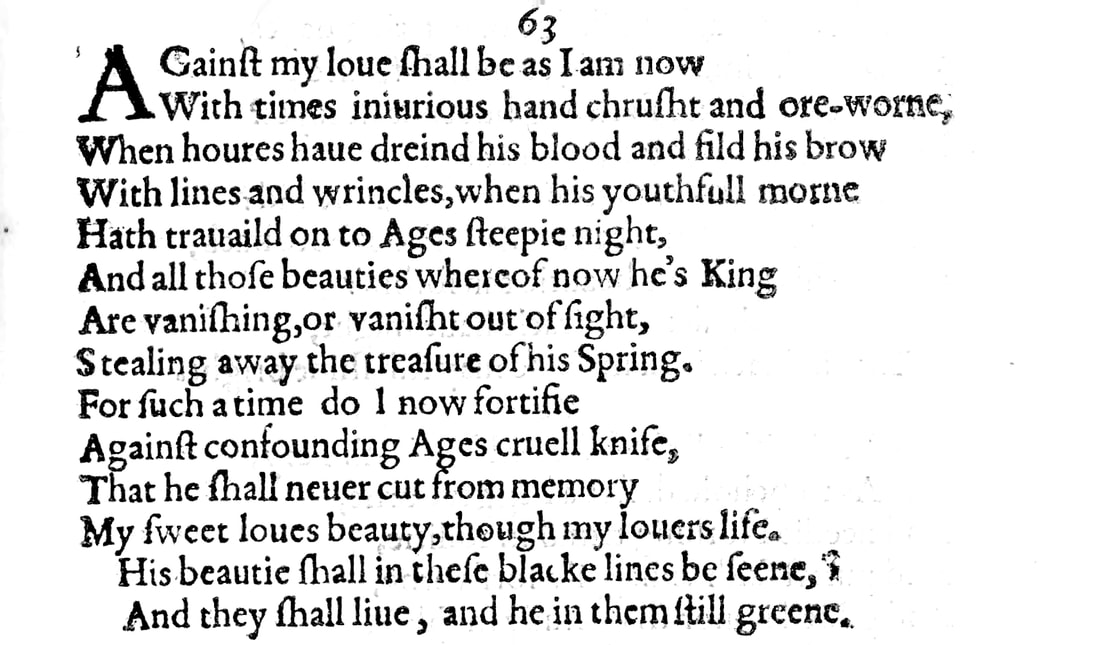

Sonnet 63: Against My Love Shall Be as I Am Now

|

Against my love shall be as I am now,

With time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn, When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn Hath travelled on to age's steepy night, And all those beauties whereof now he's king Are vanishing or vanished out of sight, Stealing away the treasure of his spring; For such a time do I now fortify Against confounding age's cruel knife, That he shall never cut from memory My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life. His beauty shall in these black lines be seen, And they shall live, and he in them still green. |

|

Against my love shall be as I am now,

With time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn, |

Against such an event or occurrence that my lover shall ever be as I am today, crushed and worn out by the injurious or damaging hand of time.

The sonnet picks up from the previous one in which Shakespeare described himself as "beated and chopped with tanned antiquity," and here now presents him as being further marked and spent or exhausted, indeed worn out, by time. |

|

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles, |

When the hours of a passing and forever destructive time have drained his blood, meaning have caused his youthful, full-blooded, and healthy appearance to go gaunt and pale, and when those same hours have filled his face with lines and wrinkles.

We have come across the use of 'brow' to mean 'face' several times before: Sonnets 2, 19, 33, and 60 all use it in this way. |

|

when his youthful morn

Hath travelled on to age's steepy night, |

When the youthful morning of his life has travelled on to the precipitous, steep decline of the night of life that comes with old age.

The use of 'steepy' here instead of 'steep' appears to be entirely in the service of prosody and to make up the syllable count, the meaning is essentially the same. |

|

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing or vanished out of sight, Stealing away the treasure of his spring; |

And when all the young man's beautiful qualities on the one hand – both external and also to some extent internal, such as youthful strength and power – but also possibly implied here, on the other hand, are the beautiful people who surround him, the dalliances, affairs, flirtations, the attractive people that cluster around an attractive, rich, and highly situated person such as this young man clearly is, when they are all beginning to disappear or have already disappeared out of sight, in the process robbing the young man of the treasure, for which read the riches, joys, and sheer wonder of his spring, his youth...

The very Shakespearean double or even triple layering of meanings here in the first two lines is especially rewarding, and even the last one of these three lines can be understood at least twofold: firstly as these youthful qualities and young people leaving the young man and with themselves also taking away the pleasures of being young, and also as these same youthful qualities and young people being the pleasures of youth and now sneaking away one by one like fair weather friends who only hang around as long as the going is good; and there lies in the very same line also the observation that of course 'those beauties whereof now he's king' – be they now qualities or people – are themselves subject to the relentless advance of time and so they are not merely leaving, in an active, deliberate choice, but actually 'vanishing', as in simply fading away into oblivion. |

|

For such a time do I here fortify

Against confounding age's cruel knife |

For the moment when such a time comes, I now here fortify myself and thus by extension also him, the young lover, against the cruel knife of a destructive age; age here going hand in hand with the passing of time, of course.

'Confound' to mean 'destroy' or 'undo' or 'wreck', also, is something we have come across before, in Sonnets 5, 8, and 60; and many times now have we noted how heartfelt and real Shakespeare's dread of the passing of time and the age that comes along with it is. |

|

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life. |

So that he, age, shall never be able to cut my sweet love's beauty from the memory of the world, although he take away his life.

The personification of age again is nothing new, but what is unusual is seeing the young man referred to twice by slightly different terms in the same line, and, as it happens, for the first time in the entire series so far as 'my lover'. We have seen Shakespeare refer to himself as the young man's 'lover', in Sonnet 32, and just before then, in Sonnet 31, Shakespeare talked about his own 'lovers gone', meaning lovers from his past. Then, in Sonnet 55 he refers to 'lovers' eyes' in which the young man, through Shakespeare's own poetry, will dwell. We have also seen Shakespeare call the young man 'sweet love', 'dear love', and indeed 'friend' before, and as we noted on at least one occasion before, we are absolutely allowed to reasonably take this 'friend' to be the same person as the 'sweet love', not least because Shakespeare uses 'my friend' in the pair 50 & 51 which is obviously addressed not just to a 'mate' but to a lover. |

|

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen

And they shall live, and he in them still green. |

His, my sweet love and lover's, beauty, shall be seen in these lines that I am writing here in black ink, and these lines shall live and he in turn will live in them forever 'green', meaning young and fresh and unaffected by the oft-cited ravages of time.

This has echoes of several previous sonnets, but most prominently Sonnet 18, of course, which promises But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou owst, Nor shall Death brag thou wandrest in his shade When in eternal lines to time thou growst: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. And for 'still' to mean 'always' – here really in the sense of 'forever' – is also not at all new, we have encountered this many times before. |

In Sonnet 63, William Shakespeare continues his reflection on his own age and now projects this as a dreaded and near-inescapable reality that will one day be visited upon his young lover, but like several sonnets that have come in the collection before, Sonnet 63 both endeavours and promises to render the young lover immune to death, age, and decay through its own everlasting power. Shakespeare thus counterpoints his horror of age and his growing despair over the unrelenting swift-footedness of time with a renewed confidence in his own poetry, and although Sonnet 63 can stand on its own, it is thematically so strongly linked to Sonnet 62 that it also serves as reliable evidence to support the contention that Sonnet 62, even though it doesn't make this explicit, is of course addressed to a young man and that this is the same young man as is referred to in Sonnet 63 and, as we have sound reason to believe. whom the majority of the sonnets so far are either addressed to or written about.

Sonnet 63 is a welcome anchor point in the series, because while it does not tell us anything profoundly new or newly profound – the substantial and substantive profundity of this sonnet has already been established with previous ones – it spells out confirmation of several observations we have made before, some of which have been called into question by scholars on occasion.

Firstly and uncontroversially, the sonnet reiterates what Sonnet 60 and 62 most recently made plain: Shakespeare frets about age. More than frets, he feels existentially threatened by it and he is entirely conscious or, as we have put it previously, acutely aware of the age difference between himself and his young lover. If this is the first time you are listening to this podcast, allow me to please refer you to the episodes covering Sonnets 60 and 62, and also earlier in the series, Sonnets 22, 32, and 37.

Secondly, and on its own no more sensational, it refers to the young lover's beauty and the 'beauties whereof now he's king' and to his own, the young lover's, youth.

Thirdly, it spells out that the person we are talking about is indeed a young man. This, though by now unspectacular, is nonetheless helpful because it confers upon us licence to continue to think of the object of William Shakespeare's affections as a beautiful young man: by definition, a fair youth. As you will know if you've been listening to this podcast and as you will have heard quite forcefully put forward by Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells in our conversation about the order of the sonnets, there are scholars who find the labels that have attached themselves to the principal characters who feature in these sonnets, namely The Fair Youth and The Dark Lady, unwarranted and seek to move away from reading the sonnets as in their majority referring themselves either directly or indirectly to them. This desire is understandable at least in so far as these labels are sometimes applied too broadly, too casually, and too categorically. That said, Sonnet 63 clearly, plainly, and quite categorically is about a beautiful young man who fits our profile of a character we have been getting to know for a bit now and whom we have, in line with convention, been thinking of as, and on occasion even calling, The Fair Youth.

Fourthly, the sonnet either reiterates and thus references or possibly recycles pronouncements made elsewhere about the capacity of poetry to immortalise this fair youth. As early as Sonnet 18 we were able to say that Shakespeare in this way creates something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, because while we can't know for certain who the young man is, we can form an idea of him and we can get to know him to quite some extent through the sonnets Shakespeare writes to, for, and about him.

The extent to which we can get to know the young man is, fifthly, widened by this sonnet. Again not in a horizon-shifting manner, but subtly and such that it reassures rather than revolutionises our understanding of this character: if we read the three self-contained lines of the second quatrain

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring

one-dimensionally, nothing much happens. Any good looking young person can and will through age lose their beauty. But Shakespeare, as so often, does not invite us to read the line one-dimensionally. He could have done so, had he wanted to. He could easily have written:

And all that beauty whereof now he's king

Is vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring

And even if he had taken umbrage, as he might, at weakening his middle line here by starting it with the less than satisfactory 'Is', he would surely have found a way of composing the sentence such that it was clear he is talking about the young man's well-noted beauty and nothing else. He doesn't. He puts the beauties into plural and in doing so invites us to read multiple meanings, which we discussed a moment ago. This makes a big difference. It not only allows but encourages us to think of those beauties also as people, as an entourage of friends, 'followers', love interests of any gender, whom the young man is 'sovereign' to, if nothing else in as much as he commands their attention. This, as previous sonnets have done, pitches him in a social strata that makes such a role possible. The stable boy or the footman, or the boy actor playing the girls in the plays, they may each in their own way be 'king' of their beauty while it lasts, but, with the exception perhaps of the boy actor who may already have his own following, they are really unlikely to be surrounded by bubbles of boys or gaggles of girls or by anyone or anything else resembling a coterie or an entourage in the way a young nobleman would be, most particularly a young nobleman who is incredibly rich, as we continue to think we have reason to believe he is.

We are here, this has to be emphasised, deep in the realm of textual interpretation, true, but it is far from fanciful, because it is entirely congruent. If what we were gleaning from our reading these lines in this way were far-fetched, unlikely, radical in its departure, then we would have to be exceptionally cautious in our pursuit of it. But what this reading yields is exactly what we have been led to expect from what we have read before. And so in this respect, too, the sonnet solidifies rather than softens our ground.

Sixthly, by calling the young man 'my sweet love' and 'my lover' in quite literally one breath, the sonnet validates our decision here taken with this podcast to not adhere to a conventional classical terminology that would tempt one to refer to William Shakespeare, being the 'older' man, as the 'lover' and to the young man as the 'beloved'. Doing so is in any case fairly rare these days and in tone old-fashioned, but you will find editors who resort to this not uninformed but, as it must be, because we have no insight into the physical aspects of their relationship, presumptuous and therefore simplistic shorthand.

And seventhly the sonnet serves as a stable bridge between Sonnet 62 and Sonnet 64, linking them thematically as much as in mood and tone, as we shall see very shortly...

Sonnet 63 is a welcome anchor point in the series, because while it does not tell us anything profoundly new or newly profound – the substantial and substantive profundity of this sonnet has already been established with previous ones – it spells out confirmation of several observations we have made before, some of which have been called into question by scholars on occasion.

Firstly and uncontroversially, the sonnet reiterates what Sonnet 60 and 62 most recently made plain: Shakespeare frets about age. More than frets, he feels existentially threatened by it and he is entirely conscious or, as we have put it previously, acutely aware of the age difference between himself and his young lover. If this is the first time you are listening to this podcast, allow me to please refer you to the episodes covering Sonnets 60 and 62, and also earlier in the series, Sonnets 22, 32, and 37.

Secondly, and on its own no more sensational, it refers to the young lover's beauty and the 'beauties whereof now he's king' and to his own, the young lover's, youth.

Thirdly, it spells out that the person we are talking about is indeed a young man. This, though by now unspectacular, is nonetheless helpful because it confers upon us licence to continue to think of the object of William Shakespeare's affections as a beautiful young man: by definition, a fair youth. As you will know if you've been listening to this podcast and as you will have heard quite forcefully put forward by Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells in our conversation about the order of the sonnets, there are scholars who find the labels that have attached themselves to the principal characters who feature in these sonnets, namely The Fair Youth and The Dark Lady, unwarranted and seek to move away from reading the sonnets as in their majority referring themselves either directly or indirectly to them. This desire is understandable at least in so far as these labels are sometimes applied too broadly, too casually, and too categorically. That said, Sonnet 63 clearly, plainly, and quite categorically is about a beautiful young man who fits our profile of a character we have been getting to know for a bit now and whom we have, in line with convention, been thinking of as, and on occasion even calling, The Fair Youth.

Fourthly, the sonnet either reiterates and thus references or possibly recycles pronouncements made elsewhere about the capacity of poetry to immortalise this fair youth. As early as Sonnet 18 we were able to say that Shakespeare in this way creates something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, because while we can't know for certain who the young man is, we can form an idea of him and we can get to know him to quite some extent through the sonnets Shakespeare writes to, for, and about him.

The extent to which we can get to know the young man is, fifthly, widened by this sonnet. Again not in a horizon-shifting manner, but subtly and such that it reassures rather than revolutionises our understanding of this character: if we read the three self-contained lines of the second quatrain

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring

one-dimensionally, nothing much happens. Any good looking young person can and will through age lose their beauty. But Shakespeare, as so often, does not invite us to read the line one-dimensionally. He could have done so, had he wanted to. He could easily have written:

And all that beauty whereof now he's king

Is vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring

And even if he had taken umbrage, as he might, at weakening his middle line here by starting it with the less than satisfactory 'Is', he would surely have found a way of composing the sentence such that it was clear he is talking about the young man's well-noted beauty and nothing else. He doesn't. He puts the beauties into plural and in doing so invites us to read multiple meanings, which we discussed a moment ago. This makes a big difference. It not only allows but encourages us to think of those beauties also as people, as an entourage of friends, 'followers', love interests of any gender, whom the young man is 'sovereign' to, if nothing else in as much as he commands their attention. This, as previous sonnets have done, pitches him in a social strata that makes such a role possible. The stable boy or the footman, or the boy actor playing the girls in the plays, they may each in their own way be 'king' of their beauty while it lasts, but, with the exception perhaps of the boy actor who may already have his own following, they are really unlikely to be surrounded by bubbles of boys or gaggles of girls or by anyone or anything else resembling a coterie or an entourage in the way a young nobleman would be, most particularly a young nobleman who is incredibly rich, as we continue to think we have reason to believe he is.

We are here, this has to be emphasised, deep in the realm of textual interpretation, true, but it is far from fanciful, because it is entirely congruent. If what we were gleaning from our reading these lines in this way were far-fetched, unlikely, radical in its departure, then we would have to be exceptionally cautious in our pursuit of it. But what this reading yields is exactly what we have been led to expect from what we have read before. And so in this respect, too, the sonnet solidifies rather than softens our ground.

Sixthly, by calling the young man 'my sweet love' and 'my lover' in quite literally one breath, the sonnet validates our decision here taken with this podcast to not adhere to a conventional classical terminology that would tempt one to refer to William Shakespeare, being the 'older' man, as the 'lover' and to the young man as the 'beloved'. Doing so is in any case fairly rare these days and in tone old-fashioned, but you will find editors who resort to this not uninformed but, as it must be, because we have no insight into the physical aspects of their relationship, presumptuous and therefore simplistic shorthand.

And seventhly the sonnet serves as a stable bridge between Sonnet 62 and Sonnet 64, linking them thematically as much as in mood and tone, as we shall see very shortly...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!