Sonnet 82: I Grant Thou Wert Not Married to My Muse

|

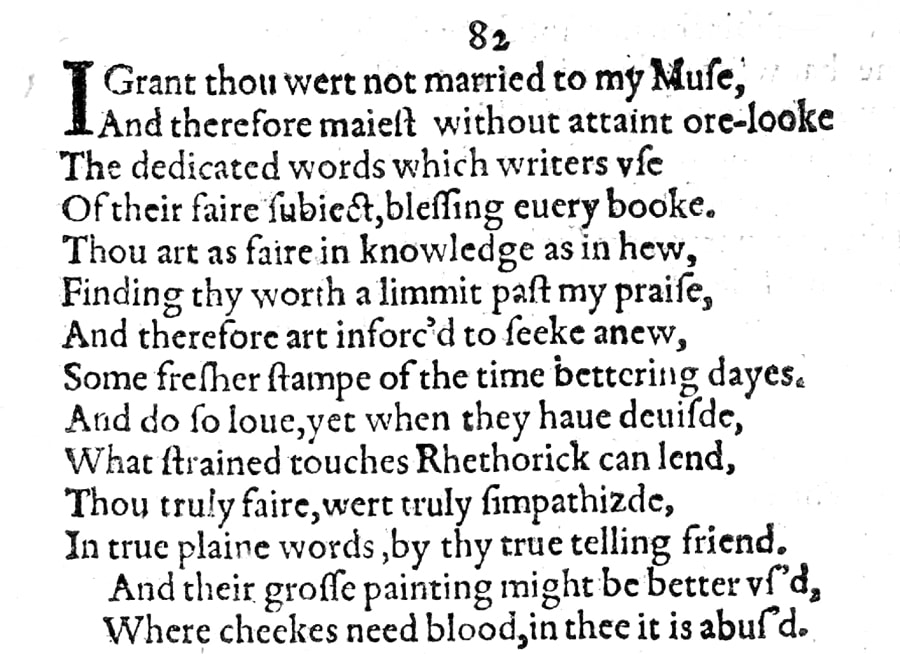

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse

And therefore mayst without attaint orelook The dedicated words which writers use Of their fair subject, blessing every book. Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue, Finding thy worth a limit past my praise, And therefore art enforced to seek anew Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days. And do so, love, yet when they have devised What strained touches rhetoric can lend, Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised In true plain words by thy true-telling friend, And their gross painting might be better used Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused. |

|

I grant thou wert not married to my Muse

|

I grant – as in admit or allow for the fact – that you were not married to my Muse.

'Muse' in this instance again stands for the poet's output in writing, in other words the product of his inspiration. It is a term that Shakespeare uses on other occasions to mean the poet himself, such as in Sonnet 21: So is it not with me as with that Muse, Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse, and he also uses it to mean the inspiration or indeed the goddess associated with it, as in Sonnet 38: Be thou the tenth Muse, ten times more in worth Than those old nine which rhymers invocate. Here it is obvious that "my Muse" is Shakespeare's poetry, and by employing the word 'married', he draws a particularly strong link between this and the young man and therefore by association between the young man and himself. The line might almost as well be understood to mean: 'I grant you were not married to me', and this, in view of Sonnet 74 – "When thou reviewest this thou dost review | The very part was consecrate to thee," and the incredibly famous Sonnet 116, which is yet to come, "Let me not, to the marriage of true minds | Admit impediments" is surely significant. |

|

And therefore mayst without attaint orelook

The dedicated words which writers use Of their fair subject, blessing every book. |

And because of this, because you were never formally, let alone solemnly, committed to my writing – or to me, for that matter – you are at liberty to overlook, as in read, enjoy, consider, without any dishonour the words that other writers use when they dedicate their works to you, who you are the beautiful subject of their writing and who you with your presence in their writing thus bless every book that you feature in.

'Attaint' to mean a dishonour or a dishonourable reputation does have some sexual connotations, which, paired with the notion of marriage just above further emphasises a strong sense of Shakespeare feeling betrayed by his lover not only in matters concerning his poetry but also his love. 'Over-look' meanwhile may carry a hint of superficiality: to glance at something in a cursory manner, since it doesn't merit deep, full engagement. But Shakespeare also just used 'oreread' in the context of his own writing when he predicted, in Sonnet 81, that "Your monument shall be my gentle verse | Which eyes not yet created shall oreread," and while, as we noted, we can't be sure that Sonnet 81 finds itself in the right place in the collection and therefore directly before this one, we don't get a sense there of this 'over-reading' being a superficial treatment of his lines. Certainly 'orelook' is not to be confused with our contemporary 'overlook', meaning ignore or accidentally miss. Worth bearing in mind also is that the word 'book' in Shakespeare's day does not necessarily have to mean a bound volume of some standard size or dimension as we mostly understand it today. He uses the word here and elsewhere, for example in the early Sonnet 23, quite liberally to mean written matter, and so these books here referred to may just be comparatively small collections of loose-leaf, handwritten poetry. |

|

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise |

You are as 'beautiful' in your knowledge and thus your mind as you are in your appearance, and so you find yourself in a realm or a region that lies beyond my capacity or ability to praise you...

Several times in the series we have come across this idea – strongly present in classical and therefore Renaissance thinking – that in the ideal person an external beauty is matched by an internal beauty, which would express itself in wise, fair judgment, in considered argumentation, in kind actions towards others and generally upright behaviour. So there is a double meaning at work here of 'fair' to mean both 'beautiful' and 'fair-minded'. And on several previous occasions we could not entirely believe William Shakespeare when he credited his young lover with such elevated qualities of character, considering some of the things the young man clearly has done and very likely has said. Here too, we are possibly entitled to wonder whether Shakespeare is not simply flattering his young man, making excuses for him, possibly because there is rather a lot at stake and he effectively has to do so, if he does not want to lose him entirely. But we will give this particular thought some more consideration when we discuss the poem in a bit more detail below. |

|

And therefore art enforced to seek anew

Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days. |

...and so because of this you are not only allowed but in fact forced to look out for a new, fresher imprint or representation of these ever improving times. In other words, my poetry can no longer do you justice and so you are obviously forced to find a poet or poets who can move with the times and write in a style that is more in keeping with the fashion of the day.

This too is a recurring theme: Shakespeare appears to be getting admonished for not being 'inventive' or 'modern' enough in his language. Sonnet 76 made this abundantly clear and also offered a reason for it: Why is my verse so barren of new pride, So far from variation or quick change? Why, with the time, do I not glance aside To new-found methods and to compounds strange? The answer is simply this: O know, sweet love, I always write of you And you and love are still my argument. 'Stamp' is an interesting concept to deploy in this context, and editors emphasise the to us most obvious meaning of 'printing press' and therefore here by extension 'printed matter', but it can also mean 'character', and of course it may further allude to a seal of approval or official recognition from an outside authority, such as one would find on a marriage certificate, for example. |

|

And do so, love, yet when they have devised

What strained touches rhetoric can lend, |

And do so, my love, do overlook these other writers' works and find yourself these 'fresher', more up-to-date expressions of admiration for you, but when these other poets have devised or put together or come up with whatever strained, elaborate, possibly far-fetched phrases and poetic flourishes that the art of rhetoric can provide...

The dismissive tone here is unmistakable: Shakespeare characterises the poetry of these other writers as 'strained' meaning forced and artificial, and therefore untruthful. As far as he is concerned these other poets pull their flowery, over-ornamented language from the register of whatever happens to be in vogue at the moment without any real understanding of, or indeed love for, their subject, the young man. This is not something Shakespeare can admire or approve of, which he made clear as early as Sonnet 21: O let me, true in love, but truly write And then believe me, my love is as fair As any mother's child... A point he now makes again, only much more forcefully: |

|

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true plain words by thy true-telling friend, |

...then when you have done so, remember or know that you who are truly beautiful were truly, as in truthfully 'sympathised' meaning represented, portrayed, in true, plain words, by me, your true-telling friend: I am the poet who genuinely knows and loves you and who writes to and for you in plain true words, that speak of nothing but my authentic admiration and love for you.

This in itself is true, though only partially. What is absolutely true is that Shakespeare really never goes into any overblown or cliched description of his young lover, something that his young lover appears to hold against him, as will become even clearer in the next sonnet which is closely tied to this one, but he does on occasion make him look better than his conduct most likely deserves, especially, as in this particular sonnet, when he talks of the young man's unimpeachable character. |

|

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood: in thee it is abused. |

And these other poets' gross – as in exaggerated, hyperbolic, over-the-top – descriptions of you might be better used for people who need this kind of writing because their own faces are so lacking in natural beauty that only the flattery and fawning of a poet can make them look good. 'Painting' here once again is of course a verbal portrait, rather than a pictorial one, these being poets and therefore painters in words. Both, Sonnets 53 and 67 also use it in this sense.

'Cheek' here, as in Sonnets 67 & 68, stands for 'face', and the fact that these cheeks here referred to need blood means that they are old and gaunt and devoid of youthful sap and beauty. |

With Sonnet 82, William Shakespeare resumes his discussion with the young man of his own status as a poet in the young man's life, attempting a conciliatory, even sympathetic tone which purports to encourage his lover to by all means have a look at other people's writing too, but draws the clearest distinction yet in this group between the authentic nature of his own writing and the soulless artifice of his rivals, whom he here once more speaks of in a generalised plural.

The sonnet can stand on its own, but it sets up an argument that is then picked up by Sonnet 83 – where he again will make it clear that there is really one rival involved – and then continues right into Sonnets 84 and 85 which all concern themselves with the young man's increasingly evident expectation to receive poetry that presents him in a particular light and that – as we would say today – ticks certain boxes: a requirement that Shakespeare feels unable to fulfil in the manner that others appear willing to comply with.

If we set aside Sonnet 81, which doesn't mention any rival poet or poetry, then Sonnet 82 thematically follows on from Sonnet 80 and immediately the most striking aspect to it is its categorically different tone. When Sonnet 80 was, or tried to be, playful, provocative – we ventured borderline 'saucy' – Sonnet 82 displays an almost sober reflection of how things are. Sonnet 80, following a melodramatic opening makes sport with its sailing and seafaring metaphor, coming down or – in that context possibly more appropriately – back to earth only really in the closing couplet which sounds therefore all the more sincere.

This wit and frivolity here has gone and makes way to more of a resigned sulk: when we say that Shakespeare here is 'attempting' a conciliatory note then 'attempt' is quite the operative term. He only partially succeeds. That he is being sincere in essence is not really in doubt. The second half of the third quatrain is Shakespeare at his rawest, purest self, driving home a point he has made – and clearly sensed he had to make – before:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true plain words by thy true-telling friend.

And even when he says things which to our ears sound a bit double-edged, so as not to call it sarcastic, we probably do well to remember just what the era was like in which he lived and loved. To us

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise

does sound a bit over the top, but this is an age when class, social status, education matter a great deal. Not everybody is schooled in the art of rhetoric, not everybody has what today we would call 'general knowledge', people generally – the common people, as it were – knew very little about the world indeed. What news they received came from town criers, pamphleteers, and through official edict. The rest was word of mouth. When it comes to education, we can't put an exact figure to what literacy levels were at, but estimates range from as low as 10% to as high as 30% of the population, whereby the upper limit here is probably somewhat optimistic and includes people who were at best partly able to read and write. Girls, generally, didn't go to school at all but might, if they were part of a well-to-do family get some education at home; boys, also really only from a financially affluent social middle layer upwards may – as William Shakespeare himself did – attend a grammar school and receive a classical education, while higher education was almost entirely the reserve of the upper social orders: the nobility, the clergy, and genuinely wealthy, well-situated families.

So being "as fair in knowledge as in hue" is not trivial. And it really also goes beyond the congruence of body and spirit, of external and internal beauty, that we already mentioned. What Shakespeare seems to be saying to the young man is that he acknowledges his elevated status also in terms of his education and with it his ability to put that education to use, because absolutely core to the classical education is rhetoric. Not as we understand it today to mean a somewhat dubious, often deceitful deployment of language for mostly political advantage, but rhetoric as the ancient art of persuasion: the skilful, methodical application of language to construct sound arguments that can win a case in court or convince your fellow citizens of the need for a certain course of action, and the beautiful, pleasing arrangement of words in a way that is able to delight the eye and ear. The young man is portrayed as someone who is well-versed in rhetoric, and indeed for him in his era to be at all appreciative of poets and their poetry, he would really have to be.

That said, rhetoric, even then and to Shakespeare, is an art. And that means it is prone to produce artifice. The 'strained touches' that 'rhetoric can lend' may constitute skilful, expert poetry, but compared to what I, your true-telling friend, put down in true, plain words, they are meaningless waffle. And this matters a great deal.

We already cited Sonnet 21. Sonnet 66 also – and forcefully – touches on the same theme, it launches itself with

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry:

and then enumerates eleven ills of the world that we all still fully recognise today, of which number ten is

And simple truth miscalled simplicity.

William Shakespeare's frustration with this is not new and not slight: time and again he has to make the point that the poet who speaks a plain, simple truth, is not a simpleton. And for Shakespeare this is something of a sore point. The famous 'upstart crow' insult by Robert Greene, which we mentioned on at least a couple of occasions, goes to the heart of this: he is not a 'university wit', he is, very likely educationally as well as financially and socially, the young man's inferior and so it perhaps wouldn't take much to trigger in him a strong, deeply felt, personal reaction.

We occasionally bring to mind the fact that not only do these sonnets not stand in isolation from each other, but they also do not form a continuous one-way communication. They are, at least some of them, clearly part of a dialogue; they are written, quite often, in response to something that has been said or that has happened, and it is very easy to imagine the kind of comments a young nobleman with an appreciably sized ego might make to his poet friend who not only is from a signally lower social class, and financially way below his league, but also at least a good ten years older at a time when – as we saw – ten, twelve years make a huge difference and who has somehow acquired all his poetry by self-study, practice, and what some people might consider a God-given genius, what more universally we would possibly today describe as an innate talent and a very good ear for language.

The second noteworthy thing about Sonnet 82 we already mentioned: when Shakespeare says to his young man "thou wert not married to my Muse," then that really is quite telling, so as not to claim revealing. Our contention that this whole group of Rival Poet Sonnets is not just about the young man's appreciation of Will as a writer but about the essential nature of their relationship is already virtually beyond doubt and will become even more plainly obvious with the sonnets that follow. And this conflation of the poet the professional and William Shakespeare the lover makes perfect sense, because unlike the young man, William Shakespeare is married to his own Muse, he is his poetry; he says so, as recently as Sonnet 74, which we quoted above once before: "My life hath in this line some interest," he says. and he then goes on to make it absolutely clear that his poetry, which expresses his soul, or, as he calls it, his spirit, is the thing that makes him who he is, not his body or his physical presence on earth:

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

One more thing I should mention, not least because I made such a big deal of it when talking about Sonnet 80: with Sonnet 82, Shakespeare reverts back to 'thou'. There can be – as I pointed out at the time – no question as to whether this sonnet might not just be addressed to someone other than Sonnet 80. Clearly it isn't. But just in case you have lingering doubts and you think, what does he know, plus he completely ignores Sonnet 81 which is wedged in-between and which also is addressed to 'you': Sonnet 83, which picks up directly and immediately from the closing thought of Sonnet 82, switches back to 'you' again:

This is how Sonnets 82 and 83 link up:

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.

I never saw that you did painting need,

And therefore to your fair no painting set,

I rest my case.

The sonnet can stand on its own, but it sets up an argument that is then picked up by Sonnet 83 – where he again will make it clear that there is really one rival involved – and then continues right into Sonnets 84 and 85 which all concern themselves with the young man's increasingly evident expectation to receive poetry that presents him in a particular light and that – as we would say today – ticks certain boxes: a requirement that Shakespeare feels unable to fulfil in the manner that others appear willing to comply with.

If we set aside Sonnet 81, which doesn't mention any rival poet or poetry, then Sonnet 82 thematically follows on from Sonnet 80 and immediately the most striking aspect to it is its categorically different tone. When Sonnet 80 was, or tried to be, playful, provocative – we ventured borderline 'saucy' – Sonnet 82 displays an almost sober reflection of how things are. Sonnet 80, following a melodramatic opening makes sport with its sailing and seafaring metaphor, coming down or – in that context possibly more appropriately – back to earth only really in the closing couplet which sounds therefore all the more sincere.

This wit and frivolity here has gone and makes way to more of a resigned sulk: when we say that Shakespeare here is 'attempting' a conciliatory note then 'attempt' is quite the operative term. He only partially succeeds. That he is being sincere in essence is not really in doubt. The second half of the third quatrain is Shakespeare at his rawest, purest self, driving home a point he has made – and clearly sensed he had to make – before:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true plain words by thy true-telling friend.

And even when he says things which to our ears sound a bit double-edged, so as not to call it sarcastic, we probably do well to remember just what the era was like in which he lived and loved. To us

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise

does sound a bit over the top, but this is an age when class, social status, education matter a great deal. Not everybody is schooled in the art of rhetoric, not everybody has what today we would call 'general knowledge', people generally – the common people, as it were – knew very little about the world indeed. What news they received came from town criers, pamphleteers, and through official edict. The rest was word of mouth. When it comes to education, we can't put an exact figure to what literacy levels were at, but estimates range from as low as 10% to as high as 30% of the population, whereby the upper limit here is probably somewhat optimistic and includes people who were at best partly able to read and write. Girls, generally, didn't go to school at all but might, if they were part of a well-to-do family get some education at home; boys, also really only from a financially affluent social middle layer upwards may – as William Shakespeare himself did – attend a grammar school and receive a classical education, while higher education was almost entirely the reserve of the upper social orders: the nobility, the clergy, and genuinely wealthy, well-situated families.

So being "as fair in knowledge as in hue" is not trivial. And it really also goes beyond the congruence of body and spirit, of external and internal beauty, that we already mentioned. What Shakespeare seems to be saying to the young man is that he acknowledges his elevated status also in terms of his education and with it his ability to put that education to use, because absolutely core to the classical education is rhetoric. Not as we understand it today to mean a somewhat dubious, often deceitful deployment of language for mostly political advantage, but rhetoric as the ancient art of persuasion: the skilful, methodical application of language to construct sound arguments that can win a case in court or convince your fellow citizens of the need for a certain course of action, and the beautiful, pleasing arrangement of words in a way that is able to delight the eye and ear. The young man is portrayed as someone who is well-versed in rhetoric, and indeed for him in his era to be at all appreciative of poets and their poetry, he would really have to be.

That said, rhetoric, even then and to Shakespeare, is an art. And that means it is prone to produce artifice. The 'strained touches' that 'rhetoric can lend' may constitute skilful, expert poetry, but compared to what I, your true-telling friend, put down in true, plain words, they are meaningless waffle. And this matters a great deal.

We already cited Sonnet 21. Sonnet 66 also – and forcefully – touches on the same theme, it launches itself with

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry:

and then enumerates eleven ills of the world that we all still fully recognise today, of which number ten is

And simple truth miscalled simplicity.

William Shakespeare's frustration with this is not new and not slight: time and again he has to make the point that the poet who speaks a plain, simple truth, is not a simpleton. And for Shakespeare this is something of a sore point. The famous 'upstart crow' insult by Robert Greene, which we mentioned on at least a couple of occasions, goes to the heart of this: he is not a 'university wit', he is, very likely educationally as well as financially and socially, the young man's inferior and so it perhaps wouldn't take much to trigger in him a strong, deeply felt, personal reaction.

We occasionally bring to mind the fact that not only do these sonnets not stand in isolation from each other, but they also do not form a continuous one-way communication. They are, at least some of them, clearly part of a dialogue; they are written, quite often, in response to something that has been said or that has happened, and it is very easy to imagine the kind of comments a young nobleman with an appreciably sized ego might make to his poet friend who not only is from a signally lower social class, and financially way below his league, but also at least a good ten years older at a time when – as we saw – ten, twelve years make a huge difference and who has somehow acquired all his poetry by self-study, practice, and what some people might consider a God-given genius, what more universally we would possibly today describe as an innate talent and a very good ear for language.

The second noteworthy thing about Sonnet 82 we already mentioned: when Shakespeare says to his young man "thou wert not married to my Muse," then that really is quite telling, so as not to claim revealing. Our contention that this whole group of Rival Poet Sonnets is not just about the young man's appreciation of Will as a writer but about the essential nature of their relationship is already virtually beyond doubt and will become even more plainly obvious with the sonnets that follow. And this conflation of the poet the professional and William Shakespeare the lover makes perfect sense, because unlike the young man, William Shakespeare is married to his own Muse, he is his poetry; he says so, as recently as Sonnet 74, which we quoted above once before: "My life hath in this line some interest," he says. and he then goes on to make it absolutely clear that his poetry, which expresses his soul, or, as he calls it, his spirit, is the thing that makes him who he is, not his body or his physical presence on earth:

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

One more thing I should mention, not least because I made such a big deal of it when talking about Sonnet 80: with Sonnet 82, Shakespeare reverts back to 'thou'. There can be – as I pointed out at the time – no question as to whether this sonnet might not just be addressed to someone other than Sonnet 80. Clearly it isn't. But just in case you have lingering doubts and you think, what does he know, plus he completely ignores Sonnet 81 which is wedged in-between and which also is addressed to 'you': Sonnet 83, which picks up directly and immediately from the closing thought of Sonnet 82, switches back to 'you' again:

This is how Sonnets 82 and 83 link up:

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.

I never saw that you did painting need,

And therefore to your fair no painting set,

I rest my case.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!