Sonnet 47: Betwixt Mine Eye and Heart a League Is Took

|

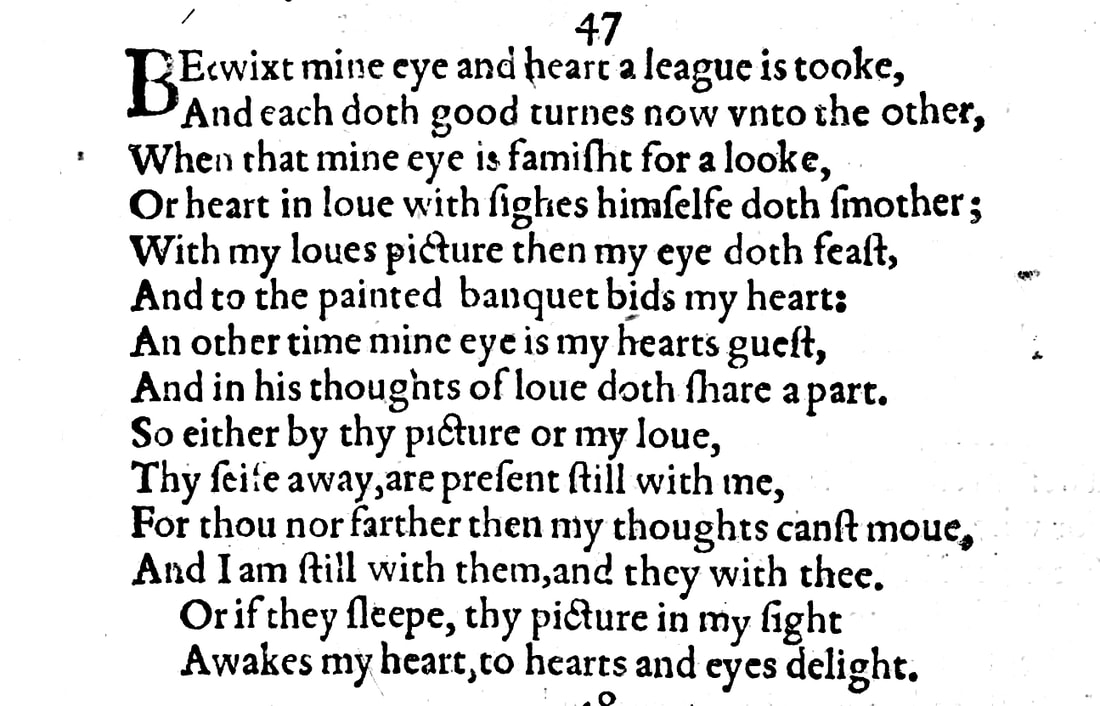

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

And each doth good turns now unto the other: When that mine eye is famished for a look, Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother, With my love's picture then my eye doth feast And to the painted banquet bids my heart; Another time mine eye is my heart's guest And in his thoughts of love doth share a part. So either by thy picture or my love, Thyself away are present still with me, For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move And I am still with them, and they with thee; Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight Awakes my heart, to heart's and eye's delight. |

|

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

|

The sonnet continues from Sonnet 46, which ended with a Solomonic judgment by the jury of thoughts, allocating the lover's outward appearance to the eye and his inward love to the heart.

My eye and my heart have entered an alliance... 'League' here is an alliance or also a peace treaty that allows two warring parties to work together. |

|

And each doth good turns now unto the other:

|

...and now that their dispute is resolved, they both do each other favours and help each other out.

|

|

When that mine eye is famished for a look,

|

And here are examples of this:

When my eye is longing to see you... 'Famished' of course means 'starved' or 'extremely hungry', which leads to the metaphor of the 'feast' and 'painted banquet' in just a moment, and it also underlines the impression we are getting – further confirmed later in the sonnet – that Shakespeare is away from his lover and that, as we were more or less able to establish, this separation is an extended one. |

|

Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother,

|

...or when my heart smothers itself with sighs because it is so in love with you...

Both heart and eye are here again mildly personified, in that they are referred to by a personal pronoun, but not capitalised in either the Quarto Edition or in the majority of current ones. |

|

With my love's picture then my eye doth feast,

And to the painted banquet bids my heart; |

...then, on such occasions, my eye feasts on a picture of you and invites my heart to this painted banquet, so my heart can share the delight that derives from it.

It is interesting to note that Shakespeare briefly switches from addressing the young man directly, as he did throughout Sonnet 46 and as he will be doing again throughout the rest of this sonnet, to talking about him in the third person. There is no obvious explanation for this, other perhaps than that 'feasting on a love's picture' is once more something of a poetic commonplace, and it also gives Shakespeare an opportunity to make it clear that you, the young man, are indeed my love and the person my heart is in love with, and not some random substitute. 'My eye', meanwhile is unusual, as Shakespeare fairly consistently uses the form 'mine' after a vowel sound, and whether this is a mistake here, or, as has been suggested, a way of retaining symmetry with 'my love's picture' that precedes it in the same line and 'my heart' that follows it in the next line cannot be said with any certainty, not least because in a moment Shakespeare will use 'mine eye' and 'my heart' right next to each other. |

|

Another time mine eye is my heart's guest,

And in his thoughts of love doth share a part. |

On another occasion, it will be my eye who will by my heart's guest – implied is by a similar welcome or invitation – to share in his, my heart's, thoughts of love for you, which are similarly edifying.

John Kerrigan points out that Shakespeare frequently associates the heart with thought, rather than – as we would today – mostly with emotion, science since having located thought mostly in the brain. And indeed the previous Sonnet 46 had thoughts as 'tenants to the heart', and in a little while, in Sonnet 69, he will be speaking of 'the thought of hearts'. |

|

So either by thy picture or my love,

Thyself away are present still with me, |

And so either by looking at your picture or by my heart's thoughts of love for you I can keep you close to me even when you are away.

Another minor anomaly is the 'are' in "Thyself away are present still with me," where we would expect 'art' to go with 'thyself', but this is not entirely uncommon in Shakespeare, when the verb is followed by a consonant. |

|

For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move,

And I am still with them and they with thee, |

Because you cannot move further away from me than my thoughts, but I am always with my thoughts and my thoughts are always with you.

|

|

Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart, to heart's and eye's delight. |

Or if they, my thoughts, are asleep and for some reason not thinking of you, then simply looking at your picture will awaken the heart again, to the delight of both my heart and eye.

Which confirms that, as the first line suggested, heart and eye have not merely signed a truce or stopped fighting over you, they now actively share the pleasure that comes from looking at your picture and thinking of you. |

Sonnet 47 again follows on directly from Sonnet 46, developing the argument further and arriving at a conclusion which is also maybe not altogether surprising, but which validates the premise set out with Sonnet 46 much more than that on its own led us to expect, thus tying Sonnet 46 tightly into this couple as a unit:

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war

How to divide the conquest of thy sight:

Mine eye my heart thy picture's sight would bar,

My heart mine eye the freedom of that right.

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

A closet never pierced with crystal eyes,

But the defendant doth that plea deny

And says in him thy fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye's moiety and the dear heart's part

As thus: mine eye's due is thy outward part

And my heart's right thy inward love of heart.

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

And each doth good turns now unto the other:

When that mine eye is famished for a look,

Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother,

With my love's picture then my eye doth feast

And to the painted banquet bids my heart;

Another time mine eye is my heart's guest

And in his thoughts of love doth share a part.

So either by thy picture or my love,

Thyself away are present still with me,

For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move

And I am still with them, and they with thee;

Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart, to heart's and eye's delight.

The war between eye and heart is amicably resolved: following the wise judgement of thoughts – which, as we noted, are by Shakespeare not associated with the head so much as with the heart and who therefore could be said to favour the heart – heart and eye now play together, supporting each other and helping each other out when in crisis. The eye, when it feels hungry for a look at the beautiful young man, feasts on his picture, and it does not do so alone, it invites the lonely lovesick heart to relish the nourishment it receives as well. Similarly, heart allows eye to share its tender thoughts of love when it soothes itself with wistful memories and hopeful longing.

The balance in me, the poet, is restored, and I stand a good chance, in this way, of sustaining myself through our period of separation, because, and this is the real insight the sonnet provides and at the same time 'message', if any, that it sends to the young man: thanks to this interplay between my eye and heart, you are always with me, no matter where you are, because when my thoughts are with you then I am with you, since I am by necessity always with my thoughts, and should my thoughts for any reason be 'asleep', for which read not actively with you, then all it takes for me is to look at your picture and both my heart and my eye are once again delighted and my thoughts naturally return to you straight away.

It is not groundbreaking poetry, nor does it really entirely stack up to the rational mind: there are, once again, easily detectable flaws in the argumentation, but it would feel churlish, even petty, to now point them out yet again. Shakespeare here as on previous occasions is not trying to convince an actual jury or prove a point of scientific interest, he is essentially improvising on well rehearsed themes in poetry, with the previous couple on the four elements, with this couple on the dispute twixt eye and heart.

It makes these two pairs – 44 & 45 and 46 & 47 – a curious square in the canon which most likely doesn't ignite any passion because it isn't intended to. If William Shakespeare were a twentieth century musician and the sonnets his songs, then these four would probably feature on the fourth album approximately, when the artist has produced a fair amount of work with a few notable hits and now finds himself with a bit of time on his hands to experiment with some ideas and concepts that make for listenable material but are clearly not going to chart as singles.

Which may provide us with an opportune moment to remind ourselves – if just briefly – that we simply don't know how the collection we have today came about and whether any of these sonnets were ever intended to be published. We don't know whether the young man they refer to ever got to read them, and if so what he made of them. This is not true of the entire series: there are some sonnets which strongly suggest that Shakespeare uses them as a form of communication and even some that appear to give us clues as to what the young man's response may have been. One such example that springs to mind is Sonnet 26, of which we said it sounds just like the kind of note you write when you've been rebuked. But this group gives us no such indication. Still, it has found itself into the canon and this in a position where it makes sense, and so we are probably allowed to simply accept that Shakespeare wrote these sonnets either for his own diversion or therapeutic purposes, or as a continuing stream of messages to his lover during this time when they are clearly apart.

The steady, nearly soothing calm these two times two sonnets seem to signal is now nearing its end though. What comes next is a riveting waveform of doubt, anguish, sorrow, followed by overwhelming joy and bliss, yielding into fully restored confidence as poet, just before it all goes haywire again. And so if you listened to the episode on Sonnet 43 and were wondering when exactly you should be thinking of putting on your safety belt: now is good time, because this was nothing if not the calm before a fabulously bracing new storm that will prove both truly invigorating, and really rather devastating too...

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war

How to divide the conquest of thy sight:

Mine eye my heart thy picture's sight would bar,

My heart mine eye the freedom of that right.

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

A closet never pierced with crystal eyes,

But the defendant doth that plea deny

And says in him thy fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye's moiety and the dear heart's part

As thus: mine eye's due is thy outward part

And my heart's right thy inward love of heart.

Betwixt mine eye and heart a league is took,

And each doth good turns now unto the other:

When that mine eye is famished for a look,

Or heart in love with sighs himself doth smother,

With my love's picture then my eye doth feast

And to the painted banquet bids my heart;

Another time mine eye is my heart's guest

And in his thoughts of love doth share a part.

So either by thy picture or my love,

Thyself away are present still with me,

For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move

And I am still with them, and they with thee;

Or if they sleep, thy picture in my sight

Awakes my heart, to heart's and eye's delight.

The war between eye and heart is amicably resolved: following the wise judgement of thoughts – which, as we noted, are by Shakespeare not associated with the head so much as with the heart and who therefore could be said to favour the heart – heart and eye now play together, supporting each other and helping each other out when in crisis. The eye, when it feels hungry for a look at the beautiful young man, feasts on his picture, and it does not do so alone, it invites the lonely lovesick heart to relish the nourishment it receives as well. Similarly, heart allows eye to share its tender thoughts of love when it soothes itself with wistful memories and hopeful longing.

The balance in me, the poet, is restored, and I stand a good chance, in this way, of sustaining myself through our period of separation, because, and this is the real insight the sonnet provides and at the same time 'message', if any, that it sends to the young man: thanks to this interplay between my eye and heart, you are always with me, no matter where you are, because when my thoughts are with you then I am with you, since I am by necessity always with my thoughts, and should my thoughts for any reason be 'asleep', for which read not actively with you, then all it takes for me is to look at your picture and both my heart and my eye are once again delighted and my thoughts naturally return to you straight away.

It is not groundbreaking poetry, nor does it really entirely stack up to the rational mind: there are, once again, easily detectable flaws in the argumentation, but it would feel churlish, even petty, to now point them out yet again. Shakespeare here as on previous occasions is not trying to convince an actual jury or prove a point of scientific interest, he is essentially improvising on well rehearsed themes in poetry, with the previous couple on the four elements, with this couple on the dispute twixt eye and heart.

It makes these two pairs – 44 & 45 and 46 & 47 – a curious square in the canon which most likely doesn't ignite any passion because it isn't intended to. If William Shakespeare were a twentieth century musician and the sonnets his songs, then these four would probably feature on the fourth album approximately, when the artist has produced a fair amount of work with a few notable hits and now finds himself with a bit of time on his hands to experiment with some ideas and concepts that make for listenable material but are clearly not going to chart as singles.

Which may provide us with an opportune moment to remind ourselves – if just briefly – that we simply don't know how the collection we have today came about and whether any of these sonnets were ever intended to be published. We don't know whether the young man they refer to ever got to read them, and if so what he made of them. This is not true of the entire series: there are some sonnets which strongly suggest that Shakespeare uses them as a form of communication and even some that appear to give us clues as to what the young man's response may have been. One such example that springs to mind is Sonnet 26, of which we said it sounds just like the kind of note you write when you've been rebuked. But this group gives us no such indication. Still, it has found itself into the canon and this in a position where it makes sense, and so we are probably allowed to simply accept that Shakespeare wrote these sonnets either for his own diversion or therapeutic purposes, or as a continuing stream of messages to his lover during this time when they are clearly apart.

The steady, nearly soothing calm these two times two sonnets seem to signal is now nearing its end though. What comes next is a riveting waveform of doubt, anguish, sorrow, followed by overwhelming joy and bliss, yielding into fully restored confidence as poet, just before it all goes haywire again. And so if you listened to the episode on Sonnet 43 and were wondering when exactly you should be thinking of putting on your safety belt: now is good time, because this was nothing if not the calm before a fabulously bracing new storm that will prove both truly invigorating, and really rather devastating too...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!