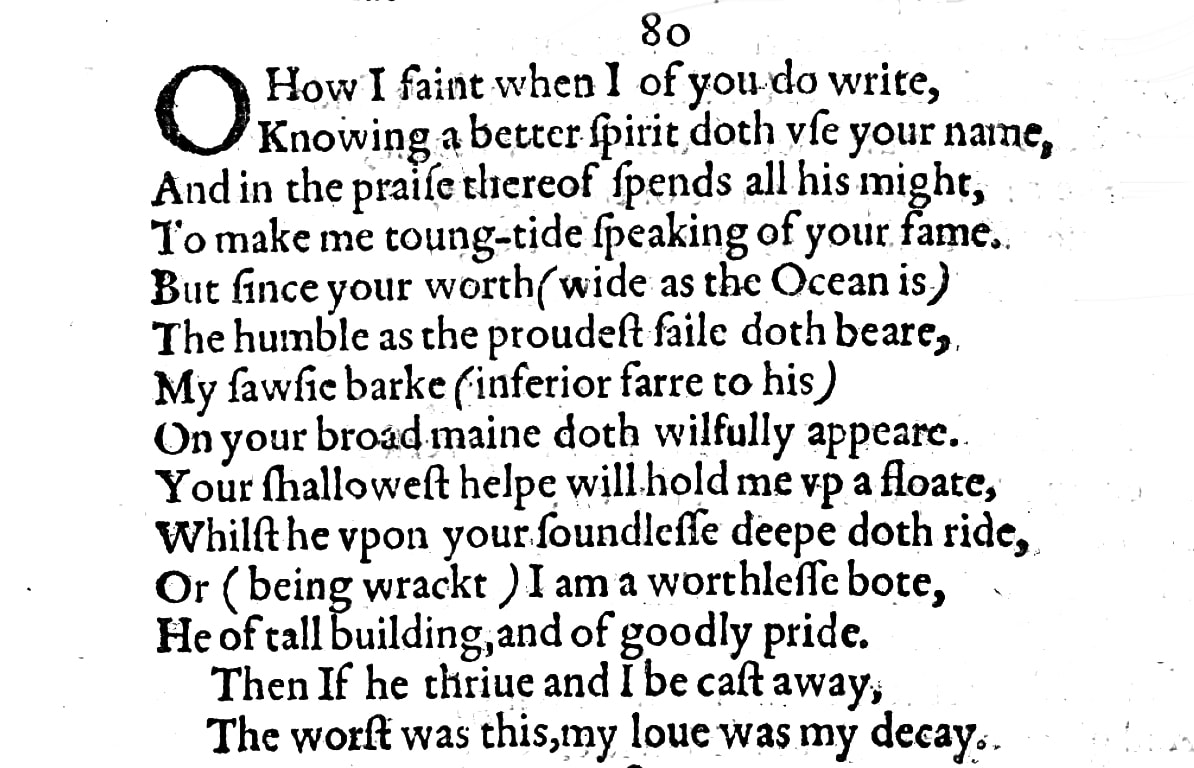

Sonnet 80: O How I Faint When I of You Do Write

|

O how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name, And in the praise thereof spends all his might To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame. But since your worth, wide as the ocean is, The humble as the proudest sail doth bear, My saucy bark, inferior far to his, On your broad main doth wilfully appear. Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat, Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride, Or, being wrecked, I am a worthless boat, He of tall building and of goodly pride. Then if he thrive and I be cast away, The worst was this, my love was my decay. |

|

O how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name, |

O how I grow weak, or feeble, how I decline, when I write of you in the knowledge that a better poet uses your name...

Even if we accept, as we must, that 'faint' in Shakespeare's day had these subtler meanings than our contemporary 'lose consciousness', the exclamatory construction of these opening lines still draws attention to itself, setting this poem up as decidedly different in tone to the two pervious ones. But the turn of phrase 'use your name' continues the transactional or utilitarian subtext of Sonnet 79, suggesting here that this other poet, this supposedly 'better spirit', not only dedicates his poetry to you or writes poetry for you, but that he does so in pursuit of or in return for some sort of payment, compensation, or favour. 'Spirit' here is pronounced with one syllable: sp'rit. |

|

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame. |

...and in praising this, your name, he spends all his powers to make me tongue-tied as I speak of your great qualities, worth, and therefore fame.

The way this sentence is phrased again draws attention to itself: we would expect the other poet to spend all his might in the pursuit of praising the young man, or speaking of the young man's fame, or doing whatever he is doing with respect directly to the young man and for his sake alone. And for all we know that may well be what this rival poet is actually doing. But Shakespeare places this in relation to himself: he makes it sound as if the rival poet's intention was to make him, Shakespeare, tongue-tied when he tries to speak of the young man's fame. This too, in a wordsmith of Shakespeare's dexterity can hardly be a mistake: he further deliberately undermines the validity of his sonnet at face value and seems to suggest yet more strongly that we need to look for, if not ulterior motives, then certainly ulterior or secondary meanings. The use of the word 'fame' here, incidentally, lends weight to our contention that the young man is a person of note. 'Fame' does not necessarily have quite the same meaning of 'being famous' as it does to us, but even if we read it more generically as 'reputation' then it still implies that the young man has a reputation in his world to start with. Also, of course, the fact alone that another poet is writing to, for, and about him makes it clear – if that were still necessary – that this young man is not a nobody. |

|

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear, |

But since your worth, which is as wide and therefore large and seemingly limitless as the ocean, is able or willing or both to bear the humble boat just as it bears the proudest ship...

In Shakespeare's day, of course, all seafaring was done with sailing vessels – the exceptions perhaps being rowing vessels – and here he sets out to compare his own modest offering to the metaphorically 'proud sail' of his rival. It is an image that he will use to similarly suggestive effect in Sonnet 86, though its suggestiveness here lies not so much in these couple of lines, but in what follows: |

|

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear. |

Shakespeare cranks up the, by now surely slightly sarcastic contrast: my presumptuous, indecorous little boat, which is far inferior to his immense ship, obstinately or stubbornly appears on the open sea of your being.

A 'bark' is simply a small boat, but the adjective 'saucy' paired with the adverb 'wilfully' lends this small boat, which stands as a metaphor for Shakespeare himself here, a deliberately and playfully disrespectful character. 'Saucy' in contemporary English means "sexually suggestive in a light-hearted and humorous way" (Oxford Languages), and although this was not so strongly the case in Elizabethan England, Shakespeare uses the word often and often in a sexual or sexually charged context. And it seems more than likely that he is at least aware of the fact that 'wilfully' puns on his name. What he also puns on – be that intentionally or not – is the bark of a dog. That's mixing metaphors, of course, but he is here referring to his writing, and if it is intentional then most likely this specific poem, as the somewhat impotent yapping of a loyal but powerless creature that is beholden to his master. 'Main' in Early Modern English simply means the open sea. |

|

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride, |

Your most modest, even, by implication, most meagre assistance will keep me afloat and going, whilst he can benefit from the unfathomable depths of your munificence.

This comparison continues to cast Shakespeare as the tiny boat that has to sail on the margins of the sheer boundless sea that is the young man's worth, staying in the shallow waters and sufficing himself with even the slightest nod of appreciation or the paltriest contribution to his upkeep, while the rival, being this amazing vessel with its majestic masts can venture far into the deep waters where the riches and therefore the returns are infinitely greater. The use of the word 'ride' once again is eye-catching, because unusual. The only other instance in the entirety of his collected works where Shakespeare uses it in a naval sense of 'riding' a boat is in Sonnet 137, where, as we shall see when we come to it, it carries very strong sexual undertones. Everywhere else in Shakespeare 'ride' is used either metaphorically, or, much more often, literally to mean riding a horse. |

|

Or, being wrecked, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building and of goodly pride. |

Or if it goes as far as me being shipwrecked, because in these shallow waters to which I am confined I run aground, or because the – possibly implied – turbulence of your unsteady and at times tempestuous sea throws me against a rock, I am then a worthless boat, whilst he – out in the open sea of your bounteous being – remains what he is: of a tall build and a proud, strong appearance.

The last time we came across 'pride' in these sonnets was in Sonnet 76, where we noted its implication in the context there of ostentation and showiness, and this very likely here is also partly intended. Before then though, in Sonnet 52, we identified strong and obvious sexual connotations with the word 'pride' as well, and having set such a subversive tone to this sonnet, we cannot entirely get away from the sense that Shakespeare here is punning and putting into our minds the idea of a strong, well-built man who is endowed with more than just an impressive upright metre... |

|

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this: my love was my decay. |

And so if it is or will be the case, that he thrives on your rich, yielding sea, and I am cast away as a shipwreck on an island of inconsequence and despair, then the worst aspect to this, the most terrible thing about it all is that it was my love, as in my love for you, or equally, it was you, my love, that caused my ruin.

The way the sentence is structured allows for a secondary reading also of: the worst that will then have happened, as in answer to the question, 'what's the worst that can happen?' will be that it was my love for you, or you my love, that caused my ruin. Considering the severity of the situation overall for Shakespeare, this latter interpretation to me sounds somewhat less likely and rather less satisfactory, but which of these two possible, similar, but subtly and still significantly different endings Shakespeare means to suggest we cannot know for certain; quite possibly he once more, as so often, knows what he is doing with words and means to suggest or offer both readings at the same time. |

With his amazingly brazen Sonnet 80, William Shakespeare metaphorically pushes the boat out in more sense than one and comes close to mocking not only his rival, but also – albeit gently – his young lover whom he insinuates being drawn to this other writer not merely by his compelling poetry, but by a prowess of an altogether more physical nature too. The poem, for all its theatricality on the one hand and its finely layered wit on the other, still ends on a pensive, even melancholy and for this quite devastating note of self-awareness.

The first striking thing to note about Sonnet 80 though, and before anything else, is that it addresses the person it is talking to as 'you'. The person it is talking to is the same person as Sonnets 78 and 79 are talking to, virtually nobody seriously doubts this, and in no reasonable universe would it make sense to assume that Shakespeare suddenly is writing to another person who also, just like the first one, happens to have allowed a rival poet into his orbit in exactly the same way. That, surely, would be a coincidence way too far.

Sonnets 78 and 79, however, are addressing their immediate primary reader or listener as 'thou'. We have, then, here proof positive that Shakespeare switches from 'thou' to 'you' within sonnets that belong together with the same person being addressed, using the two forms of address interchangeably even though they communicate a subtly but decidedly different stance of the speaker/writer in relation to the listener/reader. Shakespeare will soon switch back again: Sonnets 80 and 81 are both kept in the more formal 'you', but Sonnet 82 then reverts to 'thou' briefly, before with the remaining sonnets in the Rival Poet series, Sonnets 83, 84, 85, and 86, he then sticks with 'you'.

Why Shakespeare decides to move from 'thou' to 'you' here we don't know, he gives no direct explanation. But you may recall that on a previous occasion when he did so, in fact on the first occasion in our whole series, we ventured that he may be doing it so as to signal a certain degree of deference at a time when he was at risk of overstepping a mark. I should emphasise again here that this is speculation and we cannot know whether this is what Shakespeare intends, but when he switched from 'thou' to 'you' in the Procreation Sequence – which also, incidentally, is as good as certain to all of it be addressed to the same young man – he does so when he first calls the young man 'love'.

I will not now go over the more detailed reasons as to why this is a significant step, since that's discussed in the episode on Sonnet 13, but there too, he then briefly reverts to 'thou' with Sonnet 14, before deploying 'you' in Sonnets 15 & 16, sticking with it until Sonnet 17.

Sonnets 15 & 16, you may also recall, are the first two sonnets in which Shakespeare is, as we called it then, 'being saucy', in the sense we saw it defined above. Not quite bawdy, but almost. He there goes out on a limb and makes comments on and to the young man that lend themselves more than anything that has gone before to being understood sexually. After that and into the main body of the Fair Youth Sonnets, Shakespeare stays with 'thou', except for Sonnet 19, in which he addresses not the young man but Time, three Sonnets – 21, 25, and 33 – in which he addresses nobody in particular but talks about his love, and Sonnet 23, which he addresses directly to his young lover but without referring to him.

The next time he then uses 'you' is in Sonnet 52. And what happens there? He is being suggestive. So suggestive, in fact, that we thought at the time it was the clearest indication we had got so far that his relationship with the young man had by then acquired a sexual dimension.

And that applies here too. It doesn't – lest I give the impression it did – apply every time he uses 'you', but it applies here. Which does nothing so much as help us segue into this second, though by no means less significant, eye-catching aspect to Sonnet 80: its near-but-not-quite salaciousness, paired with a healthy lashing of sarcasm.

Shakespeare is rarely overtly sarcastic. The last time we got a strong sense of him pulling that register was in Sonnets 57 & 58, also addressed to 'you', also somewhat suggestive of the young man's sexual licentiousness. There was one milder, less convincing instance, in Sonnet 72, where we couldn't be quite sure. Here now too though it is hard to take Shakespeare entirely at face value. There are many, many of these sonnets that have a simple sincerity which doesn't change, no matter how you read them. Give Sonnet 80 a bit of thespian oomph and you are instantly in the land of comedic make-believe:

O how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame.

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride,

Or, being wrecked, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building and of goodly pride.

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this, my love was my decay.

What is especially fascinating apart from this mild mockery, though, is that it comes paired with the innuendo. This is subtle enough. If you were cautiously inclined, you would be right to counsel: none of this actually talks about sex. But then of course none would. First of all because in Shakespeare's day you just don't, directly, in plain language, speak about sex, secondly because, as we saw when discussing the previous Sonnet, 79, William Shakespeare here is in a precarious situation as it is, the last thing he needs right now is a scandalous sensation. But once or twice before has it occurred to us that when Shakespeare does something out of the ordinary to his style, he may have something out of the ordinary to say in his contents. This makes sense. If you are a poet in the world that Shakespeare inhabits, you may occasionally want or need to say something that cannot be openly expressed. How do you alert your reader or listener that they should start looking and listening between the lines? Changing the form of address, heightening the level of style, introducing humour or, here as it is, a just slightly snarky sarcasm, will certainly serve.

There's an additional element that's worthy of note. And it ties in entirely with what we have observed so far. This sonnet, much more than the previous two, introduces a note of disapproval, so as not to say accusation, of the young man himself. Sonnets 78 and 79 did not do so, they contented themselves with observing what has been happening and, in the case of Sonnet 78, asking of the young man to value Shakespeare's offering more than that of others and, in the case of Sonnet 79, advising the young man not to overestimate this rival poet for what he has to offer.

This sonnet here sails close to the wind by nearly disparaging the young man. It's not entirely obvious, but once you hear it, it's quite hard to unhear:

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride,

This, superficially, sounds like praise: your worth is wide as the ocean and this metaphorical sea is therefore capable of carrying both my humble little boat and his proud sail. But then you take into consideration that Will is being sarcastic. He doesn't really think that his saucy bark is far inferior to the other poet's grandiloquent declamations. He does not really believe that this other poet is a better spirit. And thus the praise turns faint: my saucy bark is the truth that I speak and the genuine love and devotion that I have and express for you, but your sense of self, what today we would call your ego, is so huge that you need some pompous git pouring out his full-of-himself splurges of flattery for you, probably – so this sonnet certainly implies – receiving ample compensation for it, while on top of it all being allowed ride upon your soundless deep, whatever we want to mean or mean to want by that phrase in this instance. It is not something that – to use a verb Shakespeare coins early on in the collection – happies him, and for good reason, which would explain why he closes this poem on such a sober, newly sincere, and, after all, really rather resigned note.

We are here with all this, I concede, on quite shaky ground, and there is no pun intended here. This reading of a sexual component into the relationship between now not only 'Shakey' himself and his young lover, but also between the young lover and this rival poet is conjecture. The words aren't, but our interpretation is. We will need what Shakespeare has Touchstone in As You Like It call a "better instance," indeed, as he betters this by worsening the grammar, "a more sounder instance."

And that Shakespeare himself shall provide. Not immediately. Sonnet 81 either reverts or detours to or via a more familiar, although in this case it has to be said most oddly metaphored, promise of immortality for the young man through the power of poetry, and Sonnets 82 through 85 steer well clear of anything that could be read as innuendo. But the last one of these Rival Poet Sonnets, Sonnet 86, finishes on a flourish that may just be genius, because there, bundled into an innocuous seeming couplet at the end, we find an entendre that is at least double if not triple and that serves well to explain just why our poet is so upset by the arrival on the scene of this rival poet...

The first striking thing to note about Sonnet 80 though, and before anything else, is that it addresses the person it is talking to as 'you'. The person it is talking to is the same person as Sonnets 78 and 79 are talking to, virtually nobody seriously doubts this, and in no reasonable universe would it make sense to assume that Shakespeare suddenly is writing to another person who also, just like the first one, happens to have allowed a rival poet into his orbit in exactly the same way. That, surely, would be a coincidence way too far.

Sonnets 78 and 79, however, are addressing their immediate primary reader or listener as 'thou'. We have, then, here proof positive that Shakespeare switches from 'thou' to 'you' within sonnets that belong together with the same person being addressed, using the two forms of address interchangeably even though they communicate a subtly but decidedly different stance of the speaker/writer in relation to the listener/reader. Shakespeare will soon switch back again: Sonnets 80 and 81 are both kept in the more formal 'you', but Sonnet 82 then reverts to 'thou' briefly, before with the remaining sonnets in the Rival Poet series, Sonnets 83, 84, 85, and 86, he then sticks with 'you'.

Why Shakespeare decides to move from 'thou' to 'you' here we don't know, he gives no direct explanation. But you may recall that on a previous occasion when he did so, in fact on the first occasion in our whole series, we ventured that he may be doing it so as to signal a certain degree of deference at a time when he was at risk of overstepping a mark. I should emphasise again here that this is speculation and we cannot know whether this is what Shakespeare intends, but when he switched from 'thou' to 'you' in the Procreation Sequence – which also, incidentally, is as good as certain to all of it be addressed to the same young man – he does so when he first calls the young man 'love'.

I will not now go over the more detailed reasons as to why this is a significant step, since that's discussed in the episode on Sonnet 13, but there too, he then briefly reverts to 'thou' with Sonnet 14, before deploying 'you' in Sonnets 15 & 16, sticking with it until Sonnet 17.

Sonnets 15 & 16, you may also recall, are the first two sonnets in which Shakespeare is, as we called it then, 'being saucy', in the sense we saw it defined above. Not quite bawdy, but almost. He there goes out on a limb and makes comments on and to the young man that lend themselves more than anything that has gone before to being understood sexually. After that and into the main body of the Fair Youth Sonnets, Shakespeare stays with 'thou', except for Sonnet 19, in which he addresses not the young man but Time, three Sonnets – 21, 25, and 33 – in which he addresses nobody in particular but talks about his love, and Sonnet 23, which he addresses directly to his young lover but without referring to him.

The next time he then uses 'you' is in Sonnet 52. And what happens there? He is being suggestive. So suggestive, in fact, that we thought at the time it was the clearest indication we had got so far that his relationship with the young man had by then acquired a sexual dimension.

And that applies here too. It doesn't – lest I give the impression it did – apply every time he uses 'you', but it applies here. Which does nothing so much as help us segue into this second, though by no means less significant, eye-catching aspect to Sonnet 80: its near-but-not-quite salaciousness, paired with a healthy lashing of sarcasm.

Shakespeare is rarely overtly sarcastic. The last time we got a strong sense of him pulling that register was in Sonnets 57 & 58, also addressed to 'you', also somewhat suggestive of the young man's sexual licentiousness. There was one milder, less convincing instance, in Sonnet 72, where we couldn't be quite sure. Here now too though it is hard to take Shakespeare entirely at face value. There are many, many of these sonnets that have a simple sincerity which doesn't change, no matter how you read them. Give Sonnet 80 a bit of thespian oomph and you are instantly in the land of comedic make-believe:

O how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame.

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride,

Or, being wrecked, I am a worthless boat,

He of tall building and of goodly pride.

Then if he thrive and I be cast away,

The worst was this, my love was my decay.

What is especially fascinating apart from this mild mockery, though, is that it comes paired with the innuendo. This is subtle enough. If you were cautiously inclined, you would be right to counsel: none of this actually talks about sex. But then of course none would. First of all because in Shakespeare's day you just don't, directly, in plain language, speak about sex, secondly because, as we saw when discussing the previous Sonnet, 79, William Shakespeare here is in a precarious situation as it is, the last thing he needs right now is a scandalous sensation. But once or twice before has it occurred to us that when Shakespeare does something out of the ordinary to his style, he may have something out of the ordinary to say in his contents. This makes sense. If you are a poet in the world that Shakespeare inhabits, you may occasionally want or need to say something that cannot be openly expressed. How do you alert your reader or listener that they should start looking and listening between the lines? Changing the form of address, heightening the level of style, introducing humour or, here as it is, a just slightly snarky sarcasm, will certainly serve.

There's an additional element that's worthy of note. And it ties in entirely with what we have observed so far. This sonnet, much more than the previous two, introduces a note of disapproval, so as not to say accusation, of the young man himself. Sonnets 78 and 79 did not do so, they contented themselves with observing what has been happening and, in the case of Sonnet 78, asking of the young man to value Shakespeare's offering more than that of others and, in the case of Sonnet 79, advising the young man not to overestimate this rival poet for what he has to offer.

This sonnet here sails close to the wind by nearly disparaging the young man. It's not entirely obvious, but once you hear it, it's quite hard to unhear:

But since your worth, wide as the ocean is,

The humble as the proudest sail doth bear,

My saucy bark, inferior far to his,

On your broad main doth wilfully appear.

Your shallowest help will hold me up afloat,

Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride,

This, superficially, sounds like praise: your worth is wide as the ocean and this metaphorical sea is therefore capable of carrying both my humble little boat and his proud sail. But then you take into consideration that Will is being sarcastic. He doesn't really think that his saucy bark is far inferior to the other poet's grandiloquent declamations. He does not really believe that this other poet is a better spirit. And thus the praise turns faint: my saucy bark is the truth that I speak and the genuine love and devotion that I have and express for you, but your sense of self, what today we would call your ego, is so huge that you need some pompous git pouring out his full-of-himself splurges of flattery for you, probably – so this sonnet certainly implies – receiving ample compensation for it, while on top of it all being allowed ride upon your soundless deep, whatever we want to mean or mean to want by that phrase in this instance. It is not something that – to use a verb Shakespeare coins early on in the collection – happies him, and for good reason, which would explain why he closes this poem on such a sober, newly sincere, and, after all, really rather resigned note.

We are here with all this, I concede, on quite shaky ground, and there is no pun intended here. This reading of a sexual component into the relationship between now not only 'Shakey' himself and his young lover, but also between the young lover and this rival poet is conjecture. The words aren't, but our interpretation is. We will need what Shakespeare has Touchstone in As You Like It call a "better instance," indeed, as he betters this by worsening the grammar, "a more sounder instance."

And that Shakespeare himself shall provide. Not immediately. Sonnet 81 either reverts or detours to or via a more familiar, although in this case it has to be said most oddly metaphored, promise of immortality for the young man through the power of poetry, and Sonnets 82 through 85 steer well clear of anything that could be read as innuendo. But the last one of these Rival Poet Sonnets, Sonnet 86, finishes on a flourish that may just be genius, because there, bundled into an innocuous seeming couplet at the end, we find an entendre that is at least double if not triple and that serves well to explain just why our poet is so upset by the arrival on the scene of this rival poet...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!