Sonnet 33: Full Many a Glorious Morning Have I Seen

|

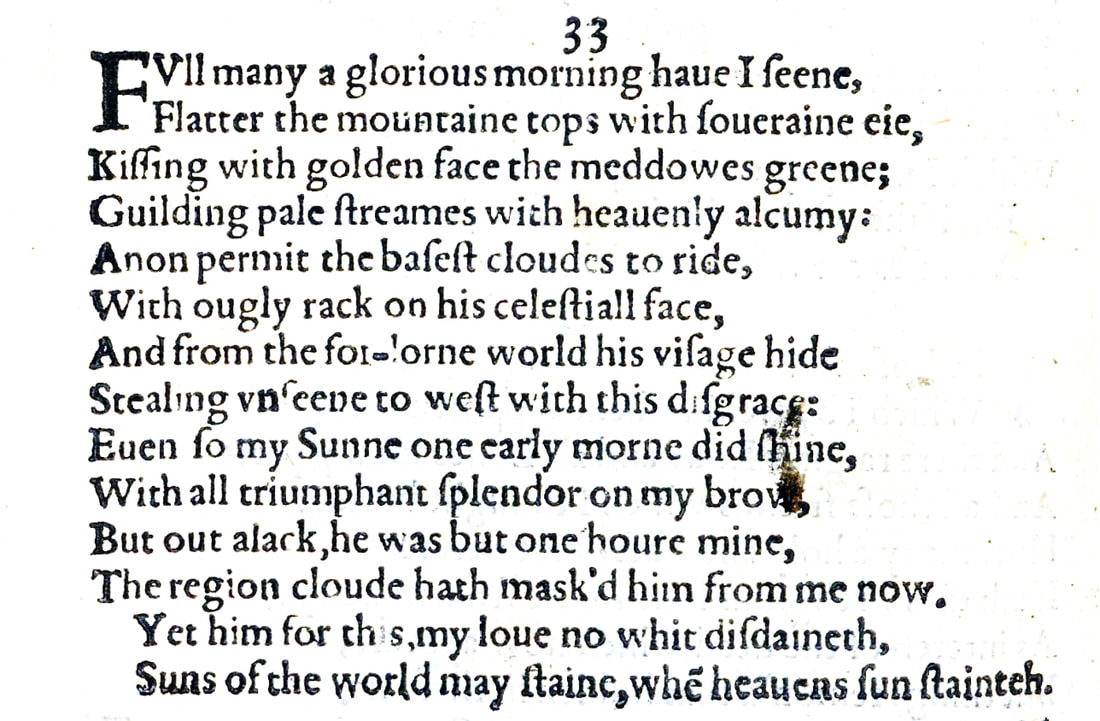

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye, Kissing with golden face the meadows green, Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy, Anon permit the basest clouds to ride With ugly rack on his celestial face, And from the forlorn world his visage hide, Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace. Even so my sun one early morn did shine With all triumphant splendour on my brow, But out, alack, he was but one hour mine: The region cloud hath masked him from me now. Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth: Suns of the world may stain when heaven's sun staineth. |

|

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye |

I have seen a great many mornings when the sun's rays caress the mountain tops...

The 'sovereign eye', like 'the eye of heaven' in Sonnet 18, is the sun, with which the morning 'flatters' the mountain tops. 'Flatter' does have the same meaning in Shakespeare as it does for us, and because the sovereign – the king or the queen – is the highest individual there is in a monarchy, everyone they look at benignly is in a sense being flattered. So when the morning looks on the world with the sun, its heavenly eye, it does flatter the world, by making it appear and feel better than it really is or certainly than it would without this light and warmth coming to it. Here though, as elsewhere in Shakespeare, the word also means to stroke or to caress, as the sun metaphorically does the peaks with its rays in the early morning when it first rises. 'Full many' meanwhile, has the same meaning as what we would call 'a great many' or simply 'very many'. |

|

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

|

...and with its golden face kiss the green meadows...

The idyll of the sun gently greeting the pastoral landscape continues: the 'golden face' similarly echoes Sonnet 18, where the personified sun had a 'gold complexion'. |

|

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy,

|

...and with its heavenly alchemy turn pale streams into gold: the light of the sun lends the water of the streams, which in the twilight looked silvery pale, a golden shimmer and sheen.

Alchemy is the mediaeval practice of trying to turn base metals into gold and in the era before Newton and what we would consider modern science occupies a mystical place between magic, experimentation, and early chemistry. Here it is heavenly because the sun is of the heaven and therefore possesses its own, quasi-divine, sovereign power to achieve this wonder of the morning. Note that 'heavenly' is here pronounced with two syllables: hea'nly, and 'alchemy' strictly speaking should be pronounced to rhyme with eye, although mostly this is in contemporary practice ignored. |

|

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face |

And soon after this has happened, I have then seen the same morning allow a line of ugly clouds of the lowest order to ride on his heavenly face.

The weather is turning. After the glorious sunshine of the early hours of the morning, an unseemly procession of clouds comes along, and the morning, which just a short while ago was flattering the world with his sovereign eye, is now allowing that same face – the sun – to be besmeared by clouds. The use of the word 'basest' is not coincidental: it contrasts the status of these clouds as low and vulgar compared to the exalted sovereignty of the sun, and it also references the 'base metals' that the alchemist would aim to turn into gold. |

|

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace. |

And these clouds thus hide the face of the sun from the abandoned, lost world, as it steals away to the west where it sets, carrying this disgrace with it.

'Disgrace' is a particularly strong term which carries with it moral connotations, and these will shortly become clear. If Shakespeare were only talking about the weather here, then it would be startling to find him so judgmental about a purely natural phenomenon, but: |

|

Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendour on my brow, |

In just the same way, my sun – which we can guess and learn in a moment is my young lover – one fine morning did shine for me...

The young man is here compared to the sun who, in his "triumphant splendour," meaning his glorious, bright shining beauty and apparel, turns my day into a golden wonder. And this is a third echo of when it all started so joyously with Sonnet 18, where I asked him: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" There I told the young man that he was "more lovely, and more temperate," here, not so much... Note that 'even' is pronounced with one syllabe: e'en. |

|

But out, alack, he was but one hour mine:

The region cloud hath masked him from me now. |

But – alas! – this glorious sunshine lasted only a short while and the clouds of the upper regions of the sky have now obscured him from my view.

Just as with the sun in the sky when it is covered by clouds, and the day turns from warm, bright and happy to grey, cold and drab, so this sun of a man that briefly shone on me is now hidden behind ugly clouds. The 'out, alack' is not as tricky as we might feel inclined to make it: it's simply an expression of woe, just like alas! Debates happen over how to punctuate this, and a good argument can be made for leaving the whole expression 'but out alack' stand as one, the way the Quarto Edition does. |

|

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth:

Suns of the world may stain when heaven's sun staineth. |

And yet, the love that I bear for him is in no way diminished, I do not like or esteem him any less for this, because if the sun in the sky can be blemished, as it so often is, without us thinking less of it, then so can the suns of the world: great people like my young lover.

The comparison of the young man to the sun is drawn to a logical conclusion: the sun is the sun and always will be: it is the source of all our energy and it commands the sky. The fact that now and then it is obscured from us and seems tainted by some mean clouds does not take away from its absolute sovereignty. And the same applies to my young man: he is, in a sense, beyond reproach, if nothing else for his unimpeachable status. |

With Sonnet 33 a new phase begins in the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man. The storm clouds that gather in this poem are a direct and intentional metaphor for the turbulence the two face, as the young man has clearly gone and done something to upset his loving poet. What exactly this is, the sonnet doesn't tell us, but it is obvious that Shakespeare is hurt and disappointed, whilst trying to rationalise the young man's behaviour in a way that makes some sort of sense to him.

This sonnet is striking and most revealing for a whole raft of reasons. The first thing that catches our attention and that can hardly be a coincidence is the way it references – echoes even – Sonnet 18. Sonnet 18 may or may not mark the beginning of the 'relationship proper', so to speak, between Shakespeare and the young man, but it certainly stands at the point in the published sequence where the relationship shifts from being mostly transactional and almost exclusively concerned with the young man's procreation, to one of undisguised adoration. The fact that this sonnet in at least three instances that we noted directly picks up on themes that strongly feature there does not prove anything, but it strongly suggests that our contention is right that all these sonnets so far are addressed to the same young man and that at this juncture, where the glorious warmth and sunshine of a metaphorical summer day is being ruined by ugly clouds, I, the poet, either consciously or subconsciously hark back to when everything seemed like it could be or become all but perfect.

The second aspect that stands out here is the positioning of the young man in relation to William Shakespeare. We have, in our journey thus far, observed that the young man whom all of these sonnets appear to be about must be of a high social status. Everything we have seen and heard suggests as much, nothing has come up that allows us to think otherwise. Sonnet 33 strongly supports this contention. Of course, it is entirely possible for a person who is in love to liken their lover to a sun: "You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are grey," the charming ditty goes, and we are hardly pushed to think of this 'sunshine' as necessarily a person of high social status.

But William Shakespeare – unlike Oliver Hood who is believed to have written that song in the 1930s – was composing his verses in the 1590s at a time when English society was wholly defined by class and where being a member of the aristocracy carried with it untold privileges as much as quite extraordinarily far-reaching obligations. Which is why Shakespeare linking this sun in his life to sovereignty is so significant: the sun of the sky is described as the 'sovereign eye' and this exalted state is being disgraced – not just tarnished or simply obscured, but morally devalued – by the clouds that come in front of it. The young man is described as the sun who appears in 'triumphant splendour' and then similarly is masked by metaphorical clouds. And while we don't know who this man is for certain, we do know that soon Shakespeare will address him as "lascivious grace," and 'Your Grace' – today used at the level of a Duchess or a Duke – in Shakespeare's day is a form of address that could be appropriate also for an Earl. So the suggestion made by the poem that this sun has, in the eyes of the poet, allowed himself to be thus 'dis-graced', is far-reaching and profound.

That these 'clouds' therefore are no trivial matter will become crystal clear in the ensuing sonnets, but what happens next in this sonnet is almost startling and amounts to the third element that immediately strikes us as noteworthy:

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth:

Suns of the world may stain when heaven's sun staineth.

Shakespeare does the poetic equivalent of a handbrake turn. This poem could have gone all manner of ways: a plea for the young man to make fair weather return, a throwing in of the towel in despair, a moral finding on the fickleness of love... What he actually does is absolve the young man of any wrongdoing, not by saying he didn't do it, but by saying: that's his prerogative. After all, he is the sun in my life: he is up there and I am down here. He is sovereign; who am I to lament the clouds: he is and always will be the sun.

This does several things all at once: it puts the poet in place, it relativises the accusation such as it is, it amounts to more or less the equivalent of someone saying to their partner: I realise you cannot commit. To invoke another fine tune of the twentieth century: it's a bit like Shakespeare saying to his young man: "You don't have to say you love me, just be close at hand / You don't have to stay forever, I will understand: / Believe me, believe me, I can't help but love you / But believe me, I will never tie you down..." as Dusty Springfield so heartrendingly sang in the lyric written for her by Vicki Wickham and Simon Napier-Bell.

Whether we can take Shakespeare entirely at face value and believe he absolutely means what he is saying, that is another question, and not one that this sonnet can answer. Luckily, though, it doesn't have to.

Because although Sonnet 33 can absolutely stand on its own and does not in that sense form an inseparable pair as some others have done, it is strongly tied into the sonnet that immediately follows, Sonnet 34, and that in turn directly leads to the next one, Sonnet 35. The three of them could therefore be seen as the first 'triptych' in the series that thematically and sequentially link into each other almost, but not quite, to the point where they could be seen as one unit. There then follows a short sequence which talks about several other things, but mostly the young man's great worth, before, with Sonnets 40 and 41, we get the clear explanation of what has actually happened. It therefore makes sense, rather than to speculate about what brings on all this bad weather, to simply take it one step at a time and see how this all unfolds. It unfolds in two dramatic waves and results in a – even by our standards – astoundingly frank and exceptionally open-minded assessment of an effectively post-modern constellation of the kind you might see discussed on any contemporary reality TV show...

This sonnet is striking and most revealing for a whole raft of reasons. The first thing that catches our attention and that can hardly be a coincidence is the way it references – echoes even – Sonnet 18. Sonnet 18 may or may not mark the beginning of the 'relationship proper', so to speak, between Shakespeare and the young man, but it certainly stands at the point in the published sequence where the relationship shifts from being mostly transactional and almost exclusively concerned with the young man's procreation, to one of undisguised adoration. The fact that this sonnet in at least three instances that we noted directly picks up on themes that strongly feature there does not prove anything, but it strongly suggests that our contention is right that all these sonnets so far are addressed to the same young man and that at this juncture, where the glorious warmth and sunshine of a metaphorical summer day is being ruined by ugly clouds, I, the poet, either consciously or subconsciously hark back to when everything seemed like it could be or become all but perfect.

The second aspect that stands out here is the positioning of the young man in relation to William Shakespeare. We have, in our journey thus far, observed that the young man whom all of these sonnets appear to be about must be of a high social status. Everything we have seen and heard suggests as much, nothing has come up that allows us to think otherwise. Sonnet 33 strongly supports this contention. Of course, it is entirely possible for a person who is in love to liken their lover to a sun: "You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are grey," the charming ditty goes, and we are hardly pushed to think of this 'sunshine' as necessarily a person of high social status.

But William Shakespeare – unlike Oliver Hood who is believed to have written that song in the 1930s – was composing his verses in the 1590s at a time when English society was wholly defined by class and where being a member of the aristocracy carried with it untold privileges as much as quite extraordinarily far-reaching obligations. Which is why Shakespeare linking this sun in his life to sovereignty is so significant: the sun of the sky is described as the 'sovereign eye' and this exalted state is being disgraced – not just tarnished or simply obscured, but morally devalued – by the clouds that come in front of it. The young man is described as the sun who appears in 'triumphant splendour' and then similarly is masked by metaphorical clouds. And while we don't know who this man is for certain, we do know that soon Shakespeare will address him as "lascivious grace," and 'Your Grace' – today used at the level of a Duchess or a Duke – in Shakespeare's day is a form of address that could be appropriate also for an Earl. So the suggestion made by the poem that this sun has, in the eyes of the poet, allowed himself to be thus 'dis-graced', is far-reaching and profound.

That these 'clouds' therefore are no trivial matter will become crystal clear in the ensuing sonnets, but what happens next in this sonnet is almost startling and amounts to the third element that immediately strikes us as noteworthy:

Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth:

Suns of the world may stain when heaven's sun staineth.

Shakespeare does the poetic equivalent of a handbrake turn. This poem could have gone all manner of ways: a plea for the young man to make fair weather return, a throwing in of the towel in despair, a moral finding on the fickleness of love... What he actually does is absolve the young man of any wrongdoing, not by saying he didn't do it, but by saying: that's his prerogative. After all, he is the sun in my life: he is up there and I am down here. He is sovereign; who am I to lament the clouds: he is and always will be the sun.

This does several things all at once: it puts the poet in place, it relativises the accusation such as it is, it amounts to more or less the equivalent of someone saying to their partner: I realise you cannot commit. To invoke another fine tune of the twentieth century: it's a bit like Shakespeare saying to his young man: "You don't have to say you love me, just be close at hand / You don't have to stay forever, I will understand: / Believe me, believe me, I can't help but love you / But believe me, I will never tie you down..." as Dusty Springfield so heartrendingly sang in the lyric written for her by Vicki Wickham and Simon Napier-Bell.

Whether we can take Shakespeare entirely at face value and believe he absolutely means what he is saying, that is another question, and not one that this sonnet can answer. Luckily, though, it doesn't have to.

Because although Sonnet 33 can absolutely stand on its own and does not in that sense form an inseparable pair as some others have done, it is strongly tied into the sonnet that immediately follows, Sonnet 34, and that in turn directly leads to the next one, Sonnet 35. The three of them could therefore be seen as the first 'triptych' in the series that thematically and sequentially link into each other almost, but not quite, to the point where they could be seen as one unit. There then follows a short sequence which talks about several other things, but mostly the young man's great worth, before, with Sonnets 40 and 41, we get the clear explanation of what has actually happened. It therefore makes sense, rather than to speculate about what brings on all this bad weather, to simply take it one step at a time and see how this all unfolds. It unfolds in two dramatic waves and results in a – even by our standards – astoundingly frank and exceptionally open-minded assessment of an effectively post-modern constellation of the kind you might see discussed on any contemporary reality TV show...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!