Sonnet 3: Look in Thy Glass and Tell the Face Thou Viewest

|

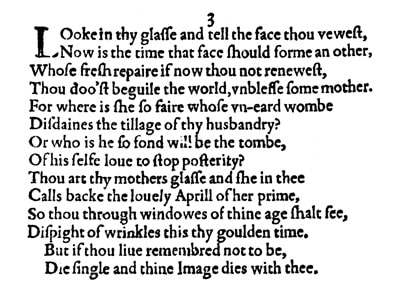

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,

Now is the time that face should form another, Whose fresh repair, if now thou not renewest, Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother. For where is she so fair, whose uneared womb Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry? Or who is he so fond, will be the tomb Of his self-love, to stop posterity? Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee Calls back the lovely April of her prime, So thou, through windows of thine age shalt see, Despite of wrinkles, this, thy golden time. But if thou live remembered not to be, Die single, and thine image dies with thee. |

|

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,

|

Look into the mirror – "thy glass" – and tell your face – "the face thou viewest"...

|

|

Now is the time that face should form another,

|

...that now is the time that face – yours – should make a new face, meaning create a son,...

|

|

Whose fresh repair, if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother. |

...of whose young and perfect condition – his "fresh repair" – you will deprive the world if you don't renew yourself in this way, and you will make some potential mother of your child unhappy.

This dense couple of lines is a wonderfully Shakespearean example of packing a lot into few words. The sentence structure is in itself an artifice that to us at first may sound a bit challenging, but he does this a lot: take some words as read and jump from one grammatical element to another. Here, he drops the 'Of' which we would expect at the beginning of the sentence and he also melds the two objects: the "fresh repair" through "whose" is linked to "another," which is the new face, the child, but "if now thou not renewest" really refers to the young man himself: he renews himself by producing a child. |

|

For where is she so fair, whose uneared womb

|

Where is the woman – the potential mother – who is so beautiful that her womb, which is as yet "uneared," meaning 'unploughed' or not yet tilled, in other words virginal...

|

|

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry,

|

...would reject you as the man giving her a child.

The imagery of a field being ploughed and seeded is quite graphic and it is interesting to note that Shakespeare here focuses entirely on the planting of a seed to grow an heir, rather than, say, on being a 'good husband' and living partner to his potential future wife, in the sense we would understand it today: 'uneared', 'tillage', and 'husbandry' are all terms from farming. |

|

Or who is he so fond, will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity. |

Or who is the man who is so foolish – "fond" often in Shakespeare has this meaning – that he will turn himself into the tomb of his self-love, either with the direct purpose or in any case with the effect of ending his line of succession.

This is the strongest indication yet that we have that the young man's lineage is dependent on him. His 'posterity', and therefore his name and the continued existence of his family's future will cease if he dies childless. |

|

Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime; |

You are a mirror to your mother and thus also the mirror image of your mother, and when she looks at you she recalls and remembers her own youth, the April or springtime of her prime.

This is one of the most significant couple of lines we have encountered so far, as we shall see. |

|

So thou, through windows of thine age shalt see

Despite of wrinkles this, thy golden time. |

And in the same way that your mother in her now advanced years remembers her youth by looking at you, so you through your eyes when you are of an advanced age – the "windows of thine age" – will be able to look back on this time in your life, which is your prime, even though you will by then have the wrinkles of old age.

'Windows' as a metaphor for 'eyes' is one that Shakespeare uses repeatedly, and it is not one that is alien to us: we still use the expression 'windows to your soul', for example, meaning the eyes. |

|

But if thou live, remembered not to be

Die single, and thine image dies with thee. |

But if you live in a way that creates no memory of you – the memory here being the child or children of course – then live as a single man and die as a single man, and that means that your image, your beauty, will be lost forever.

|

Sonnet 3 is incredibly exciting, because here we learn something genuinely significant and specific and new.

The overall message is not new: the sonnet finds another way to tell the young man that it is time for him to produce a son and it does this by invoking the image of the mirror: look into the mirror and tell yourself it's time to have children so that these children who become a mirror of you will then allow you to remember your own youth through looking at them. So far, so straightforward.

What tells us something relevant and pertinent are the first two lines of the third quatrain:

Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime

"Thou art thy mother's glass." Not 'thy father's'. You look like your mother. Not like your father. William Shakespeare is the greatest writer in the English language that ever lived: had he wanted to say to the young man that he resembles his father – as many young men do, and as indeed he predicts the young man's son will in good time – he would have been able to do so. He could just as easily have written:

Thou art thy father's glass, and he in thee

Calls back the lovely April of his prime

Though granted the word 'lovely' here would have been unusual in the context of a man and father at the time. But Shakespeare would have found another adjective that scans, and if anything this also quite effectively rules out the chance of this just being a misprint or transcription error.

William Shakespeare is pointing out the fact that whoever this young man is, he bears a resemblance to his mother. This is a highly unusual and specific thing to do, especially in a patriarchal society like Shakespeare's. The 'normal' or 'expected' thing would be for the poet to say how much the young man resembles his father. This begs the question: why? Why would the poet choose to do this? The obvious answers that offer themselves are:

- The young man really has an unusually striking resemblance to his mother which is so eye-catching that it is more noteworthy than any resemblance he might bear to his father; or

- The young man doesn't have a father; or

- Quite conceivably both.

Sonnet 3 doesn't give us the reason, and any conclusion we might draw from this sonnet alone would almost certainly be premature. But it's a fascinating snippet of evidence that we can put to one side and say: let's hold on to this and see if there is anything else in these sonnets that adds to it and may help us form a clearer picture. And as you can maybe guess, most fortuitously, there will be...

The overall message is not new: the sonnet finds another way to tell the young man that it is time for him to produce a son and it does this by invoking the image of the mirror: look into the mirror and tell yourself it's time to have children so that these children who become a mirror of you will then allow you to remember your own youth through looking at them. So far, so straightforward.

What tells us something relevant and pertinent are the first two lines of the third quatrain:

Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime

"Thou art thy mother's glass." Not 'thy father's'. You look like your mother. Not like your father. William Shakespeare is the greatest writer in the English language that ever lived: had he wanted to say to the young man that he resembles his father – as many young men do, and as indeed he predicts the young man's son will in good time – he would have been able to do so. He could just as easily have written:

Thou art thy father's glass, and he in thee

Calls back the lovely April of his prime

Though granted the word 'lovely' here would have been unusual in the context of a man and father at the time. But Shakespeare would have found another adjective that scans, and if anything this also quite effectively rules out the chance of this just being a misprint or transcription error.

William Shakespeare is pointing out the fact that whoever this young man is, he bears a resemblance to his mother. This is a highly unusual and specific thing to do, especially in a patriarchal society like Shakespeare's. The 'normal' or 'expected' thing would be for the poet to say how much the young man resembles his father. This begs the question: why? Why would the poet choose to do this? The obvious answers that offer themselves are:

- The young man really has an unusually striking resemblance to his mother which is so eye-catching that it is more noteworthy than any resemblance he might bear to his father; or

- The young man doesn't have a father; or

- Quite conceivably both.

Sonnet 3 doesn't give us the reason, and any conclusion we might draw from this sonnet alone would almost certainly be premature. But it's a fascinating snippet of evidence that we can put to one side and say: let's hold on to this and see if there is anything else in these sonnets that adds to it and may help us form a clearer picture. And as you can maybe guess, most fortuitously, there will be...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!