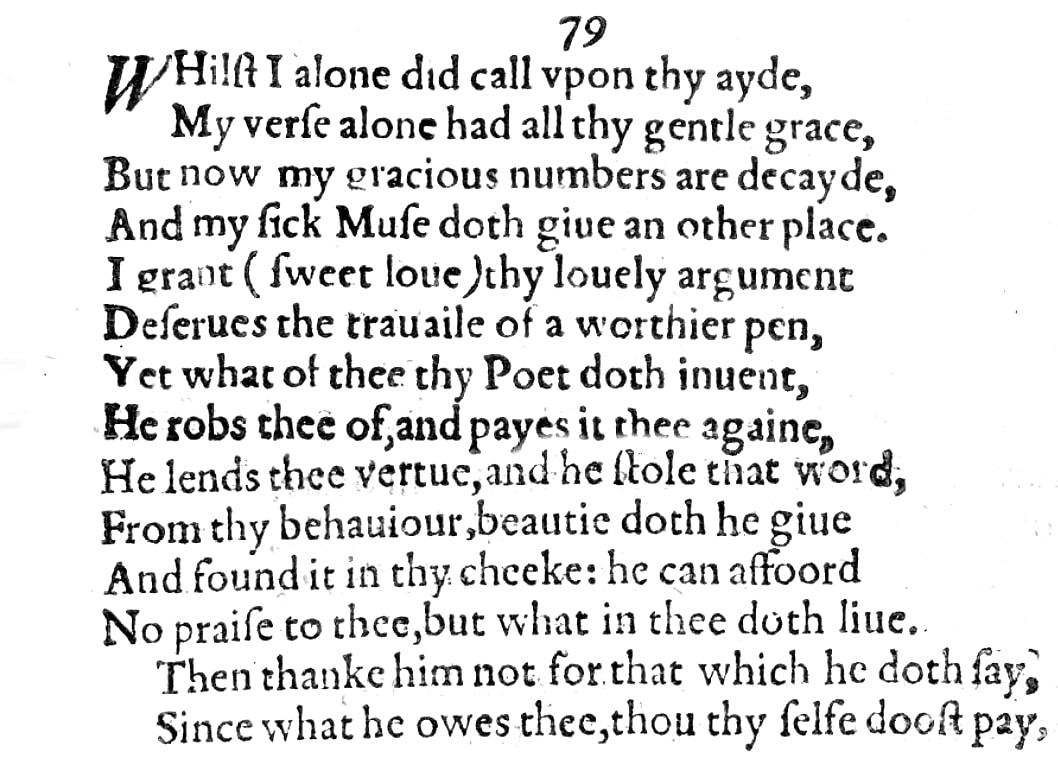

Sonnet 79: Whilst I Alone Did Call Upon Thy Aid

|

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid,

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace, But now my gracious numbers are decayed And my sick Muse doth give another place. I grant, sweet love, thy lovely argument Deserves the travail of a worthier pen, Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent, He robs thee of, and pays it thee again. He lends thee virtue, and he stole that word From thy behaviour; beauty doth he give And found it in thy cheek: he can afford No praise to thee but what in thee doth live. Then thank him not for that which he doth say, Since what he owes thee, thou thyself dost pay. |

|

Whilst I alone did call upon thy aid,

My verse alone had all thy gentle grace, |

The poem, though not strictly paired with Sonnet 78, spins the thought developed there further by saying, while I was the only poet who called upon your aid and therefore received the "fair assistance" mentioned in Sonnet 78, it was my poetry alone that was infused with your gentleness, your grace, your beauty.

As in Sonnet 78, there may be more than a hint of wordplay at work here with 'gentle' and 'grace'. We recall that in Sonnet 41, which needed to absolve the young man of his guilt for seducing Shakespeare's own mistress, Shakespeare excused him by arguing Gentle thou art, and therefore to be won, Beauteous thou art, therefore to be assailed and looking back over this very recently in the Halfway Point Summary, we recalled that this 'gentle' may be a reference not merely to the young man's mild-mannered loveliness, but also to his standing as a gentleman, in the sense of a wealthy man of high birth. This may be the case here too, and the prevalence in this poem, as well as in Sonnet 78, of the concept 'grace' points strongly to some significance: 'grace', 'graces', 'graced', and 'gracious' feature no less than five times across these two poems, which can hardly be considered a coincidence. |

|

But now my gracious numbers are decayed

And my sick Muse doth give another place. |

But now – implied is now that I am no longer the only poet who calls upon and receives your aid – my formerly gracious verses – gracious because imbued with your grace – have decayed and my inspiration, which is sick because it no longer is able to come up with such gracious poetry, makes way to someone else.

In Sonnet 17, which you may recall casts something of a bridge from the Procreation Sonnets, which it is still part of, to the main body of the Fair Youth Sonnets, starting with Sonnet 18, William Shakespeare told the young man: If I could write the beauty of your eyes And in fresh numbers number all your graces 'Numbers' there as here refers to the lines of poetry themselves, since it stands as a synonym for 'metre', as in the metre of the verse. 'Muse', throughout these sonnets, is used by Shakespeare to mean both, the 'inspiration', the person who takes on the role of the Greek goddess and enables the art of poetry, and the poet himself, but this is a rare instance where both meanings overlap and appear to be applied at the same time, because it is of course Shakespeare himself who makes place for another poet. This is also the first time in this group that make up the Rival Poet Sonnets that Shakespeare moves from the generality of other poets that characterised Sonnet 78, to a single other who is taking his place. |

|

I grant, sweet love, thy lovely argument

Deserves the travail of a worthier pen, |

I admit, sweet love, that the lovely argument that you yourself represent merits the efforts of a better poet.

'Argument' with this meaning we have come across before, it is the content and substance of rhetoric, in the classical and Renaissance sense of an artfully constructed speech or piece of poetry. This sonnet too, then, like Sonnet 78, either deliberately or accidentally, references Sonnet 38: How can my Muse want subject to invent, While thou dost breathe that pourst into my verse Thine own sweet argument, too excellent For every vulgar paper to rehearse. 'Travail', we noted on previous occasions, can mean both 'travel' and, derived directly from the French travail, 'work'. The two often go together, since travelling in Shakespeare's day is rarely done for pleasure and hardly ever amounts to one, but here the meaning very clearly is 'effort' or 'work'. And 'pen' as in Sonnet 78 stands in for 'poet'. And if we had our attention drawn to 'grace' earlier, then it may – or may not – be significant, that the better poet here is described specifically as 'worthier'. This may simply refer to his worth as a skilled writer, and therefore to his status as a professional. It does also invite, however, a connotation of social status, as in, again, a worthy gentleman, for instance, a member of the nobility. If that is intended, rather than incidental, the following lines become particularly striking, deploying, as they do a language of theft: |

|

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent,

He robs the of, and pays it thee again. |

And yet, what your poet writes of you, he actually first of all steals from you and then gives it back to you.

'Invent' similarly – and indeed as in Sonnet 38 – is here used in the classical rhetorical sense of finding the right arguments for your topic. We discussed this very recently too in the context of Sonnet 76, so here just a brief reminder, it does not mean to 'make up' or 'create out of nothing' but to search and find good points to make in a piece of rhetoric, such as a speech or a poem. |

|

He lends thee virtue, and he stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty doth he give And found it in thy cheek: |

And here are a couple of examples of what the poet might thus find and then write down about you: he talks about virtue and by talking about it lends you this characteristic, but he actually stole this word from you by looking at your behaviour, which is virtuous. And in fact, in Elizabethan English, 'behaviour' has positive connotations, as in 'comportment', as in 'good behaviour'. We, by contrast, tend to talk about 'behaviour' when it isn't particularly good:' their behaviour was outrageous', for example.

Similarly, he says you are beautiful, but of course he has found the beauty of which he speaks in you; and 'cheek' here as elsewhere standing for 'face'. What to us – knowing the young man as we do by now – feels at least somewhat incongruous is the idea that the young man is virtuous. Several sonnets – we have mentioned them often, most recently in the Halfway Point Summary, so I will not go over them again right now – give us the impression that our poet's young lover is anything but a pinnacle of virtue as it is commonly understood. In fact, the last time we heard Shakespeare use the word behaviour in the context of the young man, in Sonnet 69, the people who looked at this came to the conclusion – the positive connotations of the word 'behaviour' just mentioned notwithstanding – that the outward beauty of his looks was accompanied by the foul stench of his character. But this should not disconcert us too much and it certainly cannot be taken as an indication that perhaps we are talking to a different young man. What this is an indication of is that William Shakespeare is in fear of losing his young lover, quite possibly his patron, and here blatantly flatters him to win him back; and of course Sonnet 69 itself is immediately followed by Sonnet 70 which starts with the line, "That thou are blamed shall not be thy defect," and occupies itself over the next 13 lines with explaining why the young man is just being slandered by those who are envious of him. There, too, we felt we could not quite believe our otherwise mostly, notably sincere and honest poet every word he was saying, and it may be for exactly the same reason... |

|

he can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live. |

He, your poet, can offer up, give, present to you no praise other than what lives in you and what he therefore is able to take from you. In other words, everything your poet writes about you can only ever come from you.

This quatrain presents a stylistic oddity that does occur elsewhere, but rarely. Shakespeare breaks his sentence mid-line and cascades his enumeration of offerings the poet cannot himself afford rather 'ungraciously' over his metre: he is almost showing what is happening to his poetry because of this other poet having nudged his way into his position, and he also, in doing so – rather skilfully, of course – lends the list of charges against his rival a breathless urgency. |

|

Then thank him not for that which he doth say,

For what he owes thee, thou thyself dost pay. |

And so: don't thank him, your poet, for what he says and writes about you, because what he owes you – implied is in return for your attention, possibly your patronage and financial support, possibly your general favour – you yourself are paying for by giving him everything he uses and then returns to you in the form of his poetry.

|

With Sonnet 79, William Shakespeare continues his lament, begun with Sonnet 78, that he no longer enjoys the exclusive privilege of writing poetry to and for his young lover, constructing an – objectively speaking fairly tenuous – argument why the young man should not be overly grateful to this Rival Poet for his efforts. With a transactional tone taking over the second half of the sonnet, it pushes our perception further towards a possibility that Shakespeare is losing not only the appreciation and affection of his young lover, but also his patronage, which, if the case, would possibly have serious implications in terms of his financial and social status.

What makes the argument of Sonnet 79 tenuous are fundamentally two things. Firstly, the premise itself:

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent

He robs thee of and pays it thee again.

With our contemporary understanding of the word 'invent' me might feel tempted to say, fair enough: a poet should be capable of doing more than talk about his subject in terms of what he finds there. It may be the case, as Gertrude Stein put it roughly 320 years after Shakespeare wrote his sonnet that, "a rose is a rose is a rose," but for a Renaissance poet that would clearly not do: he should have the wherewithal to come up with more interesting insights and – here our definition of the term 'invent' would come into play – take his poetic licence and be creative. Effectively make things up that may not be strictly, factually true but that are enjoyable to hear and to read and bring out the character of whom or what is being talked about.

But as we have seen, 'invent' here as elsewhere in these sonnets takes its meaning from the ancient art of rhetoric where it precisely does not describe the making up of things, but the search for and finding of good arguments to convince the reader or listener of the point you are making. And this, when eulogising a person, can only truthfully happen by looking at who and what this person is and then talking about it in a skilled way. Shakespeare himself is adamant that that's what he does: be truthful in his language. Interestingly, he doesn't do so in this poem, but in Sonnet 21, for example, he insists:

O let me, true in love, but truly write,

And then, believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother's child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air.

Let them say more that like of hearsay well,

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

And in Sonnet 82 he will make this claim even stronger, saying, as we shall see:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In plain true words, by thy true-telling friend.

So setting out to argue, as this sonnet appears to be doing, that simply taking your subject – here the young man – and talking about the qualities you find in him as they are is not deserving of much gratitude, since your subject is effectively providing you with all the material you then use to write about them, seems somewhat disingenuous.

Shakespeare, we have observed before, and with greatest love, respect, and admiration, is master of many things, among them most things poetic, but when it comes to logic, he struggles a little, our Will. And logic trips him up here too with the second flaw on display in his thinking in this sonnet which is simply this: everything he says about his rival in this poem also applies to him: the argument of this sonnet does not change if, instead of talking about the Rival Poet – whoever that may be – we insert William Shakespeare himself into the role of the writer.

If I were a self-critical poet being strict and maybe a bit harsh in my assessment of my own work, I could easily put down:

I lend thee virtue, and I stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty do I give

And found it in thy cheek: I can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live.

Then thank me not for that which I do say,

Since what I owe thee, thou thyself dost pay.

And in fact, Shakespeare himself says something very similar to this in Sonnet 38:

O give thyself the thanks if ought in me

Worthy perusal stand against thy sight,

For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee,

When thou thyself dost give invention light?

A poem he closes with:

If my slight Muse do please these curious days,

The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.

The upshot of which pretty much is: what I have written I have only been able to write because you provide me with all the inspiration and material that then goes into my poetry. And of course in the sonnet just preceding this one, Sonnet 78, Shakespeare also says something to this effect when he speaks of his poetry:

Whose influence is thine and borne of thee.

And so if Shakespeare wants to use this sonnet here now to tell his young man that he should not be paying too much attention and certainly not expend any excessive gratitude on his poet, then he really is including himself in the entity 'poet', because this sonnet certainly makes no argument for his own poetry being in any way different or superior, unlike Sonnet 78, perhaps, which at the very least distinguishes Shakespeare's from the other poets' or poet's offerings by saying that it in fact is exclusive to the young man.

The other especially telling aspect to Sonnet 79 is one we mentioned very briefly in the introductory paragraph. We had been wondering with Sonnet 78 already, whether Shakespeare was worrying not only about losing his young lover's affection and estimation, but also his patronage, and if so to what extent this was the case.

Sonnet 79 provides no clear answer to this question any more than Sonnet 78 was able to, but what this sonnet does do is skew the language much more towards business, finance, and transaction. When Sonnet 78 emphasised learning and elevation in both education and status, Sonnet 79 talks about what the poet 'pays', 'lends', 'can afford', and 'owes'. And all of this, the young man in turn does 'pay'. And of course we can't ignore the insinuation of improbity: the poet here 'robs'. He not only 'found', he also 'stole' from the young man to assemble his verse.

This brings together two fascinating strands of thought. The first one is what may be a wittingly or unwittingly implied contrast between Shakespeare and his rival, in that the only time so far that we have heard Shakespeare say of himself that he had to take something from the young man even if it wasn't voluntarily forthcoming was in Sonnet 75, where he found himself

Possessing or pursuing no delight

Save what is had or must from you be took.

Other than that, the stance was very much one of gratefully receiving the munificence of his benefactor in love who may or may not also be a benefactor in finance. The rival here is portrayed – or perhaps caricatured might be more accurate an expression – as someone who gets their material by stealth. I want to stress that we cannot be sure whether this contrast is what Shakespeare here means to highlight. If so, he is not doing it explicitly.

And the other thought stems from the transactional nature of these lines in itself. This, I cannot readily believe to be a pure accident or coincidence.

Shakespeare is working – it is worth bringing this back to our mind – in an unequal world of great interdependencies. Concepts we take for granted, such as 'freedom of expression', 'equal rights', and even 'democracy' were not only not much known or talked about, they were positively anathema to an orderly running of Elizabethan society.

You were born into a social class and in principle stayed there. Your betters were those who were born into a class and status above you, and unless you were in the lowest order of society you almost always had someone beneath you who did things for you. Good people were those who played their role in society responsibly and charitably, bad people were those who exploited or cruelly treated others and those who broke out of their strata to upset the order of things. If you were considered to be dangerous, you could be done away with without much do or leave, and if it served the state to brand you a traitor, your punishment would be deliberately cruel and gruesome, to warn off others. Because of the great threat to the protestant Queen from her catholic enemies, there were spies everywhere and you had to be exceptionally careful what you said to whom if you didn't agree with the government of the day which was run in a near totalitarian style on behalf of the monarch.

In such a world, a poet is one thing, a young aristocrat is another. Obtaining the patronage of a rich nobleman – be he young or old, handsome or no – was not a mere luxury, it was for many poets essential, if they wanted to make a decent living from their art. Losing such patronage could spell disaster, or, if not disaster, sudden and possibly lasting hardship. Also, nothing moved or worked in isolation. Society – the society that mattered – was confined to a relatively small number of people who knew each other and of each other and who were in some cases related to each other by blood ties or connected through tightly knit networks of kinship and loyalty.

And so if our poet, William Shakespeare is at this point in his life in a situation where he either already enjoys or was about to get the patronage – as in financial and public support – of a young man who also happens to have been his lover for some time now – long enough at any rate to have been writing many sonnets to him, as he told us himself just recently in Sonnets 76 and 78 – and this young man now is making signs of adopting someone else as their poet of choice, then that is a genuinely serious blow on several levels all at once, and one that, no matter how skilled a wordsmith you are, is exceptionally difficult to handle. Because what can you say? You can't afford to offend your young man, and there are stringent limits as to how honest you can really be in expressing your own dejection. It would be tough enough if it were purely about business. But for Shakespeare it very clearly isn't.

So this playing through the vocabulary of financial transactions and mingling it with the vocabulary of property crime is one way a man who is not only in love but also in a position of dependency on his lover can signal to him and maybe to the world, should the world ever get to read or hear this, that this is a calamity that cannot be just quietly acquiesced to.

And as if the emotional heartache of seeing your lover receive the poetry of another person and apparently – this much is certainly implied – lending it and this other person favourable attention, and quite possibly experiencing an attendant economic setback of your work no longer being championed as it had been by your lover, as if that weren't enough, a sexual dimension is about to add itself to the picture with the spectacularly melodramatic and at the same time deliciously mischievous, frivolous Sonnet 80...

What makes the argument of Sonnet 79 tenuous are fundamentally two things. Firstly, the premise itself:

Yet what of thee thy poet doth invent

He robs thee of and pays it thee again.

With our contemporary understanding of the word 'invent' me might feel tempted to say, fair enough: a poet should be capable of doing more than talk about his subject in terms of what he finds there. It may be the case, as Gertrude Stein put it roughly 320 years after Shakespeare wrote his sonnet that, "a rose is a rose is a rose," but for a Renaissance poet that would clearly not do: he should have the wherewithal to come up with more interesting insights and – here our definition of the term 'invent' would come into play – take his poetic licence and be creative. Effectively make things up that may not be strictly, factually true but that are enjoyable to hear and to read and bring out the character of whom or what is being talked about.

But as we have seen, 'invent' here as elsewhere in these sonnets takes its meaning from the ancient art of rhetoric where it precisely does not describe the making up of things, but the search for and finding of good arguments to convince the reader or listener of the point you are making. And this, when eulogising a person, can only truthfully happen by looking at who and what this person is and then talking about it in a skilled way. Shakespeare himself is adamant that that's what he does: be truthful in his language. Interestingly, he doesn't do so in this poem, but in Sonnet 21, for example, he insists:

O let me, true in love, but truly write,

And then, believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother's child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air.

Let them say more that like of hearsay well,

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

And in Sonnet 82 he will make this claim even stronger, saying, as we shall see:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In plain true words, by thy true-telling friend.

So setting out to argue, as this sonnet appears to be doing, that simply taking your subject – here the young man – and talking about the qualities you find in him as they are is not deserving of much gratitude, since your subject is effectively providing you with all the material you then use to write about them, seems somewhat disingenuous.

Shakespeare, we have observed before, and with greatest love, respect, and admiration, is master of many things, among them most things poetic, but when it comes to logic, he struggles a little, our Will. And logic trips him up here too with the second flaw on display in his thinking in this sonnet which is simply this: everything he says about his rival in this poem also applies to him: the argument of this sonnet does not change if, instead of talking about the Rival Poet – whoever that may be – we insert William Shakespeare himself into the role of the writer.

If I were a self-critical poet being strict and maybe a bit harsh in my assessment of my own work, I could easily put down:

I lend thee virtue, and I stole that word

From thy behaviour; beauty do I give

And found it in thy cheek: I can afford

No praise to thee but what in thee doth live.

Then thank me not for that which I do say,

Since what I owe thee, thou thyself dost pay.

And in fact, Shakespeare himself says something very similar to this in Sonnet 38:

O give thyself the thanks if ought in me

Worthy perusal stand against thy sight,

For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee,

When thou thyself dost give invention light?

A poem he closes with:

If my slight Muse do please these curious days,

The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.

The upshot of which pretty much is: what I have written I have only been able to write because you provide me with all the inspiration and material that then goes into my poetry. And of course in the sonnet just preceding this one, Sonnet 78, Shakespeare also says something to this effect when he speaks of his poetry:

Whose influence is thine and borne of thee.

And so if Shakespeare wants to use this sonnet here now to tell his young man that he should not be paying too much attention and certainly not expend any excessive gratitude on his poet, then he really is including himself in the entity 'poet', because this sonnet certainly makes no argument for his own poetry being in any way different or superior, unlike Sonnet 78, perhaps, which at the very least distinguishes Shakespeare's from the other poets' or poet's offerings by saying that it in fact is exclusive to the young man.

The other especially telling aspect to Sonnet 79 is one we mentioned very briefly in the introductory paragraph. We had been wondering with Sonnet 78 already, whether Shakespeare was worrying not only about losing his young lover's affection and estimation, but also his patronage, and if so to what extent this was the case.

Sonnet 79 provides no clear answer to this question any more than Sonnet 78 was able to, but what this sonnet does do is skew the language much more towards business, finance, and transaction. When Sonnet 78 emphasised learning and elevation in both education and status, Sonnet 79 talks about what the poet 'pays', 'lends', 'can afford', and 'owes'. And all of this, the young man in turn does 'pay'. And of course we can't ignore the insinuation of improbity: the poet here 'robs'. He not only 'found', he also 'stole' from the young man to assemble his verse.

This brings together two fascinating strands of thought. The first one is what may be a wittingly or unwittingly implied contrast between Shakespeare and his rival, in that the only time so far that we have heard Shakespeare say of himself that he had to take something from the young man even if it wasn't voluntarily forthcoming was in Sonnet 75, where he found himself

Possessing or pursuing no delight

Save what is had or must from you be took.

Other than that, the stance was very much one of gratefully receiving the munificence of his benefactor in love who may or may not also be a benefactor in finance. The rival here is portrayed – or perhaps caricatured might be more accurate an expression – as someone who gets their material by stealth. I want to stress that we cannot be sure whether this contrast is what Shakespeare here means to highlight. If so, he is not doing it explicitly.

And the other thought stems from the transactional nature of these lines in itself. This, I cannot readily believe to be a pure accident or coincidence.

Shakespeare is working – it is worth bringing this back to our mind – in an unequal world of great interdependencies. Concepts we take for granted, such as 'freedom of expression', 'equal rights', and even 'democracy' were not only not much known or talked about, they were positively anathema to an orderly running of Elizabethan society.

You were born into a social class and in principle stayed there. Your betters were those who were born into a class and status above you, and unless you were in the lowest order of society you almost always had someone beneath you who did things for you. Good people were those who played their role in society responsibly and charitably, bad people were those who exploited or cruelly treated others and those who broke out of their strata to upset the order of things. If you were considered to be dangerous, you could be done away with without much do or leave, and if it served the state to brand you a traitor, your punishment would be deliberately cruel and gruesome, to warn off others. Because of the great threat to the protestant Queen from her catholic enemies, there were spies everywhere and you had to be exceptionally careful what you said to whom if you didn't agree with the government of the day which was run in a near totalitarian style on behalf of the monarch.

In such a world, a poet is one thing, a young aristocrat is another. Obtaining the patronage of a rich nobleman – be he young or old, handsome or no – was not a mere luxury, it was for many poets essential, if they wanted to make a decent living from their art. Losing such patronage could spell disaster, or, if not disaster, sudden and possibly lasting hardship. Also, nothing moved or worked in isolation. Society – the society that mattered – was confined to a relatively small number of people who knew each other and of each other and who were in some cases related to each other by blood ties or connected through tightly knit networks of kinship and loyalty.

And so if our poet, William Shakespeare is at this point in his life in a situation where he either already enjoys or was about to get the patronage – as in financial and public support – of a young man who also happens to have been his lover for some time now – long enough at any rate to have been writing many sonnets to him, as he told us himself just recently in Sonnets 76 and 78 – and this young man now is making signs of adopting someone else as their poet of choice, then that is a genuinely serious blow on several levels all at once, and one that, no matter how skilled a wordsmith you are, is exceptionally difficult to handle. Because what can you say? You can't afford to offend your young man, and there are stringent limits as to how honest you can really be in expressing your own dejection. It would be tough enough if it were purely about business. But for Shakespeare it very clearly isn't.

So this playing through the vocabulary of financial transactions and mingling it with the vocabulary of property crime is one way a man who is not only in love but also in a position of dependency on his lover can signal to him and maybe to the world, should the world ever get to read or hear this, that this is a calamity that cannot be just quietly acquiesced to.

And as if the emotional heartache of seeing your lover receive the poetry of another person and apparently – this much is certainly implied – lending it and this other person favourable attention, and quite possibly experiencing an attendant economic setback of your work no longer being championed as it had been by your lover, as if that weren't enough, a sexual dimension is about to add itself to the picture with the spectacularly melodramatic and at the same time deliciously mischievous, frivolous Sonnet 80...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!