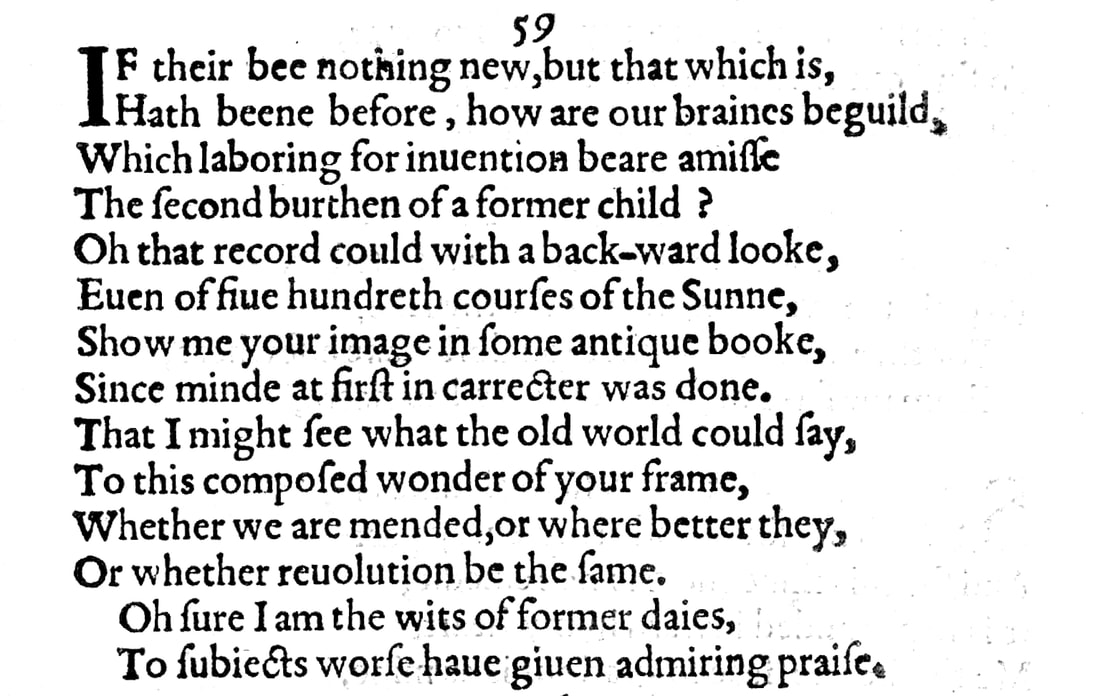

Sonnet 59: If There Be Nothing New, But That Which Is

|

If there be nothing new, but that which is

Hath been before, how are our brains beguiled, Which, labouring for invention, bear amiss The second burden of a former child. O that record could with a backward look, Even of five hundred courses of the sun, Show me your image in some antique book, Since mind at first in character was done, That I might see what the old world could say To this composed wonder of your frame: Whether we are mended or where better they, Or whether revolution be the same. O sure I am the wits of former days To subjects worse have given admiring praise. |

|

If there be nothing new, but that which is

Hath been before, how are our brains beguiled, |

If it is the case that there is nothing new under the sun, but in fact everything which is or exists today has already been or existed once or indeed several times before, then how are our brains deceived...

The proverb 'nothing new under the sun' goes back to ancient times and the idea of time moving in recurring cycles can be found at least as far back as Pythagoras. Most directly referenced here though is the Bible, Ecclesiastes Chapter 1, Verse 9: The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun. (King James Version) 'Beguile' for us today tends to have more positive connotations than it would have had in Elizabethan English, or certainly than it does here: we think of it more as 'charmed' or even 'enchanted', but the sense here is much closer to the Middle English meaning of 'thoroughly deceived'. |

|

Which, labouring for invention, bear amiss

The second burden of a former child. |

Our brains, striving for novelty or for the discovery of new arguments often mistake – bear amiss – the second iteration of something that has already once lived or been given birth to.

'Invention' can here be understood both in our more general sense of something that is newly brought about or 'invented', but seeing Shakespeare's knowledge of the ancient art of rhetoric and in the context of a piece of rhetorical or poetic writing such as a sonnet, it is very likely also a reference to inventio, which is one of the five canons of classical rhetoric and concerns itself with the search for arguments. The Latin inventio stems from invenire which literally means 'to come in' and can be variously translated as 'to come upon, find; find out; invent, discover, devise; ascertain; acquire, get, earn'. (Online Etymology Dictionary) This is not the first time that Shakespeare likens the writing of a poem – in both these cases – to the birth of a child. In Sonnet 32 he requested of his lover: O then vouchsafe me but this loving thought: Had my friend's muse grown with this growing age A dearer birth than this his love had brought To march in ranks of better equipage. And indeed Shakespeare is not alone in using this metaphor: it is fairly commonplace for the era. |

|

O that record could with a backward look,

Even of five hundred courses of he sun, Show me your image in some antique book Since mind at first in character was done, |

O I wish that the annals or written records of history could show me your image in an old book from the days when we first began to write down our thoughts or memories, even as far back as five or six hundred years...

We came across "the living record of your memory" as recently as Sonnet 55, where we noted that 'record' implies a written document. Here, for prosody, the word is stressed on the second syllable: recòrd. John Kerrigan in the New Penguin edition of the Sonnets points out that 'hundred' here likely refers to the 'great' or 'long' hundred of six score (6 X 20), which is 120, and so five hundred courses of the sun would amount to 600 years, rather than 500, to tally with the 600 annual cycles after which, according to ancient belief, an astrological constellation would recur. The 'image' that is here referred to at first glance seems to suggest a picture, but the following lines really make it clear that we are talking about a description, which of course aligns itself with the overall theme of poetry that is being discussed. 'Even', as so often, is pronounced with one syllable and 'antique' is stressed on the first syllable in order for the line to scan. |

|

That I might see what the old world could say

To this composed wonder of your frame: |

So that I might be able to see what the old world had to say about this wondrously beautiful, and harmoniously proportioned composition that is your form or body...

And with this we are firmly now in the territory of language and the composition of poetry to which this 'composed wonder' also alludes. Calling the young man's body a 'composition' is especially complimentary and glorious, as it elevates him effectively to a work of art that is consciously constructed in just the right proportions to make it perfect. |

|

Whether we are mended or where better they,

Or whether revolution be the same. |

...and to find out whether we have improved on their craft – are mended – or whether they were in fact better at describing your beauty, or whether this cycle of years that have gone by, this revolution, hasn't changed anything and we are exactly the same and therefore by implication as good as each other.

'Revolution' here does not mean the violent overthrow of a government or an uprising, it means the turn of a cycle. The Quarto Edition's where in this line is by most editors rendered as whe'er because it surely does mean 'whether' but the original spelling allows for a double meaning and invites us to read the question not only as whether we are better or they are, but also in what respects – where in the argument – we or they may be better. For this reason I have retained 'where' here. |

|

O sure I am the wits of former days

To subjects worse have given admiring praise. |

Oh, I am sure that the writers or poets or more generally chroniclers of former days have given admiring praise to subjects of less worth than you.

This is another instance – though perhaps milder in its potential power – of William Shakespeare introducing a twist to the closing couplet of a sonnet that on the surface appears to set out to be a simple eulogy. Because much as we couldn't determine for certain whether Sonnet 53 ended with a compliment to or a rebuke of the young man, so here the line can be read in two entirely contrasting ways. Either as: Oh, I am sure that even the most highly praised people of ancient times were nowhere near as worthy as you, or as: Oh I am sure that among the people praised in ancient times there were those who were even less worthy than you. Which it is we can't be sure, but the fact alone that both are possible is immensely telling... And 'given' here is pronounced with one syllable. |

Sonnet 59 takes us back into the realm of the proverb and the poetic commonplace and wonders how – if the old saying holds true that there is nothing new under the sun, but everything recurs in never ending cycles – a previous generation would have viewed and in poetry depicted the young man. Similar to Sonnet 53, it for the most part appears to present a pretty straightforward ode to the lover, but then undermines the praise it heaps upon him with a concluding couplet that can be read in two completely contradictory ways, which suggests that the conflict our poet feels for the object of his affections is far from resolved.

The philosophical observation that we may think we are discovering or indeed inventing things for the first time, but that actually everything that we think has been thought, everything that we say has been said, and everything that we do has been done before ushers in a reflective mood which sees William Shakespeare contemplate his existence, his age, and his own mortality within the much larger picture of a world in which time ultimately consumes everything and very little of what matters to us remains. The poem thus precipitates a group of sonnets – Sonnets 61-77 – which are sometimes postulated to have been written marginally before the group that now comes to a provisional 'close', Sonnets 1-60, which is something we need to be aware of, though we may also acknowledge, as scholars generally do, that these estimated times of composition are by their very nature imprecise and largely conjectural. And, as I foreshadowed a couple of times now, we will be talking about the issue of the timing of the sonnets and therefore of their sequentiality, such as it may or may not be, in a special episode very soon, after Sonnet 60.

Of particular interest to us in Sonnet 59 are two things: firstly this noticeable shift in tone. Curiously, one might argue it strikes a signally more mature, more sedate note than certainly the couple of sonnets that immediately precedes it, Sonnets 57 & 58, which we found difficult not to receive with a perceptible tinge of peeve, but it is also far more emotionally distanced than, say, Sonnets 52 and 53, less boastful than Sonnets 54 and 55, and less pleading than Sonnet 56. It seems to be taking a step back from all the turmoil of this relationship and of life generally and be saying to the young man, to Shakespeare himself, and now to us: beautiful people like you come into this world, and the world falls in love with you, and we poets who are part of the world and fall in love with you try our best to do you justice; often we fail, sometimes we think we may succeed, the challenge remains, it has ever been thus, but at least our words may overcome the ravages of time. This latter thought is not expressed in this poem itself, but it is almost taken as read by virtue of the fact that some 'antique book' is expected to exist, describing the beauty of former days, in which I wish I could see you describe. It is almost, in sentiment if not in literal expression, a summary of where we have got to so far.

But then, secondly, this closing couplet:

O sure I am the wits of former days

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

What is that all about? Let's recap the argument:

– First quatrain: if there is nothing new under the sun, then how wrong we are to think that we are discovering or inventing anything new, because everything we create is in fact nothing but a reincarnation, so to speak, of something that has existed at least once before. This is the premise.

– Second quatrain: accepting this premise and therefore that you or your like has lived before, I wish I could take some ancient tome from centuries ago...

– Third quatrain: ...to see how the poets of these ancient times handled this wonder that is your frame, that is so perfectly composed, and in doing so find out whether we today are better at painting a picture in words of you, or whether they were, or whether in fact we are much the same.

– Closing couplet: I am sure that these poets have given admiring praise to subjects that are worse than you. This doesn't follow, nor does it make any direct sense – not directly – and, as we have seen, it prompts us to think of a sudden inversion that says: oh I am sure these poets of the olden days have praised people who are even worse than you, in other words, I am not alone in praising imperfection.

The conclusion might make sense if we read the third quatrain differently and interpreted it as referring not to the depiction in writing of the subject at hand, but to the subject itself: the third and fourth line of the third quatrain could just about also be read as saying, whether we have better, more beautiful, more perfectly composed wonders to write about than they did, or whether theirs were in these senses better, or whether we have come 'full circle' and our generation is talking about a level of perfection that is just the same as theirs. With this reading, the closing couplet becomes refreshingly straightforward: oh, I am sure that whomever these ancient poets were praising was not as amazing as you are.

The problem with this reading is that we have to 'invent' it. The poem itself does not conduct that switch for us, it talks about "the composed wonder of your frame," and appears to plainly not compare a former similar version or quasi 'equivalent' of your frame to you today, but a former description of your frame, as we see it today, to our, specifically my, description today.

Now, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare, of whom we know and have established several times by now that he is not overly concerned with the strictures of logic and quite occasionally simply takes matters as read, wants us to make this jump for him and that for him it is clear that when he talks of "subjects worse" he obviously means subjects who simply had no chance of being as exquisitely composed as his subject, the young man.

Equally possible though is that Shakespeare, of whom we also know that he loves multiple layers of meaning and word play and puns and hidden clues, wants us to believe that that's what he wants us to do, but is actually using his conclusion to his sonnet to once again relay the deep ambiguity he feels about his lover. It is, after all, an ambiguity that has made itself felt on many occasions, and for as long as we have reason to believe that we are talking about the same young man, we know with some certainty that he is not unimpeachable.

How we want to read this last couple of lines is and remains most likely forever now up to us. It is, as I am doing this podcast, in decimal terms just about 430 revolutions of the sun since Shakespeare wrote this sonnet and in all likelihood many of the sonnets that surround it and that relate to us 'this composed wonder' of the young man's frame. And it is perhaps interesting that the sonnet this so instantly reminds us of, Sonnet 53, names Adonis and Helen, the two classical ideals of beauty, whom the 'wits of former days' have spent a great deal of ink on eulogising. It is tempting to think – and a lovely thought it is too – that Shakespeare views his young lover as even more perfect than them. And who knows, maybe if Shakespeare had named his young lover, he too would now be an icon of beauty that we refer to and recognise and whose descriptions in the past we can compare to contemporary ones.

But here the veil of mystery envelops our poet's lover and we may never know for certain whom we are hearing of or how exactly we should imagine them. And Shakespeare, throughout the series so far, has given us remarkably few clues: much as he has praised the young man, he has given us hardly any description. "A woman's face hast thou," he told him back in Sonnet 20, having spoken of "the beauty of your eyes," in Sonnet 17. In Sonnet 10 he told him that his presence is "gracious and kind," and in Sonnet 3 we learnt that he looks like his mother. We know he is young, we know he is rich, we know he is fickle, we know he is unfaithful, and we know they have been together and they have been apart and together again, but we really have to form our own image of him, certainly for as long as we keep our minds open as to who he is and don't resort to any portraits of any historical figures who may or may not be the young man. These poems yield us some clues, but none of them actually describes him, none of them does what this sonnet wishes an 'antique book' had done so Shakespeare could compare them. The counterpart of which Shakespeare seems to speak in his present does not exist any more than the former 'birth' he wishes he could consult.

And so perhaps here once again, as at least once before, we may have to accept that Shakespeare – be it consciously so or no – gives us two valid readings in one go which both are true: since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it may well be that as far as Shakespeare is concerned nobody has ever been as beautiful as this young man. But it is also the case that this perfect creature comes with his own pronounced character flaws and this fact, too, that beauty is not necessarily paired with an upright personality of unmatched integrity, has probably ever been thus.

Nothing new, indeed, then, under this sun...

The philosophical observation that we may think we are discovering or indeed inventing things for the first time, but that actually everything that we think has been thought, everything that we say has been said, and everything that we do has been done before ushers in a reflective mood which sees William Shakespeare contemplate his existence, his age, and his own mortality within the much larger picture of a world in which time ultimately consumes everything and very little of what matters to us remains. The poem thus precipitates a group of sonnets – Sonnets 61-77 – which are sometimes postulated to have been written marginally before the group that now comes to a provisional 'close', Sonnets 1-60, which is something we need to be aware of, though we may also acknowledge, as scholars generally do, that these estimated times of composition are by their very nature imprecise and largely conjectural. And, as I foreshadowed a couple of times now, we will be talking about the issue of the timing of the sonnets and therefore of their sequentiality, such as it may or may not be, in a special episode very soon, after Sonnet 60.

Of particular interest to us in Sonnet 59 are two things: firstly this noticeable shift in tone. Curiously, one might argue it strikes a signally more mature, more sedate note than certainly the couple of sonnets that immediately precedes it, Sonnets 57 & 58, which we found difficult not to receive with a perceptible tinge of peeve, but it is also far more emotionally distanced than, say, Sonnets 52 and 53, less boastful than Sonnets 54 and 55, and less pleading than Sonnet 56. It seems to be taking a step back from all the turmoil of this relationship and of life generally and be saying to the young man, to Shakespeare himself, and now to us: beautiful people like you come into this world, and the world falls in love with you, and we poets who are part of the world and fall in love with you try our best to do you justice; often we fail, sometimes we think we may succeed, the challenge remains, it has ever been thus, but at least our words may overcome the ravages of time. This latter thought is not expressed in this poem itself, but it is almost taken as read by virtue of the fact that some 'antique book' is expected to exist, describing the beauty of former days, in which I wish I could see you describe. It is almost, in sentiment if not in literal expression, a summary of where we have got to so far.

But then, secondly, this closing couplet:

O sure I am the wits of former days

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.

What is that all about? Let's recap the argument:

– First quatrain: if there is nothing new under the sun, then how wrong we are to think that we are discovering or inventing anything new, because everything we create is in fact nothing but a reincarnation, so to speak, of something that has existed at least once before. This is the premise.

– Second quatrain: accepting this premise and therefore that you or your like has lived before, I wish I could take some ancient tome from centuries ago...

– Third quatrain: ...to see how the poets of these ancient times handled this wonder that is your frame, that is so perfectly composed, and in doing so find out whether we today are better at painting a picture in words of you, or whether they were, or whether in fact we are much the same.

– Closing couplet: I am sure that these poets have given admiring praise to subjects that are worse than you. This doesn't follow, nor does it make any direct sense – not directly – and, as we have seen, it prompts us to think of a sudden inversion that says: oh I am sure these poets of the olden days have praised people who are even worse than you, in other words, I am not alone in praising imperfection.

The conclusion might make sense if we read the third quatrain differently and interpreted it as referring not to the depiction in writing of the subject at hand, but to the subject itself: the third and fourth line of the third quatrain could just about also be read as saying, whether we have better, more beautiful, more perfectly composed wonders to write about than they did, or whether theirs were in these senses better, or whether we have come 'full circle' and our generation is talking about a level of perfection that is just the same as theirs. With this reading, the closing couplet becomes refreshingly straightforward: oh, I am sure that whomever these ancient poets were praising was not as amazing as you are.

The problem with this reading is that we have to 'invent' it. The poem itself does not conduct that switch for us, it talks about "the composed wonder of your frame," and appears to plainly not compare a former similar version or quasi 'equivalent' of your frame to you today, but a former description of your frame, as we see it today, to our, specifically my, description today.

Now, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare, of whom we know and have established several times by now that he is not overly concerned with the strictures of logic and quite occasionally simply takes matters as read, wants us to make this jump for him and that for him it is clear that when he talks of "subjects worse" he obviously means subjects who simply had no chance of being as exquisitely composed as his subject, the young man.

Equally possible though is that Shakespeare, of whom we also know that he loves multiple layers of meaning and word play and puns and hidden clues, wants us to believe that that's what he wants us to do, but is actually using his conclusion to his sonnet to once again relay the deep ambiguity he feels about his lover. It is, after all, an ambiguity that has made itself felt on many occasions, and for as long as we have reason to believe that we are talking about the same young man, we know with some certainty that he is not unimpeachable.

How we want to read this last couple of lines is and remains most likely forever now up to us. It is, as I am doing this podcast, in decimal terms just about 430 revolutions of the sun since Shakespeare wrote this sonnet and in all likelihood many of the sonnets that surround it and that relate to us 'this composed wonder' of the young man's frame. And it is perhaps interesting that the sonnet this so instantly reminds us of, Sonnet 53, names Adonis and Helen, the two classical ideals of beauty, whom the 'wits of former days' have spent a great deal of ink on eulogising. It is tempting to think – and a lovely thought it is too – that Shakespeare views his young lover as even more perfect than them. And who knows, maybe if Shakespeare had named his young lover, he too would now be an icon of beauty that we refer to and recognise and whose descriptions in the past we can compare to contemporary ones.

But here the veil of mystery envelops our poet's lover and we may never know for certain whom we are hearing of or how exactly we should imagine them. And Shakespeare, throughout the series so far, has given us remarkably few clues: much as he has praised the young man, he has given us hardly any description. "A woman's face hast thou," he told him back in Sonnet 20, having spoken of "the beauty of your eyes," in Sonnet 17. In Sonnet 10 he told him that his presence is "gracious and kind," and in Sonnet 3 we learnt that he looks like his mother. We know he is young, we know he is rich, we know he is fickle, we know he is unfaithful, and we know they have been together and they have been apart and together again, but we really have to form our own image of him, certainly for as long as we keep our minds open as to who he is and don't resort to any portraits of any historical figures who may or may not be the young man. These poems yield us some clues, but none of them actually describes him, none of them does what this sonnet wishes an 'antique book' had done so Shakespeare could compare them. The counterpart of which Shakespeare seems to speak in his present does not exist any more than the former 'birth' he wishes he could consult.

And so perhaps here once again, as at least once before, we may have to accept that Shakespeare – be it consciously so or no – gives us two valid readings in one go which both are true: since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it may well be that as far as Shakespeare is concerned nobody has ever been as beautiful as this young man. But it is also the case that this perfect creature comes with his own pronounced character flaws and this fact, too, that beauty is not necessarily paired with an upright personality of unmatched integrity, has probably ever been thus.

Nothing new, indeed, then, under this sun...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!