Sonnet 62: Sin of Self-Love Possesseth All Mine Eye

|

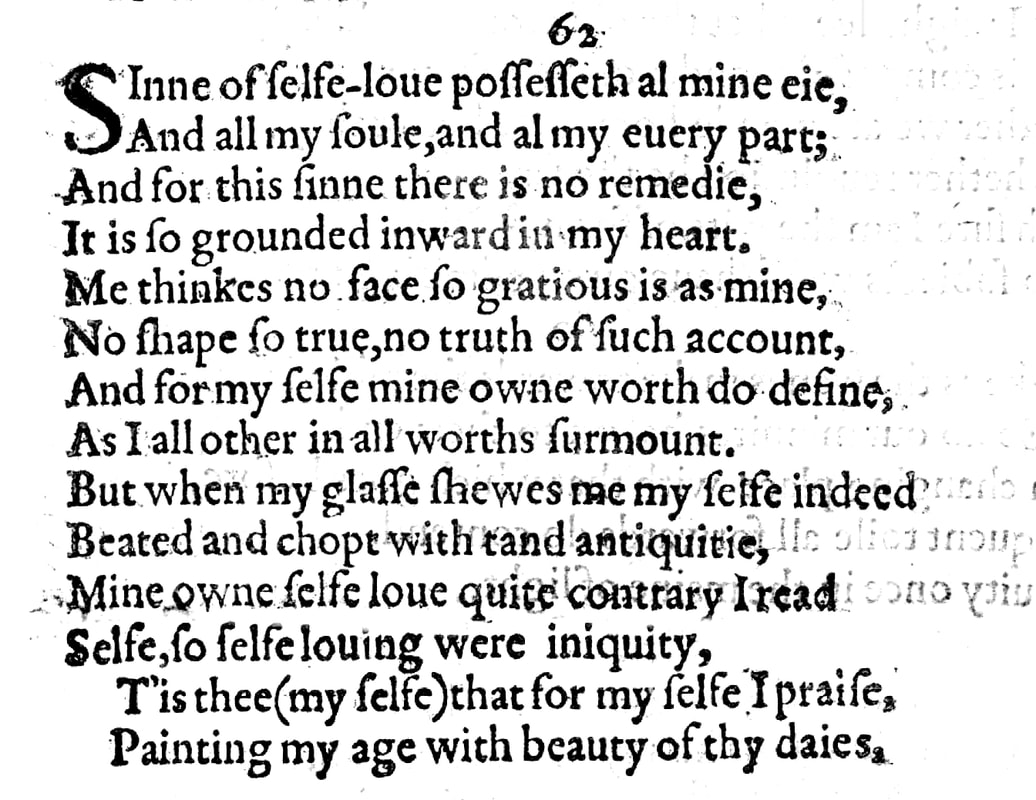

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part; And for this sin there is no remedy, It is so grounded inward in my heart. Methinks no face so gracious is as mine, No shape so true, no truth of such account, And for myself mine own worth do define As I all other in all worths surmount. But when my glass shows me my self indeed, Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity, Mine own self-love quite contrary I read: Self so self-loving were iniquity. Tis thee, my self, that for myself I praise, Painting my age with beauty of thy days. |

|

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye

And all my soul, and all my every part; |

Sin of self-love possesses my eye, my soul, my whole being.

Whitney Houston, in the song by Linda Creed and Michael Masser, may have felt that "learning to love yourself, it is the greatest love of all," but William Shakespeare here takes a more critical and sober view of himself, perceiving himself to be possessed by a reprehensible, conceited self-love, as he is about to describe, though not before noting the severity of this 'affliction'. |

|

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart: |

And for this sin there is no remedy or cure or, therefore, it being a sin, redemption, because it is so deeply rooted in my heart:

|

|

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account, |

I think that nobody's face is as gracious, for which here read graceful or beautiful, as mine, nobody's shape, meaning their figure, their body, so perfectly formed to the exact right standard of compositional balance, and no such standard of such high esteem or reputation as mine.

|

|

And for myself mine own worth do define

As I all other in all worths surmount. |

And I define my own worth in such terms that it surpasses the worth of all others.

This is really news to us: at no point in the entire series so far has Shakespeare ever given any indication that he thinks highly of himself in terms of his physicality, either his appearance or his stature, or that he considers himself to be particularly worthy. Up until now the only expressions of pride or self-belief have concerned his poetry, when predicting that it will outlast generations to keep the young man 'alive' in the minds of future readers, and even there he has had one or two serious lapses, such as in Sonnet 32, where he – albeit somewhat ironically, we ventured – referred to his verse as "these poor, rude lines." And as regards his sense of self-worth generally, he has, if anything downplayed this, most certainly in relation to the young man, as we saw most pointedly in the recent Sonnets 57 & 58, in which he refers to himself, perhaps also with some tongue in cheek, as the young lover's 'slave'. |

|

But when my glass shows me my self indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity, |

But when my mirror shows me my actual real self, beaten and chapped or scarred by my age, which is characterised by my leathery, wrinkled skin.

With this, one of my favourite lines in the entire canon, Shakespeare evokes the image of a wizened old man whose skin bears the wear and tear of an active life. Shakespeare's father was a glover, and frequently in Shakespeare's plays we find references to glove-making and leather processing techniques, and the 'tanned' here refers not to a suntan obtained by lounging out in the sun or on a sun bed – the idea of darkening and aging your skin deliberately by exposing it to the sun would have been preposterous to Elizabethans who prized a fair, untarnished, soft skin above all – but to the practice of tanning leather to turn the hide, from which it is made, into a durable and tough material. Shakespeare here – as he does occasionally – applies the adjective, in this case 'tanned', not to himself or to his skin, but to the 'antiquity' or age which bere causes the tanning. We came across something very similar as recently as the previous sonnet, Sonnet 61, where he opened with the lines: Is it thy will thy image should keep open My heavy eyelids to the weary night? Where of course it is not the night that is weary, but the poet, who is wearied by the night and by the fact that he can't get any sleep. This rhetorical device, incidentally and in case you wondered, whereby an adjective is grammatically applied to one noun, but its sense transferred to another noun in the sentence, is called hypallage. |

|

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read,

Self so self-loving were iniquity. |

Then, when I see myself as I truly am in the mirror, I understand my self love in quite a contrary or different, even opposite way, because such a self-love – meaning a person who so obviously is past their prime thinking so highly of themselves – would be essentially immoral or sinful in the extreme.

|

|

Tis thee, my self, that for myself I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days. |

It is in fact you, my other self, whom I am praising rather than me, and I am painting or decorating or beautifying my age with the beauty of your youth.

The idea that the young lover is Shakespeare's other self, or as we today might put it, other half, that 'we two are one', has come up repeatedly and is also a poetic trope, of course. Shakespeare with this remarkable sonnet effectively recognises that what makes him love himself is his love for his young lover. |

With his most unsparing sonnet so far, Sonnet 62, William Shakespeare finds yet another register and a new level of depth to both his insight into self and the honesty with which he is prepared to sonneteer his young lover. That his lover is young and he by his own perception and standards old could scarcely be more drastically emphasised than in this depiction of himself as misguidedly narcissistic. The greater therefore the redeeming twist that comes in the concluding couplet which once more emphasises not just the close connection Shakespeare feels to his young lover but reiterates, as other sonnets have done before, that he and the young man are, as far as William Shakespeare is concerned, one.

Sonnet 62 is perhaps the most mature and also possibly the most self-effacing of all the sonnets we have encountered so far. And although it is not the first time that Shakespeare highlights the age difference between himself and his young lover – Sonnet 22 was the first one to do so directly and Sonnets 32 and 37 suggested as much – this sonnet here paints a portrait of the poet that is nothing short of starling in its forthrightness:

But when my glass shows me my self indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,

And it won't be long before he follows this up with an even more profound assessment of himself as past his prime with Sonnet 73. So Shakespeare is acutely aware of his age compared to the young man's, which brings back to the foreground of our examination of these sonnets the question we have asked ourselves before: how much older is Shakespeare really than his lover when he writes this? As ever, we can't be sure. But what we know or think we can know with some degree of certainty is this:

Most people date the composition of the majority of The Sonnets in the original collection to sometime between around 1592 when Shakespeare surfaces in London after having been effectively off our radar for seven years, since leaving Stratford-upon-Avon in 1585, and approximately 1598, when they are first mentioned by Francis Meres. As we heard strongly emphasised by Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells, this does not mean that by necessity all these sonnets were written in that six-year window, but all the sonnets we are discussing in this podcast must have been written by 1609 at the extreme latest because that's when they were first published by Thomas Thorpe.

What we know with absolute certainty is that William Shakespeare was born in 1564, and so in 1592 he was 28, by 1609 he was 45. The putative chronological order into which Edmondson and Wells put their edition following the stylometric dating by Macdonald P Jackson has Sonnet 62 some time between 1592 and 1594, which is entirely plausible but it remarkably would have Shakespeare describe himself as "beated and chopped with tanned antiquity" at the age of around 28 to 30. This too, is entirely possible, as we have seen and discussed at some length on previous occasions when we looked at the average life expectancy in Elizabethan England and Shakespeare's perception of age. Without wishing to cover this ground here all over again – you will find more on this in the episodes that concern Sonnets 2 and 37, for example – thirty in Shakespeare's day is advanced in years. And as we saw, for a poet to reach this age without really having had a proper breakthrough would be troubling.

The poem might in theory have been written more than ten years later, when Shakespeare is in his late thirties or early forties, but that would propel it right outside any of the neighbouring sonnets and would presuppose that Shakespeare's principal relationship with a young man started long after he arrived in London. This too is possible but there is no evidence of that as far as we can tell, and it is therefore considerably more likely that Sonnet 62 was written at a time that is congruent with the other sonnets that belong to broadly this group, which would be either in the early or mid-1590s.

In any case, for the young man whom we have been getting to know through these sonnets so far to have any of the qualities clearly ascribed to him, he has to have a degree of agency and independence and that puts him at around 18 or 19 at the very least. The age gap between Shakespeare and him therefore can be at most 17 years, but is far more likely to be in the region of ten or eleven years. This just as a reminder of what kind of time scales we are looking at. We will want to bear this in mind when we come to revisit and look in much more detail at candidates for the young man.

Sonnet 62 is one of the sonnets that appear not to specifically tell us whether it is addressed to a man or a woman, and some people – including Edmondson Wells – therefore count this among the 'open sonnets' that might in theory be addressed to 'anyone'. But a poet 'painting' his age with the beauty of a younger woman connotes really totally differently to him doing so with the beauty of a younger man; and again we can advance as one of the principal additional arguments against imagining a new beautiful character here that there simply is no reasonably strong indication for that being the case. The sonnet makes perfect sense if it is addressed to the same young man as all the others so far, and nothing in it suggests that it is referring itself to someone else.

But beyond that, if we pursue the question whom this particular sonnet is addressed to, then what the sonnet itself tells us is that it is someone of whom Shakespeare thinks as 'my self': my other half. Could this be some random person of any gender? In theory it could. Is that likely? Not very. If I am in love with someone whom I describe as a part of me, it is extremely likely to be the same person whom elsewhere I have told is the better part of me, of whom elsewhere I have said that we two are one. It would be very strange behaviour indeed – not impossible, granted, but almost unthinkable – that Shakespeare, who after all is a working actor and playwright, who has to earn a living and send money to his family in Stratford, who finds himself touring on occasion whilst running a theatre company, has time, brain space, and the capacity of heart to involve in his life a whole raft of people to whom he writes intense poetry. One simply makes more sense; granted perhaps not one over the entire period that he is in London, but we will learn more about this likely addressee, and we will learn specifically about the duration of this relationship, and so in the absence of any other evidence that strongly points to a different person, we are absolutely entitled to think of this as – so far, at the very least – one young man.

Here is therefore not a bad place to reiterate: in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. We cannot know anything for certain, everybody admits as much, but we can talk about greater and lesser degrees of likelihood, and here my understanding very strongly is that the likelihood is not that the likelihood is not that we are here now talking about somebody else, somebody new, or somebody random, but about somebody with whom Shakespeare is strongly connected enough to tell him that 'you are me, we two are one', just as he did in Sonnet 22. Can we rule out that he says the same thing essentially to two entirely different people? Of course we can't. Do we need to consider it likely? I believe not so, but you will be able to make up your own minds, I hope, by and by.

What makes Sonnet 62 stand out above all though is its postulate of a sinful self-love in Shakespeare. It is, as we noted, new, and therefore invites the question, as a new tone or element naturally does: what brings this on? What prompts this? Any answer we may attempt to this has to be pure speculation. The words themselves do not provide one. And so if we continue to simply listen to the words and what they tell us, we have to once more, as so very often during our journey of discovery, shrug our shoulders and say: we don't know. It has been suggested that the sonnet may be a response to criticism Shakespeare might have received from the young man following a few fairly self-indulgent sonnets, namely Sonnets 57 & 58, and the one just preceding this, Sonnet 61. This is not to be ruled out. We do not know whether the sequence of composition breaks after 60 with any more certainty than we can know what, if any, reaction any of these sonnets elicit from their recipient, and we don't even know, as we keep reminding ourselves, with any certainty who this recipient is, or whether he, or they, ever receive and read or hear these sonnets, even though we know with some certainty that by 1598 at least some of these sonnets circulate among Shakespeare's "private friends."

But as plausible explanations go, this is certainly one: say you are in a complex, somewhat asymmetric relationship – and of this we can be pretty certain, or, perhaps to be more precise, this is certainly the impression we get from the words of these sonnets alone – and you have just fired off a salvo of sonnets to your young, very independent-minded, exceptionally beautiful but also fickle and unfaithful lover whom you may or may not be in a financially involved constellation with, first sarcastically and, as we in contemporary terms labelled it, somewhat passive-aggressively, telling him, look I am your slave, you can do whatever you want with whomever you choose, I'll just wait here and count those lucky who are receiving the benefit of your fabulous company and far be it from me to even guess what you're up to, as it is clearly none of my business, followed, possibly after a short gap, though who knows whether Sonnets 59 and 60 are exactly in the right place either, by a poem asking, again in a semi-ironic tone, some rhetorical questions about the lover's interest in what I am up to only to then conclude, ah no, your love does not reach that far, it is my love for you which keeps me awake while you are away somewhere with other people way too near for mere comfort; say you have just done that, then it is absolutely not beyond the realms of the imagination that this young man, of whom we know that he doesn't like being told what to do, at one point turns around and says, Will. Pull yourself together. It's not all about you, you know. And to this, a response saying: it is true, I am being self-indulgent here, but actually, if it comes across as if I love myself and put myself above everyone else, then this is only because I love you, does make some sense.

But we need to treat this sort of deduction with extreme caution. Firstly because it comes close to being contorted, and secondly because we may simply want to read it this way, because it fits our narrative and that, though attractive, may yet be fiction. What we can take from Sonnet 62 is a disturbance, and an imbalance, and a self-reflection that takes on a physical dimension and contrasts the lover's youth and beauty with Shakespeare's age and, as he is about to describe it a sense of self that is, "with time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn." And this theme continues, reinforced, and is explored to increasingly striking effect, twice interspersed with reiterations of Shakespeare's faith in his own writing, in Sonnet 63 as a fairly confident prediction, in Sonnet 65 expressed more as a tentative hope, before with Sonnet 66, a poetic bombshell explodes which shows us a Shakespeare we have not seen before.

Sonnet 62 is perhaps the most mature and also possibly the most self-effacing of all the sonnets we have encountered so far. And although it is not the first time that Shakespeare highlights the age difference between himself and his young lover – Sonnet 22 was the first one to do so directly and Sonnets 32 and 37 suggested as much – this sonnet here paints a portrait of the poet that is nothing short of starling in its forthrightness:

But when my glass shows me my self indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,

And it won't be long before he follows this up with an even more profound assessment of himself as past his prime with Sonnet 73. So Shakespeare is acutely aware of his age compared to the young man's, which brings back to the foreground of our examination of these sonnets the question we have asked ourselves before: how much older is Shakespeare really than his lover when he writes this? As ever, we can't be sure. But what we know or think we can know with some degree of certainty is this:

Most people date the composition of the majority of The Sonnets in the original collection to sometime between around 1592 when Shakespeare surfaces in London after having been effectively off our radar for seven years, since leaving Stratford-upon-Avon in 1585, and approximately 1598, when they are first mentioned by Francis Meres. As we heard strongly emphasised by Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells, this does not mean that by necessity all these sonnets were written in that six-year window, but all the sonnets we are discussing in this podcast must have been written by 1609 at the extreme latest because that's when they were first published by Thomas Thorpe.

What we know with absolute certainty is that William Shakespeare was born in 1564, and so in 1592 he was 28, by 1609 he was 45. The putative chronological order into which Edmondson and Wells put their edition following the stylometric dating by Macdonald P Jackson has Sonnet 62 some time between 1592 and 1594, which is entirely plausible but it remarkably would have Shakespeare describe himself as "beated and chopped with tanned antiquity" at the age of around 28 to 30. This too, is entirely possible, as we have seen and discussed at some length on previous occasions when we looked at the average life expectancy in Elizabethan England and Shakespeare's perception of age. Without wishing to cover this ground here all over again – you will find more on this in the episodes that concern Sonnets 2 and 37, for example – thirty in Shakespeare's day is advanced in years. And as we saw, for a poet to reach this age without really having had a proper breakthrough would be troubling.

The poem might in theory have been written more than ten years later, when Shakespeare is in his late thirties or early forties, but that would propel it right outside any of the neighbouring sonnets and would presuppose that Shakespeare's principal relationship with a young man started long after he arrived in London. This too is possible but there is no evidence of that as far as we can tell, and it is therefore considerably more likely that Sonnet 62 was written at a time that is congruent with the other sonnets that belong to broadly this group, which would be either in the early or mid-1590s.

In any case, for the young man whom we have been getting to know through these sonnets so far to have any of the qualities clearly ascribed to him, he has to have a degree of agency and independence and that puts him at around 18 or 19 at the very least. The age gap between Shakespeare and him therefore can be at most 17 years, but is far more likely to be in the region of ten or eleven years. This just as a reminder of what kind of time scales we are looking at. We will want to bear this in mind when we come to revisit and look in much more detail at candidates for the young man.

Sonnet 62 is one of the sonnets that appear not to specifically tell us whether it is addressed to a man or a woman, and some people – including Edmondson Wells – therefore count this among the 'open sonnets' that might in theory be addressed to 'anyone'. But a poet 'painting' his age with the beauty of a younger woman connotes really totally differently to him doing so with the beauty of a younger man; and again we can advance as one of the principal additional arguments against imagining a new beautiful character here that there simply is no reasonably strong indication for that being the case. The sonnet makes perfect sense if it is addressed to the same young man as all the others so far, and nothing in it suggests that it is referring itself to someone else.

But beyond that, if we pursue the question whom this particular sonnet is addressed to, then what the sonnet itself tells us is that it is someone of whom Shakespeare thinks as 'my self': my other half. Could this be some random person of any gender? In theory it could. Is that likely? Not very. If I am in love with someone whom I describe as a part of me, it is extremely likely to be the same person whom elsewhere I have told is the better part of me, of whom elsewhere I have said that we two are one. It would be very strange behaviour indeed – not impossible, granted, but almost unthinkable – that Shakespeare, who after all is a working actor and playwright, who has to earn a living and send money to his family in Stratford, who finds himself touring on occasion whilst running a theatre company, has time, brain space, and the capacity of heart to involve in his life a whole raft of people to whom he writes intense poetry. One simply makes more sense; granted perhaps not one over the entire period that he is in London, but we will learn more about this likely addressee, and we will learn specifically about the duration of this relationship, and so in the absence of any other evidence that strongly points to a different person, we are absolutely entitled to think of this as – so far, at the very least – one young man.

Here is therefore not a bad place to reiterate: in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. We cannot know anything for certain, everybody admits as much, but we can talk about greater and lesser degrees of likelihood, and here my understanding very strongly is that the likelihood is not that the likelihood is not that we are here now talking about somebody else, somebody new, or somebody random, but about somebody with whom Shakespeare is strongly connected enough to tell him that 'you are me, we two are one', just as he did in Sonnet 22. Can we rule out that he says the same thing essentially to two entirely different people? Of course we can't. Do we need to consider it likely? I believe not so, but you will be able to make up your own minds, I hope, by and by.

What makes Sonnet 62 stand out above all though is its postulate of a sinful self-love in Shakespeare. It is, as we noted, new, and therefore invites the question, as a new tone or element naturally does: what brings this on? What prompts this? Any answer we may attempt to this has to be pure speculation. The words themselves do not provide one. And so if we continue to simply listen to the words and what they tell us, we have to once more, as so very often during our journey of discovery, shrug our shoulders and say: we don't know. It has been suggested that the sonnet may be a response to criticism Shakespeare might have received from the young man following a few fairly self-indulgent sonnets, namely Sonnets 57 & 58, and the one just preceding this, Sonnet 61. This is not to be ruled out. We do not know whether the sequence of composition breaks after 60 with any more certainty than we can know what, if any, reaction any of these sonnets elicit from their recipient, and we don't even know, as we keep reminding ourselves, with any certainty who this recipient is, or whether he, or they, ever receive and read or hear these sonnets, even though we know with some certainty that by 1598 at least some of these sonnets circulate among Shakespeare's "private friends."

But as plausible explanations go, this is certainly one: say you are in a complex, somewhat asymmetric relationship – and of this we can be pretty certain, or, perhaps to be more precise, this is certainly the impression we get from the words of these sonnets alone – and you have just fired off a salvo of sonnets to your young, very independent-minded, exceptionally beautiful but also fickle and unfaithful lover whom you may or may not be in a financially involved constellation with, first sarcastically and, as we in contemporary terms labelled it, somewhat passive-aggressively, telling him, look I am your slave, you can do whatever you want with whomever you choose, I'll just wait here and count those lucky who are receiving the benefit of your fabulous company and far be it from me to even guess what you're up to, as it is clearly none of my business, followed, possibly after a short gap, though who knows whether Sonnets 59 and 60 are exactly in the right place either, by a poem asking, again in a semi-ironic tone, some rhetorical questions about the lover's interest in what I am up to only to then conclude, ah no, your love does not reach that far, it is my love for you which keeps me awake while you are away somewhere with other people way too near for mere comfort; say you have just done that, then it is absolutely not beyond the realms of the imagination that this young man, of whom we know that he doesn't like being told what to do, at one point turns around and says, Will. Pull yourself together. It's not all about you, you know. And to this, a response saying: it is true, I am being self-indulgent here, but actually, if it comes across as if I love myself and put myself above everyone else, then this is only because I love you, does make some sense.

But we need to treat this sort of deduction with extreme caution. Firstly because it comes close to being contorted, and secondly because we may simply want to read it this way, because it fits our narrative and that, though attractive, may yet be fiction. What we can take from Sonnet 62 is a disturbance, and an imbalance, and a self-reflection that takes on a physical dimension and contrasts the lover's youth and beauty with Shakespeare's age and, as he is about to describe it a sense of self that is, "with time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn." And this theme continues, reinforced, and is explored to increasingly striking effect, twice interspersed with reiterations of Shakespeare's faith in his own writing, in Sonnet 63 as a fairly confident prediction, in Sonnet 65 expressed more as a tentative hope, before with Sonnet 66, a poetic bombshell explodes which shows us a Shakespeare we have not seen before.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!