Sonnet 44: If the Dull Substance of My Flesh Were Thought

|

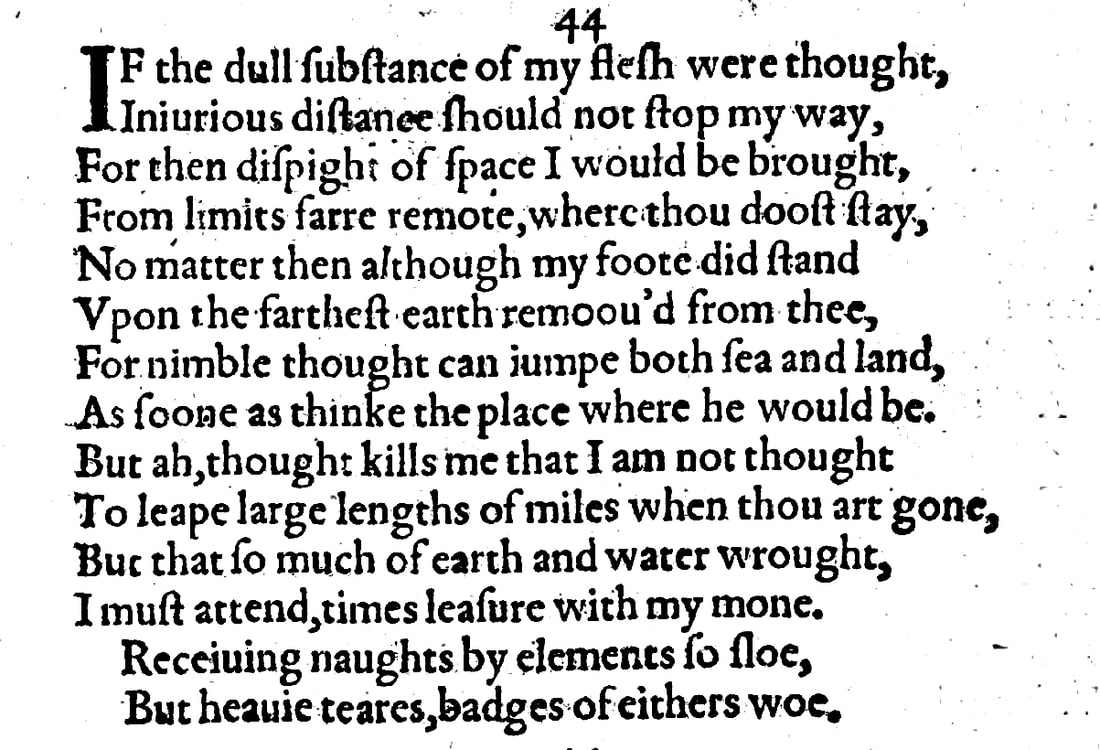

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought,

Injurious distance should not stop my way, For then, despite of space, I would be brought From limits far remote where thou dost stay. No matter then although my foot did stand Upon the farthest earth removed from thee, For nimble thought can jump both sea and land As soon as think the place where he would be. But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought To leap large lengths of miles when thou art gone, But that, so much of earth and water wrought, I must attend time's leisure with my moan, Receiving naught by elements so slow But heavy tears, badges of either's woe. |

|

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought,

|

If instead of heavy substance my body were made only of thought...

'Dull' is a particularly gratifying way of describing the poet's body at this point, because it has multiple meanings of 'slow', 'sluggish', 'inanimate', but also in the past more of 'bored', 'dispirited' and even 'numb'. All these may literally and metaphorically apply to someone who is away from his lover and missing him. |

|

Injurious distance should not stop my way,

|

...then the painful distance that lies between us would not be able to stop me.

Implied obviously is 'from coming to you', as is spelt out in a moment. And 'injurious' does carry the sense of somebody or something – here the given circumstances – intentionally wounding or harming the victim, here principally the poet and by extension therefore also his young lover, by keeping them apart. |

|

For then, despite of space, I would be brought

From limits far remote where thou dost stay. |

Because then – if my body were made of mere thought – in spite of the space that lies between us I would be able to come from the farthest regions of the earth to wherever you happen to be.

'Limits' are districts or regions, but the term underlines an extremity of space, possibly intended to invoke the poetic 'end of the world', which is reinforced in the next couplet: |

|

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee, |

It wouldn't matter then if I were standing on a piece of land that is farthest away from you...

|

|

For nimble thought can jump both sea and land

As soon as think the place where he would be. |

...because thought, which is immaterial and therefore nimble and lightning fast, can jump across sea and land as quickly as it thinks of the place where it wants to be, and any time it does so.

Thought here is mildly personified: neither the Quarto Edition nor the great majority of editors capitalise it, but it is referred to as 'he' in this sentence. |

|

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large lengths of miles when thou art gone, |

But ah, the thought kills me that I am not made merely of thought so I could leap across these long distances numbering many miles when you are away from me...

|

|

But that, so much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time's leisure with my moan, |

...but, being so much made of earth and water, I have to wait until time itself is ready to bring us back together, left here with my moans about this sad situation, which I now pour into this verse.

'Earth and water' refers to the four classical elements, earth, water, air, and fire, which were believed to make up all physical substances, including the human body. These are tied into the four temperaments, melancholic (analytical, pensive, tending towards pessimism, associated with earth), phlegmatic (relaxed, easy-going, possibly verging on complacent – water), sanguine (social, communicative, optimistic – air), and choleric (short-fused, irritable, tending to aggression – fire), which were used as compound personality types to describe the basic nature of people, not dissimilar in ambition to today's Myers-Briggs categories. This also anticipates the next sonnet, where the other two elements, air and fire, come into play. |

|

Receiving naught by elements so slow

But heavy tears, badges of either's woe. |

And I receive nothing from elements that are so slow, other than my own heavy tears which are the tokens of the sorrow they cause me by keeping me away from you.

|

Sonnet 44 is the first in two pairs of poems that together sit in a larger group of sonnets which see William Shakespeare spending time away from his young lover and expressing his anguish over this absence. It comes in an unequal coupling with Sonnet 45, whereby 44 can easily stand on its own, but 45 directly follows on from 44 and only makes sense when read in its context. And of course, we will look at them both together in the next episode. This instalment though focuses on 44.

When with Sonnet 43, Shakespeare picked up on the theme of separation he had previously reflected on in Sonnets 27 & 28, and loosely but unmistakably referenced elements contained therein of being kept awake by thoughts and visions of his absent lover or dreaming of him and seeing him in his sleep, Sonnet 44 takes an entirely different approach to the same basic situation: Shakespeare is away from his young man and wishes he could be with him. But Shakespeare, rather than imagining him or relating his own feelings about him, or even just praising his many exquisite qualities, as several other poems have done before, in Sonnet 44 sets up an elaborate argument about the constraints of being a physical entity in a world that is understood to be made of the four basic elements, earth, water, air, and fire.

Like Sonnet 43, Sonnet 44, and then even more so its extension, Sonnet 45, is curiously impassive. Yes, it speaks of 'heavy tears' and even features an expression of woe with its "But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought," but although they may be sincere, they don't strike us as particularly heartfelt or in that sense all that urgent. This is not a sonnet that seems to have a great internal force to move us, and it is not altogether surprising that such discussion as there is about this particular poem is pretty thin. The point it makes is simple enough and one that we can absolutely relate to: I wish I could teleport myself to be with you right now, rather than having to wait until I get back to see you. Obviously, Shakespeare had no conception of teleporting, and as we noted in the last episode and once or twice before, in his world the weight and sheer loneliness of being away from your lover for an extended period is not something any of us are ever likely to experience in the same way, because while we may not have teleportation, we do have myriad ways of staying connected in real time with vision and sound: when we imagine Shakespeare somewhere on tour, staying in guest houses or taverns, or even being hosted in a country house, we really don't know what it was like.

The sonnet, rather than providing any great new insights or revelations about Shakespeare, his state of mind, and the relationship, appears to be part of an emotionally calmer phase in Shakespeare's life, during which he is unable to directly and fully engage with his young man. We spoke, when looking at Sonnet 43, of this possibly being a period of boredom and limbo for him, and this sonnet, making an observation that – without ever wishing to cast aspersions on our poor Will – does come across as borderline banal, reinforces this impression. Little as we know about his precise circumstances, from what we glean, we cannot blame Shakespeare for feeling somewhat detached and underpowered, and perhaps taking a breather from the great upheaval that has gone before is just what is at this stage needed.

When with Sonnet 43, Shakespeare picked up on the theme of separation he had previously reflected on in Sonnets 27 & 28, and loosely but unmistakably referenced elements contained therein of being kept awake by thoughts and visions of his absent lover or dreaming of him and seeing him in his sleep, Sonnet 44 takes an entirely different approach to the same basic situation: Shakespeare is away from his young man and wishes he could be with him. But Shakespeare, rather than imagining him or relating his own feelings about him, or even just praising his many exquisite qualities, as several other poems have done before, in Sonnet 44 sets up an elaborate argument about the constraints of being a physical entity in a world that is understood to be made of the four basic elements, earth, water, air, and fire.

Like Sonnet 43, Sonnet 44, and then even more so its extension, Sonnet 45, is curiously impassive. Yes, it speaks of 'heavy tears' and even features an expression of woe with its "But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought," but although they may be sincere, they don't strike us as particularly heartfelt or in that sense all that urgent. This is not a sonnet that seems to have a great internal force to move us, and it is not altogether surprising that such discussion as there is about this particular poem is pretty thin. The point it makes is simple enough and one that we can absolutely relate to: I wish I could teleport myself to be with you right now, rather than having to wait until I get back to see you. Obviously, Shakespeare had no conception of teleporting, and as we noted in the last episode and once or twice before, in his world the weight and sheer loneliness of being away from your lover for an extended period is not something any of us are ever likely to experience in the same way, because while we may not have teleportation, we do have myriad ways of staying connected in real time with vision and sound: when we imagine Shakespeare somewhere on tour, staying in guest houses or taverns, or even being hosted in a country house, we really don't know what it was like.

The sonnet, rather than providing any great new insights or revelations about Shakespeare, his state of mind, and the relationship, appears to be part of an emotionally calmer phase in Shakespeare's life, during which he is unable to directly and fully engage with his young man. We spoke, when looking at Sonnet 43, of this possibly being a period of boredom and limbo for him, and this sonnet, making an observation that – without ever wishing to cast aspersions on our poor Will – does come across as borderline banal, reinforces this impression. Little as we know about his precise circumstances, from what we glean, we cannot blame Shakespeare for feeling somewhat detached and underpowered, and perhaps taking a breather from the great upheaval that has gone before is just what is at this stage needed.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!