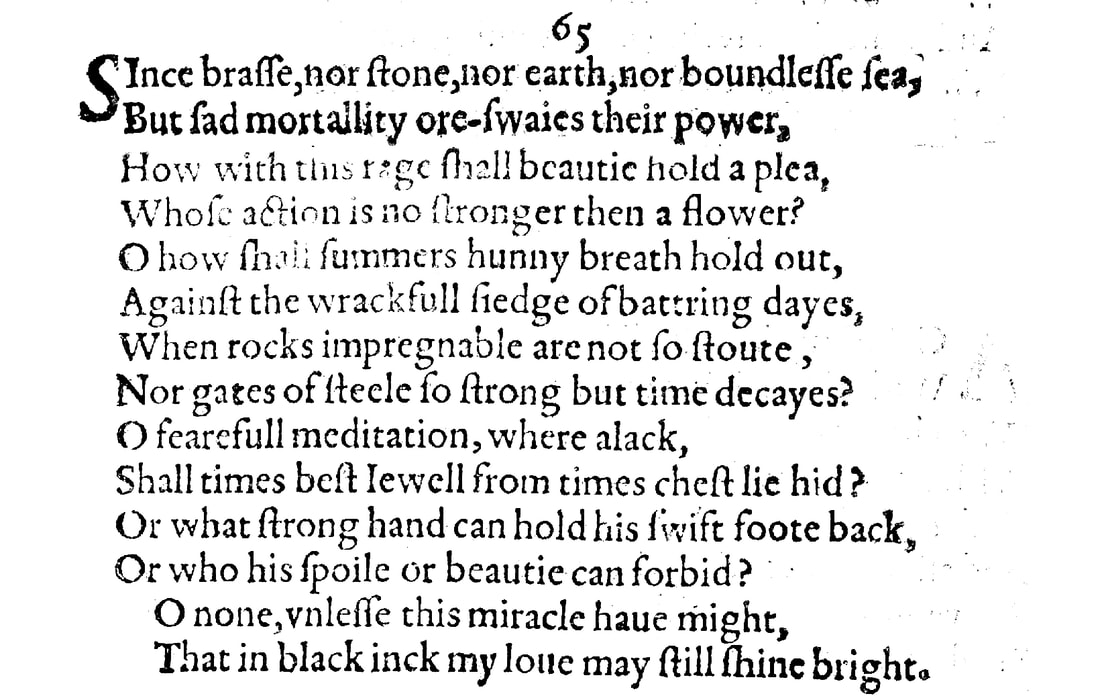

Sonnet 65: Since Brass, Nor Stone, Nor Earth, Nor Boundless Sea

|

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea

But sad mortality oresways their power, How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea, Whose action is no stronger than a flower? O how shall summer's honey breath hold out Against the wrackful siege of battering days, When rocks impregnable are not so stout, Nor gates of steel so strong, but time decays? O fearful meditation: where alack Shall time's best jewel from time's chest lie hid, Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back, Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid? O none, unless this miracle have might, That in black ink my love may still shine bright. |

|

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth nor boundless sea

But sad mortality oresways their power, |

Seeing that there is nothing – not brass, nor stone, nor the earth, nor the boundless sea – which is not ultimately overpowered by mortality, which in itself is inherently sad, of course, but also grave and in character the opposite of joyous and giddy or imbued with boisterous energy, the way lively nativity comes along in the form of a newborn or very young child...

'Oversway' is still recognised today as a legal term meaning "to hold sway over: to rule over," whereby its more general reading, "to have the upper hand over: to prevail over," is, in Merriam-Webster's definition, given as 'obsolete'. This courtroom metaphor continues: |

|

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea

Whose action is no stronger than a flower? |

...how then should beauty enter a 'plea' in this imaginary hearing and make a case for itself to overcome or withstand the rage, the angry and forever destructive force that is death, when its own, beauty's, 'action', for which here therefore read either specifically power in legal proceedings or more generally active force or strength to overcome adversity, is no greater than that of a flower?

The whole opening quatrain of this sonnet asks one simple question: if even the strongest and supposedly most durable materials are subject to the overwhelming force of decay and the finality of death, then how can beauty, which is understood to be lithe, and tender, and gentle, and subtle, and therefore, in that sense, weak, even stand a chance to live on, to conquer death? |

|

O how shall summer's honey breath hold out

Against the wrackful siege of battering days, |

The second quatrain asks exactly the same question again, now introducing a slightly half-hearted metaphor of weather and mixing it boldly with that of military equipment:

Oh how shall the sweet breath of summer – meaning the loveliness and beauty of a summer's day, just as evoked and then found wanting in Sonnet 18 – hold out or stand up against the destructive siege that is laid on it by the days that batter against it like storm and rain, with the force of an ancient weapon ramming a fortress or a city wall until it finally gives and crumbles... |

|

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but time decays? |

...when even rocks, which at first glance appear to be impregnable by water and immune to erosion turn out not to be so, because they will ultimately be hollowed out or broken down by these unrelenting forces, and even gates that are made of steel are not so strong that they would not over time fall apart.

'Impregnable' is used by Shakespeare elsewhere to mean 'invincible', which underlines the aspect of warfare between time and virtually everything else, much as we saw it also in Sonnet 2, where forty winters "besiege thy brow | And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field." |

|

O fearful meditation: where alack

Shall time's best jewel from time's chest lie hid, |

What a horrendous, terrible, indeed frightening, thought: where, alas, should the most precious thing that time has ever produced and lent to the world, namely beauty, which obviously stands here for the beautiful lover, be hidden from 'time's chest', which is the jewellery box or safe or treasure chest into which time will return everything that it ever lends when it takes this back.

A chest or box whose treasure in time is a beautiful young man, also strongly invokes a coffin into which he will one day be laid, and John Kerrigan in the New Penguin Shakespeare points out that the line compares "interestingly," as he calls it, to Sonnet 52: So is the time that keeps you as my chest Or as the wardrobe which the robe doth hide To make some special instant special blest By new unfolding his imprisoned pride. Whereby we cannot know, of course, whether this reference is intentional or not. |

|

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid? |

What strong hand is there in the world that can hold back the swift foot of time, or who is there that can forbid him, time, to spoil beauty by turning it old and wearing it out?

|

|

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright. |

There is none. Unless this miracle that I am trying to bring about right here and right now proves to have power and actually works, namely that in this black ink which I use to write my poem my lover may still shine bright and be thus kept alive in the minds of future generations.

Generally, it is accepted that 'love' here in the last line stands for 'lover', not least because the sonnet comes hard on the heels of Sonnet 63 which opens with the lines: Against my love shall be as I am now, With time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn Where that is unambiguously the case, with Sonnet 64 providing a strong thematic bridge to Sonnet 65. But it is true that, as Colin Burrow in The Oxford Shakespeare highlights, a layered meaning of 'my affection' cannot be ruled out and may in fact be entirely intentional, and clearly if – as hitherto has been the case – the miracle does work, and the young lover shines bright in these lines well over 400 years after they were composed, then so indeed does William Shakespeare's love for him. |

Sonnet 65 brings to a close – at least for the moment – this reflection on the passing of time that started with Sonnet 60 and focused quite heavily – certainly in parts – on William Shakespeare's preoccupation with his own age and mortality. The sonnet effectively provides a summing up of the arguments laid out over the previous four or five poems – strictly speaking, Sonnet 61 thematically does not entirely fit into this group – and in doing so it paves the way for a new wave of strongly felt emotions. The sonnet therefore, although it can stand on its own, should really be viewed in the context of these other time-related sonnets and be seen as the conclusion of a consideration that forms a fairly self-contained sequence in its own right.

With Sonnet 65 being relatively easy to understand and its contents covering well trodden ground in a familiar way, and with it taking up this position of rounding off a reflection on self and time in the context of a lover who is not only younger but also nowhere near as committed to this relationship as William Shakespeare, the poem affords us the opportunity to look at this short group it is part of as a whole to get a proper feel for our poet's predicament:

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end:

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

Crooked eclipses gainst his glory fight,

And time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands, but for his scythe to mow.

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising your worth, despite his cruel hand.

Is it thy will thy image should keep open

My heavy eyelids to the weary night?

Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken

While shadows like to thee do mock my sight?

Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee

So far from home into my deeds to pry

To find out shames and idle hours in me,

The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

O no, thy love, though much, is not so great:

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat

To play the watchman ever for thy sake.

For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere,

From me far off, with others all too near.

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account,

And for myself mine own worth do define

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me my self indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read:

Self so self-loving were iniquity.

Tis thee, my self, that for myself I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

Against my love shall be as I am now,

With time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn,

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn

Hath travelled on to age's steepy night,

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring;

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding age's cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life.

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age;

When sometime lofty towers I see downrazed

And brass eternal slave to mortal rage;

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

Increasing store with loss and loss with store;

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate:

That time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have that which it fears to lose.

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea

But sad mortality oresways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer's honey breath hold out

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but time decays?

O fearful meditation: where alack

Shall time's best jewel from time's chest lie hid,

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Hearing these sonnets like that, two contrasting senses vie for our attention: one of coherence and one of contradiction. Shakespeare seems torn by his feelings not just for his lover, but for himself, and in this oscillation between deep melancholy, even sadness, and a holding on to his capacity to give his young man and indeed his love for him lasting life a dynamic opens up which is nothing if not deeply troubled, but contained. The tone and therefore the mood of these sonnets sails close to, but doesn't quite give in to, despair, and nor do we sense any anger or bitterness. If anything there is a quiet and perhaps somewhat bewildered resignation to things being as they are, which clearly does not inspire jubilation and great cheer: there is none of the energy, none of the joy of earlier sonnets, nor is there a display of clever compositional conceits, contrived to court admiration. These poems are not 'fun'. And they don't aim or pretend to be either, they are, as Shakespeare himself calls the last one of the group, 'fearful meditations'.

And so if we are to assume, as suggested by Frances Meres in 1598, that some of these sonnets are circulating among Shakespeare's 'private friends', then it is of course possible that that is true also of this particular batch. The reason this is an interesting thought to entertain is that the poems we just heard are now followed by a further group that first expresses largely forceful emotions of frustration, fury, and dissatisfaction with the word, then give vent to a strong criticism of the young lover himself, which is almost immediately recanted and relativised, followed by more pondering on death and posterity, taking us to the curiously eye-catching midpoint with Sonnet 77 which with its didactic tone is suddenly reminiscent again of the early Procreation Sonnets, and then, streching over several poems, an admission to the young man by Shakespeare that his poetry has gone stale and Shakespeare accepting, albeit in no small measure grudgingly, that there is at least one other poet on the scene, threatening to usurp Will's favoured place.

All of these 'developments', if we want to call them that, forever mindful not to impose a linearity on these sonnets that may or may not actually be there, may look strange and puzzling in isolation, but in context actually make sense: if there is a handsome but petulant and obviously wealthy and well-known young man, and there is a coterie of private friends who as part of their culture and regular pastime read and possibly write and recite poetry, and one of their number, the poet who has come from respectable but humble beginnings in the countryside, who has not been to university, who is not part of the aristocracy and who has for his early notable successes been publicly disparaged as effectively an imposter – we touched on this in the Episode on Sonnet 25 and we will get back to it in due course – and this poet's poetry has gone from celebrating the young man, often citing his worth and virtues, sometimes lamenting his absence from him, and during one short period admonishing and then forgiving him for his transgressive behaviour, to talking in deeply personal terms about his own midlife crisis, then it would not be in the least surprising if said young man started to find himself disenchanted and perhaps objecting to, maybe even embarrassed by, how other people might see and talk about his involvement with the poet, and therefore beginning to prefer the possibly lighter, less personal but more flattering poetry of somebody else.

We don't know. And we haven't even got there yet. In the sequence of sonnets as they were originally published, we are still in the build up to something of an emotional climax which is now just around the corner. But it will be helpful to bear all this in mind and to have given some thought, at least, to how these sonnets, even if they do not pair up with each other directly and do not form a strictly sequential narrative, group and cluster around themes and concerns, thoughts and considerations, that appear to impact upon and in some instances cause or trigger each other. In other words, it helps our understanding of William Shakespeare through his sonnets, if every so often we take a step back and look at the intermediate picture and how the sonnets do enmesh with each other to form a kaleidoscopic portrait of the poet and his lover, giving us at the very least a flavour of the different stages of their relationship.

That relationship, faced with some formidable challenges, is about to enter a deep and prolonged crisis from which it arguably never fully recovers, even though it is yet to formulate its most firm and also, as it happens, one of its most famous expressions of love. What comes next though is one of the most extraordinary poems in the entire canon to show us Shakespeare at the height of his outrage and at the end of his tether: Sonnet 66.

With Sonnet 65 being relatively easy to understand and its contents covering well trodden ground in a familiar way, and with it taking up this position of rounding off a reflection on self and time in the context of a lover who is not only younger but also nowhere near as committed to this relationship as William Shakespeare, the poem affords us the opportunity to look at this short group it is part of as a whole to get a proper feel for our poet's predicament:

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end:

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

Crooked eclipses gainst his glory fight,

And time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands, but for his scythe to mow.

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising your worth, despite his cruel hand.

Is it thy will thy image should keep open

My heavy eyelids to the weary night?

Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken

While shadows like to thee do mock my sight?

Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee

So far from home into my deeds to pry

To find out shames and idle hours in me,

The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

O no, thy love, though much, is not so great:

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat

To play the watchman ever for thy sake.

For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere,

From me far off, with others all too near.

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account,

And for myself mine own worth do define

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me my self indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read:

Self so self-loving were iniquity.

Tis thee, my self, that for myself I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

Against my love shall be as I am now,

With time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn,

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn

Hath travelled on to age's steepy night,

And all those beauties whereof now he's king

Are vanishing or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring;

For such a time do I now fortify

Against confounding age's cruel knife,

That he shall never cut from memory

My sweet love's beauty, though my lover's life.

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them still green.

When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age;

When sometime lofty towers I see downrazed

And brass eternal slave to mortal rage;

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

Increasing store with loss and loss with store;

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate:

That time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have that which it fears to lose.

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea

But sad mortality oresways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer's honey breath hold out

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but time decays?

O fearful meditation: where alack

Shall time's best jewel from time's chest lie hid,

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Hearing these sonnets like that, two contrasting senses vie for our attention: one of coherence and one of contradiction. Shakespeare seems torn by his feelings not just for his lover, but for himself, and in this oscillation between deep melancholy, even sadness, and a holding on to his capacity to give his young man and indeed his love for him lasting life a dynamic opens up which is nothing if not deeply troubled, but contained. The tone and therefore the mood of these sonnets sails close to, but doesn't quite give in to, despair, and nor do we sense any anger or bitterness. If anything there is a quiet and perhaps somewhat bewildered resignation to things being as they are, which clearly does not inspire jubilation and great cheer: there is none of the energy, none of the joy of earlier sonnets, nor is there a display of clever compositional conceits, contrived to court admiration. These poems are not 'fun'. And they don't aim or pretend to be either, they are, as Shakespeare himself calls the last one of the group, 'fearful meditations'.

And so if we are to assume, as suggested by Frances Meres in 1598, that some of these sonnets are circulating among Shakespeare's 'private friends', then it is of course possible that that is true also of this particular batch. The reason this is an interesting thought to entertain is that the poems we just heard are now followed by a further group that first expresses largely forceful emotions of frustration, fury, and dissatisfaction with the word, then give vent to a strong criticism of the young lover himself, which is almost immediately recanted and relativised, followed by more pondering on death and posterity, taking us to the curiously eye-catching midpoint with Sonnet 77 which with its didactic tone is suddenly reminiscent again of the early Procreation Sonnets, and then, streching over several poems, an admission to the young man by Shakespeare that his poetry has gone stale and Shakespeare accepting, albeit in no small measure grudgingly, that there is at least one other poet on the scene, threatening to usurp Will's favoured place.

All of these 'developments', if we want to call them that, forever mindful not to impose a linearity on these sonnets that may or may not actually be there, may look strange and puzzling in isolation, but in context actually make sense: if there is a handsome but petulant and obviously wealthy and well-known young man, and there is a coterie of private friends who as part of their culture and regular pastime read and possibly write and recite poetry, and one of their number, the poet who has come from respectable but humble beginnings in the countryside, who has not been to university, who is not part of the aristocracy and who has for his early notable successes been publicly disparaged as effectively an imposter – we touched on this in the Episode on Sonnet 25 and we will get back to it in due course – and this poet's poetry has gone from celebrating the young man, often citing his worth and virtues, sometimes lamenting his absence from him, and during one short period admonishing and then forgiving him for his transgressive behaviour, to talking in deeply personal terms about his own midlife crisis, then it would not be in the least surprising if said young man started to find himself disenchanted and perhaps objecting to, maybe even embarrassed by, how other people might see and talk about his involvement with the poet, and therefore beginning to prefer the possibly lighter, less personal but more flattering poetry of somebody else.

We don't know. And we haven't even got there yet. In the sequence of sonnets as they were originally published, we are still in the build up to something of an emotional climax which is now just around the corner. But it will be helpful to bear all this in mind and to have given some thought, at least, to how these sonnets, even if they do not pair up with each other directly and do not form a strictly sequential narrative, group and cluster around themes and concerns, thoughts and considerations, that appear to impact upon and in some instances cause or trigger each other. In other words, it helps our understanding of William Shakespeare through his sonnets, if every so often we take a step back and look at the intermediate picture and how the sonnets do enmesh with each other to form a kaleidoscopic portrait of the poet and his lover, giving us at the very least a flavour of the different stages of their relationship.

That relationship, faced with some formidable challenges, is about to enter a deep and prolonged crisis from which it arguably never fully recovers, even though it is yet to formulate its most firm and also, as it happens, one of its most famous expressions of love. What comes next though is one of the most extraordinary poems in the entire canon to show us Shakespeare at the height of his outrage and at the end of his tether: Sonnet 66.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!