, there is more to it all than meets the eye. And clearly there is. William Shakespeare himself effectively says as much:

Hearing you praised, I say, ''tis so, 'tis true',

And to the most of praise add something more,

But that is in my thought, whose love to you,

Though words come hindmost, holds his rank before.

Because what exactly is it that in Elizabethan England and for quite some time thereafter – some would argue in certain circumstances even today – you can't, with good manners, talk about? Your admiration for someone? Hardly. Your affection? Your love? No, these can be coached in words that are entirely acceptable. An intimate, close, physical relationship? Absolutely not. You can have that, but you can't talk about it, not in Shakespeare's England. You can pun on it, reference it, joke about it, even insult somebody with it, but you cannot openly, frankly, seriously and sincerely talk about sex. Especially not between men. Most especially not between two men of whom one is a young, supremely well-connected establishment figure and the other an increasingly visible, audible, and therefore recognisable playwright and poet. And if that were not enough to make manners a meaningful consideration in matters, then the arrival on the scene of another poet, who is yet another known figure, and another man, most certainly does.

Am I about to get to the point? Indeed I am. But not until the next episode, when we discuss Sonnet 86, the final one in this Rival Poet sequence of sonnets, because that's where our poet gets to the point. And there, bearing everything in mind that we know and have said so far, he then suddenly makes perfect sense...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!