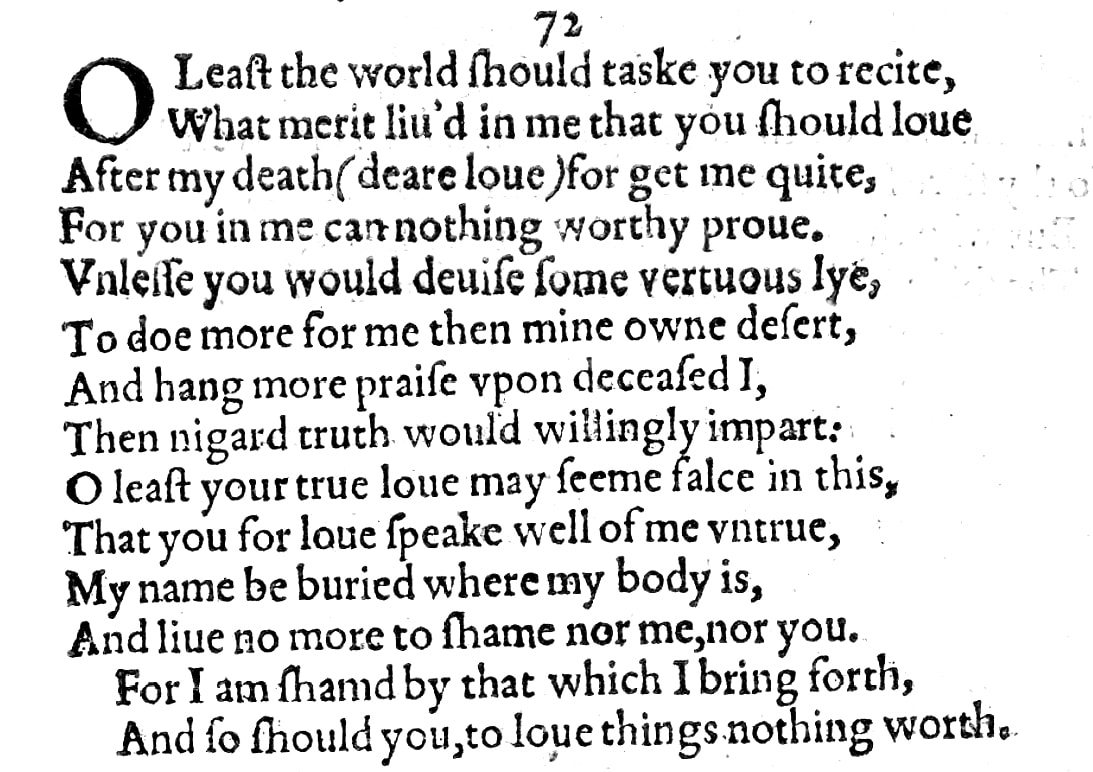

Sonnet 72: O Lest the World Should Task You to Recite

|

O lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me that you should love After my death, dear love, forget me quite, For you in me can nothing worthy prove, Unless you would devise some virtuous lie To do more for me than mine own desert And hang more praise upon deceased I Than niggard truth would willingly impart. O lest your true love may seem false in this That you for love speak well of me untrue, My name be buried where my body is And live no more to shame nor me nor you, For I am shamed by that which I bring forth And so should you, to love things nothing worth. |

|

O lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me that you should love |

The poem continues the argument from the previous one and further expounds:

O, so as to avoid that the world should give you the task of listing or naming what qualities I had that were deserving of your love when I was alive... This is the same world as the one to which Shakespeare, to us somewhat dubiously, gave the epithet 'wise' in Sonnet 71; and although we wondered then whether we can take him seriously when he refers to a world that mocks him by this adjective, the now anticipated line of query by this same world is in keeping with how he experiences it: this world of which he speaks would only task the young man with reciting what merit worthy of love lived in Shakespeare, if it couldn't think of any by itself, and so the sense we get of a poet who is not appreciated by his world strongly persists. |

|

After my death, dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove |

After my death, dear love, forget me completely, because there is nothing about me that you can prove to have any worth at all, and so there is nothing that is worthy of your love...

This again sounds more like a view the world may hold, or, to be more precise, a view that Shakespeare perceives the world as holding about him, because it is obvious from many of the other sonnets and from the fact alone that he keeps writing them, as well as his plays, as well as his long narrative poems, that Shakespeare does not truly believe that there is nothing about him that is worthy of appreciation or love. Still, the tone no longer really strikes us as especially ironic; more, perhaps sarcastic, and that makes the direct address to the young man with 'dear love' particularly eye-catching, because we have really no reason to believe that that, at least, is not absolutely sincere, or at any rate that Shakespeare does not still want this to be the case: for his young man to be his dear love. Both John Kerrigan in the Penguin and Colin Burrow in the Oxford Edition of The Sonnets point out that the Quarto Edition has no comma after 'love' in the line preceding these two and recommend that this be honoured: What merit lived in me that you should love After my death, dear love, forget me quite, This allows for the line to be read in two ways, either as above: 'lest you should be tasked to name what qualities I had when I was alive that you should love, then, after my death forget me', or as: 'lest you should be tasked to name what qualities I had that you should love even now that I am dead, do now, that I am dead, forget me'. And knowing Shakespeare, it is more than likely that he was going for both meanings at the same time. |

|

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie

To do more for me than mine own desert |

The sentence continues: there is nothing that can prove to be of worth in me, unless you were to devise some virtuous, for which read, well-intentioned lie – perhaps similar to a 'white' lie – which does more for me than I deserve, in other words, unless you were to say things about me that exceed my own merit and achievements...

The 'unless' is a little misleading, because of course a lie is not a proof. 'Unless', strictly speaking should be followed by something that renders the previous statement untrue, such as, unless you were to dig deeper and find a way to show and therefore convince the world that mine is actually the work of a genius. This would preserve the logic of 'you cannot prove anything of me to be worthy, unless...', but, as you will know if you have been listening to this podcast, we need to be lenient with our poet when it comes to logic. |

|

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart. |

...and in doing so, in devising such a well-meaning lie, you would be heaping – as today we colloquially would say – more praise upon me when I am dead than miserly truth would willingly bestow on me.

Here we once more have this for us today alarming word 'niggard', which still has absolutely nothing to do with the racial slur that it sounds like: as explained in the episodes covering Sonnets 1 and 4, a niggard is simply a miser or a mean person, with the adjective usually being 'niggardly', but here 'niggard' itself is used as an adjective to describe truth. The reason that truth is miserly is that it can only ever give praise to the extent that it is actually merited: you cannot truthfully heap praise upon somebody beyond that which they genuinely deserve; doing so would be flattery, and flattery is faint praise indeed. Editors also commonly refer to the practice at the time of hanging written epitaphs upon or into the tombs of the deceased, as happens at the end of Much Ado About Nothing, where in Scene 3 of Act V, Claudio comes to what he believes to be the tomb of Hero, the woman he has loved and then rejected following baseless allegations of her infidelity, and reads an epitaph he has written for her and then hangs it into the vault as part of a ritual he proposes to repeat every year from now on in. As the title of the play suggests, all is not as it seems, and Hero turns out to be alive and well as the plot to undo her reputation has been accidentally but successfully foiled. And incidentally, if you were looking for examples of 'then' being used interchangeably with 'than', as briefly discussed in the last episode, you need look no further: the 'than' in both "than mine own desert" above and "than niggard truth would willingly impart" here in the Quarto Edition is spelt 'then'. |

|

O lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue |

And so for it not to be the case that your true love may appear to be false because you, out of love for me, say things about me that are not true...

After everything that has happened and been said over the last seventy-odd sonnets, we can't help but wonder to what extent this 'true love' of which Shakespeare speaks is indeed true and to what extent he is here still or again expressing something he wishes to be whilst knowing it not to be so. And it is entirely possible that Shakespeare himself wants to lift us onto this conflicted understanding by building into these couple of lines an inherent paradox: A true, as in faithful, love may well feel inclined to speak well of their lover beyond the degree of what miserly truth would strictly allow, which would then make them 'false' in the sense that they are no longer adhering to the truth. And an additional layer of meaning unfolds if we allow for 'love' to be the loved person, in this case Shakespeare: then Shakespeare, who is the 'true love' of the young man becomes 'false' as in 'falsely praised' for the same reason: the love the young man bears Shakespeare. |

|

My name be buried where my body is

And live not more to shame nor me nor you, |

So in order to prevent this from happening, that your true love may appear to be false because you speak well of me, even though there is nothing good that can truthfully be said about me, let my name die with me so it can no longer bring shame upon myself or upon you.

This directly echoes and reinforces the plea from the previous sonnet: do not mourn me, do not say and repeat my name, because the world may mock you if you do, and so let my name die and be forgotten about so it can no longer bring shame upon me and therefore by association you. |

|

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth

And so should you, to love things nothing worth. |

Because I am shamed by the work I produce and put forward, and you will be shamed for loving things that are worth nothing.

Noteworthy here is that in this last line, Shakespeare talks about 'things nothing worth', because this on the one hand draws our attention to the things that Shakespeare brings forth, namely his writing, and it also lumps Shakespeare himself together with his output, because up until now these two sonnets were very much about the young man's love for Shakespeare, but of course a poet and his poetry are inseparable from each other, you cannot appreciate one without the other, and the sting that pierces Shakespeare in these two sonnets is evidently that the world does not appreciate his writing. |

Sonnet 72 picks up on Sonnet 71 and explains why the supposedly 'wise' world would look down on the young man for having loved or for still loving Shakespeare after his death and why he should therefore forget him and allow the poet's name to pass into oblivion, along with his decomposing body in the grave. The sonnet reinforces and intensifies the sense that Shakespeare is or certainly feels unappreciated by the world around him, as he here speaks not only of being 'mocked' by people, but in fact shamed by the work he himself produces.

Together, Sonnets 71 & 72 thus signal a low point in the poet's trajectory, as they very obviously refer to a wider malaise in the writer's career.

Here are the two poems back to back:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell.

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O if, I say, you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love even with my life decay,

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me after I am gone.

O lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me that you should love

After my death, dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove,

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie

To do more for me than mine own desert

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart.

O lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue,

My name be buried where my body is

And live no more to shame nor me nor you,

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

When after Sonnet 71 we were left with an impression that although the mockery of a questionably 'wise' world seemed to genuinely hurt and upset the poet, his overall disposition was one of subtle but still obvious irony, with Sonnet 72 this irony gives way to a wistful sadness. And while we do not know what exactly brings on this sadness – whether it is as specific an incident as the publication of Robert Greene's legendary 'upstart crow' attack of 1592, which we discussed with Sonnets 25 and 66, or a much more generic feeling of being mocked and shamed – what we can sense without having to go into the domain of much speculation is that as far as William Shakespeare is concerned at the time of his writing these two sonnets, he is not feeling good about himself. And the reason for this very obviously has to do with either the relationship to the young man or his professional standing in the world as a writer, or more than likely both, since the two appear at least partly entwined.

This does pose a specific question though that is of relevance to our understanding of our poet: where on this three-dimensional coordinate system should we plot the centre of gravity? Or to put it in somewhat less cryptic terms: what can we read into the closing couplets of these two sonnets which speak of being mocked by the world and being shamed by that which Shakespeare brings forth: is this about these poems alone and therefore should we focus on the relationship status between him and his young lover or can we really infer that there is more amiss in his world and that he is referring to his writing – his plays, his narrative poems – quite generally?

And herein lie two especially valuable keys.

Number one: Sonnet 71 speaks of a 'wise' world that may mock the young man along with the poet, if the young man were to give himself over to displays of grief and lasting affection. This is unambiguously about the world's perception of the poet and, by extension then, of the young man.

The two poems are obviously and clearly paired and the closing couplet of Sonnet 72 similarly makes it explicit that the young man is in danger of being shamed – clearly in the eyes of the same world – by the work that the poet brings forth. Could the world be thus dismissive about these sonnets alone? The sonnets, as we know, are first mentioned by Frances Meres in 1598 as circulating among Shakespeare's 'private friends'. And it is possible that the small world of friends around the poet and his lover whom we do believe to be a young aristocrat and who is therefore likely to be surrounded by other courtiers and noblemen, is by the time Sonnets 71 & 72 come along aware enough of the very personal, even intimate, contents of these poems and beginning to mock the poet for his love and his expression in so many sonnets of this love.

But we know that, as we discussed with Sonnet 66, by the end of 1594 William Shakespeare starts to experience more and more professional success. His troupe of actors turn into the Lord Chamberlain's men, his long dramatic poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece become bestsellers. His plays are performed at court and at the theatre. He is, by then, not shamed by that which he brings forth, quite the opposite, he is increasingly appreciated, even celebrated.

Is it conceivable that despite of this he feels so dejected about a coterie of private friends disparaging his private sonnets to his very private lover whom, after all, never once actually names in all of these poems, that he falls into what we today would call a depression about it? It is possible but really unlikely. And in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. Try to imagine this: you are a writer whose works are performed in front of the Queen, thousands of people flock to the theatre every week to see your plays, and your poetry sells copies so fast, it has to be reprinted within months. Now a few friends around your young, beautiful, rich lover make some snide comments about your personal poems you have written to and for and about him. Does that send you into a tailspin of despair? Not so much: you can brush this off. You can say with ease: look, these sonnets are not for you, I haven't even published them. Some may think, as Meres does when he gets to hear of them, they're 'sugared', but they're really none of anybody's business. The Queen comes to my plays to find merriment and mirth. I have merit.

Around 1592, 93? Different set of circumstances altogether. Not only do we have the very public insult from Robert Greene who is very much part of the established set of university educated writers and could therefore be seen to expressing the opinions of a supposedly 'wise' world, but there is the financial hardship that comes with the theatres having had to close on account of the plague and the absence of any significant breakthrough as a published poet. That would be demoralising and disheartening. That would drive a writer to thinking of himself as worthless. That would make a person approaching thirty in an era when thirty is considered old, especially for a poet, question: what's the point of it all. And here lies the second key, and it is one we have in fact found at least once before: Sonnets 71 & 72 in all but certainty have to have been composed before the end of 1594, because like Sonnet 66, they no longer make much sense thereafter.

And so the question, can these two sonnets be seen as a reflection of a wider crisis in Shakespeare's life may I believe be answered emphatically. Yes. Everything speaks to this, including the sonnets that surround them, most especially Sonnet 66. And Sonnets 73 & 74 will confirm this and shed yet more light on William Shakespeare's state of mind, and not only that, but – and this, as we shall very shortly see, is genuinely significant – they will also show us that Shakespeare himself takes his sonnets absolutely seriously: to him, they are far from worthless, they are of substance.

Together, Sonnets 71 & 72 thus signal a low point in the poet's trajectory, as they very obviously refer to a wider malaise in the writer's career.

Here are the two poems back to back:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell.

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O if, I say, you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love even with my life decay,

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me after I am gone.

O lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me that you should love

After my death, dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove,

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie

To do more for me than mine own desert

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart.

O lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue,

My name be buried where my body is

And live no more to shame nor me nor you,

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

When after Sonnet 71 we were left with an impression that although the mockery of a questionably 'wise' world seemed to genuinely hurt and upset the poet, his overall disposition was one of subtle but still obvious irony, with Sonnet 72 this irony gives way to a wistful sadness. And while we do not know what exactly brings on this sadness – whether it is as specific an incident as the publication of Robert Greene's legendary 'upstart crow' attack of 1592, which we discussed with Sonnets 25 and 66, or a much more generic feeling of being mocked and shamed – what we can sense without having to go into the domain of much speculation is that as far as William Shakespeare is concerned at the time of his writing these two sonnets, he is not feeling good about himself. And the reason for this very obviously has to do with either the relationship to the young man or his professional standing in the world as a writer, or more than likely both, since the two appear at least partly entwined.

This does pose a specific question though that is of relevance to our understanding of our poet: where on this three-dimensional coordinate system should we plot the centre of gravity? Or to put it in somewhat less cryptic terms: what can we read into the closing couplets of these two sonnets which speak of being mocked by the world and being shamed by that which Shakespeare brings forth: is this about these poems alone and therefore should we focus on the relationship status between him and his young lover or can we really infer that there is more amiss in his world and that he is referring to his writing – his plays, his narrative poems – quite generally?

And herein lie two especially valuable keys.

Number one: Sonnet 71 speaks of a 'wise' world that may mock the young man along with the poet, if the young man were to give himself over to displays of grief and lasting affection. This is unambiguously about the world's perception of the poet and, by extension then, of the young man.

The two poems are obviously and clearly paired and the closing couplet of Sonnet 72 similarly makes it explicit that the young man is in danger of being shamed – clearly in the eyes of the same world – by the work that the poet brings forth. Could the world be thus dismissive about these sonnets alone? The sonnets, as we know, are first mentioned by Frances Meres in 1598 as circulating among Shakespeare's 'private friends'. And it is possible that the small world of friends around the poet and his lover whom we do believe to be a young aristocrat and who is therefore likely to be surrounded by other courtiers and noblemen, is by the time Sonnets 71 & 72 come along aware enough of the very personal, even intimate, contents of these poems and beginning to mock the poet for his love and his expression in so many sonnets of this love.

But we know that, as we discussed with Sonnet 66, by the end of 1594 William Shakespeare starts to experience more and more professional success. His troupe of actors turn into the Lord Chamberlain's men, his long dramatic poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece become bestsellers. His plays are performed at court and at the theatre. He is, by then, not shamed by that which he brings forth, quite the opposite, he is increasingly appreciated, even celebrated.

Is it conceivable that despite of this he feels so dejected about a coterie of private friends disparaging his private sonnets to his very private lover whom, after all, never once actually names in all of these poems, that he falls into what we today would call a depression about it? It is possible but really unlikely. And in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. Try to imagine this: you are a writer whose works are performed in front of the Queen, thousands of people flock to the theatre every week to see your plays, and your poetry sells copies so fast, it has to be reprinted within months. Now a few friends around your young, beautiful, rich lover make some snide comments about your personal poems you have written to and for and about him. Does that send you into a tailspin of despair? Not so much: you can brush this off. You can say with ease: look, these sonnets are not for you, I haven't even published them. Some may think, as Meres does when he gets to hear of them, they're 'sugared', but they're really none of anybody's business. The Queen comes to my plays to find merriment and mirth. I have merit.

Around 1592, 93? Different set of circumstances altogether. Not only do we have the very public insult from Robert Greene who is very much part of the established set of university educated writers and could therefore be seen to expressing the opinions of a supposedly 'wise' world, but there is the financial hardship that comes with the theatres having had to close on account of the plague and the absence of any significant breakthrough as a published poet. That would be demoralising and disheartening. That would drive a writer to thinking of himself as worthless. That would make a person approaching thirty in an era when thirty is considered old, especially for a poet, question: what's the point of it all. And here lies the second key, and it is one we have in fact found at least once before: Sonnets 71 & 72 in all but certainty have to have been composed before the end of 1594, because like Sonnet 66, they no longer make much sense thereafter.

And so the question, can these two sonnets be seen as a reflection of a wider crisis in Shakespeare's life may I believe be answered emphatically. Yes. Everything speaks to this, including the sonnets that surround them, most especially Sonnet 66. And Sonnets 73 & 74 will confirm this and shed yet more light on William Shakespeare's state of mind, and not only that, but – and this, as we shall very shortly see, is genuinely significant – they will also show us that Shakespeare himself takes his sonnets absolutely seriously: to him, they are far from worthless, they are of substance.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!