Sonnet 38: How Can My Muse Want Subject to Invent

|

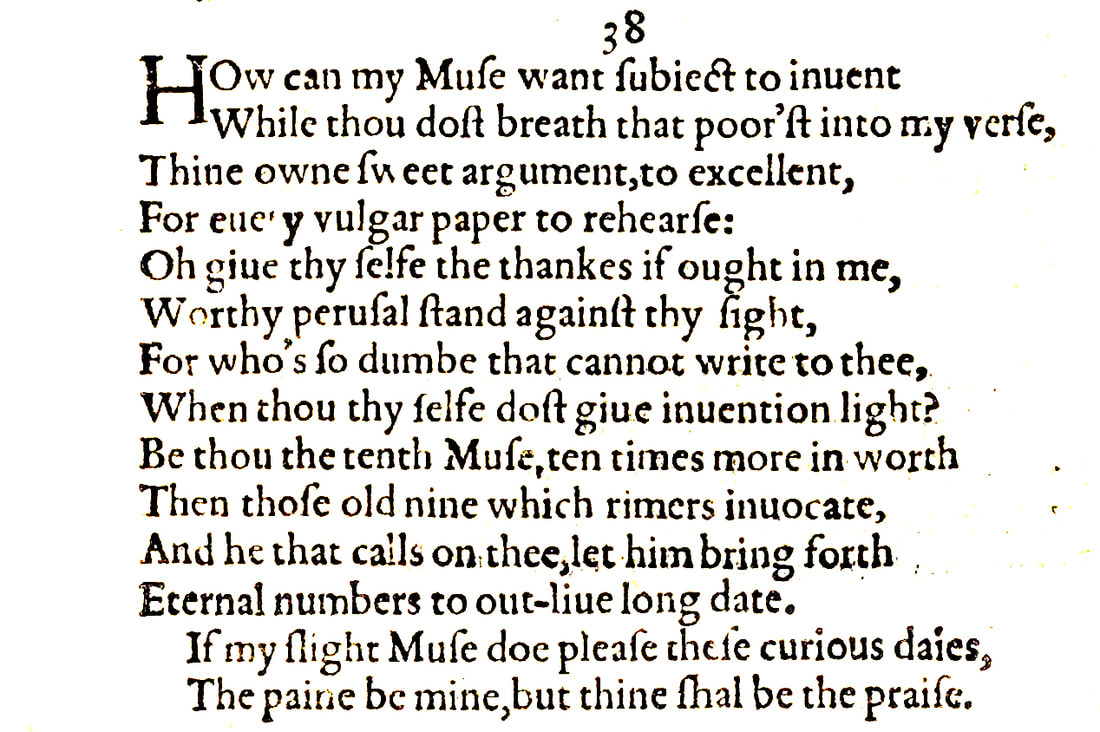

How can my Muse want subject to invent

While thou dost breathe that pourst into my verse Thine own sweet argument, too excellent For every vulgar paper to rehearse: O give thyself the thanks if ought in me Worthy perusal stand against thy sight, For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee, When thou thyself dost give invention light? Be thou the tenth Muse, ten times more in worth Than those old nine which rhymers invocate, And he that calls on thee, let him bring forth Eternal numbers to outlive long date. If my slight Muse do please these curious days, The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise. |

|

How can my Muse want subject to invent

|

How can I lack inspiration to compose poetry to you...

'Muse' is the ability to create, originally both through inspiration and also through skill or technique, though today we use it mainly in the former sense. It stems of course from the nine Muses, which are referenced later in the poem, who in Greek mythology are the goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. The use of the verb 'invent' is telling: in ancient rhetoric, 'invention' from Latin inventio refers the construction of an argument and has less to do with making things up than finding good, valid evidence or topics to support one's contention. The fact that Shakespeare knows and applies this vocabulary here in its technical sense points to his classical education back in Stratford. |

|

While thou dost breathe that pourst into my verse

Thine own sweet argument, too excellent For every vulgar paper to rehearse: |

...while you live and by your presence on this planet and in my life pour into my verse your very own argument, which is too excellent – for which read 'exquisite' as well as 'perfectly constructed': both qualities you yourself are eminently noted for – than that just any ordinary piece of paper could or should regurgitate it.

The terminology from classical rhetoric continues: the young man by his mere presence provides the argument a rhetorician, such as a poet, needs, and it is an 'excellent' argument, meaning that it stands up to scrutiny: it is well composed, it pleases the mind and the ear and the eye. Fascinating is the assertion that this argument is not only outstandingly good but too good for any 'vulgar paper' to rehearse'. 'Vulgar' here as elsewhere in Shakespeare mostly simply means 'ordinary' or 'base', but what is of interest is that he appears to be suggesting that other, less skilled and therefore by implication less deserving poets or scribes might feel tempted to eulogise the young man or have already done so. This is a theme that will come to the fore in a while with the 'Rival Poet' sequence that is generally accepted to encompass Sonnets 78 to 86, but it has been foreshadowed tentatively once before, in Sonnet 21. |

|

O give thyself the thanks if ought in me

Worthy perusal stand against thy sight, |

O, thank yourself if anything that I have to offer is worth looking at and comes before your eyes and also, more to the point, stands up to your close inspection or scrutiny, in other words, meets with your approval...

|

|

For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee

When thou thyself dost give invention light? |

Because who is so dull or inarticulate that they are unable to write to you, when you yourself give such inspiration to the composition of a rhetorical piece, such as a clearly structured poem?

'Dumb' to mean 'stupid' is an Americanism that does not directly apply here, though implied in this inarticulacy and dullness is of course also a lack of intellectual acuity. |

|

Be thou the tenth Muse, ten times more in worth

Than those old nine which rhymers invocate, |

May you be the tenth Muse, and as the tenth one also ten times more in worth – meaning more powerful, stronger, more worthy – than the classical nine Muses which poets invoke when they write their poetry.

In the ancient tradition, a poet would call on their Muse to inspire, aid and guide them, so they may be able to produce a truthful poem that pleases the ear and conveys the story they have to tell with lasting power. Homer, for example, starts his Illiad with a direct address to the Muse: Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus' son Achilles, [...] Begin, Muse, when the two first broke and clashed, Agamemnon, lord of men, and brilliant Achilles. But William Shakespeare – as he already hinted at with 'every vulgar paper' does not have the great poets of antiquity, or indeed substantial contemporaries of his in mind: calling the people he is referring to 'rhymers' is deliberately deprecatory. A 'rhymer' to a 'poet' might be approximately as a 'scribbler' to a 'writer' or a 'fiddler' to a 'violinist'. |

|

And he that calls on thee, let him bring forth

Eternal numbers to outlive long date. |

And any such 'rhymer', let him – as it would at the time in the vast majority of cases be and as Shakespeare clearly assumes – produce endless streams of poetry that will last beyond the end of time.

We have seen 'date' to mean 'final date' or 'expiry date' before and here the 'long date' is, by implication, the longest date of expiry imaginable, in other words, the end of time. This of course references directly the instances in which I, the poet, have predicted that my poetry to you will live forever and in doing so give life to you, such as, most prominently, in Sonnet 18: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. |

|

If my slight Muse do please these curious days,

The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise. |

And Shakespeare ends with a hint of possibly, if not false then self-effacing, modesty in stark contrast to such earlier instances as Sonnet 18:

If my inconsiderable, inconsequential poetry – Muse here stands for the product that the Muse has inspired – should please these days that are so notoriously difficult to please, then the effort to do so shall be mine, but the praise that may result from it entirely goes to you. 'Curious' arrives in Middle English from Latin 'curiosus', meaning 'careful', from 'cura', 'care', and here has this connotation not so much of 'strange' or 'unusual' as we would also define it, but of 'fastidious', 'highly critical', and therefore by extension 'hard to please'. Its use here seems to point in a slightly clandestine way at Shakespeare feeling un- or under-appreciated for his poetry, which again would tie in with his perception of himself as being "made lame by" – in Sonnet 37 – and, in Sonnet 29, "in disgrace with" Fortune, and indeed 'mens' eyes', such as his 'peers', some of whom, as we noted when looking at Sonnet 25, actively and publicly disparage him. |

With his remarkably deadpan Sonnet 38, William Shakespeare changes tone completely and positions his own poetry as the product of the man who has so long now been his Muse. Like Sonnet 37, it does not obviously fit into the sequence, but like Sonnet 37, it still clearly speaks to the same young man and also like Sonnet 37, it references topics that have been expressed earlier in the series: in this case the particular relationship that exists between a poet and the person he is inspired by to write poetry for, something that has been addressed as early as Sonnet 21, where Shakespeare compared himself favourably to the kind of poet who sings his love's praises in unsubstantiated hyperbole.

Like Sonnet 37, Sonnet 38 does not so much reveal new insights to us as help us gain greater certainty about things that we have to continue to consider conjecture, since there can be no proof of anything other than of the existence of the words themselves. And, taking as read the young man's many exquisite qualities, the two elements that we can in this vein focus on are these:

There appears to be, not for the first time but more acutely felt than before, an awareness of other poets. This need hardly surprise us, since Shakespearean England is a land of poetry where the English language as we recognise it today for the first time really comes into its own and where poets can attain what today we might feel tempted to call – somewhat inadequately – 'celebrity' status. We know for as certain as we can know anything – not least from the previous Sonnet 37 – that by this time Shakespeare enjoys anything but that kind of status, and so it is especially interesting to hear here a tone creep in of borderline disdain towards other poets. As noted above and once before when this was the case in Sonnet 21, this is unlikely to be one specific 'rival poet' such as will make his presence felt later in the series, but when you hear a poet ask the question, "For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee," then even allowing for the fact that 'dumb' in the American sense of 'stupid' is not yet in circulation – not least because the first permanent English settlement in America was not founded until about a decade later, in 1607, in Jamestown, Virginia – we may be forgiven for detecting a note of condescension. In this, too, the sonnet echoes Sonnet 21, where the kind of poet there described is himself called a 'Muse' who is "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse," and we noted there what Shakespeare thinks of 'painted beauties', and so need not do so again here now.

The other element that comes through once more in Sonnet 38 is that Shakespeare either genuinely or rather more likely somewhat disingenuously disparages or at any rate diminishes his own poetry, calling it here "my slight Muse." We know that Shakespeare does not always and therefore probably not really think of his poetry as slight. There are several instances – some already mentioned, others yet to appear – when he has made it clear before and when he will make it clear again that his poetry is potent and has the power to bestow life and reality on the young man until long after either man's death and for many generations yet to come. So the slightly peeved tone that we seem to perceive here must stem from something else, and the obvious cause for it is other people's appraisal of his poetry.

Shakespeare – rather uncharacteristically, one might feel tempted to say, though that would be simplifying and reducing him to a less complex character than he clearly is – here comes across as borderline passive-aggressive: oh don't mind me and my little poems that I scribble: they are but a trifle of no import at all. Evidently not the case.

When we said about Sonnet 37 that in several places it tallies with what we think we know of William Shakespeare and his young man, then, similarly, Sonnet 38 tallies with what we think we can know about Shakespeare and the world of poets he is both a part of and yet not part of enough to feel he belongs there. This is of great significance in itself, because he is after all a poet trying to make it in London: the capital city of a fast growing culture and language. And interesting in this context is his use of the word 'Muse': it appears three times. First, to mean 'artistic capacity' or 'inspiration', and is deployed to ask the rhetorical question, how can this be in need of a subject to create my rhetorical argument in poetry. Second, to mean 'god or goddess of artistry', as in the nine classical Muses, deployed to assign a role to the young man himself: the source of inspiration and subject of the rhetorical invention rolled into one. Third, to mean 'the product of my art', deployed to describe the poetry itself.

If, as we have reason to believe and as current scholarly opinion holds, Sonnet 38 is part of the larger group of sonnets that was composed in the mid 1590s, then this adds a poignant perspective, because in 1593 and 1594, William Shakespeare dedicates two long narrative poems to the young Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, who is then in his very early twenties, in fact he turns 20 in 1593, and as we know, Henry Wriothesley is one of our chief candidates for the young man of these sonnets. Dedicating a piece of poetry to a rich patron is nothing at all unusual in Elizabethan England, but the dedication that William Shakespeare writes to Henry Wriothesley for the second of the two poems is somewhat out of the ordinary:

"To the Right Honourable Henry Wriothesly, Earl of Southampton, and Baron of Tichfield.

The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end; whereof this pamphlet, without beginning, is but a superfluous moiety. The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater, my duty would show greater; meantime, as it is, it is bound to your lordship, to whom I wish long life, still lengthened with all happiness.

Your lordship's in all duty,

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE"

Again, it is meet and proper to point out that gushing dedications are at the time par for the course, and so even though this one sits right up there in the higher echelons of effusiveness, it still has to be read against the backdrop of a culture that is much more deferential and therefore more, and differently, verbose than ours.

All that said, it is worth bearing this dimension in mind: whether or not Henry Wriothesley is the Fair Youth, he is manifestly a young man whom Shakespeare has or wants to have a professional relationship with, in the sense that he has or wants his patronage. This is nothing at all untoward or unusual: it is one of few ways – the other principal one being the sale of published print – in which a poet can make a living. But it puts into focus this existential need a poet such as William Shakespeare has: for him writing poetry is not 'just' a pouring out of emotion, not 'just' a means of communicating love and desire, or passion and frustration, or anger and despair, it is not 'just' a way of passing long hours away from love or from home: it is a way of earning money and it is a way of establishing a reputation and a standing in the world.

If, all that said and all this considered, the young, insanely wealthy, stubbornly single, and arrestingly beautiful Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton and Baron of Titchfield is also the lover of Shakespeare and subject, addressee, and muse of these sonnets, then Sonnet 38 acquires a whole new level of complexity, because then – although we don't know the exact sequence of events – the loves and the labours, and indeed the labours of love of William Shakespeare are truly and quite inseparably entwined, though fortunately, they are not, and not for quite some time yet, and in a sense, through and because of this timeless poetry, never shall be, truly lost.

Like Sonnet 37, Sonnet 38 does not so much reveal new insights to us as help us gain greater certainty about things that we have to continue to consider conjecture, since there can be no proof of anything other than of the existence of the words themselves. And, taking as read the young man's many exquisite qualities, the two elements that we can in this vein focus on are these:

There appears to be, not for the first time but more acutely felt than before, an awareness of other poets. This need hardly surprise us, since Shakespearean England is a land of poetry where the English language as we recognise it today for the first time really comes into its own and where poets can attain what today we might feel tempted to call – somewhat inadequately – 'celebrity' status. We know for as certain as we can know anything – not least from the previous Sonnet 37 – that by this time Shakespeare enjoys anything but that kind of status, and so it is especially interesting to hear here a tone creep in of borderline disdain towards other poets. As noted above and once before when this was the case in Sonnet 21, this is unlikely to be one specific 'rival poet' such as will make his presence felt later in the series, but when you hear a poet ask the question, "For who's so dumb that cannot write to thee," then even allowing for the fact that 'dumb' in the American sense of 'stupid' is not yet in circulation – not least because the first permanent English settlement in America was not founded until about a decade later, in 1607, in Jamestown, Virginia – we may be forgiven for detecting a note of condescension. In this, too, the sonnet echoes Sonnet 21, where the kind of poet there described is himself called a 'Muse' who is "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse," and we noted there what Shakespeare thinks of 'painted beauties', and so need not do so again here now.

The other element that comes through once more in Sonnet 38 is that Shakespeare either genuinely or rather more likely somewhat disingenuously disparages or at any rate diminishes his own poetry, calling it here "my slight Muse." We know that Shakespeare does not always and therefore probably not really think of his poetry as slight. There are several instances – some already mentioned, others yet to appear – when he has made it clear before and when he will make it clear again that his poetry is potent and has the power to bestow life and reality on the young man until long after either man's death and for many generations yet to come. So the slightly peeved tone that we seem to perceive here must stem from something else, and the obvious cause for it is other people's appraisal of his poetry.

Shakespeare – rather uncharacteristically, one might feel tempted to say, though that would be simplifying and reducing him to a less complex character than he clearly is – here comes across as borderline passive-aggressive: oh don't mind me and my little poems that I scribble: they are but a trifle of no import at all. Evidently not the case.

When we said about Sonnet 37 that in several places it tallies with what we think we know of William Shakespeare and his young man, then, similarly, Sonnet 38 tallies with what we think we can know about Shakespeare and the world of poets he is both a part of and yet not part of enough to feel he belongs there. This is of great significance in itself, because he is after all a poet trying to make it in London: the capital city of a fast growing culture and language. And interesting in this context is his use of the word 'Muse': it appears three times. First, to mean 'artistic capacity' or 'inspiration', and is deployed to ask the rhetorical question, how can this be in need of a subject to create my rhetorical argument in poetry. Second, to mean 'god or goddess of artistry', as in the nine classical Muses, deployed to assign a role to the young man himself: the source of inspiration and subject of the rhetorical invention rolled into one. Third, to mean 'the product of my art', deployed to describe the poetry itself.

If, as we have reason to believe and as current scholarly opinion holds, Sonnet 38 is part of the larger group of sonnets that was composed in the mid 1590s, then this adds a poignant perspective, because in 1593 and 1594, William Shakespeare dedicates two long narrative poems to the young Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, who is then in his very early twenties, in fact he turns 20 in 1593, and as we know, Henry Wriothesley is one of our chief candidates for the young man of these sonnets. Dedicating a piece of poetry to a rich patron is nothing at all unusual in Elizabethan England, but the dedication that William Shakespeare writes to Henry Wriothesley for the second of the two poems is somewhat out of the ordinary:

"To the Right Honourable Henry Wriothesly, Earl of Southampton, and Baron of Tichfield.

The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end; whereof this pamphlet, without beginning, is but a superfluous moiety. The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater, my duty would show greater; meantime, as it is, it is bound to your lordship, to whom I wish long life, still lengthened with all happiness.

Your lordship's in all duty,

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE"

Again, it is meet and proper to point out that gushing dedications are at the time par for the course, and so even though this one sits right up there in the higher echelons of effusiveness, it still has to be read against the backdrop of a culture that is much more deferential and therefore more, and differently, verbose than ours.

All that said, it is worth bearing this dimension in mind: whether or not Henry Wriothesley is the Fair Youth, he is manifestly a young man whom Shakespeare has or wants to have a professional relationship with, in the sense that he has or wants his patronage. This is nothing at all untoward or unusual: it is one of few ways – the other principal one being the sale of published print – in which a poet can make a living. But it puts into focus this existential need a poet such as William Shakespeare has: for him writing poetry is not 'just' a pouring out of emotion, not 'just' a means of communicating love and desire, or passion and frustration, or anger and despair, it is not 'just' a way of passing long hours away from love or from home: it is a way of earning money and it is a way of establishing a reputation and a standing in the world.

If, all that said and all this considered, the young, insanely wealthy, stubbornly single, and arrestingly beautiful Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton and Baron of Titchfield is also the lover of Shakespeare and subject, addressee, and muse of these sonnets, then Sonnet 38 acquires a whole new level of complexity, because then – although we don't know the exact sequence of events – the loves and the labours, and indeed the labours of love of William Shakespeare are truly and quite inseparably entwined, though fortunately, they are not, and not for quite some time yet, and in a sense, through and because of this timeless poetry, never shall be, truly lost.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!