Sonnet 15: When I Consider Every Thing That Grows

|

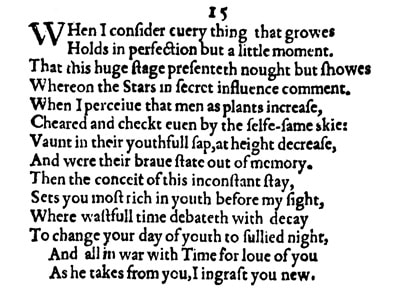

When I consider every thing that grows,

Holds in perfection but a little moment; That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows Whereon the stars in secret influence comment; When I perceive that men as plants increase, Cheered and checked, even by the self-same sky, Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease, And wear their brave state out of memory; Then the conceit of this inconstant stay Sets you most rich in youth before my sight, Where wasteful Time debateth with decay To change your day of youth to sullied night, And all in war with Time for love of you, As he takes from you, I engraft you new. |

|

When I consider every thing that grows,

|

When I consider every thing that grows...

Some editors emend 'every thing' to 'everything', but there is a subtle difference: 'everything' in one word is all things that exist, implying a mass of things. 'Every thing' also means all things that exist, but makes it clear that we are talking about individual things, here specifically things that can and do grow. And this will take on some significance imminently, as we shall see. |

|

Holds in perfection but a little moment,

|

...attains and keeps its perfect state only for a brief moment...

|

|

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

|

When I further consider that this huge stage that is the world does nothing but present us with plays...

The idea that all the world is a stage is one close to Shakespeare's heart, who famously has Jaques in As You Like it say as much: "All the world's a stage, / And all the men and women merely players." |

|

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

|

...upon which – these shows and therefore by necessity the players in them, us – the stars take their mysterious influence.

This subtly but nevertheless clearly references the previous Sonnet 14, where Shakespeare talked about what he calls 'astronomy', but what we today would think of as astrology: the ways in which the constellations and motions of the stars and the planets may or may not – but certainly are still today by many people and have always been widely believed to – have a direct impact on our fate. |

|

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

|

When I furthermore see how men grow just like plants...

By 'men' Shakespeare may well refer to all of humanity, because the words 'man' and 'men' do mean adult human beings in general as well, but there can be little doubt that he particularly has men in mind here, for a fairly male-specific reason, which is about to become clearer. |

|

Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky,

|

The same sky – with its stars that "comment" in their "secret influence" – cheers, as in cheers on, supports, enhances and checks, as in holds back, hinders, reduces the men on earth just as much as it does with the plants. In other words, we are all subject to the vagaries of a bigger nature that we cannot control.

Note that 'cheered' here is pronounced with two syllables, cheer-èd, and 'even' with one syllable, e'en in order for the line to scan. |

|

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease

|

The men, just like plants, show off the beauty and strength of their youth, when they are full of juice and sap and therefore life-force and energy, but just as they reach their climax, they start to shrivel and shrink.

Here is why Shakespeare may have men in mind in particular: he not only accurately describes what happens to plants and to human beings generally, but also to men's manhood when they have sex. |

|

And wear their brave state out of memory;

|

The brave state that men were in for such a short moment of glory is something they then, once it has passed, wear "out of memory," meaning it is quite forgotten. In other words: time passes quickly and everything in nature declines rapidly after having peaked and is then both out of sight and out of mind.

This, incidentally is one of those instances where strictly speaking we'd have to pronounce 'memory' as 'memoray' to rhyme with 'sky'. These discrepancies frequently occur and – as we noted early on – stem from the way in which Early Modern English was pronounced differently to our English today, and also how Shakespeare's Stratford accent influenced his composition. |

|

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

|

Then, when I have observed and considered all these matters, the idea or conception or thought of this short and unstable time we have on earth...

|

|

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight

|

...presents you on this stage in front of me in your full rich bloom of youth...

|

|

Where wasteful Time debateth with decay

|

...and here on this stage of the world is where the character of Time discusses with either the character of Decay or just internally with decay as a phenomenon...

|

|

To change your day of youth to sullied night;

|

...how to turn your bright glorious day of beautiful youth to the dark and sullied night of ultimate death.

"Sullied" has all kinds of connotations and in view of what has just gone before they are more than likely deliberate. It means 'soiled' and is still today as it was in the past used especially in the context of a person whose reputation is being besmirched which in turn often has direct or indirect sexual undertones. It is worth remembering though that night in Shakespeare's era for the vast majority of people and much of the time is a really glum period: there is no electricity, no gaslight. Candles, and fire and petroleum lamps have to be lit individually, they and their fuel are costly and for about half the year from the autumn equinox to the one in spring these nights are long and often bitterly cold. So it need not surprise us that Shakespeare variously thinks of night as 'black', 'hideous', 'ghastly' and here 'sullied'. |

|

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new. |

And as he, Time, takes your youth and your beauty away from you, much as discussed and planned and conspired with his accomplice or instrument decay, I, absorbed completely in a war with Time, give you new life by "engrafting" you.

The 'graft' takes us back to the analogy of the plants, where this is the technique by which you can give a plant a new branch and therefore lease of life. What Shakespeare means is that his pen, his writing, is rejuvenating the young man or indeed preserving his youth, that it is his, the poet's writing, that can conquer Time and decay. And we will look at this particular idea a bit more closely in just a moment because it is so striking. |

With the somewhat suggestive, slightly cheeky, and categorically confident Sonnet 15, William Shakespeare taps into a whole different register that positions him as the poet in a whole new relationship towards the young man he is writing to, and with astonishing effect.

We are nearing the end of the Procreation Sequence and it is not certain whether this is because something is changing between the poet and the young man, or whether it is in fact the other way round: the poet knows his task is effectively coming to an end and so he ups the ante once again. Some people would argue we don't even know whether the sonnets that follow the Procreation Sequence are addressed to the same young man, and we will discuss this question in a great deal more detail in a future episode. Whatever may be the case, what we get in Sonnet 15 is an amazing turn of events.

This is the second time in the series so far that a couple of sonnets are strung together to form one argument. Sonnet 15 does stand up on its own, but it really only sets out the situation as it currently stands with an ending that can, nevertheless, be accepted as the solution to the 'problem', wherein lies the exceptional audacity of this poem.

The situation as it stands is that everything in the world grows, reaches a highpoint and then from thereon in declines, racing toward death. This is not what makes Sonnet 15 revolutionary though. What does – at the very least within the course of poems Shakespeare is in the process of writing – is where he places himself in relation to the young man on the one hand and the tone he adopts on the other.

I regularly caution against 'reading too much into these sonnets', but there comes a point in every interpretation where it would seem churlish so as not to say idiotic to ignore the blatantly obvious. Shakespeare is being saucy. This is not in itself new or sensational, he is known from his plays to entertain his audience with bawdy jokes and innuendo when the opportunity offers itself, but this is the first time we hear it here in these sonnets, and the effect is certainly startling, especially because of the way this sonnet ends. It does not end with the by now more than just a tad familiar argument that the young man needs to make a child, it ends with me, the poet, William Shakespeare, declaring that I, in a war with Time for love of you, the young man, have the power to give you new life. That is the message of this sonnet on its own. Unless and until we get on to Sonnet 16, this is not a Procreation Sonnet at all, this is a sonnet in which a sonneteer is saying to the recipient of his words that it is these words, the writer's skill and devotion, that are by themselves capable of giving the young man a new lease of life when he needs it, which will be soon, because soon he will peak.

This opens up two highly contrasting and in unequal measure exhilarating possibilities: either William Shakespeare sets out from the start to write these two sonnets as a pair and really the conclusion of this one is a downbeat one that more than for a full stop asks for an ellipsis at the end: because I care for you, I am engaged in this struggle with time to help you beat the decay that befalls us all, but listen to what I have to say next, because clearly I am not going to get very far with this...

Or William Shakespeare effectively gives up on his task of convincing the young man of the need to get married and either deliberately or accidentally forgets what he is meant to be communicating to him and more or less offers an alternative, which is: I, with my writing, can make you stay young.

In view of what is soon to come – the ever more quickly approaching sensational Sonnet 18 – it is tempting to welcome the latter of these two explanations for Sonnet 15, but it may yet be hasty to do so. Also, we have no proof whatsoever that what is to come really was written after these sonnets that we have already listened to and looked at. But it is a distinct possibility and absolutely not one that we can simply dismiss. Nor, as it happens, can we dismiss a third possibility, which is that William Shakespeare knows full well what he is doing, which is writing a sonnet that sounds like it's temporarily given up on the idea of convincing the young man to get married and have children, but fully aware that this is after all still his task, he then backtracks swiftly to effectively save himself and in fact the young man any blushes.

Whichever way Shakespeare arrived at his tone for this Sonnet 15, it stands out. And – this once again may or may not be significant – it is the second sonnet in the sequence to employ the more formal address of 'you', which then continues into Sonnet 16. Now, previously when this happened, when Shakespeare switched from 'thou' to 'you', we aired the possibility that either consciously or subconsciously Shakespeare may be signalling that he is aware of his status in the world compared to that of the young man and softens or mediates his much more personal and intimate language by creating a greater distance with this higher level of formality. 'You' came into play when I, the poet, called the young man "love," and "dear my love" for the first time in Sonnet 13.

Here in Sonnet 15 I for the first time suggest that my writing could have a greater meaning for you than just telling you to do things: in Sonnet 15 on its own, I am saying that it is my writing that I produce "for love of you" that gives you new life, and the image I employ to do so is visceral, physical: "I engraft you new." There is an almost disturbing element of intimacy to this when imagined in relation to a person.

Listen to how the Wikipedia page on "grafting" describes the technique:

"Grafting or graftage is a horticultural technique whereby tissues of plants are joined so as to continue their growth together. The upper part of the combined plant is called the scion while the lower part is called the rootstock. The success of this joining requires that the vascular tissues grow together and such joining is called inosculation. The technique is most commonly used in asexual propagation of commercially grown plants for the horticultural and agricultural trades."

The word "graft" itself enters English via Old French and Latin from Greek graphein, which means 'to write'. We cannot reasonably doubt that Shakespeare knows this. Nor that he is in any way in the dark about how grafting works. What Shakespeare is telling the young man is that he and the young man, through his own writing can grow together and thus find a way of conquering everyone's common adversary, time. He offers, in effect, an alternative to sexual propagation.

Of course, the story of this sonnet doesn't end here, as it is quite inextricably linked to the one that follows, Sonnet 16...

We are nearing the end of the Procreation Sequence and it is not certain whether this is because something is changing between the poet and the young man, or whether it is in fact the other way round: the poet knows his task is effectively coming to an end and so he ups the ante once again. Some people would argue we don't even know whether the sonnets that follow the Procreation Sequence are addressed to the same young man, and we will discuss this question in a great deal more detail in a future episode. Whatever may be the case, what we get in Sonnet 15 is an amazing turn of events.

This is the second time in the series so far that a couple of sonnets are strung together to form one argument. Sonnet 15 does stand up on its own, but it really only sets out the situation as it currently stands with an ending that can, nevertheless, be accepted as the solution to the 'problem', wherein lies the exceptional audacity of this poem.

The situation as it stands is that everything in the world grows, reaches a highpoint and then from thereon in declines, racing toward death. This is not what makes Sonnet 15 revolutionary though. What does – at the very least within the course of poems Shakespeare is in the process of writing – is where he places himself in relation to the young man on the one hand and the tone he adopts on the other.

I regularly caution against 'reading too much into these sonnets', but there comes a point in every interpretation where it would seem churlish so as not to say idiotic to ignore the blatantly obvious. Shakespeare is being saucy. This is not in itself new or sensational, he is known from his plays to entertain his audience with bawdy jokes and innuendo when the opportunity offers itself, but this is the first time we hear it here in these sonnets, and the effect is certainly startling, especially because of the way this sonnet ends. It does not end with the by now more than just a tad familiar argument that the young man needs to make a child, it ends with me, the poet, William Shakespeare, declaring that I, in a war with Time for love of you, the young man, have the power to give you new life. That is the message of this sonnet on its own. Unless and until we get on to Sonnet 16, this is not a Procreation Sonnet at all, this is a sonnet in which a sonneteer is saying to the recipient of his words that it is these words, the writer's skill and devotion, that are by themselves capable of giving the young man a new lease of life when he needs it, which will be soon, because soon he will peak.

This opens up two highly contrasting and in unequal measure exhilarating possibilities: either William Shakespeare sets out from the start to write these two sonnets as a pair and really the conclusion of this one is a downbeat one that more than for a full stop asks for an ellipsis at the end: because I care for you, I am engaged in this struggle with time to help you beat the decay that befalls us all, but listen to what I have to say next, because clearly I am not going to get very far with this...

Or William Shakespeare effectively gives up on his task of convincing the young man of the need to get married and either deliberately or accidentally forgets what he is meant to be communicating to him and more or less offers an alternative, which is: I, with my writing, can make you stay young.

In view of what is soon to come – the ever more quickly approaching sensational Sonnet 18 – it is tempting to welcome the latter of these two explanations for Sonnet 15, but it may yet be hasty to do so. Also, we have no proof whatsoever that what is to come really was written after these sonnets that we have already listened to and looked at. But it is a distinct possibility and absolutely not one that we can simply dismiss. Nor, as it happens, can we dismiss a third possibility, which is that William Shakespeare knows full well what he is doing, which is writing a sonnet that sounds like it's temporarily given up on the idea of convincing the young man to get married and have children, but fully aware that this is after all still his task, he then backtracks swiftly to effectively save himself and in fact the young man any blushes.

Whichever way Shakespeare arrived at his tone for this Sonnet 15, it stands out. And – this once again may or may not be significant – it is the second sonnet in the sequence to employ the more formal address of 'you', which then continues into Sonnet 16. Now, previously when this happened, when Shakespeare switched from 'thou' to 'you', we aired the possibility that either consciously or subconsciously Shakespeare may be signalling that he is aware of his status in the world compared to that of the young man and softens or mediates his much more personal and intimate language by creating a greater distance with this higher level of formality. 'You' came into play when I, the poet, called the young man "love," and "dear my love" for the first time in Sonnet 13.

Here in Sonnet 15 I for the first time suggest that my writing could have a greater meaning for you than just telling you to do things: in Sonnet 15 on its own, I am saying that it is my writing that I produce "for love of you" that gives you new life, and the image I employ to do so is visceral, physical: "I engraft you new." There is an almost disturbing element of intimacy to this when imagined in relation to a person.

Listen to how the Wikipedia page on "grafting" describes the technique:

"Grafting or graftage is a horticultural technique whereby tissues of plants are joined so as to continue their growth together. The upper part of the combined plant is called the scion while the lower part is called the rootstock. The success of this joining requires that the vascular tissues grow together and such joining is called inosculation. The technique is most commonly used in asexual propagation of commercially grown plants for the horticultural and agricultural trades."

The word "graft" itself enters English via Old French and Latin from Greek graphein, which means 'to write'. We cannot reasonably doubt that Shakespeare knows this. Nor that he is in any way in the dark about how grafting works. What Shakespeare is telling the young man is that he and the young man, through his own writing can grow together and thus find a way of conquering everyone's common adversary, time. He offers, in effect, an alternative to sexual propagation.

Of course, the story of this sonnet doesn't end here, as it is quite inextricably linked to the one that follows, Sonnet 16...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!