Sonnet 35: No More Be Grieved at That Which Thou Hast Done

|

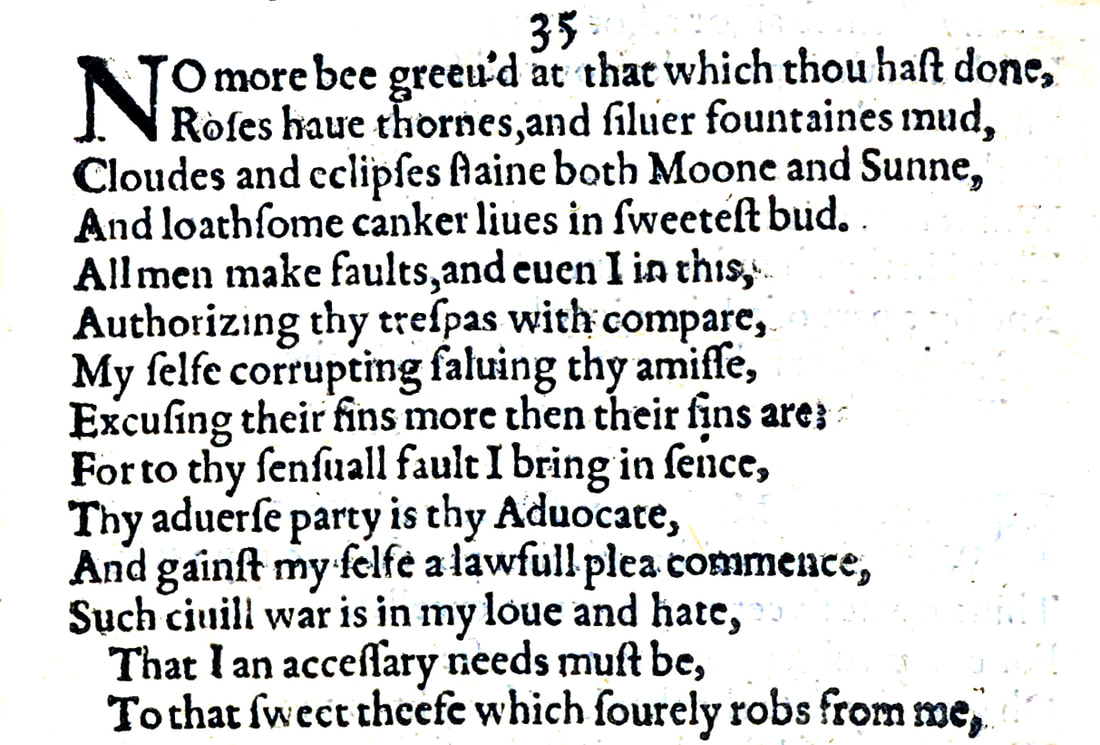

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns and silver fountains mud; Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun, And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud. All men make faults, and even I in this, Authorising thy trespass with compare, Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss, Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are; For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense, Thy adverse party is thy advocate, And gainst myself a lawful plea commence: Such civil war is in my love and hate That I an accessary needs must be To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me. |

|

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns and silver fountains mud; |

Worry no more about what you have done because nothing and nobody's perfect: the symbol of beauty itself, the rose, has thorns, and at the bottom of even the clearest fresh water fountain you will find mud which you only need to stir a bit to take off its silvery sheen.

'No rose without a thorn', as editors generally point out, is of course a proverb stating a generally accepted fact of life that everything has its downside, and this here includes you, and, as we shall see in a moment, me too. |

|

Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun

And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud. |

Both the Moon and the Sun get obscured by clouds and sometimes by eclipses, and even the sweetest, as in loveliest, but also here probably most fragrant, flower may be afflicted by a canker, which is a caterpillar or other insect larva or worm that eats and thus defiles flowers.

'The canker soonest eats the fairest rose' is also proverbial, and so another generally accepted truth is here simply rehearsed. |

|

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorising thy trespass with compare, |

Everyone has their fault, and even I am right now showing my own weakness and therefore fault, because by comparing your misdeed to these general truths about life I appear to be giving you licence to commit them.

|

|

Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss,

Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are; |

In doing so I actually corrupt myself, because I do know right from wrong, and yet still I try to absolve you from your crime, making more excuses for the sins you have committed than they actually merit. In other words, I am fully aware of the fact that I am here defending the indefensible, really, but still I go out of my way to do so, and that is clearly a fault of mine.

The Quarto Edition here says: Excusing their sins more than their sins are But as we have noted on more than one occasion before, 'their' and 'thy' often get mixed up by the typesetter of this first edition which clearly is composited from a manuscript where the two words in either Shakespeare's handwriting or quite possibly the hand of someone who copied from his originals would look very similar and so most editors emend to 'thy' since this makes much more sense. |

|

For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense,

|

Because I try to make sense of your sensual fault, which is a sin of the flesh. 'Sensual' here as elsewhere in Shakespeare has a stronger meaning of lust and salaciousness than it has for us. In other words: I try to rationalise your actions which are completely irrational as they are driven purely by desire.

This is the closest we have as yet come to an explanation of what the young man has done: his trespass, his sin, his fault, as it has now been variously described, clearly has to do with a sexual escapade. This comes as little surprise, since much of the terminology leading up to this has been laden with moral censure, of course. |

|

Thy adverse party is thy advocate,

|

The person whom you have wronged – me, in a legal sense the party who is here the accuser and therefore adverse to you who you are the defendant in this constellation – is also your advocate who assists you in your defence:

|

|

And gainst myself a lawful plea commence:

|

I here with this poem start or instigate a legal plea on your behalf against myself, by citing these reasons why what you have done can be explained away, when in fact as the person who has been wronged I should be fighting my own corner and – before this invisible, metaphorical court that this poem assembles – argue my own case against you.

|

|

Such civil war is in my love and hate

|

And here is the reason why: because I am so torn between my love for you and my hatred for what you have done...

|

|

That I an accessary needs must be

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me. |

...that against my will or better judgment I have to become an accessary to you, the sweet – here again as in lovely – thief who robs me in this sour, as in anything but lovely, way.

An 'accessary' in the legal sense is "someone who gives assistance to the perpetrator of a crime without taking part in it," (Oxford Languages) and therefore implies an – in serious cases heavy – burden of shared guilt. And the juxtaposition of 'sweet' and 'sour' is heightened by putting the words 'thief' and 'rob' next to each other, because, as Colin Burrow points out, a thief normally steals, in the main without causing physical harm or injury or threat, literally by stealth, if at all possible undetected, whereas to rob someone is an openly aggressive act of appropriation. |

With his tormented, paradoxical, and sensationally revealing Sonnet 35, William Shakespeare absolves the young man of his misdeed and puts what has happened down to nothing in the world being perfect, not even he. It is the third in this set of three sonnets that might be considered a triptych, and with it, Shakespeare appears to resign himself into the triangular complexity his relationship with the young man has acquired, while dropping a nugget of information that to us comes as something of a poetic bombshell.

Shakespeare has relinquished his anger, and even – though it still reverberates through these lines too – his disappointment. The "base clouds" of Sonnets 33 and 34 are here just ordinary clouds that do what clouds do, as a matter of ordinary course, stain the sun and the moon as well, now and then, and these two both, the moon and the sun, may be hidden briefly by eclipses occasionally, which might to some appear to portend ill, but which are in fact just a fact of cosmic life. Yes, this is a stain on the celestial bodies – and remember of course that I have likened you to the sun: my sun, who one early morn did shine on me – and yes, the canker that lives in the sweetest buds is loathsome, but who am I to wonder, in a way, that these worms seek out you, when the proverb itself predicts that this will happen.

And yes, I am about to tie myself up in knots with my own contorted argument, but I am aware of it, and I too am only human: "all men make faults," and this is mine. I, although I am the person who has been wronged here, find myself stepping up to the bar in my own courtroom and making the argument for you; and I can also tell you why, because I am torn between my great love for you and my abject hatred of what you have done.

And once again, we find ourselves in a situation that is all too human, and once again it makes sense on oh so many levels: I, the poet, William Shakespeare am infatuated, besotted, in love with this young man, and he has indicated – we got the impression – once or twice before that he is not to be taken for granted, nor is he to be told what to do. And while this sonnet still doesn't yet tell us what he has actually done specifically, it does now drop strong hints: the words that stand out here are 'trespass', 'sins', and 'sensual fault', none of which points at the young man having pinched an orange.

That the bad weather of these sonnets has come about by an act of appropriation is also clear now: you are the "sweet thief which sourly robs from me." And seeing that you are – as everything we have seen and heard so far suggests and nothing we have seen and heard so far makes us doubt – immeasurably richer, better positioned in society, and more highly regarded than me, what you have taken from me is hardly going to be my money, my house, my horse, or my pen.

This 'sensual fault' to which I find myself forced to bring – and in doing so make of it – some sense, is clearly, obviously, and really rather unambiguously a sexual transgression, and because it involves a theft or even a robbery, it can only mean one or, at least theoretically, though hardly in practice, both of two things: either the young man has slept with William Shakespeare's wife, or he has done so with somebody else whom William Shakespeare considers to be rightfully his, or both. This would explain a great deal: the dejected disappointment of Sonnet 33 and the visceral anger of Sonnet 34 would make sense even if the young man had simply gone and got his rocks off with someone else: if I consider myself to be in a relationship with you and you go off and play elsewhere, then unless we are from the outset in an open relationship, I could be forgiven for feeling hurt and betrayed and utterly deflated. But that is not a theft. That is 'simply' or, if one wants to put it thus, 'merely' a betrayal. Here though we have it in writing that the young man has stolen something from Will and it is not something trivial, nor is it something material, nor is it something spiritual, or metaphorical. And it is extremely unlikely to be Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway, who lives two day's ride away in Stratford-upon-Avon, surrounded by family and friends. So who is it?

If this Sonnet 35 – which, although it can stand on its own – we really need to consider in the context of Sonnets 33 and 34, asks one pertinent question it is this: whom has the young man taken from Shakespeare? Up until now, we have had zero indication that William Shakespeare, apart from the young man, had any lovers or affairs concurrently with the one he is so passionately conducting with the young man. In fact, as recently as Sonnet 31, he told the young man:

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I, by lacking, have supposed dead

And then:

Their images I loved I view in thee

And thou, all they, hast all the all of me.

Up until this sonnet, we were given to believe that Shakespeare is entirely and exclusively – with the exception, always, of his wife in Stratford – devoted to the young man. But in order for the young man to have caused this commotion in Shakespeare's heart by taking someone from him, he, Shakespeare, must have had someone else all this time.

And if that is the one pertinent question this sonnet asks, it moves another question an appreciable nudge closer towards being answered. Not yet conclusively, but with increasing credibility. Also in Sonnet 31, we received the impression that puns were being placed, and hints being hidden in not particularly well-shielded spots, that the relationship between Shakespeare and his young man had by then acquired a physical, quite possibly sexual dimension. There was no proof of this then and there is no proof of this now, but while the words themselves give us no certainty here, their tone and their constellation evoke the reaction not just of someone who finds out that his dear friend and platonic soulmate has deemed it necessary to get off with his extra-marital love interest, but that this dear friend and soulmate is also, quite in his own right, a lover.

We do find ourselves somewhat in the realm of speculation here, because who can tell exactly how I, as the poet, would express myself in either of these two scenarios: the one where my beautiful young lover is just that, or the one where he is simply somebody I have idolised to the point of practically fantasising about him, but where our relationship really is that of a very close friendship, and nothing more.

Things will become quite a bit clearer soon, though not immediately. Somewhat vexingly, Shakespeare is either taking a short detour next, through four sonnets which seem to have little to do directly with this crisis, although at least Sonnet 36 may still be informed by it, or the order of the sonnets has here got jumbled up a bit and what was next written was in fact Sonnet 40 which seems to most directly connect with the current state of affairs. And this state of affairs, in more than one sense, does rather leave us with something of a cliffhanger, because it is not until then – Sonnets 40, 41, and 42 – that we will be getting further and beyond our immediate expectations fascinating answers.

Shakespeare has relinquished his anger, and even – though it still reverberates through these lines too – his disappointment. The "base clouds" of Sonnets 33 and 34 are here just ordinary clouds that do what clouds do, as a matter of ordinary course, stain the sun and the moon as well, now and then, and these two both, the moon and the sun, may be hidden briefly by eclipses occasionally, which might to some appear to portend ill, but which are in fact just a fact of cosmic life. Yes, this is a stain on the celestial bodies – and remember of course that I have likened you to the sun: my sun, who one early morn did shine on me – and yes, the canker that lives in the sweetest buds is loathsome, but who am I to wonder, in a way, that these worms seek out you, when the proverb itself predicts that this will happen.

And yes, I am about to tie myself up in knots with my own contorted argument, but I am aware of it, and I too am only human: "all men make faults," and this is mine. I, although I am the person who has been wronged here, find myself stepping up to the bar in my own courtroom and making the argument for you; and I can also tell you why, because I am torn between my great love for you and my abject hatred of what you have done.

And once again, we find ourselves in a situation that is all too human, and once again it makes sense on oh so many levels: I, the poet, William Shakespeare am infatuated, besotted, in love with this young man, and he has indicated – we got the impression – once or twice before that he is not to be taken for granted, nor is he to be told what to do. And while this sonnet still doesn't yet tell us what he has actually done specifically, it does now drop strong hints: the words that stand out here are 'trespass', 'sins', and 'sensual fault', none of which points at the young man having pinched an orange.

That the bad weather of these sonnets has come about by an act of appropriation is also clear now: you are the "sweet thief which sourly robs from me." And seeing that you are – as everything we have seen and heard so far suggests and nothing we have seen and heard so far makes us doubt – immeasurably richer, better positioned in society, and more highly regarded than me, what you have taken from me is hardly going to be my money, my house, my horse, or my pen.

This 'sensual fault' to which I find myself forced to bring – and in doing so make of it – some sense, is clearly, obviously, and really rather unambiguously a sexual transgression, and because it involves a theft or even a robbery, it can only mean one or, at least theoretically, though hardly in practice, both of two things: either the young man has slept with William Shakespeare's wife, or he has done so with somebody else whom William Shakespeare considers to be rightfully his, or both. This would explain a great deal: the dejected disappointment of Sonnet 33 and the visceral anger of Sonnet 34 would make sense even if the young man had simply gone and got his rocks off with someone else: if I consider myself to be in a relationship with you and you go off and play elsewhere, then unless we are from the outset in an open relationship, I could be forgiven for feeling hurt and betrayed and utterly deflated. But that is not a theft. That is 'simply' or, if one wants to put it thus, 'merely' a betrayal. Here though we have it in writing that the young man has stolen something from Will and it is not something trivial, nor is it something material, nor is it something spiritual, or metaphorical. And it is extremely unlikely to be Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway, who lives two day's ride away in Stratford-upon-Avon, surrounded by family and friends. So who is it?

If this Sonnet 35 – which, although it can stand on its own – we really need to consider in the context of Sonnets 33 and 34, asks one pertinent question it is this: whom has the young man taken from Shakespeare? Up until now, we have had zero indication that William Shakespeare, apart from the young man, had any lovers or affairs concurrently with the one he is so passionately conducting with the young man. In fact, as recently as Sonnet 31, he told the young man:

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I, by lacking, have supposed dead

And then:

Their images I loved I view in thee

And thou, all they, hast all the all of me.

Up until this sonnet, we were given to believe that Shakespeare is entirely and exclusively – with the exception, always, of his wife in Stratford – devoted to the young man. But in order for the young man to have caused this commotion in Shakespeare's heart by taking someone from him, he, Shakespeare, must have had someone else all this time.

And if that is the one pertinent question this sonnet asks, it moves another question an appreciable nudge closer towards being answered. Not yet conclusively, but with increasing credibility. Also in Sonnet 31, we received the impression that puns were being placed, and hints being hidden in not particularly well-shielded spots, that the relationship between Shakespeare and his young man had by then acquired a physical, quite possibly sexual dimension. There was no proof of this then and there is no proof of this now, but while the words themselves give us no certainty here, their tone and their constellation evoke the reaction not just of someone who finds out that his dear friend and platonic soulmate has deemed it necessary to get off with his extra-marital love interest, but that this dear friend and soulmate is also, quite in his own right, a lover.

We do find ourselves somewhat in the realm of speculation here, because who can tell exactly how I, as the poet, would express myself in either of these two scenarios: the one where my beautiful young lover is just that, or the one where he is simply somebody I have idolised to the point of practically fantasising about him, but where our relationship really is that of a very close friendship, and nothing more.

Things will become quite a bit clearer soon, though not immediately. Somewhat vexingly, Shakespeare is either taking a short detour next, through four sonnets which seem to have little to do directly with this crisis, although at least Sonnet 36 may still be informed by it, or the order of the sonnets has here got jumbled up a bit and what was next written was in fact Sonnet 40 which seems to most directly connect with the current state of affairs. And this state of affairs, in more than one sense, does rather leave us with something of a cliffhanger, because it is not until then – Sonnets 40, 41, and 42 – that we will be getting further and beyond our immediate expectations fascinating answers.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!