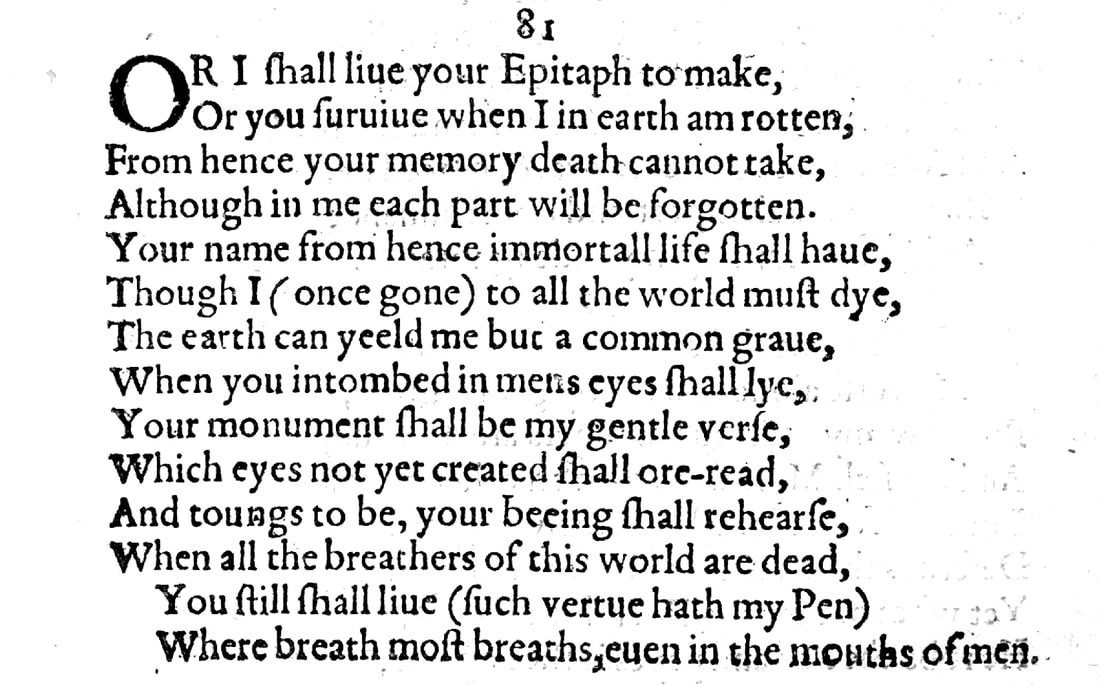

Sonnet 81: Or I Shall Live Your Epitaph to Make

|

Or I shall live your epitaph to make,

Or you survive when I in earth am rotten: From hence your memory death cannot take, Although in me each part will be forgotten. Your name from hence immortal life shall have, Though I, once gone, to all the world must die: The earth can yield me but a common grave, When you entombed in mens' eyes shall lie. Your monument shall be my gentle verse, Which eyes not yet created shall oreread, And tongues to be your being shall rehearse, When all the breathers of this world are dead. You still shall live, such virtue hath my pen, Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men. |

|

Or I shall live your epitaph to make,

Or you survive when I in earth am rotten, |

Either I shall live long enough to write your epitaph, because you die before I do, or you will survive me and live at a time when I am already rotting in my grave, but whichever happens to be the case, the following will unavoidably be true:...

The 'or...or' construction is one that is quite common in Shakespeare, and one we came across as recently as in the last line of Sonnet 75: Or gluttoning on all, or all away. There, as in most cases, its meaning is what we would put down as 'either ... or', but in this particular instance, we can also translate it as 'whether I shall live ... or whether you survive': the difference is minimal and the outcome to the argument the same. |

|

From hence your memory death cannot take,

Although in me each part will be forgotten. |

...death cannot take away the memory of you from here, even though everything about me will be forgotten.

The 'hence' possibly refers to both this place, as in this earth that we live on, and within that more specifically this culture, this society, we are part of, as well as to this time, as in 'henceforth', meaning from the moment that I write this poetry onwards, for reasons that shall become clear presently. Editors also point to the possibility of a tertiary meaning of 'from these lines'. In a more quotidian manner, we would say: 'death cannot take your memory from hence', but this type of reordering of words is really too common in poetry for it to register as truly remarkable, and so if we ignore this reversal, then the subsequent phrase "in me each part will be forgotten" presents a first small oddity about this poem, because it is genuinely unusual: a more commonplace way of expressing the thought would be to say something along the lines of: 'though every part of me will be forgotten', 'part of me' still meaning 'aspect of me' or 'thing about me', just as it does in Shakespeare's sentence. Whether he is here intentionally drawing attention to something that is contained in this poem that we don't recognise any more, or whether he is just playing around with words in an ever so slightly quirky way, we can't say, but this won't be the last time in this sonnet that he constellates components of the English language in a fashion that is capable of raising an eyebrow. even considering the time when this was written. |

|

Your name from hence immortal life shall have,

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die: |

Your name from hereon in – and here the temporal sense of 'hence' really takes over – shall live for ever, even though I, once I am gone, must needs to all the world be dead.

This, for us today, is doubly ironic, of course: Firstly, Shakespeare never once in these first 126 sonnets which, as we have come to recognise, are either all of them or mostly addressed to, written for, or composed about this young man, actually names him. And so while his personality, his character, the idea of him absolutely lives on with fulsome flavour, his name categorically doesn't, at least not through these sonnets, as far as we can tell. It is entirely possible, of course, that we are missing something, and that there is hidden somewhere within these sonnets a code that we are simply unable to decipher any more, or yet. Secondly, Shakespeare, though gone, has not died to all the world: he is very much alive and kicking, in our hearts, in our minds, on our stages, on our screens, in our books, in our podcasts, everywhere and every day, in our language. It is impossible to know to what extent Shakespeare is here being deliberately disingenuous or to what extent he truly believes that he will vanish from the mind of the world, while the subject of his poetry, through his poetry, will continue to live. But even for someone as slapdash with logic as Shakespeare has on occasion been known to be, this latter proposition is actually hard to conceive, because if the poetry survives, then surely, from about Homer onwards in Western culture, so does the poet... |

|

The earth can yield me but a common grave,

When you entombed in mens' eyes shall lie. |

All that the earth can offer me is an ordinary grave, when you will lie entombed in men's eyes.

The expression 'common grave' is liable to evoke in us a communal grave, as in a paupers' grave which is something Shakespeare may even be alluding to. But 'common' also simply means 'ordinary' and the image of an ordinary, simple grave is likely more relevant and more serviceable in contrast to an elaborate Elizabethan tomb. Rich people in Shakespeare's day held great store by their burial sites, and we have heard Shakespeare evoke such large, walk-in vault-like tombs – as featured prominently in Romeo & Juliet – in these sonnets before, not least in the exceptionally daring Sonnet 31: Thou art the grave where buried love doth live Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone Which is why the verb 'entombed' is so telling and so fitting here: the young man will not die, he will live on in an ever self-renewing tomb of readers to come, as the following lines are about to expound: |

|

Your monument shall be my gentle verse,

Which eyes not yet created shall oreread, |

Your monument that is made and maintained for your memory will be my gentle verse which will be read by eyes that have not yet been created, because the people they belong to have not yet been born.

It is fascinating that Shakespeare refers to his verse as 'gentle', to contrast it even further with the massive – possibly as may be implied, ostentatious, over-ornamented – memorial that would be typical of a nobleman's grave. Sonnet 55 made a very similar point: Not marble, nor the gilded monuments of princes Shall outlive this powerful rhyme, But you shall shine more bright in these contents Than unswept stone, besmeared with sluttish time. Like Sonnet 18 – "So long as men can breathe or eyes can see | So long lives this, and this gives life to thee" – and in fact all the other sonnets in the collection that have predicted an immortality for their subject, these lines too prove prophetic indeed, because our eyes, which were not yet created 430 years ago are 'over-reading' this 'gentle verse' of Shakespeare's, even as we speak. |

|

And tongues to be your being shall rehearse

When all the breathers of this world are dead. |

And similarly tongues which are at the time of writing this sonnet yet to be brought into the world because they belong to people of future generations, will speak of and reiterate your essence, recite what I have written about you, and they will do so at a time when all the human beings who live in this current world we live in – 'we' being Shakespeare and his young lover – are dead.

Which equally turns out to be true: that is exactly what we are doing, we are rehearsing – as in practising, reciting, repeating – these lines about the young man and thus his being, even though we don't know his name. |

|

You still shall live, such virtue hath my pen,

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men. |

You shall always and forever live, such is the virtuous or positive power that my pen is imbued with, where breath most breathes, in the very mouths of men.

And this surely is one of the oddest notions Shakespeare has ever planted in our brains: the young man as living in the breath of the people who speak these verses in times to come. It makes sense, certainly, it just feels very, very strange. And therein may, or may not, lie its own particular purpose or meaning... |

Sonnet 81, although it appears right in the middle of the Rival Poet group of sonnets, does not concern itself with any poet other than Shakespeare at all, and so it either marks a detour deliberately taken by Shakespeare from his preoccupation with his rival, or it presents an instance in which a sonnet has in fact slipped from its position and been mislaid here accidentally. On the surface, it doesn't do anything other sonnets have not done before: it promises and predicts an everlasting memorial to the young man in the form of itself – the poetry that Shakespeare composes for him – while downplaying the role of the poet in creating such a literary monument, and anticipating, wrongly as it turns out, that Shakespeare himself, unlike his young lover, the subject of the poem, will be entirely forgotten. The imagery and vocabulary it employs are so unusual though that they make us wonder whether there isn't more going on here than meets the eye.

Every time I read or recite this sonnet, I cannot get away from the suspicion – rather thrilling, if it were borne out to be justified – that with it, William Shakespeare is playing a little game with us. Vexingly, I don't know what the game is any more than any of the other editors and interpreters of Sonnet 81 that I have yet come across. And so before airing any of these thoughts at all, I am duty-bound to stress once again: we don't know anything, really, and it may be the case that this is just a poem that happens to sound to our ear slightly oddly composed, when to William Shakespeare and his young lover and the friends around them this sounds completely normal.

Way back in the episode covering Sonnet 27 I almost in passing alluded to something that in fact comes up every so often in these sonnets: Every so often what Shakespeare does reminds us of nothing so much as of a cryptic crossword setter, where he seems to arrange words in such a way that they make us want to look for something else; a way that suggests they are a pointer towards something which, if we were versed enough in his verses, we could find or decipher or even just guess. And while I reiterate we have no proof of this being the case here, it occurs to me that even if it isn't, then perhaps it should be. Because either that, or our Will is being lackadaisical. Which also, of course, is possible.

What makes me say all this? Imagine you are a really excellent poet who has written several plays that are being performed on the stage and seen by thousands of people every week, you are about to write, or have already by now written and published some narrative poems that prove to be remarkably commercially successful, you have this astonishingly involved and complex relationship with a man who is significantly younger, immeasurably richer, and vastly more powerful than you, and you are either right now going through a phase of upheaval where this young, rich, powerful lover of yours is beginning to favour someone else, or possibly, if this sonnet does find itself in the wrong place in the collection, this is soon to happen or has recently happened, and you now sit down to write, not for the first time, a poem that does absolutely nothing more interesting than tell this young man that he is going to live forever because of your poetry, while you yourself, who is even now writing that same poetry and therefore indelibly associated with it, will supposedly be dead to all the world.

Now, we can probably ignore, at least for the time-being, the logical flaw in a poet writing poetry that makes its subject live forever while he himself – we are talking mostly about men in this era, though not, it should be noted, exclusively – fades into oblivion. This idea is commonplace at the time.

We also perhaps don't even need to dwell all too long on the question that has on other occasions been particularly pertinent: why? Why write it? You've said as much before, what brings this on right now? Because recurring themes and repetitions in poetic pronouncements are absolutely nothing unusual then and now, and also if the possibility exists, as it does, that this poem finds itself out of place, then it may well be part of a group or align itself with another sonnet that deals with this particular theme.

The question that is especially worth looking at – to my mind – lies here: you are this highly skilled poet and you write this almost entirely uninteresting poem, but you do so in a really rather eye-catchingly interesting way. Again, it may not mean anything, it may just be that Shakespeare latches on to the word 'breather' to mean a person who breathes and who therefore is alive and then enjoys playing around for just a little while with the sound and sensation you get by saying :

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men.

A moment ago we ventured that this sonnet, like all the other sonnets that promise the young man eternal life through themselves, thus becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And that would be the case, except that strictly speaking, this sonnet does not do what it purports to do. It tells us exactly nothing about the young man. Unlike Sonnet 18, which compares its recipient – unsuccessfully, as it admits, but to wondrous effect – to a summer's day, unlike Sonnet 19, which pleads with Time to leave the young man's beauty untouched, Sonnet 81 gives us no information about its subject. At all.

It is not alone in this. William Shakespeare has a bit of a knack for saying that his verse will do something that it actually doesn't quite then fulfil: take Sonnet 53, for example, which for the second time following Sonnets 15 & 16 draws a comparison between the young man and a rose, and in this case speaks of distilling the young man's essence. If we take a narrow view, then Sonnet 53 does not accomplish its task: it sets up the analogy and talks about the power of poetry to preserve truth, but it does not in itself tell us anything new or particularly insightful, or let alone an especially revealing truth about the young lover.

Sonnet 60 does something similar: it talks at length about what time does to all things and especially to human beauty and then concludes:

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

Whereby the sum total of praise the young man gets from this sonnet is whatever we can perceive as being contained in the very last line. Sonnet 63 does almost the exact same thing, talking about the cruelty of time for twelve beautifully composed lines, to conclude:

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

Whereby the beauty of these lines lies entirely in the language: they are gorgeous, but say nothing at all about the young man.

And here, in Sonnet 81, the young man, and through him we, are being promised something of a eulogy which will keep him alive in our eyes and in the breath of our mouths and therefore in our hearts and minds, and yet nothing in this poem evokes him, at all.

Of course, we may be foolish to be taking a narrow view on this, as it is arguably foolish to take too narrow a view on anything, and if we zoom out and take a wider, more encompassing perspective, then we recognise easily enough – and as we have often noted throughout our exploration – a profile, a set of characteristics, a persona, a being. Which, if nothing else, gives us further good reason to do just that: take a step back now and then and look at these sonnets not as individual pieces, but as the many various and also varying components of a larger canvas that together form a coherent picture. Whether the odd poem is out of place or not then doesn't matter. Shakespeare is obviously speaking to the young man not in isolated instances and unconnected single sonnets and pairs, but across a thread that interweaves these sonnets into a unified work.

This doesn't solve the 'issue' we still have though: within this canvas, as part of the larger picture, here is a sonnet that looks and sounds decidedly odd. Why write it like that? And why be so specific when you're not delivering, it appears, on the promise? It is one thing saying "tongues to be your being shall rehearse," and we can respond to this in the affirmative and say: yes, Will, that's very much exactly what we are doing. It is quite another saying "Your name from hence immortal life shall have," when you never bother spelling out that name. There are myriad reasons why a poet like Shakespeare might not want to actually put the name of his lover into his poems, especially not if he is the kind of highly recognisable, high status, and – as some people today might call it - high value individual we have good reason to believe he is. And in any case, should we really take poetry literally? Ever? Is that not in itself just entirely missing the point?

Well yes, and no. It is and it would be, were it not for the fact that Shakespeare is making his sonnet sound so – odd. So unusually poetic, just not in the way we'd expect.

And this is where I feel inclined to leave it at. Simply because that's really all we have, we have a sense of something possibly being at work here of which we can't say what it is, or possibly not. And very much also because anything further that I might theorise that would point us towards a person, an actual name, would be so flimsy, so vague, so instinctive, rather than factual, it could easily be shot down. And that would distract us from what is really the focus of this group of sonnets, the Rival Poet.

But park this thought somewhere in the recess of your mind, because we will of course come back to it when we discuss the Fair Youth. There is something to this sonnet that to me says: speak these lines, say them out loud, and you will learn something about the recipient. And what makes me say this is mostly that if I were Shakespeare, that's how I would do it. Which does not mean that that's what he's done, I realise, of course... – And so, for the time-being, let us simply relish the fact that Shakespeare has given us, within the great treasure trove that is this volume of sonnets – a nugget that just may have a twinkle of a wink about it, saying to us look at me, listen to me, breathe me, and bring me to life.

Or not, as the case may be...

Every time I read or recite this sonnet, I cannot get away from the suspicion – rather thrilling, if it were borne out to be justified – that with it, William Shakespeare is playing a little game with us. Vexingly, I don't know what the game is any more than any of the other editors and interpreters of Sonnet 81 that I have yet come across. And so before airing any of these thoughts at all, I am duty-bound to stress once again: we don't know anything, really, and it may be the case that this is just a poem that happens to sound to our ear slightly oddly composed, when to William Shakespeare and his young lover and the friends around them this sounds completely normal.

Way back in the episode covering Sonnet 27 I almost in passing alluded to something that in fact comes up every so often in these sonnets: Every so often what Shakespeare does reminds us of nothing so much as of a cryptic crossword setter, where he seems to arrange words in such a way that they make us want to look for something else; a way that suggests they are a pointer towards something which, if we were versed enough in his verses, we could find or decipher or even just guess. And while I reiterate we have no proof of this being the case here, it occurs to me that even if it isn't, then perhaps it should be. Because either that, or our Will is being lackadaisical. Which also, of course, is possible.

What makes me say all this? Imagine you are a really excellent poet who has written several plays that are being performed on the stage and seen by thousands of people every week, you are about to write, or have already by now written and published some narrative poems that prove to be remarkably commercially successful, you have this astonishingly involved and complex relationship with a man who is significantly younger, immeasurably richer, and vastly more powerful than you, and you are either right now going through a phase of upheaval where this young, rich, powerful lover of yours is beginning to favour someone else, or possibly, if this sonnet does find itself in the wrong place in the collection, this is soon to happen or has recently happened, and you now sit down to write, not for the first time, a poem that does absolutely nothing more interesting than tell this young man that he is going to live forever because of your poetry, while you yourself, who is even now writing that same poetry and therefore indelibly associated with it, will supposedly be dead to all the world.

Now, we can probably ignore, at least for the time-being, the logical flaw in a poet writing poetry that makes its subject live forever while he himself – we are talking mostly about men in this era, though not, it should be noted, exclusively – fades into oblivion. This idea is commonplace at the time.

We also perhaps don't even need to dwell all too long on the question that has on other occasions been particularly pertinent: why? Why write it? You've said as much before, what brings this on right now? Because recurring themes and repetitions in poetic pronouncements are absolutely nothing unusual then and now, and also if the possibility exists, as it does, that this poem finds itself out of place, then it may well be part of a group or align itself with another sonnet that deals with this particular theme.

The question that is especially worth looking at – to my mind – lies here: you are this highly skilled poet and you write this almost entirely uninteresting poem, but you do so in a really rather eye-catchingly interesting way. Again, it may not mean anything, it may just be that Shakespeare latches on to the word 'breather' to mean a person who breathes and who therefore is alive and then enjoys playing around for just a little while with the sound and sensation you get by saying :

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men.

A moment ago we ventured that this sonnet, like all the other sonnets that promise the young man eternal life through themselves, thus becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And that would be the case, except that strictly speaking, this sonnet does not do what it purports to do. It tells us exactly nothing about the young man. Unlike Sonnet 18, which compares its recipient – unsuccessfully, as it admits, but to wondrous effect – to a summer's day, unlike Sonnet 19, which pleads with Time to leave the young man's beauty untouched, Sonnet 81 gives us no information about its subject. At all.

It is not alone in this. William Shakespeare has a bit of a knack for saying that his verse will do something that it actually doesn't quite then fulfil: take Sonnet 53, for example, which for the second time following Sonnets 15 & 16 draws a comparison between the young man and a rose, and in this case speaks of distilling the young man's essence. If we take a narrow view, then Sonnet 53 does not accomplish its task: it sets up the analogy and talks about the power of poetry to preserve truth, but it does not in itself tell us anything new or particularly insightful, or let alone an especially revealing truth about the young lover.

Sonnet 60 does something similar: it talks at length about what time does to all things and especially to human beauty and then concludes:

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

Whereby the sum total of praise the young man gets from this sonnet is whatever we can perceive as being contained in the very last line. Sonnet 63 does almost the exact same thing, talking about the cruelty of time for twelve beautifully composed lines, to conclude:

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

Whereby the beauty of these lines lies entirely in the language: they are gorgeous, but say nothing at all about the young man.

And here, in Sonnet 81, the young man, and through him we, are being promised something of a eulogy which will keep him alive in our eyes and in the breath of our mouths and therefore in our hearts and minds, and yet nothing in this poem evokes him, at all.

Of course, we may be foolish to be taking a narrow view on this, as it is arguably foolish to take too narrow a view on anything, and if we zoom out and take a wider, more encompassing perspective, then we recognise easily enough – and as we have often noted throughout our exploration – a profile, a set of characteristics, a persona, a being. Which, if nothing else, gives us further good reason to do just that: take a step back now and then and look at these sonnets not as individual pieces, but as the many various and also varying components of a larger canvas that together form a coherent picture. Whether the odd poem is out of place or not then doesn't matter. Shakespeare is obviously speaking to the young man not in isolated instances and unconnected single sonnets and pairs, but across a thread that interweaves these sonnets into a unified work.

This doesn't solve the 'issue' we still have though: within this canvas, as part of the larger picture, here is a sonnet that looks and sounds decidedly odd. Why write it like that? And why be so specific when you're not delivering, it appears, on the promise? It is one thing saying "tongues to be your being shall rehearse," and we can respond to this in the affirmative and say: yes, Will, that's very much exactly what we are doing. It is quite another saying "Your name from hence immortal life shall have," when you never bother spelling out that name. There are myriad reasons why a poet like Shakespeare might not want to actually put the name of his lover into his poems, especially not if he is the kind of highly recognisable, high status, and – as some people today might call it - high value individual we have good reason to believe he is. And in any case, should we really take poetry literally? Ever? Is that not in itself just entirely missing the point?

Well yes, and no. It is and it would be, were it not for the fact that Shakespeare is making his sonnet sound so – odd. So unusually poetic, just not in the way we'd expect.

And this is where I feel inclined to leave it at. Simply because that's really all we have, we have a sense of something possibly being at work here of which we can't say what it is, or possibly not. And very much also because anything further that I might theorise that would point us towards a person, an actual name, would be so flimsy, so vague, so instinctive, rather than factual, it could easily be shot down. And that would distract us from what is really the focus of this group of sonnets, the Rival Poet.

But park this thought somewhere in the recess of your mind, because we will of course come back to it when we discuss the Fair Youth. There is something to this sonnet that to me says: speak these lines, say them out loud, and you will learn something about the recipient. And what makes me say this is mostly that if I were Shakespeare, that's how I would do it. Which does not mean that that's what he's done, I realise, of course... – And so, for the time-being, let us simply relish the fact that Shakespeare has given us, within the great treasure trove that is this volume of sonnets – a nugget that just may have a twinkle of a wink about it, saying to us look at me, listen to me, breathe me, and bring me to life.

Or not, as the case may be...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!