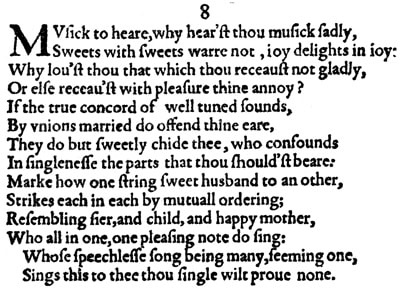

Sonnet 8: Music to Hear, Why Hearst Thou Music Sadly?

|

Music to hear, why hearst thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy: Why lovest thou that which thou receivest not gladly, Or else receivest with pleasure thine annoy? If the true concord of well-tuned sounds, By unions married, do offend thine ear, They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear. Mark how one string, sweet husband to another, Strikes each in each by mutual ordering, Resembling sire, and child, and happy mother, Who all in one one pleasing note do sing, Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one, Sings this to thee: thou single wilt prove none. |

|

Music to hear, why hearst thou music sadly?

|

You, who are like music to one's ears – harmonious, beautiful, delightful – why are you yourself sad when 'hearing music'?

Music of course is a metaphor: the young man is likened to a beautiful piece of music, which is something pleasant to be in the presence of, and asked why he appears to be sad when 'hearing music', in other words being in the presence of something that is meant to be in equal measure pleasant. |

|

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy:

|

Sweet, lovely things do not fight with other sweet and lovely things – "war" is a verb here: they do not war – and anything that is joyful, such as you are, will naturally delight in anything else that is joyful.

|

|

Why lovest thou that which thou receivest not gladly,

Or else receivest with pleasure thine annoy. |

Why do you not gladly or happily love what you receive, but in fact take pleasure in receiving that which annoys or bores or even actually harms you.

The "or else" here has the function of an 'and', and seems to be amplifying this, as in 'and, even worse', while "thine annoy" is that which generally vexes or annoys, or here more specifically damages or harms you. The young man is asked why he rejects that which he is offered to receive and instead readily receives that which is bad for him. The suggestion very clearly being that we are not talking about objects here but about people, which would imply that the young man in question is refusing potential partners – as in: prospective wives – who are being proposed to him, while at the same time indulging in encounters with people who might be deemed damaging to him in one way or another. |

|

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear, |

And here we get a clearer indication of this. Still using the metaphor of music, the poet tells the young man that if he is offended by the "sounds" – for which here read the idea or the prospect on the one hand, but also the talk – of a harmonious marriage offends him...

PRONUNCIATION: Note that tuned here has two syllables: tu-nèd. |

|

They do but sweetly chide thee who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear. |

...then these sounds – that's where the talk comes in – do only gently admonish you, who defies the role in life that you should be playing.

We've had 'confound' in Sonnet 5 where "...never resting Time leads Summer on / To hideous Winter and confounds him there," meaning defeats or destroys him. Here, similarly, the young man is told that he goes against and effectively ruins the family life he is meant to lead by remaining single. |

|

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering, |

The musical metaphor continues and now invokes a stringed instrument, such as a lute, for example, where the way the individual strings are tuned is such that they stand in an again harmonious relationship to each other...

|

|

Resembling sire and child and happy mother

Who all in one one pleasing note do sing, |

...and these strings are not unlike a family with father – sire – child and the happy mother, who all together produce one pleasing note or chord...

|

|

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one

|

...which is like a song without words and which, although it is generated by several elements – the father, mother and child above – seems to be of one voice that...

|

|

Sings this to thee: thou single wilt prove none.

|

...sings to you: if you remain single you will end up being nobody because you will be undone.

|

Sonnet 8 makes yet another, maybe somewhat more laboured, attempt at coming up with a metaphor to move the young man to making a child: namely music. And it does offer up a significant new revelation, as we shortly shall see...

The poet, William Shakespeare, first wonders why the young man who is himself so lovely seems to reject loveliness, when all things lovely should be in harmony with each other and rejoice in each other's presence, and asks him directly why he will refuse to love that which is on offer, while instead finding pleasure in that which is harmful to him.

It remains for us to wonder what or, more to the point, whom precisely Shakespeare has in mind here, but in the context of these first few sonnets it is not so difficult to speculate. This is the eighth iteration of essentially the same message – or the seventh if we count Sonnets 5 and 6 as one: get married and have children! So "that which thou receivest" is unlikely to be a chocolate mousse. It is very likely to be a bride, and if it is one that the young man 'receives', then that would strongly suggest a potential wife who has been chosen for him.

We have noted before that marriage in Shakespeare's day more often than not is really quite transactional; and partly or fully arranged marriages are absolutely the norm, as the marriage really has to make sense economically and socially much more than it has to fulfil the love or desire of either of the two people getting married. The whole reason why Romeo and Juliet works as a romantic tragedy is because Juliet is from the outset betrothed to Paris who is deemed much more suitable for her as a Capulet than any member of the feuding Montague family could ever be. And if this is the case, if the recipient of these sonnets is rejecting proposed potential brides, then it gives us a further significant pointer towards his potential identity; it would suggest strongly that we are looking for someone who is not only told to marry, but also whom!

And that makes this the most revealing quatrain – set of four lines – of this sonnet. We now know that our young man is:

- beautiful and considered to be beautiful

- of some status and therefore known to his world

- most likely a first born or only son

- the mirror image or at least bearing a striking resemblance to his mother

- obstinate in his refusal to marry

- and specifically also rejecting the bride or brides who is or who are being proposed to him

Who or what "thine annoy" is, meanwhile, also of course remains open to speculation. But again, in the given context there are not all that many options. To work as a proper juxtaposition to a young woman chosen for him by somebody else, such as a concerned parent or guardian, the "annoy" is unlikely to be a skateboard. Not only because skateboards weren't invented then, but also because we are looking for something the young man could be receiving with pleasure in an amorous or sexual or at the very least sensual setting, and that would either be:

a) one or several unsuitable women – possibly of 'loose character' – whom he has no intention to marry

b) one or several people of any gender who offer 'pleasure' as a professional service and who are therefore not eligible for marriage

c) one or several men - be they suitable or no – whom he has no ability to marry, because equal marriage as a concept will not exist for a good four hundred years yet, or

d) any combination of the above

We don't know which applies, but what we do know is that the poet tells the young nobleman to stop whatever he is doing and instead think of a musical instrument and listen to how harmoniously the strings play together to demonstrate to him how he is undoing himself by staying single.

Wherein, as it happens, lies another logical flaw in the poet's thinking, we could argue. Either that, or quite possibly a deliberate contradiction that rather undermines the argument. Because, no matter how "sweetly" these "well-tuned sounds" chide, their "speechless song" must by now surely grate on the young man. If you are 19, 20, thereabouts, wealthy and handsome and getting a good deal of pleasure from your supposed 'annoy', and you keep being told it's time to get married, then even the most dulcet tones will surely start to get on your nerves...

And here lies another point of potentially great interest to this Sonnet 8: if you get the impression that maybe William Shakespeare is here being just ever so slightly facetious, perhaps just a tad insincere, you could be forgiven. We cannot precisely pinpoint what causes this effect, but Shakespeare knows how to write truth when he wants to write truth and it then comes across with weight and power. This sonnet is disconcertingly lightweight in both its argument and its tone. It sounds almost as if I, the poet, were here somewhat going through the motions and telling the young man, almost with a wink: you know as well as I know that what I am writing here is, if not nonsense, then more or less tedious and by now surplus to requirement. You get the message, there are only so many ways of saying it, here's another one, I don't really expect you to take this any more seriously than I do.

We don't know whether that's the case, it is just an impression that we might get, and what supports this notion that Shakespeare isn't perhaps being entirely convincing here is that as he is writing this, he is living in London, far from his own wife and children, and he is either already or will soon to be engaging in pleasures that someone might feel fairly inclined to describe as his 'annoy', at some point, before too long, as we shall see, even he himself. And if that is the case, if the poet's heart here really isn't strictly in it, then that in turn further supports our idea – aired a couple of times now – that very possibly these first few sonnets in the collection are simply a writing job that Shakespeare has accepted and therefore has to carry out in a plausibly poetic way. And after all, for all its real or perceived shortcomings, Sonnet 8 is certainly plausibly poetic.

Whether any of this is as we here are inclined to suggest, we don't know. Certainly not for certain. But – most fortuitously – we will get further and stronger pointers fairly soon...

The poet, William Shakespeare, first wonders why the young man who is himself so lovely seems to reject loveliness, when all things lovely should be in harmony with each other and rejoice in each other's presence, and asks him directly why he will refuse to love that which is on offer, while instead finding pleasure in that which is harmful to him.

It remains for us to wonder what or, more to the point, whom precisely Shakespeare has in mind here, but in the context of these first few sonnets it is not so difficult to speculate. This is the eighth iteration of essentially the same message – or the seventh if we count Sonnets 5 and 6 as one: get married and have children! So "that which thou receivest" is unlikely to be a chocolate mousse. It is very likely to be a bride, and if it is one that the young man 'receives', then that would strongly suggest a potential wife who has been chosen for him.

We have noted before that marriage in Shakespeare's day more often than not is really quite transactional; and partly or fully arranged marriages are absolutely the norm, as the marriage really has to make sense economically and socially much more than it has to fulfil the love or desire of either of the two people getting married. The whole reason why Romeo and Juliet works as a romantic tragedy is because Juliet is from the outset betrothed to Paris who is deemed much more suitable for her as a Capulet than any member of the feuding Montague family could ever be. And if this is the case, if the recipient of these sonnets is rejecting proposed potential brides, then it gives us a further significant pointer towards his potential identity; it would suggest strongly that we are looking for someone who is not only told to marry, but also whom!

And that makes this the most revealing quatrain – set of four lines – of this sonnet. We now know that our young man is:

- beautiful and considered to be beautiful

- of some status and therefore known to his world

- most likely a first born or only son

- the mirror image or at least bearing a striking resemblance to his mother

- obstinate in his refusal to marry

- and specifically also rejecting the bride or brides who is or who are being proposed to him

Who or what "thine annoy" is, meanwhile, also of course remains open to speculation. But again, in the given context there are not all that many options. To work as a proper juxtaposition to a young woman chosen for him by somebody else, such as a concerned parent or guardian, the "annoy" is unlikely to be a skateboard. Not only because skateboards weren't invented then, but also because we are looking for something the young man could be receiving with pleasure in an amorous or sexual or at the very least sensual setting, and that would either be:

a) one or several unsuitable women – possibly of 'loose character' – whom he has no intention to marry

b) one or several people of any gender who offer 'pleasure' as a professional service and who are therefore not eligible for marriage

c) one or several men - be they suitable or no – whom he has no ability to marry, because equal marriage as a concept will not exist for a good four hundred years yet, or

d) any combination of the above

We don't know which applies, but what we do know is that the poet tells the young nobleman to stop whatever he is doing and instead think of a musical instrument and listen to how harmoniously the strings play together to demonstrate to him how he is undoing himself by staying single.

Wherein, as it happens, lies another logical flaw in the poet's thinking, we could argue. Either that, or quite possibly a deliberate contradiction that rather undermines the argument. Because, no matter how "sweetly" these "well-tuned sounds" chide, their "speechless song" must by now surely grate on the young man. If you are 19, 20, thereabouts, wealthy and handsome and getting a good deal of pleasure from your supposed 'annoy', and you keep being told it's time to get married, then even the most dulcet tones will surely start to get on your nerves...

And here lies another point of potentially great interest to this Sonnet 8: if you get the impression that maybe William Shakespeare is here being just ever so slightly facetious, perhaps just a tad insincere, you could be forgiven. We cannot precisely pinpoint what causes this effect, but Shakespeare knows how to write truth when he wants to write truth and it then comes across with weight and power. This sonnet is disconcertingly lightweight in both its argument and its tone. It sounds almost as if I, the poet, were here somewhat going through the motions and telling the young man, almost with a wink: you know as well as I know that what I am writing here is, if not nonsense, then more or less tedious and by now surplus to requirement. You get the message, there are only so many ways of saying it, here's another one, I don't really expect you to take this any more seriously than I do.

We don't know whether that's the case, it is just an impression that we might get, and what supports this notion that Shakespeare isn't perhaps being entirely convincing here is that as he is writing this, he is living in London, far from his own wife and children, and he is either already or will soon to be engaging in pleasures that someone might feel fairly inclined to describe as his 'annoy', at some point, before too long, as we shall see, even he himself. And if that is the case, if the poet's heart here really isn't strictly in it, then that in turn further supports our idea – aired a couple of times now – that very possibly these first few sonnets in the collection are simply a writing job that Shakespeare has accepted and therefore has to carry out in a plausibly poetic way. And after all, for all its real or perceived shortcomings, Sonnet 8 is certainly plausibly poetic.

Whether any of this is as we here are inclined to suggest, we don't know. Certainly not for certain. But – most fortuitously – we will get further and stronger pointers fairly soon...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!