Sonnet 52: So Am I as the Rich, Whose Blessed Key

|

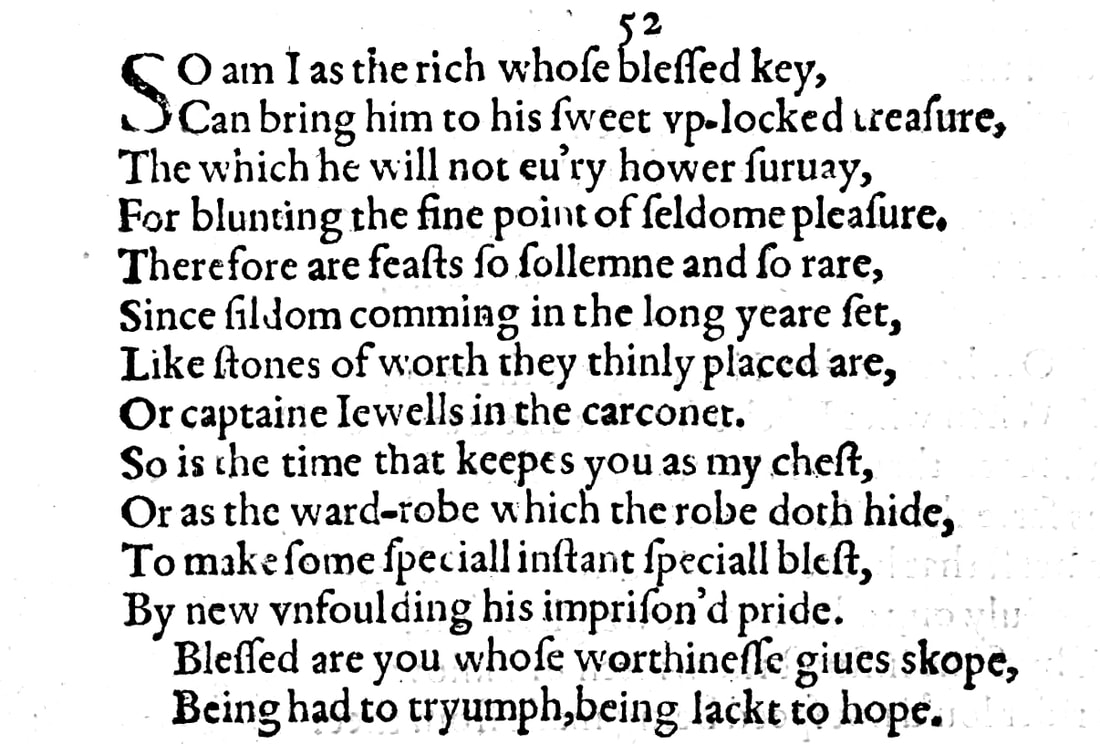

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet uplocked treasure, The which he will not every hour survey, For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure; Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare, Since seldom coming in the long year set, Like stones of worth they thinly placed are, Or captain jewels in the carcanet. So is the time that keeps you as my chest, Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide, To make some special instant special blest, By new unfolding his imprisoned pride. Blessed are you, whose worthiness gives scope, Being had, to triumph, being lacked, to hope. |

|

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet uplocked treasure, |

Thus, or now, or then, when I am back with you, in this way, I am like a rich man who has a blessed or fortune-bearing key which can bring him to the treasure that he has locked away in a safe place.

The sonnet largely appears to stand on its own, but the 'So' with which it opens does draw a link to something that has either just happened or is happening right now, and although it can only ever do so tentatively, this would suggest that a connection is being made to the previous sonnet, which talks about rushing home to the young lover. When that is done, when we are back together again, then this sense of feeling like a rich person kicks in. Also noteworthy is the reference to Sonnet 48, where I, the poet, lamented the fact that I was unable to lock up my most precious possession, the young man, except in my heart where he – much to my concern – was able to come and go as he pleased. The worry of that sonnet with these lines appears to evaporate. Note that blessèd is pronounced with two, and uplockèd with three syllables in order for the lines to scan. |

|

The which he will not every hour survey,

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure. |

He, the rich man, will not survey or look at this treasure and examine it every hour, meaning all the time or all too frequently, because this would diminish the exquisite pleasure of looking at and handling it: the 'fine point of seldom pleasure', through overuse gets blunted.

|

|

Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare,

|

This is why feast days are so ceremonial and special...

'Solemn' here largely has a meaning of 'dignified' and 'formal', rather than the more contemporary sense of 'glum' or 'cheerless'. Its Latin origin solemnis literally means 'customary, celebrated at a fixed date'. (Oxford Dictionaries) |

|

Since seldom coming in the long year set

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are, Or captain jewels in the carcanet. |

...because they appear infrequently in the annual calendar, and so they are like precious stones that are thinly placed in a piece of jewellery: the best and most valuable stones – the captain jewels – are those of which there are fewest in a necklace – a carcanet – which makes them all the more valuable...

And here placèd is pronounced with two syllables. |

|

So is the time that keeps you as my chest,

|

And so the time that keeps you away from me, meaning the time that we spend apart, is like my chest or sturdy box or what today we would think of as a safe.

As in Sonnet 48 – and this is another clear reference to it – 'chest' evokes not only these meanings, but also the human chest where the heart resides and where in Sonnet 48 I thought I had locked up my lover for safekeeping, even though he was at liberty to come and go. |

|

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide,

To make some special instant special blest By new unfolding his imprisoned pride. |

Or the time that keeps you away from me is like the wardrobe which hides a robe so that when I open it again and take out this special garment, it newly unfolds the pride that it represents and embodies and that had been imprisoned in the wardrobe.

The use of the word 'pride' here is no doubt significant, and we will look at this more closely, because it of course means the splendour and rich possession which the bearer is proud to own and show off, but it also strikes a much more sexually suggestive note, and this can hardly be ignored here... |

|

Blessed are you, whose worthiness gives scope

Being had to triumph, being lacked, to hope. |

You are blessed – or even just 'bless you' – who you are of such great worth that when I have you I am allowed to feel triumphant in this possession, and when you lack because you are absent from me or I from you, I may still hold hope and look forward to the time when we are together again.

And blessèd is once more pronounced with two syllables. |

The astonishingly suggestive Sonnet 52 is the closest William Shakespeare has come so far to answering in his own words the question that has agitated readers of these sonnets for centuries: is this a physical, even sexual, relationship he is having with the young man, or could it not simply be one that is very close, maybe romantic, but nevertheless purely platonic. With its choice and precisely placed vocabulary, it relates an either already experienced or imminent reunion and thus also marks the end of the prolonged period of separation that appears to have been imposed on Shakespeare and his young lover since Sonnet 43.

Whenever we make bold statements such as 'this is a revelatory sonnet' – which I certainly argue it is – or 'William Shakespeare with this unlocks his heart for us', to paraphrase William Wordsworth once more, we have to preamble this with the caveat: we only have the words. There is no physical, documentary, evidence that clarifies anything about this relationship for us beyond conjecture and reasonable doubt, and there is extremely scant circumstantial evidence that may help us understand who the young man is and what the exact nature of their relationship. Many scholars, especially those of a generation who grew up in the mid-20th century when English society – as indeed most other Western societies – took an extremely dim view of same sex relationships have settled into an approach that either skirts around the issue of sexuality altogether or goes so far as to argue that we simply shouldn't care who this person is or how Shakespeare relates to him, that as poetry this all lives in the mind of the poet who writes for the sake of writing poetry alone in a world that is therefore abstract and removed from any real-life context.

This is an essential point to make, and so I hope you will bear with me if I elaborate on this a bit, because if we want to understand Shakespeare, we need to understand on the one hand the cultural context in which he writes and also, equally important, we need to be aware of the cultural context in which he is being read and interpreted, because with anything that we read, but particularly with a sonnet like this, which has what some might consider to be contentious content, cultural context will determine how we understand what it says.

The editions of the sonnets that people of my generation grew up with were published in the 1970s and 1980s and edited largely by scholars who had studied in the 1950s and 1960s. Homosexuality was illegal – not just frowned upon or faced with societal prejudices, but forbidden by law, in England and Wales until 1969, when it was partially legalised for men aged 21 and above, as long as any activity that could be seen as 'homosexual' happened in private. The same law was extended to Scotland in 1980 and Northern Ireland in 1982. Civil partnerships that afforded very similar but not entirely identical rights to same sex couples as marriage were introduced in 2005 and full equal marriage in 2014.

Why should any of this matter to the discussion of a Shakespearean sonnet? Because for literally centuries, but most particularly ever since the highly censorious and moralistic Victorian era and deep into the 20th century, the idea that a 'romantic friendship' between men could have a sexual component was considered greatly disturbing – people at the time used words more like 'disgusting' and 'vile' – and therefore it was also considered fundamentally, morally, 'wrong'.

Since we are on the legal and societal framework as a context, it is also worth bearing in mind and acknowledging that of course there were no 'LGBT rights' in Shakespeare's day either; in fact there was no conception of 'gay', 'lesbian', 'bisexual' or 'trans', as we understand these terms today, at all. The term 'homosexual' itself was not coined until the very late 19th century, and then in a clinical sense. So almost everything we today think and express about human sexuality is coloured entirely differently to the way Shakespeare and his contemporaries would have understood it.

Without wanting to go into too much detail on sexual practice in a podcast on poetry, Christianity looked on all sex that didn't serve procreation as sinful, and so under Henry VIII – the father of Queen Elizabeth I – parliament in England passed the Buggary Act of 1533, which made sodomy – or 'buggary' as it was referred to here, without ever defining it – punishable by death irrespective of the gender of the persons involved. Under Queen Victoria in the 1800s this law was repealed and while the death penalty for this particular 'offence', as it was still very much considered, was commuted to a life sentence of 'penal servitude' – what we otherwise know as 'hard labour' – homosexuality remained punishable by imprisonment. This was not only enforced but actively pursued right into the 1950s, with police deliberately setting 'honey traps' to identify and arrest men for seeking sexual contact with other men, even in their own homes.

And so we need to acknowledge two things:

1) At the time when Shakespeare wrote this sonnet, as a man you could be put to death for being found to have had sex with another man, but this stark reality notwithstanding, men quite openly had lovers and favourites, including King James VI of Scotland who became King James I of England at the death of Queen Elizabeth I. And so while Shakespearean society was revulsed by certain sexual acts in particular, it had a remarkably relaxed or at any rate flexible attitude to human nature, compared to English society in the 19th and 20th centuries. This does not mean that people were generally fine with men having sex with men, but the social context was complex, multi-layered, and at least partially defined by a Renaissance mentality and awareness that reconnected strongly with classical values of Greek and Roman antiquity which – unencumbered by the moral code of the Abrahamic religions – had an entirely different approach to sexual relations to the one promoted by the Christian church.

2) For at least 200, more realistically nearly 300, years, William Shakespeare's sonnets were read in a cultural context that was fundamentally and vehemently hostile to the idea of men being sexually involved with other men. As a man you could still get arrested in London in 1985 for kissing another man in the street. And so it need not surprise us that for centuries scholars and interpreters of these sonnets, written after all by the most eminent, most celebrated poet of the English language, have contorted themselves into finding ways of arguing that really these sonnets don't talk about sex at all.

The time has clearly come to change that, and Sonnet 52 gives us ample reason to do so, starting at the end:

To be had to triumph, to be lacked to hope.

Neither Colin Burrow in the Oxford University Press edition first published in 2002, nor John Kerrigan in the Penguin Classics edition first published in 1986 – both of whom I respect highly and cite repeatedly in this podcast –make any reference to the obvious and, though euphemistic, unambiguous meaning in Shakespeare of 'to be had':

Sonnet 42:

That thou hast her, it is not all my grief,

And yet it may be said I loved her dearly.

That she hath thee is of my wailing chief,

A loss in love that touches me more nearly.

Loving offenders, thus will I excuse ye:

We can really not be in any serious doubt that the young man 'having' Shakespeare's mistress and she 'having' him is a sexual encounter.

Sonnet 129, which we will come to much later in the series, talks entirely about the sexual act, and finds it – rather than the person – to be:

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait

On purpose laid to make the taker mad,

Mad in pursuit and in possession so,

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme,

A bliss in proof, and proved a very woe.

And yes, although it is the sex that is being had here, not the person, the intense word play once again anchors the terms in each other.

Sonnet 135 is almost overburdened with innuendo and starts:

Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy Will

And indeed, the Oxford Dictionaries definition 2.10 of 'to have' is simply "to have sex with." So it is hard to argue that this is not what Shakespeare means here. What kind of sex is a wholly different matter and not one that needs to concern us, there are things that may and probably should remain private, but the idea that "To be had, to triumph, to be lacked to hope" is anything other than the most artful wordsmith in the English language telling himself, his lover, and now us, that they have and have had each other in a sexual sense is surely nothing short of disingenuous.

On its own, this would be telling. But there is a build up to it:

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet uplocked treasure.

It may or may not be coincidence and therefore it may or may no be a deliberately placed clue, but it is certainly the case and therefore noteworthy that here in the first line of Sonnet 52 is the first and only time that Shakespeare uses the word 'key' in the entire collection. This is not entirely banal an observation: 'key' is a highly symbolic term – today much overused as an adjective – and so one might reasonably expect Shakespeare finding frequent use for it. He doesn't. He uses it here, and here only. Then we get the 'sweet uplocked treasure'. In the context of a rich person, the treasure is obviously their material wealth, their money and jewellery, which is here used as a metaphor for my lover who is my 'sweet treasure': a term of endearment we still use today for a lover.

The which he will not every hour survey

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure.

The layering and the build-up continue. Of all the words William Shakespeare already has at his disposal and with his gift and given propensity for making them up as he goes along to great evocative effect, he chooses 'the fine point' – which in itself may or may not have a subtly suggestive note to it – of 'seldom pleasure'. Of course, he needs a rhyme with 'treasure' and what more obvious word would offer itself than 'pleasure', but Shakespeare, when he feels like it, does not shy away from eschewing the obvious, and here the other really obvious thing is that 'pleasure' has widely understood and instantly recognisable sensory, sensual, and sexual connotations. Frequently in these sonnets, but to cite just the one example which comes as a pair, Sonnets 57 & 58, 'pleasure' is clearly and deliberately deployed to mean sexual encounters or relations, as we shall see.

The second quatrain yields no further clues, concerning itself, as it does, with the nature of religious feasts, but then he cranks up the tone another notch, as we noticed while translating these lines a little earlier:

So is the time that keeps you as my chest

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide

To make some special instant special blest

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Now, personifying the robe is not in itself unusual: we have seen this many times before and shall do so again: Shakespeare often refers to objects by the personal pronoun. Here though it results in a 'special instant' being made 'special blest' – and note the rhetorical device here of repeating the word 'special' – "by new unfolding his imprisoned pride." Granted, we can argue, and I know some people would, that a special robe for a special occasion is a symbol and therefore expression of status and thus by extension the pride the owner has in his possession, but after everything that's gone before, and knowing from the outset that the 'sweet uplocked treasure' we are talking about is a young man, we would really have to be tone deaf once more to ignore the fact that pride is by definition "a person or thing that arouses a feeling of deep pleasure or satisfaction," and so unsurprisingly also carries really rather strong sexual connotations.

Some editors have suggested that Sonnet 52 is rich in further clues and secret meanings, noting for example that its number in the series, 52, happens to equal the number of weeks in a year, and noting the strongly religious themed middle section of the poem. This may well be so, but exploring these would take us entirely into the realm of pure speculation and theory, and my declared intention with this podcast is to listen to the words and really the words only. And this much I strongly sense we can say: Sonnet 52 is a key sonnet. It does not unlock all of Shakespeare's heart for us – no one single sonnet does – but it forms a composition that comes so very close to being explicit in its expression of a physical dimension that, together with everything else we have learnt so far – the innuendo of Sonnets 15 & 16, the in itself revelatory Sonnet 31, the complex triangular constellation of Sonnet 33 intermittently onwards – and of what is yet to come, I am willing to declare my hand and say: this is, in one way or another, sex we are talking about.

In all this though, we mustn't lose track of the sheer joy and exuberance this poem conveys. From the dull drudgery and deprivation of slowly traipsing through the English countryside, we find ourselves in a wealth of sensory riches that celebrates at long last being together again. And if Sonnet 52 gives us a notion of a close physical, indeed sexual reunion, then Sonnet 53 gloriously supports this, reminding us, as it does in tone and wonder, of a blissful morning after...

Whenever we make bold statements such as 'this is a revelatory sonnet' – which I certainly argue it is – or 'William Shakespeare with this unlocks his heart for us', to paraphrase William Wordsworth once more, we have to preamble this with the caveat: we only have the words. There is no physical, documentary, evidence that clarifies anything about this relationship for us beyond conjecture and reasonable doubt, and there is extremely scant circumstantial evidence that may help us understand who the young man is and what the exact nature of their relationship. Many scholars, especially those of a generation who grew up in the mid-20th century when English society – as indeed most other Western societies – took an extremely dim view of same sex relationships have settled into an approach that either skirts around the issue of sexuality altogether or goes so far as to argue that we simply shouldn't care who this person is or how Shakespeare relates to him, that as poetry this all lives in the mind of the poet who writes for the sake of writing poetry alone in a world that is therefore abstract and removed from any real-life context.

This is an essential point to make, and so I hope you will bear with me if I elaborate on this a bit, because if we want to understand Shakespeare, we need to understand on the one hand the cultural context in which he writes and also, equally important, we need to be aware of the cultural context in which he is being read and interpreted, because with anything that we read, but particularly with a sonnet like this, which has what some might consider to be contentious content, cultural context will determine how we understand what it says.

The editions of the sonnets that people of my generation grew up with were published in the 1970s and 1980s and edited largely by scholars who had studied in the 1950s and 1960s. Homosexuality was illegal – not just frowned upon or faced with societal prejudices, but forbidden by law, in England and Wales until 1969, when it was partially legalised for men aged 21 and above, as long as any activity that could be seen as 'homosexual' happened in private. The same law was extended to Scotland in 1980 and Northern Ireland in 1982. Civil partnerships that afforded very similar but not entirely identical rights to same sex couples as marriage were introduced in 2005 and full equal marriage in 2014.

Why should any of this matter to the discussion of a Shakespearean sonnet? Because for literally centuries, but most particularly ever since the highly censorious and moralistic Victorian era and deep into the 20th century, the idea that a 'romantic friendship' between men could have a sexual component was considered greatly disturbing – people at the time used words more like 'disgusting' and 'vile' – and therefore it was also considered fundamentally, morally, 'wrong'.

Since we are on the legal and societal framework as a context, it is also worth bearing in mind and acknowledging that of course there were no 'LGBT rights' in Shakespeare's day either; in fact there was no conception of 'gay', 'lesbian', 'bisexual' or 'trans', as we understand these terms today, at all. The term 'homosexual' itself was not coined until the very late 19th century, and then in a clinical sense. So almost everything we today think and express about human sexuality is coloured entirely differently to the way Shakespeare and his contemporaries would have understood it.

Without wanting to go into too much detail on sexual practice in a podcast on poetry, Christianity looked on all sex that didn't serve procreation as sinful, and so under Henry VIII – the father of Queen Elizabeth I – parliament in England passed the Buggary Act of 1533, which made sodomy – or 'buggary' as it was referred to here, without ever defining it – punishable by death irrespective of the gender of the persons involved. Under Queen Victoria in the 1800s this law was repealed and while the death penalty for this particular 'offence', as it was still very much considered, was commuted to a life sentence of 'penal servitude' – what we otherwise know as 'hard labour' – homosexuality remained punishable by imprisonment. This was not only enforced but actively pursued right into the 1950s, with police deliberately setting 'honey traps' to identify and arrest men for seeking sexual contact with other men, even in their own homes.

And so we need to acknowledge two things:

1) At the time when Shakespeare wrote this sonnet, as a man you could be put to death for being found to have had sex with another man, but this stark reality notwithstanding, men quite openly had lovers and favourites, including King James VI of Scotland who became King James I of England at the death of Queen Elizabeth I. And so while Shakespearean society was revulsed by certain sexual acts in particular, it had a remarkably relaxed or at any rate flexible attitude to human nature, compared to English society in the 19th and 20th centuries. This does not mean that people were generally fine with men having sex with men, but the social context was complex, multi-layered, and at least partially defined by a Renaissance mentality and awareness that reconnected strongly with classical values of Greek and Roman antiquity which – unencumbered by the moral code of the Abrahamic religions – had an entirely different approach to sexual relations to the one promoted by the Christian church.

2) For at least 200, more realistically nearly 300, years, William Shakespeare's sonnets were read in a cultural context that was fundamentally and vehemently hostile to the idea of men being sexually involved with other men. As a man you could still get arrested in London in 1985 for kissing another man in the street. And so it need not surprise us that for centuries scholars and interpreters of these sonnets, written after all by the most eminent, most celebrated poet of the English language, have contorted themselves into finding ways of arguing that really these sonnets don't talk about sex at all.

The time has clearly come to change that, and Sonnet 52 gives us ample reason to do so, starting at the end:

To be had to triumph, to be lacked to hope.

Neither Colin Burrow in the Oxford University Press edition first published in 2002, nor John Kerrigan in the Penguin Classics edition first published in 1986 – both of whom I respect highly and cite repeatedly in this podcast –make any reference to the obvious and, though euphemistic, unambiguous meaning in Shakespeare of 'to be had':

Sonnet 42:

That thou hast her, it is not all my grief,

And yet it may be said I loved her dearly.

That she hath thee is of my wailing chief,

A loss in love that touches me more nearly.

Loving offenders, thus will I excuse ye:

We can really not be in any serious doubt that the young man 'having' Shakespeare's mistress and she 'having' him is a sexual encounter.

Sonnet 129, which we will come to much later in the series, talks entirely about the sexual act, and finds it – rather than the person – to be:

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait

On purpose laid to make the taker mad,

Mad in pursuit and in possession so,

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme,

A bliss in proof, and proved a very woe.

And yes, although it is the sex that is being had here, not the person, the intense word play once again anchors the terms in each other.

Sonnet 135 is almost overburdened with innuendo and starts:

Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy Will

And indeed, the Oxford Dictionaries definition 2.10 of 'to have' is simply "to have sex with." So it is hard to argue that this is not what Shakespeare means here. What kind of sex is a wholly different matter and not one that needs to concern us, there are things that may and probably should remain private, but the idea that "To be had, to triumph, to be lacked to hope" is anything other than the most artful wordsmith in the English language telling himself, his lover, and now us, that they have and have had each other in a sexual sense is surely nothing short of disingenuous.

On its own, this would be telling. But there is a build up to it:

So am I as the rich, whose blessed key

Can bring him to his sweet uplocked treasure.

It may or may not be coincidence and therefore it may or may no be a deliberately placed clue, but it is certainly the case and therefore noteworthy that here in the first line of Sonnet 52 is the first and only time that Shakespeare uses the word 'key' in the entire collection. This is not entirely banal an observation: 'key' is a highly symbolic term – today much overused as an adjective – and so one might reasonably expect Shakespeare finding frequent use for it. He doesn't. He uses it here, and here only. Then we get the 'sweet uplocked treasure'. In the context of a rich person, the treasure is obviously their material wealth, their money and jewellery, which is here used as a metaphor for my lover who is my 'sweet treasure': a term of endearment we still use today for a lover.

The which he will not every hour survey

For blunting the fine point of seldom pleasure.

The layering and the build-up continue. Of all the words William Shakespeare already has at his disposal and with his gift and given propensity for making them up as he goes along to great evocative effect, he chooses 'the fine point' – which in itself may or may not have a subtly suggestive note to it – of 'seldom pleasure'. Of course, he needs a rhyme with 'treasure' and what more obvious word would offer itself than 'pleasure', but Shakespeare, when he feels like it, does not shy away from eschewing the obvious, and here the other really obvious thing is that 'pleasure' has widely understood and instantly recognisable sensory, sensual, and sexual connotations. Frequently in these sonnets, but to cite just the one example which comes as a pair, Sonnets 57 & 58, 'pleasure' is clearly and deliberately deployed to mean sexual encounters or relations, as we shall see.

The second quatrain yields no further clues, concerning itself, as it does, with the nature of religious feasts, but then he cranks up the tone another notch, as we noticed while translating these lines a little earlier:

So is the time that keeps you as my chest

Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide

To make some special instant special blest

By new unfolding his imprisoned pride.

Now, personifying the robe is not in itself unusual: we have seen this many times before and shall do so again: Shakespeare often refers to objects by the personal pronoun. Here though it results in a 'special instant' being made 'special blest' – and note the rhetorical device here of repeating the word 'special' – "by new unfolding his imprisoned pride." Granted, we can argue, and I know some people would, that a special robe for a special occasion is a symbol and therefore expression of status and thus by extension the pride the owner has in his possession, but after everything that's gone before, and knowing from the outset that the 'sweet uplocked treasure' we are talking about is a young man, we would really have to be tone deaf once more to ignore the fact that pride is by definition "a person or thing that arouses a feeling of deep pleasure or satisfaction," and so unsurprisingly also carries really rather strong sexual connotations.

Some editors have suggested that Sonnet 52 is rich in further clues and secret meanings, noting for example that its number in the series, 52, happens to equal the number of weeks in a year, and noting the strongly religious themed middle section of the poem. This may well be so, but exploring these would take us entirely into the realm of pure speculation and theory, and my declared intention with this podcast is to listen to the words and really the words only. And this much I strongly sense we can say: Sonnet 52 is a key sonnet. It does not unlock all of Shakespeare's heart for us – no one single sonnet does – but it forms a composition that comes so very close to being explicit in its expression of a physical dimension that, together with everything else we have learnt so far – the innuendo of Sonnets 15 & 16, the in itself revelatory Sonnet 31, the complex triangular constellation of Sonnet 33 intermittently onwards – and of what is yet to come, I am willing to declare my hand and say: this is, in one way or another, sex we are talking about.

In all this though, we mustn't lose track of the sheer joy and exuberance this poem conveys. From the dull drudgery and deprivation of slowly traipsing through the English countryside, we find ourselves in a wealth of sensory riches that celebrates at long last being together again. And if Sonnet 52 gives us a notion of a close physical, indeed sexual reunion, then Sonnet 53 gloriously supports this, reminding us, as it does in tone and wonder, of a blissful morning after...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!