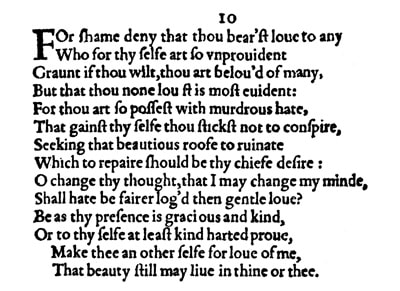

Sonnet 10: For Shame Deny That Thou Bearst Love to Any

|

For shame deny that thou bearst love to any,

Who for thyself art so unprovident. Grant if thou wilt, thou art beloved of many, But that thou none lovest is most evident, For thou art so possessed with murderous hate That gainst thyself thou stickst not to conspire, Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate Which to repair should be thy chief desire. O change thy thought that I may change my mind; Shall hate be fairer lodged than gentle love? Be as thy presence is: gracious and kind; Or to thyself at least kindhearted prove: Make thee another self for love of me, That beauty still may live in thine or thee. |

|

For shame deny that thou bearst love to any

Who for thyself art so unprovident. |

Shame on you if you claim that you bear love to anybody, when you yourself are so improvident on your own behalf.

Although "for shame" is a standard exclamation, the word 'shame' here also directly links this sonnet to the last line of the previous sonnet, and while the connection between the two sonnets otherwise isn't quite strong enough to make them appear as a couple, it is nevertheless telling that Shakespeare picks up on the "murderous shame" he somewhat ambiguously accused the young man of in Sonnet 9. 'Deny', meanwhile, has almost the opposite meaning of what we would today use the word for, as it conveys more a sense of 'protest' or 'claim', as in: For shame, protest that you actually love anyone. Unless we read "any" as 'nobody', so the line means: For shame deny the accusation that you don't bear love to anybody. Which is of course set up in the previous sonnet too: "No love toward others in that bosom sits That on himself such murderous shame commits." Either way, the poet ups the stakes again by holding on to the idea of love introduced only in the last sonnet, and telling the young man that he clearly doesn't love anybody, much as suggested just then. |

|

Grant if thou wilt, thou art beloved of many,

But that thou none lovest is most evident, |

And here he spells it out: granted, you are loved by many, but it is totally obvious that you love no-one...

PRONUNCIATION: Note that lovest is pronounced as one syllable: lov'st. |

|

For thou art so possessed with murderous hate

|

...because you are so possessed with murderous hate...

The "murderous" obviously now also echoes the "murderous shame" with which Sonnet 9 closes. PRONUNCIATION: Note that here too murderous is pronounced with two syllables: mur-d'rous. |

|

That gainst thyself thou stickst not to conspire

|

...that you don't stop at conspiring against yourself...

|

|

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire. |

...but you go beyond damaging yourself and actively seek to ruin that beautiful house which to keep up should be your greatest concern.

The "roof" here stands for 'house' in the sense of a family name and estate, as in the House of Windsor, or the House of Usher. The young man, upon whose shoulders the responsibility rests to maintain his lineage, should make keeping this metaphorical house 'in good repair' – meaning alive and well – his greatest ambition and wish, and as we have seen and understood throughout this early part of the sequence, that entails producing an heir who can continue the line. |

|

O change thy thought that I may change my mind;

|

Oh change your way of thinking – about marriage, having children, your responsibility – so that I may change my mind about you, specifically with regard to whether you love anyone or not.

This is the first time we hear the poet refer to himself, and that, as we shall see, and for whatever reason this happens, changes the whole dynamic dramatically. |

|

Shall hate be fairer lodged than gentle love?

|

Shall hate – which I believe to detect in your attitude and actions – be at home in a more beautiful person than gentle love?

The fact that the Fair Youth is beautiful is well established by now, and the rhetorical question is asking him whether he can really allow for hate to live in such a beautiful person as he is, which by necessity means that hate is then more beautifully housed than love, since wherever love lives, its dwelling – that person – cannot be more beautiful than the young man, as he is clearly the most beautiful of them all. |

|

Be as thy presence is: gracious and kind;

|

Be – in your actions, thoughts, demeanour – just as you look and come across face-to-face, namely gracious and kind...

|

|

Or to thyself at least kindhearted prove:

|

Or if you can't find it in yourself to be kind and gracious to others or to someone else, then at least prove kind to yourself:

|

|

Make thee another self for love of me

That beauty still may live in thine or thee. |

And a direct contraction paired with a bold request: make a child for the love of me, so that your beauty may continue to live both in your child – thine – and in yourself.

|

The spectacular Sonnet 10 boldly goes where no sonnet in the series so far has gone before and radically changes the tone and the dynamic between the poet and the young man.

Striking about this sonnet at first glance are three things:

1 - William Shakespeare directly references the previous Sonnet 9, by picking up on the "murderous shame" of which he accuses, or for which at any rate he admonishes, the young man there on the one hand, and by continuing his elaboration on the there newly introduced theme of 'love', on the other. And so although Sonnets 9 and 10 can't strictly be viewed as a pair or a unit, they do very clearly follow on from each other and Shakespeare seems to rather be upping the ante here by then piling on strong, so as not to say hyperbolic language: "that thou none lovest is most evident" is surely something of an exaggeration, as is "possessed with murderous hate," and even "ruinate" sounds just a tad over the top.

2 – William Shakespeare enters the frame. We wondered – somewhat adventurously, one might argue – in Sonnet 6 whether "self-willed" might be a pun on Will's name, but there really is no compelling or conclusive evidence of that there. Here though we can be in no doubt that the poet is introducing the first person singular, which means he is either referring directly to himself as the composer of this poem, or he assumes the mantle of the person on whose behalf he is writing. This latter is a possibility, but it doesn't seem particularly strong: surely, if the poet has been asked to write these poems by somebody else, then one of two things must apply: either the young man is already familiar with this person – his mother, for instance – and has shown little regard for their wishes; or he doesn't know who this person is, in which case the only sensible thing for the poet to do would be to name or at the very least obliquely refer to them, rather than, without explanation, stepping into their position as the speaker, and making everything far more interesting that way.

3 – Most thrillingly though, I the poet, William Shakespeare, here not only put myself in the poem, asking the young man to change his "thought so I may change my mind" about him, but I then go several steps further by suggesting he do so "for love of me."

All these three in combination, but particularly of course the third and last point, make for a radical change in tone. Not long ago we observed that the poet sounded effectively uninvolved; we even, a short while ago, suggested he might possibly be getting a little bored with his task, but here now he really spices things up by putting himself in the mix and doing so in a direct vector towards the young man.

And there is one more potentially telling and therefore tantalising detail: "be as thy presence is, gracious and kind." You may remember we talked before about how some of the things the poet says about the young man sound fairly generic. So much so that one could entirely imagine Shakespeare simply having been told about the young man, and possibly having seen a picture of him or occasionally spotted him, perhaps at the theatre. But here now I, the poet, make a specific claim not just as to how the young man looks but also how he is: gracious and kind. And I relate this to his presence. And in order for me to be able to make such a claim I must have either experienced the young man's presence, or for good enough reason feel as if I had. And on top of that I must have some reason why I believe the young man would do anything "for love of me:" you cannot ask somebody who has no reason at all to care about, or to have any interest in, you to do something for love of you. But here Shakespeare puts it out there on paper, directly in front of the young man: do this for love of me.

And so something has shifted. The tone most certainly has. The language is stronger, directer, bolder, and way more personal than it has been, and we now have a direct connection between the poet and the young man in the words themselves. And this is after all our approach: to listen to the words and find out what they themselves tell us.

And most fortuitously, fairly soon they will tell us a good deal more...

Striking about this sonnet at first glance are three things:

1 - William Shakespeare directly references the previous Sonnet 9, by picking up on the "murderous shame" of which he accuses, or for which at any rate he admonishes, the young man there on the one hand, and by continuing his elaboration on the there newly introduced theme of 'love', on the other. And so although Sonnets 9 and 10 can't strictly be viewed as a pair or a unit, they do very clearly follow on from each other and Shakespeare seems to rather be upping the ante here by then piling on strong, so as not to say hyperbolic language: "that thou none lovest is most evident" is surely something of an exaggeration, as is "possessed with murderous hate," and even "ruinate" sounds just a tad over the top.

2 – William Shakespeare enters the frame. We wondered – somewhat adventurously, one might argue – in Sonnet 6 whether "self-willed" might be a pun on Will's name, but there really is no compelling or conclusive evidence of that there. Here though we can be in no doubt that the poet is introducing the first person singular, which means he is either referring directly to himself as the composer of this poem, or he assumes the mantle of the person on whose behalf he is writing. This latter is a possibility, but it doesn't seem particularly strong: surely, if the poet has been asked to write these poems by somebody else, then one of two things must apply: either the young man is already familiar with this person – his mother, for instance – and has shown little regard for their wishes; or he doesn't know who this person is, in which case the only sensible thing for the poet to do would be to name or at the very least obliquely refer to them, rather than, without explanation, stepping into their position as the speaker, and making everything far more interesting that way.

3 – Most thrillingly though, I the poet, William Shakespeare, here not only put myself in the poem, asking the young man to change his "thought so I may change my mind" about him, but I then go several steps further by suggesting he do so "for love of me."

All these three in combination, but particularly of course the third and last point, make for a radical change in tone. Not long ago we observed that the poet sounded effectively uninvolved; we even, a short while ago, suggested he might possibly be getting a little bored with his task, but here now he really spices things up by putting himself in the mix and doing so in a direct vector towards the young man.

And there is one more potentially telling and therefore tantalising detail: "be as thy presence is, gracious and kind." You may remember we talked before about how some of the things the poet says about the young man sound fairly generic. So much so that one could entirely imagine Shakespeare simply having been told about the young man, and possibly having seen a picture of him or occasionally spotted him, perhaps at the theatre. But here now I, the poet, make a specific claim not just as to how the young man looks but also how he is: gracious and kind. And I relate this to his presence. And in order for me to be able to make such a claim I must have either experienced the young man's presence, or for good enough reason feel as if I had. And on top of that I must have some reason why I believe the young man would do anything "for love of me:" you cannot ask somebody who has no reason at all to care about, or to have any interest in, you to do something for love of you. But here Shakespeare puts it out there on paper, directly in front of the young man: do this for love of me.

And so something has shifted. The tone most certainly has. The language is stronger, directer, bolder, and way more personal than it has been, and we now have a direct connection between the poet and the young man in the words themselves. And this is after all our approach: to listen to the words and find out what they themselves tell us.

And most fortuitously, fairly soon they will tell us a good deal more...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!