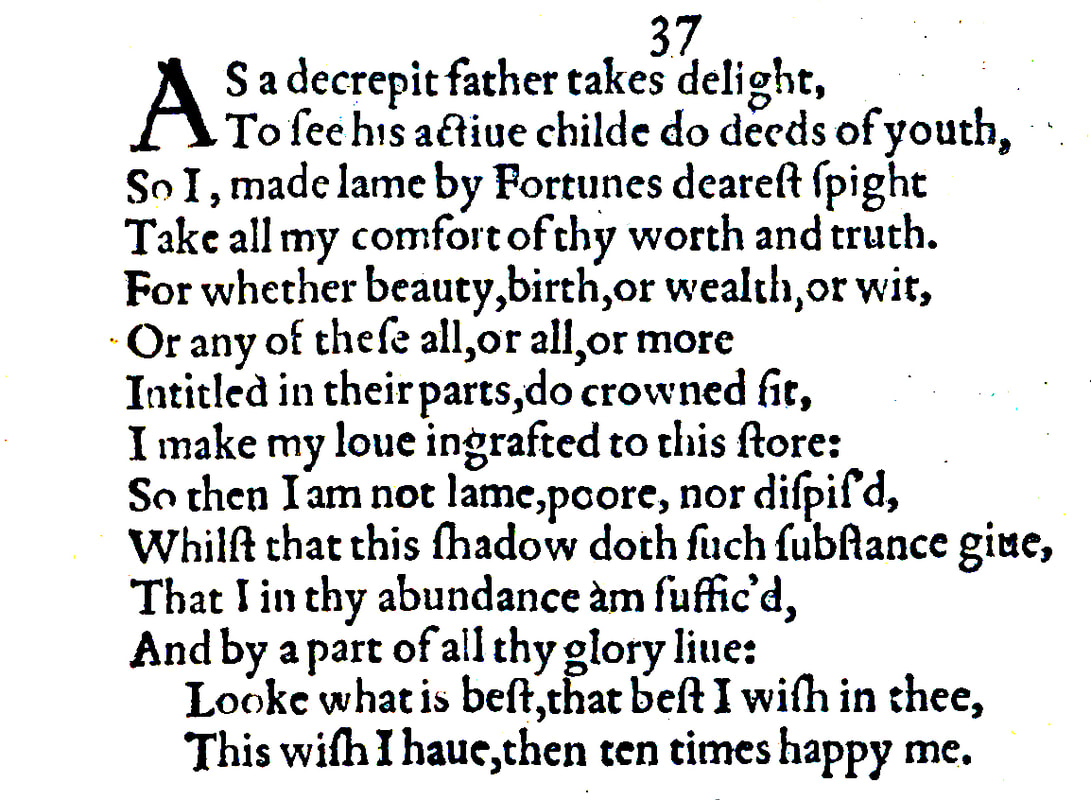

Sonnet 37: As a Decrepit Father Takes Delight

|

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth, So I, made lame by Fortune's dearest spite, Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth. For whether beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit, Or any of these all, or all, or more Entitled in thy parts do crowned sit, I make my love engrafted to this store; So then I am not lame, poor, nor despised, Whilst that this shadow doth such substance give That I in thy abundance am sufficed And by a part of all thy glory live. Look what is best, that best I wish in thee, This wish I have, then ten times happy me. |

|

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth, |

Like a father who is now advanced in his years and in his own strength and activities limited and who therefore enjoys watching his child do the things children do...

The adjective 'decrepit' sounds more harsh to us than it most likely is intended: Shakespeare points out this imagined father's age and the fact that he is now past his prime and also past his peak strength. The fact alone though that he is observing his "active child to deeds of youth" suggests he isn't as old as this makes him out to be. It is a reminder that in Shakespeare's day, people age fast – much faster than today – and that at thirty – which could easily be the age of a father of young children, you are considered old. For us, a 30-something dad is a young man with an average life expectancy of another fifty years ahead of him. This is not the case in Shakespeare's day, as we have seen before, where the average life expectancy of a male lies around the thirty mark, and this perception, and indeed experience of age, is entirely crucial to our understanding of Shakespeare's state of heart and mind during the entire Fair Youth series. |

|

So I, made lame by Fortune's dearest spite,

Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth. |

...so do I, who I am paralysed by my extremely bad luck, take all my comfort from your great qualities and your truthfulness, which suggests both fidelity to me, but also to yourself: your integrity.

This – as the whole sonnet – may come as something of a surprise so hard on the heels of the turmoil of Sonnets 33 to 36, but we will address the issue of sequence in a little more detail in a moment. The 'dearest spite', meanwhile, may lend itself to confusion to our minds. It simply means the most intense, most complete, most heartfelt maliciousness with which Fortune, here personified, treats me. This spite is not 'dear' to me, it is simply the highest level of spite there is. |

|

For whether beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit,

Or any of these all, or all, or more, Entitled in thy parts do crowned sit, |

And here these qualities are enumerated: because whether it be your beauty, your birth, meaning your birthright and therefore social status: your parentage, your wealth – which, we have noted, if this is the person we think it might be or anyone remotely similar is almost beyond measure substantial – or your wit, for which read your bright and keen intellect and impeccable social skills, or any of these, or all of these, or more than these, take their seat among your innumerable gifts, as indeed they are entitled to do, and in doing so they are crowned there, meaning they are given the privileged status that they deserve, and that, by inference they then bestow on you who is equally deserving.

The Quarto Edition has 'entitled in their parts do crowned sit' which – as so often with 'their' and 'thy' – most editors take to be a typesetting error. |

|

I make my love engrafted to this store;

|

I graft my love onto this rich, powerful, and successful store or stock of qualities, so that I may draw strength and nourishment from it and grow with it.

This provides an interesting contrast – which may or may not be consciously intended – to Sonnet 15 where Shakespeare boldly declared: And all in war with Time for love of you, As he takes from you, I engraft you new. And although it feels less visceral and far less sexual here, the notion of a symbiosis – a growing together and a mutual dependency – certainly reverberates. |

|

So then I am not lame, poor, nor despised

|

This way I am then no longer lame, poor, or despised...

The stated condition earlier on had been that I am "made lame by Fortune's dearest spite," and this here is qualified further: the spite with which Fortune treats me apparently – and congruently – also makes me poor and despised. To some extent it confirms our impression that reiterated here is the sentiment also contained in Sonnet 25 Let Those Who Are in Favour With Their Stars and Sonnet 29 When in Disgrace With Fortune and Men's Eyes, which both emphasise the poet's pitiful status. |

|

Whilst that this shadow doth such substance give

That I in thy abundance am sufficed And by a part of all thy glory live. |

While the mere shadow of your qualities infuses me with such substance that I can live off the great and abundant riches you have.

The use of the word 'shadow' here is intriguing. We have encountered it to mean 'image' or also 'vision' before, such as in Sonnet 27, where "my soul's imaginary sight / Presents thy shadow to my sightless view." Editors tend to point out that the relationship between a substance and its shadow is often used by Shakespeare and other poets, and here Shakespeare rather ingeniously inverts this: ordinarily it is a body of substance that produces a shadow, but here the metaphorical body of all the young man's qualities is so powerful that its mere shadow is capable of lending substance to his poor poet lover. |

|

Look what is best, that best I wish in thee,

This wish I have, then ten times happy me. |

See or think of the best anyone could wish for: that is what I wish for you; and since – or also so long as – you have everything I could wish for you, I am a ten times happier man.

|

In the first of three sonnets that appear to disrupt the sequence that concerns itself with the young man's evident infidelity, Sonnet 37 revisits the themes previously encountered of the poet's keenly felt lack of luck, absence of esteem, and sorely missing success, and contrasts this with the young man's abundant riches, both material and metaphorical, describing them as a source of sustenance and survival even while Fortune bestows her gifts elsewhere.

When Sonnet 36 already posed the question whether it finds itself entirely in the right place, but could still credibly – albeit tentatively – be connected to the events that have been unfolding since Sonnet 33, Sonnet 37 makes its appearance somewhat out of the blue, although it does relate, as we have seen and noted, to the sonnets earlier in the series which made it clear beyond reasonable doubt that Shakespeare is going through a period in his life when he does not feel favoured by the stars, nor appreciated by the people whose approval he craves, most obviously Sonnets 25 and 29. This has prompted editors – including myself – to wonder whether at this juncture the poems have got out of sequence and whether Sonnets 37, 38, and 39 have been placed here simply by mistake. Where exactly they belong, though, is unclear and it would seem that even if they have slipped somewhat in their position, they still belong into this larger group: interestingly, Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells in their attempt to regroup the sonnets according to their most likely years of composition keep the entire sequence from Sonnet 1 through Sonnet 60 intact.

We will discuss the 'problem of the sequence', which has engaged readers', listeners' and scholars' minds more or less ever since the sonnets first were published in 1609 in a dedicated episode in the not too distant future, but it is absolutely necessary and therefore appropriate that we flag it up here and are aware that our 'narrative flow' – which in itself is subject to much debate among scholars – here is stemmed and diverted, if only for a very short interlude.

Sonnet 37 does not tell us anything particularly new, but – quite apart from its own poetic purpose, which appears to be to relate Shakespeare's love to the young man and to find yet another angle to essentially praise him – it does confirm for us several significant aspects to the relationship and more than to the relationship to the constellation of the two men.

First, Shakespeare's age and his perception of age. This is a recurring theme which we have talked about on several occasions, including just above in the 'translation', and it will come up many times more: the sonnet is entirely consistent with everything we have learnt so far about the approximate timeframe and therefore Shakespeare's approximate age at the time he writes these sonnets. Edmondson and Wells date this group specifically to 1595 to 1597, which would mean that Shakespeare would be in his very early thirties. This – although unprovable – tallies well with our impressions and the resulting assumptions so far that the relationship with the young man starts when Shakespeare has either just turned or is about to turn 30, which for many a young man today is a big milestone, but for a man in Elizabethan England is roughly comparable to someone in our era turning 50 or possibly even 60: it is a big deal.

I do emphasise this point a bit, arguably to the point of labouring it, but it is entirely fundamental: a great many of these sonnets individually, but most importantly the entire relationship between Shakespeare and his young lover only make sense if we think of William Shakespeare as someone who sees himself past his prime. The great irony is of course that as a playwright he is at this stage only just about to enter the period of his greatest achievements, but he clearly does not know, not even really sense that. What he senses is that he is old and that this man whom he feels a great love and consuming passion for, by contrast, is at his peak. And yet, the difference in age between them cannot be more than about ten to twelve years. For us today, this is hard to comprehend: not only do we not see thirty as anything resembling old, we also don't see all that much of a difference between a 21 year old and a 31 year old. For William Shakespeare there is a world between them.

Not as big a world though, as there is in terms of status. This is the second notion we have not so much revealed here as confirmed: the young man, in every way conceivable, inhabits a different social sphere to that of William Shakespeare. His beauty and his wit could come from anywhere, but his birth – for which read birthright and class – and his wealth are clearly put in his cradle by his parentage. Which is exactly what we've been thinking all along: every indication we have had so far has pointed us to an extraordinarily well-situated English nobleman. You will find people arguing that some of these sonnets are so candid in tone and take such a dim view of some of the things that the young man does that they couldn't possibly be addressed to someone as exalted as the Third Earl of Southampton, or the Third Earl of Pembroke, for that matter, but time and again, and here in Sonnet 37 too, Shakespeare leaves little doubt that he is talking directly to someone who is essentially out of his league.

And the third element that we see again not newly uncovered so much as bedding down into our arrangement of facts and, by the absence of knowable, provable facts, plausible fabrications or conjectures, is that Shakespeare is in fact in love. It is worth every so often reminding ourselves just how extraordinary these sonnets really are. Because yes, it is true: romantic relationships between men are not as unusual in Elizabethan England as all that, and yes, the sonnet is by origin a format devised for the communication of love, and yes in Shakespeare's day the word 'love' may entail a wide spectrum of affection, devotion, loyalty, friendship, kinship, or a meeting of hearts and minds, but here a man is pouring into verse his love for another man at a time when there is simply no framework for celebrating such a love between men and when – though this, to be sure, happens extremely rarely even in Elizabethan England – men can be, and are, tortured to death for the physical expression of this kind of love. And so Sonnet 37, even if at first glance it may not seem particularly noteworthy, turns out to be entirely worth taking note of.

The thematic detour Shakespeare has either embarked, or the first editor of his sonnets has sent us off, on continues with two poems that shed yet more clarifying light on our poet and his young lover, before we then return to the young lover's deeds and misdemeanours that have so upset our poet...

When Sonnet 36 already posed the question whether it finds itself entirely in the right place, but could still credibly – albeit tentatively – be connected to the events that have been unfolding since Sonnet 33, Sonnet 37 makes its appearance somewhat out of the blue, although it does relate, as we have seen and noted, to the sonnets earlier in the series which made it clear beyond reasonable doubt that Shakespeare is going through a period in his life when he does not feel favoured by the stars, nor appreciated by the people whose approval he craves, most obviously Sonnets 25 and 29. This has prompted editors – including myself – to wonder whether at this juncture the poems have got out of sequence and whether Sonnets 37, 38, and 39 have been placed here simply by mistake. Where exactly they belong, though, is unclear and it would seem that even if they have slipped somewhat in their position, they still belong into this larger group: interestingly, Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells in their attempt to regroup the sonnets according to their most likely years of composition keep the entire sequence from Sonnet 1 through Sonnet 60 intact.

We will discuss the 'problem of the sequence', which has engaged readers', listeners' and scholars' minds more or less ever since the sonnets first were published in 1609 in a dedicated episode in the not too distant future, but it is absolutely necessary and therefore appropriate that we flag it up here and are aware that our 'narrative flow' – which in itself is subject to much debate among scholars – here is stemmed and diverted, if only for a very short interlude.

Sonnet 37 does not tell us anything particularly new, but – quite apart from its own poetic purpose, which appears to be to relate Shakespeare's love to the young man and to find yet another angle to essentially praise him – it does confirm for us several significant aspects to the relationship and more than to the relationship to the constellation of the two men.

First, Shakespeare's age and his perception of age. This is a recurring theme which we have talked about on several occasions, including just above in the 'translation', and it will come up many times more: the sonnet is entirely consistent with everything we have learnt so far about the approximate timeframe and therefore Shakespeare's approximate age at the time he writes these sonnets. Edmondson and Wells date this group specifically to 1595 to 1597, which would mean that Shakespeare would be in his very early thirties. This – although unprovable – tallies well with our impressions and the resulting assumptions so far that the relationship with the young man starts when Shakespeare has either just turned or is about to turn 30, which for many a young man today is a big milestone, but for a man in Elizabethan England is roughly comparable to someone in our era turning 50 or possibly even 60: it is a big deal.

I do emphasise this point a bit, arguably to the point of labouring it, but it is entirely fundamental: a great many of these sonnets individually, but most importantly the entire relationship between Shakespeare and his young lover only make sense if we think of William Shakespeare as someone who sees himself past his prime. The great irony is of course that as a playwright he is at this stage only just about to enter the period of his greatest achievements, but he clearly does not know, not even really sense that. What he senses is that he is old and that this man whom he feels a great love and consuming passion for, by contrast, is at his peak. And yet, the difference in age between them cannot be more than about ten to twelve years. For us today, this is hard to comprehend: not only do we not see thirty as anything resembling old, we also don't see all that much of a difference between a 21 year old and a 31 year old. For William Shakespeare there is a world between them.

Not as big a world though, as there is in terms of status. This is the second notion we have not so much revealed here as confirmed: the young man, in every way conceivable, inhabits a different social sphere to that of William Shakespeare. His beauty and his wit could come from anywhere, but his birth – for which read birthright and class – and his wealth are clearly put in his cradle by his parentage. Which is exactly what we've been thinking all along: every indication we have had so far has pointed us to an extraordinarily well-situated English nobleman. You will find people arguing that some of these sonnets are so candid in tone and take such a dim view of some of the things that the young man does that they couldn't possibly be addressed to someone as exalted as the Third Earl of Southampton, or the Third Earl of Pembroke, for that matter, but time and again, and here in Sonnet 37 too, Shakespeare leaves little doubt that he is talking directly to someone who is essentially out of his league.

And the third element that we see again not newly uncovered so much as bedding down into our arrangement of facts and, by the absence of knowable, provable facts, plausible fabrications or conjectures, is that Shakespeare is in fact in love. It is worth every so often reminding ourselves just how extraordinary these sonnets really are. Because yes, it is true: romantic relationships between men are not as unusual in Elizabethan England as all that, and yes, the sonnet is by origin a format devised for the communication of love, and yes in Shakespeare's day the word 'love' may entail a wide spectrum of affection, devotion, loyalty, friendship, kinship, or a meeting of hearts and minds, but here a man is pouring into verse his love for another man at a time when there is simply no framework for celebrating such a love between men and when – though this, to be sure, happens extremely rarely even in Elizabethan England – men can be, and are, tortured to death for the physical expression of this kind of love. And so Sonnet 37, even if at first glance it may not seem particularly noteworthy, turns out to be entirely worth taking note of.

The thematic detour Shakespeare has either embarked, or the first editor of his sonnets has sent us off, on continues with two poems that shed yet more clarifying light on our poet and his young lover, before we then return to the young lover's deeds and misdemeanours that have so upset our poet...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!