Sonnet 50: How Heavy Do I Journey on the Way

|

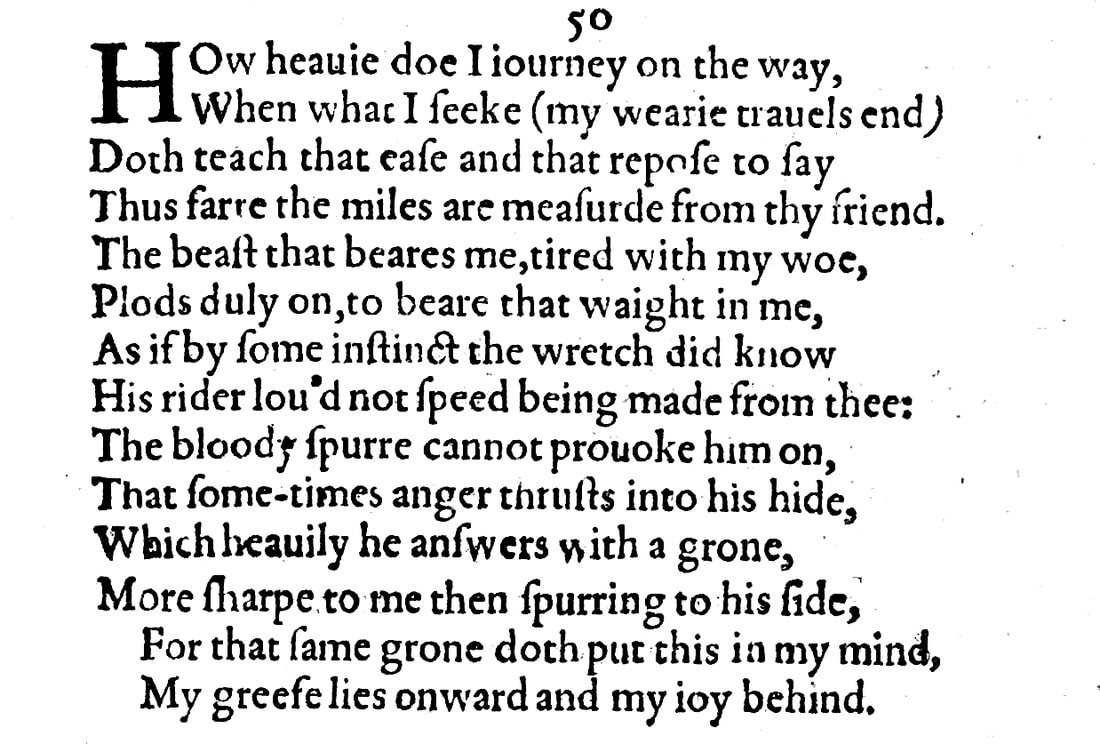

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel's end, Doth teach that ease and that repose to say: 'Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend'. The beast that bears me, tired with my woe, Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me, As if by some instinct the wretch did know His rider loved not speed being made from thee. The bloody spur cannot provoke him on That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide, Which heavily he answers with a groan, More sharp to me than spurring to his side, For that same groan doth put this in my mind: My grief lies onward, and my joy behind. |

|

How heavy do I journey on the way

When what I seek, my weary travel's end Doth teach that ease and that repose to say: 'Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend'. |

With how heavy a heart do I journey on my way, when what I am looking for, which is the end of my wearisome and tiring trip, only serves to remind me, when I can finally rest at my destination, of just how far I have come away from you.

We have noted before that travelling in Shakespeare's day is slow and cumbersome and exhausting. On a previous occasion, in Sonnet 27, we observed how the words travel and travail, meaning 'work', were being used interchangeably. This sonnet gives full expression to that experience, and the strain of a long ride on horseback is made worse by the fact that with every step the animal takes, I am moving further away from you. The phrasing "Doth teach that ease and that repose to say" is noteworthy, as it lends a voice to the rest and relaxation that awaits the traveller and lets these two abstract concepts speak to the poet and rider directly about his friend, the young man. |

|

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe

Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me |

The horse on which I, exhausted with my sorrow, ride, slowly and listlessly plods onwards, carrying me together with the burden of the weight I in turn carry on my shoulder...

To the physical tiredness from the actual journey comes the mental exhaustion that stems from the sadness of having to put more and more distance between myself and my young lover. The Quarto Edition here has 'duly', which would mean 'dutifully', or 'as instructed', or possibly even 'in a straight line in the right direction', as in 'due west' or 'due east', but even though this would also make sense, most editors emend to 'dully' which is a more obvious choice for a word that may quite easily have been either misspelt or simply spelt differently at the time. There is also the possibility – and it is in view of what we know about Shakespeare's use of language a strong one – that a deliberate pun is intended, deploying the word to mean both. |

|

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee. |

...as if by some instinct the unhappy animal knew that I, his rider, do not want to go fast as I move away from you.

The horse's wretchedness stems from the rider's unhappiness which, as a steady companion over long journeys like these he would be able to sense, and which he also gets to feel through the behaviour of the rider, as the next couple of lines make clear: |

|

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on

That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide, |

Even when my anger at his slow pace prompts me to spur him so hard that it draws blood, this does not make him go any faster.

The poet's frustration at having to be on this trip in the first place and at being obliged to make it to his destination at a reasonable hour makes him treat his horse badly, something he is acutely aware of, as indeed he seems to be of the pointlessness of doing so. |

|

Which heavily he answers with a groan

More sharp to me than spurring to his side, |

In response to the spur, he, the horse, groans heavily, and that groan is a sharper pain to me than it is to him...

|

|

For that same groan doth put this in my mind:

My grief lies onward and my joy behind. |

...because that same groan reminds me that what lies ahead of me is the grief and sorrow of being away from you, whereas the joy of being with you lies behind me.

|

Sonnets 50 & 51 once again come as a pair, whereby Sonnet 50 evokes in a measured tone of melancholy the sorrow and sadness Shakespeare senses on a strenuous journey at slowly having to move further and further away from his lover, while Sonnet 51 then contrasts this with a notion of just how eager he will be on his way back to him and how fast he wishes that return leg of the journey could happen.

As on previous occasions, we will look at both these sonnets back-to-back in the next episode, but concentrate on the first one of the pair, Sonnet 50, for now.

The sonnet offers a remarkably simple and straightforward insight into William Shakespeare's reality away from home, home here as always in the context of the sonnets referring to London, rather than to his family home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

We hear from the poet's pen directly and unambiguously that he is travelling on horseback – as opposed to, say, in a carriage – and we could scarcely hope for a more vivid characterisation of how this journey progresses through the English countryside: slowly, dully, ploddingly. The sonnet gives us no clues as to why Shakespeare is travelling or where he is going, other than that it is obviously a long and arduous trip that may very likely last all day long, or even stretch over several days. In Elizabethan England, on a good horse and along well-trodden routes you could travel between 30 to 40 miles a day, but on the kind of 'jade' Shakespeare describes – and as he calls him in the subsequent Sonnet 51 – it would likely be much less, probably in the region of 20 to 30 miles per day: not much more, then, than a good walker can cover over the same duration.

The sonnet makes no reference to the external hardships of travel, but this may be an opportune moment for us to bring them briefly back to mind: the condition of these roads was entirely weather-dependent and largely unreliable. A heavy downpour could not only drench you on your slow-moving beast, but also cause you to get stuck or place obstacles in your way: fallen branches, mud, and flooded tracks were all pretty much par for the cumbersome course. There were inns and pubs along the way, but for long stretches you would travel through open and largely empty country, which entailed not only a great deal of solitude – if you were on your own – and boredom, but also danger. Bandits, robbers, and thieves would routinely take advantage of those already so exposed to the elements, and with no satellite navigation and maps that were still in the relative infancy of cartography and therefore expensive, often incomplete, and in any case of only moderate reliability, you not only had to have your wits about you not to get ambushed, but also simply not to get lost.

When William Shakespeare here longs for his weary travel's end, much as when in Sonnet 27 he told us that "Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed," then this weariness in each case is not simply an ennui and generic lack of enthusiasm, but a deeply experienced tiredness that is compounded by the misery of being – and moving yet further – away from the person you want to be with.

One particularly interesting facet to the sonnet is that, similar to others which appear to belong to this extended period of absence, it makes no hint at Shakespeare being part of, or travelling in, a group. One of the possible and plausible theories that have been put forward, and that I also discussed on this podcast before, is that Shakespeare together with his theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, went touring when London theatres were closed for the plague. But none of the sonnets we have heard so far actually makes this altogether likely, let alone obvious. The voice we hear is one of a lone and lonely traveller. We have no proof of this, and it is entirely possible, of course, that Shakespeare is absolutely on the road with other people, but that he just isn't thinking of them and that they are effectively an irrelevance to his relationship with this young man, but considering how viscerally lived this sonnet in particular feels and sounds, one might quite reasonably expect any annoyance, aggravating element, or indeed relief or mitigating factor caused by a fellow traveller to find its way into the sonnet somehow.

Which leads me to speculate – and it is strictly a speculation this, and one here based not on words in the sonnet but on the absence of words in the sonnet – that Shakespeare is journeying on his own, perhaps to take on some work out of town, possibly as a teacher or tutor, for example.

The next poem in the sequence, Sonnet 51, will bring to a close not only the uncomplicated argument of this sonnet, but also the entire sequence of this time away that was established with Sonnet 43 and has been maintained ever since. With Sonnet 52, we get a joyous reunion and with it, a whole new impetus enters our poet's pen, bringing us some of possibly the most revelatory lines of verse about Shakespeare and his young lover that we have encountered thus far...

As on previous occasions, we will look at both these sonnets back-to-back in the next episode, but concentrate on the first one of the pair, Sonnet 50, for now.

The sonnet offers a remarkably simple and straightforward insight into William Shakespeare's reality away from home, home here as always in the context of the sonnets referring to London, rather than to his family home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

We hear from the poet's pen directly and unambiguously that he is travelling on horseback – as opposed to, say, in a carriage – and we could scarcely hope for a more vivid characterisation of how this journey progresses through the English countryside: slowly, dully, ploddingly. The sonnet gives us no clues as to why Shakespeare is travelling or where he is going, other than that it is obviously a long and arduous trip that may very likely last all day long, or even stretch over several days. In Elizabethan England, on a good horse and along well-trodden routes you could travel between 30 to 40 miles a day, but on the kind of 'jade' Shakespeare describes – and as he calls him in the subsequent Sonnet 51 – it would likely be much less, probably in the region of 20 to 30 miles per day: not much more, then, than a good walker can cover over the same duration.

The sonnet makes no reference to the external hardships of travel, but this may be an opportune moment for us to bring them briefly back to mind: the condition of these roads was entirely weather-dependent and largely unreliable. A heavy downpour could not only drench you on your slow-moving beast, but also cause you to get stuck or place obstacles in your way: fallen branches, mud, and flooded tracks were all pretty much par for the cumbersome course. There were inns and pubs along the way, but for long stretches you would travel through open and largely empty country, which entailed not only a great deal of solitude – if you were on your own – and boredom, but also danger. Bandits, robbers, and thieves would routinely take advantage of those already so exposed to the elements, and with no satellite navigation and maps that were still in the relative infancy of cartography and therefore expensive, often incomplete, and in any case of only moderate reliability, you not only had to have your wits about you not to get ambushed, but also simply not to get lost.

When William Shakespeare here longs for his weary travel's end, much as when in Sonnet 27 he told us that "Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed," then this weariness in each case is not simply an ennui and generic lack of enthusiasm, but a deeply experienced tiredness that is compounded by the misery of being – and moving yet further – away from the person you want to be with.

One particularly interesting facet to the sonnet is that, similar to others which appear to belong to this extended period of absence, it makes no hint at Shakespeare being part of, or travelling in, a group. One of the possible and plausible theories that have been put forward, and that I also discussed on this podcast before, is that Shakespeare together with his theatre company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, went touring when London theatres were closed for the plague. But none of the sonnets we have heard so far actually makes this altogether likely, let alone obvious. The voice we hear is one of a lone and lonely traveller. We have no proof of this, and it is entirely possible, of course, that Shakespeare is absolutely on the road with other people, but that he just isn't thinking of them and that they are effectively an irrelevance to his relationship with this young man, but considering how viscerally lived this sonnet in particular feels and sounds, one might quite reasonably expect any annoyance, aggravating element, or indeed relief or mitigating factor caused by a fellow traveller to find its way into the sonnet somehow.

Which leads me to speculate – and it is strictly a speculation this, and one here based not on words in the sonnet but on the absence of words in the sonnet – that Shakespeare is journeying on his own, perhaps to take on some work out of town, possibly as a teacher or tutor, for example.

The next poem in the sequence, Sonnet 51, will bring to a close not only the uncomplicated argument of this sonnet, but also the entire sequence of this time away that was established with Sonnet 43 and has been maintained ever since. With Sonnet 52, we get a joyous reunion and with it, a whole new impetus enters our poet's pen, bringing us some of possibly the most revelatory lines of verse about Shakespeare and his young lover that we have encountered thus far...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!