Sonnet 43: When Most I Wink, Then Do Mine Eyes Best See

|

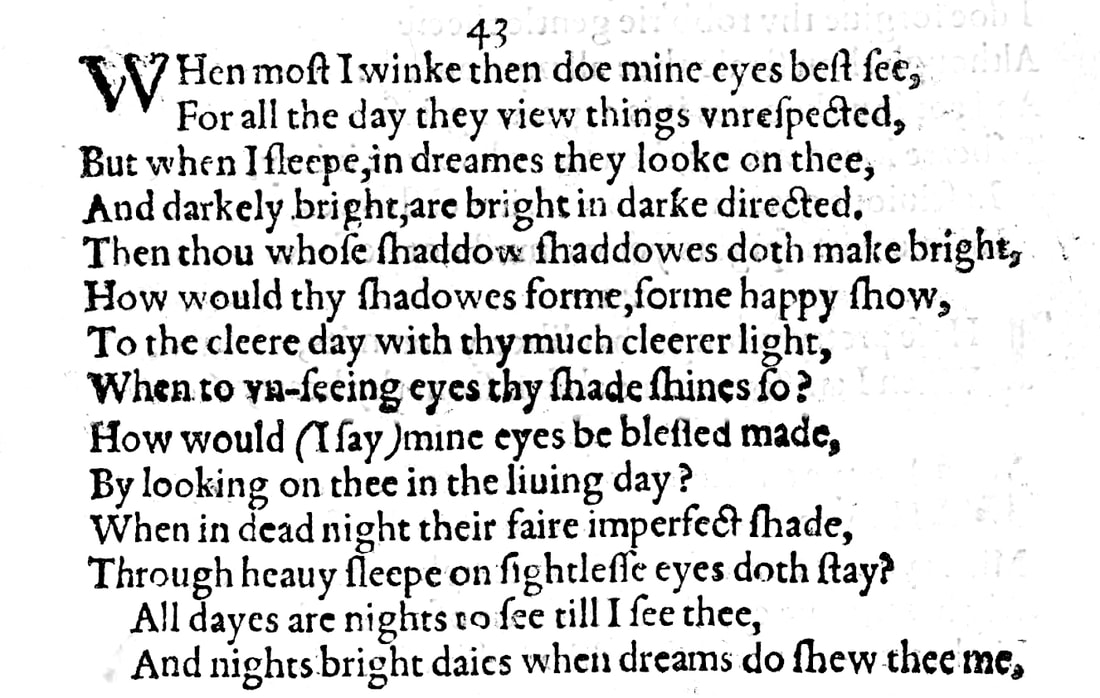

When most I wink, then do mine eyes best see,

For all the day they view things unrespected; But when I sleep, in dreams they look on thee, And darkly bright are bright in dark directed. Then thou, whose shadow shadows doth make bright, How would thy shadow's form form happy show To the clear day with thy much clearer light, When to unseeing eyes thy shade shines so? How would, I say, mine eyes be blessed made By looking on thee in the living day, When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay? All days are nights to see till I see thee, And nights bright days when dreams do show thee me. |

|

When most I wink, then do mine eyes best see,

|

When I am most soundly asleep, then are my eyes best able to see...

On the surface 'to wink' here simply means to sleep, much as the quaint expression 'to take forty winks' means to take a nap, and so the time when I most wink is the time when I am most soundly asleep. It has been suggested though that in light of the young man's recent infidelity, 'wink' here may also have a secondary meaning of 'to turn a blind eye'. This is entirely possible, but not altogether convincing, since nothing else in this sonnet, or the two pairs that follow, appears to reference those events, and so I am inclined to read this line without any pun intended. |

|

For all the day they view things unrespected;

|

...because all through the day they – my eyes – look at things that are unimportant to me and which I therefore don't greatly honour with my respect.

The implied reason why everything that I, the poet, look at during the day is unimportant to me is that I am away from you and therefore everything that I look at is not you, as will become explicitly clear in just a moment: |

|

But when I sleep, in dreams they look on thee

|

But when I am asleep, then in my dreams my eyes look at you...

|

|

And darkly bright are bright in dark directed.

|

And although my eyes are closed and therefore dark, they are seeing as if they were awake and are therefore bright – they are "darkly bright" – and they are guided to you by your bright beauty that appears in the dark night: they are "bright in dark directed."

Shakespeare's understanding of light would have been informed by the pre-Newtonian science of his day, which assumed that the rays of vision emanate from the eye to the object which the eye is looking at. And so for him and his contemporaries, the human eye is not merely a recipient of light rays, but also a source and emitter of light. |

|

Then thou, whose shadow shadows doth make bright,

|

That being the case: you being such a bright presence that even a mere vision of you appearing to me in a dream is capable of brightening the dark shadows of the night...

We have encountered 'shadow' as a vision before, in Sonnet 27, which this sonnet appears to relate to thematically, and we have also previously noted just how dark a moonless night in the English countryside could be in those days. |

|

How would thy shadow's form form happy show

To the clear day with thy much clearer light |

...how would the form that lies behind this 'shadow', this vision I have of you in my dream, namely you yourself in your physical presence, be able to form a pleasing or delightful spectacle – a happy show or a show that makes me happy – in the clear light of day with your light that is much brighter still than the day itself...

|

|

When to unseeing eyes thy shade shines so.

|

...when even your 'shadow' – again my vision of you – shines so brightly to my eyes, which are closed because I am asleep and which therefore can't actually really see anything.

|

|

How would, I say, mine eyes be blessed made

By looking on thee in the living day, |

How, in other words, would my eyes be blessed by being able to look at you in the living daylight....

|

|

When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade

Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay? |

...when in fact in the dead of night your beautiful and bright 'shadow', for which still and always here read vision or apparition, rests with my closed and therefore sightless eyes through my deep sleep.

'Fair' here receives a pointed double meaning of both 'beautiful' as we have encountered often, and also 'light' or even 'bright'. The culture of the day strongly associates light with beauty and goodness, and darkness with danger, menace, and ugliness. The rhetorical question posed by these two highly complex quatrains in simple terms is: given how beautiful and clear and bright you appear to me in my dreams at night, what additional benefit or pleasure would I gain from being able to look upon you in real life during the daytime? As has been the case once or twice before, the logic isn't quite right, but the closing couplet sums up the argument neatly: |

|

All days are nights to see till I see thee,

And nights bright days when dreams do show thee me. |

Because all days are dark as night to me until I can see you again, and in turn all nights are as bright as daylight to me, when my dreams show you to me.

Ordinarily we would expect the final part of the last sentence to read: '...when dreams do show me thee'. The inversion to "when dreams do show thee me" is likely prompted purely by the need for a real rhyme and rhyming 'thee' with 'thee' would not suffice since a word can't really rhyme with itself. But it has the added and delicately pleasing effect that the line thus can also be understood as: until dreams show me to you, which, as John Kerrigan points out, evokes the notion of two people looking at each other in their respective dreams. In view of what has just happened and the anxieties that agitate Shakespeare in sonnets to come, this may, it has to be said, be rather wishful thinking, either on our part or, if it is intended, on Shakespeare's part. |

Sonnet 43 leaves behind, for the time-being, the upheaval and upset caused by the young man's betrayal of Shakespeare with his own mistress and picks up the theme – and to a lesser extent mood – of Sonnets 27 & 28 when Shakespeare – away from his young lover and tired with travel – is kept awake by the beautiful young man's vision appearing to him in his dreams.

That said, it does not, as some sonnets do, create a direct link that would tie it to these earlier sonnets, and so there is no obvious reason why we should assume that 43 belongs there rather than here, though that is certainly a possibility. In fact, there are several sonnets coming up now that meditate on the pain of separation, interspersed with ones that open up a vast spectrum of emotions, ranging from the dejected to the exalted and so, perhaps to somewhat cheekily invoke Bette Davis, we probably had better fasten our safety belts, because these next eighteen poems are going to make for a bumpy but exciting ride, notwithstanding the fact that it starts quite abstract...

Sonnet 43 may be one of the most semantically difficult sonnets to decipher, even though its argument is reassuringly simple: your beauty and your brilliance is such that with your appearance in my dreams you turn my darkest nights into daylight, and your absence plunges even the brightest day into a dark and lonely night.

The way the sonnet is written though is anything but simple and that, if nothing else, begs the question: why? Why is William Shakespeare, who we know can express himself with compelling power poetically but directly, constructing such a complicated cascade of thoughts? And this not, it has to be said, in the most convincing manner. Because much as on two or three previous occasions, the logic doesn't actually stack up: Will is saying to his young lover that on the one hand he doesn't need to look at him in broad daylight because his eyes could not be "more blessed made," meaning happier, more fortunate, more pleased, by doing so, since what they see when they are shut and he is dreaming is in itself so satisfying. Yet in the next breath he then effectively contradicts this by saying that daytime is turned into night when he can't see his lover. On those previous occasions we noted that logic is not perhaps Shakespeare's strongest suit and this skilful but curiously dry poem would seem to support that impression we have been getting.

We don't know, of course, what specifically and precisely prompts Shakespeare to write this sonnet, other than that it appears evident he is either still or again separated from his young lover, and there are two elements that may offer themselves as possible contributing factors to a person's poetry going slightly disjointed, as arguably this and the ensuing two couples of sonnets, 44 & 45 and 46 & 47 might be considered to be, since they all engage in fairly elaborate verbal acrobatics to make some not particularly pertinent points. And these two factors are: boredom and limbo.

This, it has to be emphasised strongly, is pure speculation: we simply remain in the dark as to what exactly is going on with our poet, but holding on to our principal premise that we have the words, and the words are a direct expression, or at the very least an indirect reflection, of Shakespeare's state of mind and heart at the time of writing, then viewing this and the next two times two sonnets through this lens would make some sense.

If William Shakespeare had recently returned to London after being away from his young lover, only to be confronted with the news that during his absence the young man had embarked on an encounter or a fling or some sort of sexual experience with a woman Shakespeare himself considers his mistress, and now – after maybe not all that much time has passed – he finds himself newly on the road, then keeping himself busy with emotionally undercharged but 'intellectually' or at any rate verbally fairly sophisticated exercises would be an obvious and acceptable way of passing the long hours of absence. And it is perhaps no coincidence that at this particular juncture 'sophisticated' may be sliding somewhat closer to 'sophistic'. Because the argument here being made, as indeed the ones in the two following pairs, are well constructed, but they are also devoid of passion or urgency. It isn't really until Sonnet 48 that a sense of direct, personal involvement truly returns. Which is not to say that these five sonnets are therefore pointless or irrelevant. But they do convey a level of detachment and they come across as writing that is being done much more for writing's sake than anything else.

And so these two elements bear giving thought to just for one moment longer: boredom and limbo. Many of the sonnets we have heard and seen so far feel so contemporary and so relatable that we may forget how, while in certain and profoundly human respects Shakespeare and his loves were just like us, in many practical terms their lives were really quite categorically different from ours. In an age before electricity, telecommunication, and computing, a message from your lover can take days to arrive. If they don't have the time or brain space – or the inclination – to write, you may hear nothing from them at all for weeks. There are few forms of entertainment and stimulation in the cities, and almost none in the country. Travel, as we have seen and heard from Shakespeare himself, is arduous and tiring. The nights, for much of the year, are long and dark. If you are a writer – say a poet or a playwright, like William Shakespeare, and you are away from London and your lover, and you have no commission to write a play, because the theatres are closed for the plague, but you're earning your living as a touring actor, for example, or maybe as a teacher or instructor, you may have restricted means, but a fair amount of time on your hand, and a deep sense of uncertainty about what is going on back home; home here meaning London and your young lover, because we don't get any sense that Shakespeare ever needs to worry a great deal about what is going on at his family home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Boredom and limbo. And perhaps a degree of self-sufficiency inside your head: the lover you are thinking of, dreaming of, of whom you wish you could be with him: you can keep him present in your thoughts, your heart, your being, by writing to and for and about him. You can alleviate both boredom and limbo, by composing poetry.

And let us not forget: we have no idea what, if anything, anybody around Shakespeare knows of this relationship. Can he talk to his actor colleagues and friends about his lover when he's away from home? We genuinely don't know: quite possibly he can. We should not assume that just because we've since been through periods of abject puritanism and appear to be heading straight for another, the men and boys who make up the Lord Chamberlain's Men and later the King's Men might not be quite worldly and fairly clued up about all kinds of connections, including their good Will's love life. But we also know that scandal can be existentially dangerous, and status and reputation may be matters of life and death. So it may well be the case that for Shakespeare, while he is away from his lover, the pen and the poem are really what keep him going and sane.

There is, with Sonnet 43, and through 44 & 45 and Sonnets 46 & 47, something of a hiatus in the turbulence of Shakespeare's existence, but what these poems possibly lack in drama, they most certainly make up for in writerly dexterity and poetic playfulness.

That said, it does not, as some sonnets do, create a direct link that would tie it to these earlier sonnets, and so there is no obvious reason why we should assume that 43 belongs there rather than here, though that is certainly a possibility. In fact, there are several sonnets coming up now that meditate on the pain of separation, interspersed with ones that open up a vast spectrum of emotions, ranging from the dejected to the exalted and so, perhaps to somewhat cheekily invoke Bette Davis, we probably had better fasten our safety belts, because these next eighteen poems are going to make for a bumpy but exciting ride, notwithstanding the fact that it starts quite abstract...

Sonnet 43 may be one of the most semantically difficult sonnets to decipher, even though its argument is reassuringly simple: your beauty and your brilliance is such that with your appearance in my dreams you turn my darkest nights into daylight, and your absence plunges even the brightest day into a dark and lonely night.

The way the sonnet is written though is anything but simple and that, if nothing else, begs the question: why? Why is William Shakespeare, who we know can express himself with compelling power poetically but directly, constructing such a complicated cascade of thoughts? And this not, it has to be said, in the most convincing manner. Because much as on two or three previous occasions, the logic doesn't actually stack up: Will is saying to his young lover that on the one hand he doesn't need to look at him in broad daylight because his eyes could not be "more blessed made," meaning happier, more fortunate, more pleased, by doing so, since what they see when they are shut and he is dreaming is in itself so satisfying. Yet in the next breath he then effectively contradicts this by saying that daytime is turned into night when he can't see his lover. On those previous occasions we noted that logic is not perhaps Shakespeare's strongest suit and this skilful but curiously dry poem would seem to support that impression we have been getting.

We don't know, of course, what specifically and precisely prompts Shakespeare to write this sonnet, other than that it appears evident he is either still or again separated from his young lover, and there are two elements that may offer themselves as possible contributing factors to a person's poetry going slightly disjointed, as arguably this and the ensuing two couples of sonnets, 44 & 45 and 46 & 47 might be considered to be, since they all engage in fairly elaborate verbal acrobatics to make some not particularly pertinent points. And these two factors are: boredom and limbo.

This, it has to be emphasised strongly, is pure speculation: we simply remain in the dark as to what exactly is going on with our poet, but holding on to our principal premise that we have the words, and the words are a direct expression, or at the very least an indirect reflection, of Shakespeare's state of mind and heart at the time of writing, then viewing this and the next two times two sonnets through this lens would make some sense.

If William Shakespeare had recently returned to London after being away from his young lover, only to be confronted with the news that during his absence the young man had embarked on an encounter or a fling or some sort of sexual experience with a woman Shakespeare himself considers his mistress, and now – after maybe not all that much time has passed – he finds himself newly on the road, then keeping himself busy with emotionally undercharged but 'intellectually' or at any rate verbally fairly sophisticated exercises would be an obvious and acceptable way of passing the long hours of absence. And it is perhaps no coincidence that at this particular juncture 'sophisticated' may be sliding somewhat closer to 'sophistic'. Because the argument here being made, as indeed the ones in the two following pairs, are well constructed, but they are also devoid of passion or urgency. It isn't really until Sonnet 48 that a sense of direct, personal involvement truly returns. Which is not to say that these five sonnets are therefore pointless or irrelevant. But they do convey a level of detachment and they come across as writing that is being done much more for writing's sake than anything else.

And so these two elements bear giving thought to just for one moment longer: boredom and limbo. Many of the sonnets we have heard and seen so far feel so contemporary and so relatable that we may forget how, while in certain and profoundly human respects Shakespeare and his loves were just like us, in many practical terms their lives were really quite categorically different from ours. In an age before electricity, telecommunication, and computing, a message from your lover can take days to arrive. If they don't have the time or brain space – or the inclination – to write, you may hear nothing from them at all for weeks. There are few forms of entertainment and stimulation in the cities, and almost none in the country. Travel, as we have seen and heard from Shakespeare himself, is arduous and tiring. The nights, for much of the year, are long and dark. If you are a writer – say a poet or a playwright, like William Shakespeare, and you are away from London and your lover, and you have no commission to write a play, because the theatres are closed for the plague, but you're earning your living as a touring actor, for example, or maybe as a teacher or instructor, you may have restricted means, but a fair amount of time on your hand, and a deep sense of uncertainty about what is going on back home; home here meaning London and your young lover, because we don't get any sense that Shakespeare ever needs to worry a great deal about what is going on at his family home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Boredom and limbo. And perhaps a degree of self-sufficiency inside your head: the lover you are thinking of, dreaming of, of whom you wish you could be with him: you can keep him present in your thoughts, your heart, your being, by writing to and for and about him. You can alleviate both boredom and limbo, by composing poetry.

And let us not forget: we have no idea what, if anything, anybody around Shakespeare knows of this relationship. Can he talk to his actor colleagues and friends about his lover when he's away from home? We genuinely don't know: quite possibly he can. We should not assume that just because we've since been through periods of abject puritanism and appear to be heading straight for another, the men and boys who make up the Lord Chamberlain's Men and later the King's Men might not be quite worldly and fairly clued up about all kinds of connections, including their good Will's love life. But we also know that scandal can be existentially dangerous, and status and reputation may be matters of life and death. So it may well be the case that for Shakespeare, while he is away from his lover, the pen and the poem are really what keep him going and sane.

There is, with Sonnet 43, and through 44 & 45 and Sonnets 46 & 47, something of a hiatus in the turbulence of Shakespeare's existence, but what these poems possibly lack in drama, they most certainly make up for in writerly dexterity and poetic playfulness.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!