Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day?

|

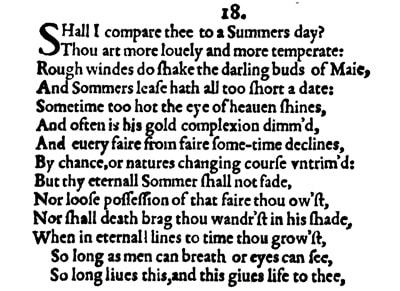

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer's lease hath all too short a date. Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimmed, And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature's changing course untrimmed. But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou owst, Nor shall Death brag thou wandrest in his shade When in eternal lines to time thou growst: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. |

|

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

|

Shall I compare you to a summer's day?

|

|

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

|

You are more lovely and more tempered or moderate and therefore more mild-mannered, more pleasing in your moods and in your emotional 'weather' than a summer day:

|

|

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

|

The lovely early blossom buds of an early summer day in May get shaken by rough winds...

|

|

And summer's lease hath all too short a date;

|

...and summer itself is all too short: 'date' here is an expiration date and so a lease that has a short date is a short lease.

|

|

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

|

Sometimes the sun – 'the eye of heaven' – shines too hot...

|

|

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

|

...and also often the golden face of the sun is obscured, such as by clouds for example...

|

|

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

|

...and everything that is beautiful will at some point lose this beauty...

|

|

By chance or nature's changing course untrimmed.

|

...cut down to its unadorned bare or barren state of old age by the vagaries of chance and accident, or simply by the ever-changing weather and seasons.

Something that is 'trimmed' is decorated, so a summer day is 'trimmed' with beautiful flowers, for example, whereas once it has been 'untrimmed' then these adornments have been taken away, as happens to every summer day and to every living thing eventually through the passing of time and the events that occur in our lives. |

|

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

|

But your summer will be eternal, it will not fade and thus come to an end...

|

|

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owst,

|

...nor will it – your eternal summer and therefore by extension you – lose that beauty which you own.

Note that 'owst' does not mean something that you owe, but something that you own, it's a contraction of 'ownest'. |

|

Nor shall death brag thou wandrest in his shade

|

Nor shall death – who is again here personified – ever be able to brag or boast that he has you in his shade, meaning that he, death, owns you because you are walking behind him – in his shadow – towards the valley of the dead...

|

|

When in eternal lines to time thou growst:

|

...when you grow towards the future – time – in the eternal lines of my verse, because:

|

|

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

|

for as long as men – for which read all human beings – are alive on this planet and therefore able to breathe and their eyes can see and are therefore able to read...

|

|

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

|

...this sonnet here that I have written for you will live and it is this sonnet that makes you live forever.

|

One of the most famous sonnets in the canon, Sonnet 18 bursts onto the scene with an energy, confidence, and message all of its own, setting the tone for a whole new kind of relationship and putting the poetry itself centre stage. It is one of the easiest to understand – which may in parts account for its immense popularity – and it is utterly delightful in its unabashed affirmation of life.

Gone is any attempt at making the young man marry to prolong his existence, to preserve his beauty, or to assure the continuation of his lineage. Some editors detect in the last line of the last quatrain a reference to the genealogical line, when I, the poet, say to the young man: "Nor shall death brag thou wandrest in his shade / When in eternal lines to time thou growst," but even that is at best spurious, as it is much more likely that I here simply refer to what I'm about to make so abundantly clear: these lines of poetry are what keep you alive in the minds and hearts of future generations.

This sonnet is a nearly direct declaration of love to, yes, its recipient, but even more so and much more directly to poetry itself, and what's more: it turns itself into a self-fulfilling prophecy, because when I conclude it with: "So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee." I tell no lie: we may not know for certain whom this sonnet is addressed to – although as you are aware if you've been following this excursion, we have been getting and will continue to receive some strong pointers – but whoever this person is, they exist vivid and strong in our imagination and they intrigue us to the point where we do ask – and almost have to ask – the question that so pushes itself to the fore now. And it is not so much a question as a bundle of questions which are all interwoven and which all appear in an instant together:

- Is this sonnet a 'real' communication to a 'real' person? Should we read it as something I, the poet, have written to an actual recipient or could it not be that it is simply an exercise in gorgeous poetry making? We have more or less answered this in the Introduction and been accepting the whole series so far as 'real': poetry written to a purpose to a real person, and there really is no reason to suddenly now assume that this here changes.

– If it is a real person, is it necessarily, as most people believe, still a man we are talking to, and is it necessarily the same man as the previous 17 sonnets? About this we talked a bit when looking at Sonnet 17, and there we observed a maybe not strictly linear but nevertheless clearly traceable trajectory these sonnets appear to be on. And so while it is possible that Sonnet 18 might have slipped into the collection here completely out of place, it doesn't look or sound it. At all. It sounds like it is exactly where it belongs, at the point in the relationship where I, the poet, give up on my task of trying to convince the young man to marry and have children, and instead pick up directly on what I said at the end of Sonnet 17, where I offered him two ways of perpetuating his existence: in his child and in my rhyme. Sonnet 18 now makes this second option the one that counts: the progression fits entirely. And if the recipient of this sonnet is the same person as the previous ones, then this does make him by necessity a young man, absolutely.

And this 'trajectory' of which we've spoken a few times now, this is not insignificant: if we not only look back at how this sonnet connects with the previous ones directly, but also forward to what I am about to say to the young man about himself, and his appearance, in Sonnet 20 and, before then in Sonnet 19, how I once again reiterate how my poetry can do the job I have previously ascribed to an offspring, namely allow this young man to conquer time and to live on throughout the ages, then almost any doubt as to the role this sonnet plays and whom it speaks to or why becomes effectively obsolete. Here as elsewhere I say 'almost' because there is a residual amount of doubt, always: we simply do not have proof positive about anything, but we have the words and the words give us such clear indicators now that it seems all but obtuse to still wonder, 'yes, but is it real?' or 'yes, but is it really the same person?' or even 'yes, but is it really a "Fair Youth" – a beautiful young man?' The reason we have over the last four hundred years widely and largely formed the opinion that it is is that very clearly it is.

And if this is correct, if it is real and if it is the same person and if that same person is, as we have reason to believe, a young English nobleman of high social status, who is obstinate in his refusal to marry, who is either a first-born or an only son, who bears a striking resemblance to his mother, and no longer has his father, then William Shakespeare here does something truly extraordinary. Because whoever this young man is, and our shortlist is by now really quite short, as we shortly shall discover, I, the poet, am now putting on paper and as far as anyone can tell telling this man that I am infatuated with him, that to me he is lovelier than a summer's day and that it is through me, none other, that he will live forever. That is, if nothing else, extraordinarily bold. And it presents us, as we proceed, with an entirely new question: what does the young man make of this?

Can we even assume, as we do, that he gets to read these lines? Or is this something that William Shakespeare, who as we have noted early on must by now be approaching thirty at least, like a teenager writes in his bedroom and keeps there in his drawer, as an unspoken fantasy?

We can't answer these questions yet, because our approach is to go by the words and what the words tell us alone, or almost alone, and the words don't give us any clue. Yet. But the 'yet', you will be glad to know, as so often before, is operational here: we will get very clear pointers on this too before too long.

And, indeed, in amongst all these truly fascinating questions and considerations about the person whom this poem might be addressed to, let's not ignore these words; let's let them actually speak to us: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" – For us this may sound like a nice little phrase that is probably also a poetic commonplace: something that poets routinely say or ask. And it clearly is: other poets in their poems will have likened someone they adore to a summer day. But put yourself into the England of around 1593: we have spoken before about how cold and bleak winter can be. Not only because there is no central heating, no electric light, no double glazing or contemporary construction and insulation materials, let alone textiles, but England, like much of Europe and indeed many other parts of the world, was then still going through what's known as the Little Ice Age, so winters were harsh and long.

What is particularly hard for us to imagine though is just how drab and dreary and colourless much of the dark season was. We are used to our world being illuminated and filled with colours all year round: we have brightly coloured clothes, we have gadgets and furniture in all kinds of colours, we have printed posters and brightly painted walls, and we spend much of our day looking at super-high definition screens and displays that show us everything in richly saturated spectra. In Shakespeare's day, other than for the exceptionally rich, colour did not feature in many people's lives for much of the year. The reason the rich wore colourful clothing was precisely because it was so expensive and thus so set them apart. Your ordinary person's winter day played out in shades of brown and beige and sooty grey.

So a summer's day, when it finally came, was a glorious thing. The fact that it did so with its darling buds apparently in May may on the one hand have to with the calendar in use at the time being out of synch with ours, which it was by ten days, since England continued using the Julian calendar long after catholic Europe adopted the corrected Gregorian calendar, or with a degree of poetic licence that allows Shakespeare to mingle signs of spring with those of summer, or indeed both.

The point being this: a summer's day is as good as it gets. A beautiful summer's day is the best. So if I say that you are better than that, then you are really rather amazing. Of course, Shakespeare actually qualifies his comparison and lists several ways in which even a summer day may well be imperfect. But here, as elsewhere, it may be kindest, most generous, and therefore probably best if we don't dwell too heavily on logic. This is poetry after all and not an exercise in mathematical thinking. Because, as also might be pointed out, what differentiates the beautiful young man here from the beautiful summer's day is not that only he can be eulogised in eternally lasting lines of poetry, but that this is what the poet chooses to do. If he felt like it, Shakespeare could probably write timeless poetry to and about a summer day of unparalleled beauty, and it would thus then last and persist in our collective conscious as much as the young man does.

What surely matters most though is the simple and boundless joy of this Shakespearean summer salutation: I use this sonnet regularly in my university teaching as the go to example for our need for poetry itself. Because after all: why write poetry? Why not just say what you want to say and be done with it? We write poetry because we have to. If we hadn't evolved as a species that needs to celebrate, record, solemnise, reflect on, and reflect our existence in ways that we can feel us much as, if not more than, understand, then we would not have developed poetry. The same with music, the same with art, the same with dance, the same with any cultivated form of expression that makes us what we are: human. Poetry is quintessentially human. And so of course I can say to you: "you are very beautiful and mild-mannered too, and I say you will be so forever." But although the meaning, the semantics, is there, it doesn't really mean anything and it certainly doesn't do anything. But when I say to you: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate..." you cannot help but love me just a little just for that. Just for the tingle it sends down your spine, for the rhythm and the cadence, for the gorgeousness, for the sheer pleasure, of the sound.

In the 1989 film classic Dead Poets Society, screenwriter Tom Schulman has his boys' boarding school teacher John Keating ask his teenage charges: "Why do men write poetry?" only to answer the question himself: "to woo women!" This is undoubtedly true, and true too of men who woo other men and of women who woo women or men, or of people of any or no particular gender who want someone in the world to love them. And the poetry of these sonnets now has just shifted into this greatest of human experiences: love.

Fear not though: it will not remain here for long, it will range and expound and explore, it will bring us face to face with almost any human emotion we can remember ever feeling ourselves, but this is the real start. If you are only joining our journey now, you are not too late: you may have missed the prelude of the 17 Procreation Sonnets– which of course you can always go back to and catch up on: it's there to be listened to any time you like – but the real, the exhilarating, the profound encounter with William Shakespeare through his sonnets starts right here, right now, with Sonnet 18.

Gone is any attempt at making the young man marry to prolong his existence, to preserve his beauty, or to assure the continuation of his lineage. Some editors detect in the last line of the last quatrain a reference to the genealogical line, when I, the poet, say to the young man: "Nor shall death brag thou wandrest in his shade / When in eternal lines to time thou growst," but even that is at best spurious, as it is much more likely that I here simply refer to what I'm about to make so abundantly clear: these lines of poetry are what keep you alive in the minds and hearts of future generations.

This sonnet is a nearly direct declaration of love to, yes, its recipient, but even more so and much more directly to poetry itself, and what's more: it turns itself into a self-fulfilling prophecy, because when I conclude it with: "So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee." I tell no lie: we may not know for certain whom this sonnet is addressed to – although as you are aware if you've been following this excursion, we have been getting and will continue to receive some strong pointers – but whoever this person is, they exist vivid and strong in our imagination and they intrigue us to the point where we do ask – and almost have to ask – the question that so pushes itself to the fore now. And it is not so much a question as a bundle of questions which are all interwoven and which all appear in an instant together:

- Is this sonnet a 'real' communication to a 'real' person? Should we read it as something I, the poet, have written to an actual recipient or could it not be that it is simply an exercise in gorgeous poetry making? We have more or less answered this in the Introduction and been accepting the whole series so far as 'real': poetry written to a purpose to a real person, and there really is no reason to suddenly now assume that this here changes.

– If it is a real person, is it necessarily, as most people believe, still a man we are talking to, and is it necessarily the same man as the previous 17 sonnets? About this we talked a bit when looking at Sonnet 17, and there we observed a maybe not strictly linear but nevertheless clearly traceable trajectory these sonnets appear to be on. And so while it is possible that Sonnet 18 might have slipped into the collection here completely out of place, it doesn't look or sound it. At all. It sounds like it is exactly where it belongs, at the point in the relationship where I, the poet, give up on my task of trying to convince the young man to marry and have children, and instead pick up directly on what I said at the end of Sonnet 17, where I offered him two ways of perpetuating his existence: in his child and in my rhyme. Sonnet 18 now makes this second option the one that counts: the progression fits entirely. And if the recipient of this sonnet is the same person as the previous ones, then this does make him by necessity a young man, absolutely.

And this 'trajectory' of which we've spoken a few times now, this is not insignificant: if we not only look back at how this sonnet connects with the previous ones directly, but also forward to what I am about to say to the young man about himself, and his appearance, in Sonnet 20 and, before then in Sonnet 19, how I once again reiterate how my poetry can do the job I have previously ascribed to an offspring, namely allow this young man to conquer time and to live on throughout the ages, then almost any doubt as to the role this sonnet plays and whom it speaks to or why becomes effectively obsolete. Here as elsewhere I say 'almost' because there is a residual amount of doubt, always: we simply do not have proof positive about anything, but we have the words and the words give us such clear indicators now that it seems all but obtuse to still wonder, 'yes, but is it real?' or 'yes, but is it really the same person?' or even 'yes, but is it really a "Fair Youth" – a beautiful young man?' The reason we have over the last four hundred years widely and largely formed the opinion that it is is that very clearly it is.

And if this is correct, if it is real and if it is the same person and if that same person is, as we have reason to believe, a young English nobleman of high social status, who is obstinate in his refusal to marry, who is either a first-born or an only son, who bears a striking resemblance to his mother, and no longer has his father, then William Shakespeare here does something truly extraordinary. Because whoever this young man is, and our shortlist is by now really quite short, as we shortly shall discover, I, the poet, am now putting on paper and as far as anyone can tell telling this man that I am infatuated with him, that to me he is lovelier than a summer's day and that it is through me, none other, that he will live forever. That is, if nothing else, extraordinarily bold. And it presents us, as we proceed, with an entirely new question: what does the young man make of this?

Can we even assume, as we do, that he gets to read these lines? Or is this something that William Shakespeare, who as we have noted early on must by now be approaching thirty at least, like a teenager writes in his bedroom and keeps there in his drawer, as an unspoken fantasy?

We can't answer these questions yet, because our approach is to go by the words and what the words tell us alone, or almost alone, and the words don't give us any clue. Yet. But the 'yet', you will be glad to know, as so often before, is operational here: we will get very clear pointers on this too before too long.

And, indeed, in amongst all these truly fascinating questions and considerations about the person whom this poem might be addressed to, let's not ignore these words; let's let them actually speak to us: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" – For us this may sound like a nice little phrase that is probably also a poetic commonplace: something that poets routinely say or ask. And it clearly is: other poets in their poems will have likened someone they adore to a summer day. But put yourself into the England of around 1593: we have spoken before about how cold and bleak winter can be. Not only because there is no central heating, no electric light, no double glazing or contemporary construction and insulation materials, let alone textiles, but England, like much of Europe and indeed many other parts of the world, was then still going through what's known as the Little Ice Age, so winters were harsh and long.

What is particularly hard for us to imagine though is just how drab and dreary and colourless much of the dark season was. We are used to our world being illuminated and filled with colours all year round: we have brightly coloured clothes, we have gadgets and furniture in all kinds of colours, we have printed posters and brightly painted walls, and we spend much of our day looking at super-high definition screens and displays that show us everything in richly saturated spectra. In Shakespeare's day, other than for the exceptionally rich, colour did not feature in many people's lives for much of the year. The reason the rich wore colourful clothing was precisely because it was so expensive and thus so set them apart. Your ordinary person's winter day played out in shades of brown and beige and sooty grey.

So a summer's day, when it finally came, was a glorious thing. The fact that it did so with its darling buds apparently in May may on the one hand have to with the calendar in use at the time being out of synch with ours, which it was by ten days, since England continued using the Julian calendar long after catholic Europe adopted the corrected Gregorian calendar, or with a degree of poetic licence that allows Shakespeare to mingle signs of spring with those of summer, or indeed both.

The point being this: a summer's day is as good as it gets. A beautiful summer's day is the best. So if I say that you are better than that, then you are really rather amazing. Of course, Shakespeare actually qualifies his comparison and lists several ways in which even a summer day may well be imperfect. But here, as elsewhere, it may be kindest, most generous, and therefore probably best if we don't dwell too heavily on logic. This is poetry after all and not an exercise in mathematical thinking. Because, as also might be pointed out, what differentiates the beautiful young man here from the beautiful summer's day is not that only he can be eulogised in eternally lasting lines of poetry, but that this is what the poet chooses to do. If he felt like it, Shakespeare could probably write timeless poetry to and about a summer day of unparalleled beauty, and it would thus then last and persist in our collective conscious as much as the young man does.

What surely matters most though is the simple and boundless joy of this Shakespearean summer salutation: I use this sonnet regularly in my university teaching as the go to example for our need for poetry itself. Because after all: why write poetry? Why not just say what you want to say and be done with it? We write poetry because we have to. If we hadn't evolved as a species that needs to celebrate, record, solemnise, reflect on, and reflect our existence in ways that we can feel us much as, if not more than, understand, then we would not have developed poetry. The same with music, the same with art, the same with dance, the same with any cultivated form of expression that makes us what we are: human. Poetry is quintessentially human. And so of course I can say to you: "you are very beautiful and mild-mannered too, and I say you will be so forever." But although the meaning, the semantics, is there, it doesn't really mean anything and it certainly doesn't do anything. But when I say to you: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate..." you cannot help but love me just a little just for that. Just for the tingle it sends down your spine, for the rhythm and the cadence, for the gorgeousness, for the sheer pleasure, of the sound.

In the 1989 film classic Dead Poets Society, screenwriter Tom Schulman has his boys' boarding school teacher John Keating ask his teenage charges: "Why do men write poetry?" only to answer the question himself: "to woo women!" This is undoubtedly true, and true too of men who woo other men and of women who woo women or men, or of people of any or no particular gender who want someone in the world to love them. And the poetry of these sonnets now has just shifted into this greatest of human experiences: love.

Fear not though: it will not remain here for long, it will range and expound and explore, it will bring us face to face with almost any human emotion we can remember ever feeling ourselves, but this is the real start. If you are only joining our journey now, you are not too late: you may have missed the prelude of the 17 Procreation Sonnets– which of course you can always go back to and catch up on: it's there to be listened to any time you like – but the real, the exhilarating, the profound encounter with William Shakespeare through his sonnets starts right here, right now, with Sonnet 18.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!