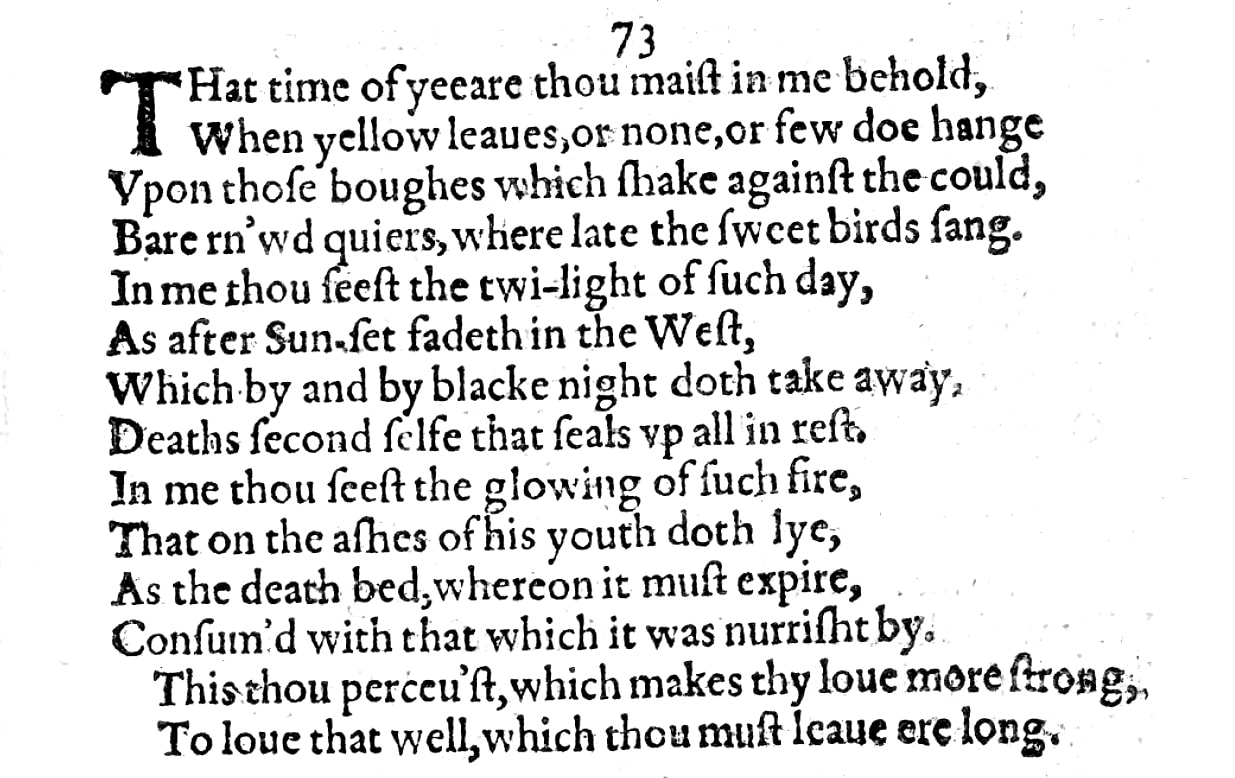

Sonnet 73: That Time of Year Thou Mayst in Me Behold

|

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self that seals up all in rest; In me thou seest the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the deathbed whereon it must expire, Consumed with that which it was nourished by. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. |

|

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, |

You find me in the autumn of my life: what you see in me is the time of year when there are no more leaves, or only a few, or some yellow ones that hang on the branches which shake against the cold air of this late season, soon to be eclipsed by winter...

|

|

Bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.

|

...and these branches or boughs are like the empty choirs of derelict churches where once upon a time the lovely birds of spring sang their life-affirming song.

This is a particularly evocative poetic triple metaphor: the autumn serves as a metaphor for the late stage in my life, the tree serves as a metaphor for autumn, and the choir sections of churches serve as a metaphor for the branches on which the birds come to sit and sing with their voices pure as those of choir boys. Where William Shakespeare gets his image of the derelict churches from we can't say with certainty, but editors point to the large number of churches, abbeys, and chapels in England that were left abandoned after the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth I's father, who instigated the English Reformation and instituted the Church of England so he could annul his marriage with Catherine of Aragon, the first of his ultimately six wives. In other words: the country in which Shakespeare grew up would have been littered with such buildings left to crumble and decay. |

|

In me thou seest the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west, |

I am in the evening of my life: what you see in me are those fading twilight hours that coincide with the sun having set in the west.

The 'such' here refers to the time of day, rather than to the day itself, as we might be tempted to interpret it. This is not about such a day when this happens, because this happens every day, but it is about such a time of day when this happens. |

|

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self that seals up all in rest. |

And this twilight, now fading, is gradually taken away by black night, which is like a second self to death, as it similarly seals everything up in rest.

The obvious difference between death and the night, one might argue, is that night passes and the creatures and humans who have gone to sleep in the evening wake up again in the morning, but when the day is seen as a metaphor for our cycle of life, then that life ends with the night, as a new dawn would be the beginning of a new life, which in some religions would constitute a reincarnation, or, in the traditional Christian faith, might correspond to a resurrection or possibly the calling of the dead souls before God on Judgment Day. But the reason why the night is death's second self is that to the day of life, night is death. And to understand the power of this image, it is worth bringing to mind once more just how dark a night in Elizabethan England would be: with no electricity, no street lighting, and no building taller than a church, so no windows lit high above the ground, there was no light pollution to speak of. From about eleven or midnight onwards in a small town or village, the only light at night would come from the moon, and so a moonless night would be pitch black and very quiet and restful indeed. |

|

In me thou seest the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, |

I am at the fading embers of my life. What you see in me is the final glow of a fire that has burnt up the energy, the power of his youth; I lie on the ashes of this conflagration...

|

|

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by. |

...and these ashes are like a deathbed on which I soon must expire and die, consumed by the same force which had previously nourished me: life itself.

|

|

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long. |

This is what you see when you look at me, which makes your love even stronger, so that you can love that person well whom you must leave before long.

There are several striking facets to this gorgeous conclusion: Firstly, the sentence comes along as a statement of fact: there is no question mark at the end. It is possible, of course, that this is a mistake, but the way the sonnet is followed by Sonnet 74 makes this improbable. It is extremely likely that Shakespeare deliberately phrases this as a statement. But we have often now got the impression that there may be more than a hint of wishful thinking to these expressions of love on behalf of the young man. Still, for William Shakespeare to write to the poem's recipient in a direct address with such confidence and also – as the next sonnet will demonstrate – care may suggest that he has had reassurance of love from the young lover, perhaps in response to the previous couple or batch, and that would make this a really rather moving moment. The sentence also suggests that the young lover will soon have to leave that which he loves well now, namely Shakespeare. This is not what happens when an older lover dies: we would ordinarily then speak of the deceased as having gone and left the other person behind. Whether or not this is of significance, we can't say, but we are heading towards a period in the relationship between the young man and William Shakespeare where the young man's obligations to his title, his status, and his family name make it unavoidable that he marry and have children before long, and so it is possible that Shakespeare anticipates such an outcome with this couplet. And it has also been suggested that the curiously and conspicuously placed 'well' might just be a pun by Will on his own name. He puns extensively, almost excessively, one might say, on his name later in the series – albeit not ordinarily with the word 'well', but with any number of meanings of 'will' – and so this, while it would be unusual, can't be entirely ruled out here. |

Sonnet 73 is the first in a second pair of poems that meditate on the poet's age and mortality and reflect on the purpose of his very existence, But while Sonnets 71 & 72 focus on Shakespeare's reputation, which he perceives as poor and which he therefore fears might also tarnish the young man were he to show his love and mourning for Shakespeare after his death, Sonnet 73 concentrates on the wondrous realisation – or possibly hope – that in spite of Shakespeare's age and although he is approaching what he believes to be his latter years, the young man not only continues to love him, but appears to appreciate both the need and the opportunity to do so before they must eventually part. Sonnet 74 then continues this thought and seeks to reassure the young man that although he will in time see his lover 'shuffle off his mortal coil' – as Shakespeare famously puts it in Hamlet – he will still be in possession of the thing that actually matters: the poet's essence or spirit which is contained in his poetry.

As usual, will look at both these poems, Sonnets 73 & 74, together in the next episode, while examining Sonnet 73 in this one.

Sonnet 73 is easily one of my favourite of Shakespeare's sonnets. It unites upon itself everything I love about his language, admire about his insight into what sometimes gets referred to somewhat inadequately but nevertheless appropriately as 'the human condition', and find fascinating about this collection of deeply personal and profoundly revealing poems.

Its structure is elegant and clear: three quatrains that each present a seemingly simple and straightforward metaphor which in each case, although arguably a commonplace, manages to evoke lasting images and the strong sensation of a deeply felt underlying melancholy: we have all heard the latter stages of life described as autumn, we colloquially speak of the 'twilight years', we are familiar with the idea of the flame or fire of life burning out, and yet with each of these, Shakespeare brings out something else, something stronger, something more compelling than just a poetic trope.

A tree standing leafless in the chill grey of an autumn day is one thing, but this metamorphosing then in our minds to the bare, ruined choirs of an abandoned church takes the familiar idea onto an entirely new and elevated level with correspondingly much deeper emotional and cultural implications. Whether we think of them immediately and consciously or indirectly and subconsciously, the choir boys remind us of an innocence and youth that have by necessity been lost, the derelict building of ornamental beauty and ritual that were once synonymous with an untarnished faith, the sweet birds they are then tied back to of the spring we lived through carefree and light of heart.

In a similar way, Shakespeare brings a whole new depth to the idea of evening standing for the later years in life, by reminding us with unflinching candour that the night that invariably follows such an evening is our death, and yet by following and drawing this line of the cycle, he also offers the redeeming thought of there being a 'life after death' or a continuation of the trajectory that yields into something akin to a new dawn.

And in the last line of his third quatrain – note how it is always in fact the fourth line that contains and delivers the critical twist – he acknowledges that that which nourishes us also consumes us, that we can only burn our flame of life by using up our source of sustenance and power, that, while every year renews itself, and so does every day, our living of our lives on earth in our bodies is tied into the entropic laws of biology and physics, which we cannot escape: in order to be we must exhaust ourselves and fade.

The beauty and wisdom of these reflections is then crowned with the closing couplet that also harbours a secret, maybe even a mystery:

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

You see all this in me and are fully aware of where I am at in my life and therefore how far ahead of you in my progression towards death I am, but rather than putting you off or driving you away from me, what this does is make your love for me even stronger, so that you can love that well which you must leave before long.

Why is William Shakespeare phrasing his thought this way? Leaving aside the noteworthy reversal of who will have to leave whom ere long that we observed earlier on, in the light of much of what has gone before, the certainty with which this sentence comes along strikes us as unwarranted, and so our first reaction may be: is this just wishful thinking? The impression we have gained so far of the young man – and as you will know if you've been listening to this podcast, there really is no good reason why we should not continue to think of this person whom these sonnets so far have been written to and about as one and the same young man – is that he is fickle, full of himself, and unfaithful.

But here it may help us to bear in mind the effervescent nature of these lives and therefore these relationships, and the most pertinent of these descriptions in this context may well be 'fickle'. Yes, this young man has been unfaithful, of that we can be sure; yes, he is certainly full of himself, we have plenty of circumstantial evidence to believe so; but most relevant may well be that he is also fickle. That he blows hot and cold. That he can be dismissive of our poet and betray him, put him in his place and demand better of him, but that he can also be and show that he is in love. That he cares deeply for Shakespeare, no matter what. That he needs a lot of attention and reassurance and massaging of his ego, but that when he sees his poet sad and dejected he comes to him to reassure, to comfort, to love. Do we know this to be the case? Of course not. But if – as once or twice on previous occasions we found good reason to do – we allow for the possibility of these sonnets being part of a conversation that takes place partly in person, partly in writing, partly perhaps in letters we don't have, partly certainly inside these sonnets, then all we have to imagine is the young man saying or writing something to Shakespeare that we don't hear or possess on paper any longer that says to him, in his own words at the time: Will. You are not worthless. Forget those people who mock you. Your work doesn't shame you, it's glorious. Don't pay heed to the idiots who don't get you: you are far better a poet than all of them put together. I can see that. And don't fret about your age, you're not even thirty. You're meant to have another forty years in you yet. Things will happen for you. And I love you.

And if you wonder, about the number 30 in there and think, really? He's not even thirty? Then yes, of this we can be pretty certain. And we discuss this in a bit of detail in the episodes covering Sonnets 25, 37, 60, and 62, so I won't be going into it any further here, suffice it to say that if you survived beyond the age of thirty as a man in London, you did reasonably well.

Are we speculating if we suggest that words to this or a similar effect may have been expressed by the young lover. Of course we are. Is this speculation wild and unreasonable? Not really: these are human beings. They love. They argue. They experience the highs and lows of living. They talk to each other. Probably more than we talk to each other today, because they have no social media and no messaging services. They have to either talk to each other face to face or write to each other. Imagining what the young man may have said or written does not prove anything to us but it easily makes sense of what we have in front of us of Shakespeare's and we don't have to fetch far for this: two people in the kind of relationship that we are getting an ever clearer picture of could easily and without contrivance be in just such a kind of ongoing dialogue.

And Sonnet 74, which follows on from Sonnet 73 directly, fits the notion of such an exchange rather perfectly...

As usual, will look at both these poems, Sonnets 73 & 74, together in the next episode, while examining Sonnet 73 in this one.

Sonnet 73 is easily one of my favourite of Shakespeare's sonnets. It unites upon itself everything I love about his language, admire about his insight into what sometimes gets referred to somewhat inadequately but nevertheless appropriately as 'the human condition', and find fascinating about this collection of deeply personal and profoundly revealing poems.

Its structure is elegant and clear: three quatrains that each present a seemingly simple and straightforward metaphor which in each case, although arguably a commonplace, manages to evoke lasting images and the strong sensation of a deeply felt underlying melancholy: we have all heard the latter stages of life described as autumn, we colloquially speak of the 'twilight years', we are familiar with the idea of the flame or fire of life burning out, and yet with each of these, Shakespeare brings out something else, something stronger, something more compelling than just a poetic trope.

A tree standing leafless in the chill grey of an autumn day is one thing, but this metamorphosing then in our minds to the bare, ruined choirs of an abandoned church takes the familiar idea onto an entirely new and elevated level with correspondingly much deeper emotional and cultural implications. Whether we think of them immediately and consciously or indirectly and subconsciously, the choir boys remind us of an innocence and youth that have by necessity been lost, the derelict building of ornamental beauty and ritual that were once synonymous with an untarnished faith, the sweet birds they are then tied back to of the spring we lived through carefree and light of heart.

In a similar way, Shakespeare brings a whole new depth to the idea of evening standing for the later years in life, by reminding us with unflinching candour that the night that invariably follows such an evening is our death, and yet by following and drawing this line of the cycle, he also offers the redeeming thought of there being a 'life after death' or a continuation of the trajectory that yields into something akin to a new dawn.

And in the last line of his third quatrain – note how it is always in fact the fourth line that contains and delivers the critical twist – he acknowledges that that which nourishes us also consumes us, that we can only burn our flame of life by using up our source of sustenance and power, that, while every year renews itself, and so does every day, our living of our lives on earth in our bodies is tied into the entropic laws of biology and physics, which we cannot escape: in order to be we must exhaust ourselves and fade.

The beauty and wisdom of these reflections is then crowned with the closing couplet that also harbours a secret, maybe even a mystery:

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

You see all this in me and are fully aware of where I am at in my life and therefore how far ahead of you in my progression towards death I am, but rather than putting you off or driving you away from me, what this does is make your love for me even stronger, so that you can love that well which you must leave before long.

Why is William Shakespeare phrasing his thought this way? Leaving aside the noteworthy reversal of who will have to leave whom ere long that we observed earlier on, in the light of much of what has gone before, the certainty with which this sentence comes along strikes us as unwarranted, and so our first reaction may be: is this just wishful thinking? The impression we have gained so far of the young man – and as you will know if you've been listening to this podcast, there really is no good reason why we should not continue to think of this person whom these sonnets so far have been written to and about as one and the same young man – is that he is fickle, full of himself, and unfaithful.

But here it may help us to bear in mind the effervescent nature of these lives and therefore these relationships, and the most pertinent of these descriptions in this context may well be 'fickle'. Yes, this young man has been unfaithful, of that we can be sure; yes, he is certainly full of himself, we have plenty of circumstantial evidence to believe so; but most relevant may well be that he is also fickle. That he blows hot and cold. That he can be dismissive of our poet and betray him, put him in his place and demand better of him, but that he can also be and show that he is in love. That he cares deeply for Shakespeare, no matter what. That he needs a lot of attention and reassurance and massaging of his ego, but that when he sees his poet sad and dejected he comes to him to reassure, to comfort, to love. Do we know this to be the case? Of course not. But if – as once or twice on previous occasions we found good reason to do – we allow for the possibility of these sonnets being part of a conversation that takes place partly in person, partly in writing, partly perhaps in letters we don't have, partly certainly inside these sonnets, then all we have to imagine is the young man saying or writing something to Shakespeare that we don't hear or possess on paper any longer that says to him, in his own words at the time: Will. You are not worthless. Forget those people who mock you. Your work doesn't shame you, it's glorious. Don't pay heed to the idiots who don't get you: you are far better a poet than all of them put together. I can see that. And don't fret about your age, you're not even thirty. You're meant to have another forty years in you yet. Things will happen for you. And I love you.

And if you wonder, about the number 30 in there and think, really? He's not even thirty? Then yes, of this we can be pretty certain. And we discuss this in a bit of detail in the episodes covering Sonnets 25, 37, 60, and 62, so I won't be going into it any further here, suffice it to say that if you survived beyond the age of thirty as a man in London, you did reasonably well.

Are we speculating if we suggest that words to this or a similar effect may have been expressed by the young lover. Of course we are. Is this speculation wild and unreasonable? Not really: these are human beings. They love. They argue. They experience the highs and lows of living. They talk to each other. Probably more than we talk to each other today, because they have no social media and no messaging services. They have to either talk to each other face to face or write to each other. Imagining what the young man may have said or written does not prove anything to us but it easily makes sense of what we have in front of us of Shakespeare's and we don't have to fetch far for this: two people in the kind of relationship that we are getting an ever clearer picture of could easily and without contrivance be in just such a kind of ongoing dialogue.

And Sonnet 74, which follows on from Sonnet 73 directly, fits the notion of such an exchange rather perfectly...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!