Sonnet 1: From Fairest Creatures We Desire Increase

|

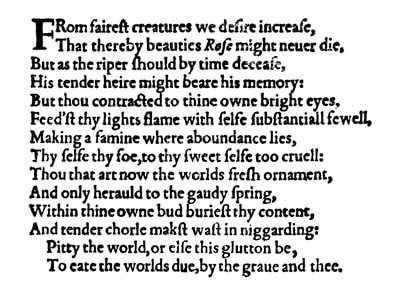

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die, But, as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory. But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes, Feedst thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel, Making a famine where abundance lies: Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel: Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament, And only herald to the gaudy spring, Within thine own bud buriest thy content And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding. Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee. |

|

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

|

From the most beautiful beings – quite generally – we wish that they multiply; we want more of them. The implication here of course is that the person who is being addressed is one of these 'fairest creatures'.

|

|

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

|

So that the flower of beauty and thus beauty itself may go on living.

The rose is a heavily symbolic flower in Elizabethan England of, among other things, beauty, and it is interesting to note that in the first published Quarto Edition, the word is capitalised and put in italics. While this may be of some significance, it is worth pointing out this early on that spelling and grammar are something of a free-for-all in Shakespeare's day. He himself uses many different spellings of individual words, and typesetting was often haphazard and down to the printer's or typesetter's quirks, sometimes as basic as what physical letters were available to them at the time. Almost all the textual difficulties that these sonnets present stem from such inconsistencies and from obvious printing and typesetting errors. This is also where the majority of the variations between different editions of the sonnets stem from. |

|

But, as the riper should by time decease,

|

But, as the older person – here by implication the father of the heir mentioned in the next line – eventually dies...

|

|

His tender heir might bear his memory.

|

...his child will remind the world of his father by 'bearing his memory': the son is expected to resemble his father and carry on his beauty.

In this line it is also made clear that we are talking about a man and his heir: a father and his son. |

|

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

|

But you, who are beholden to your own beauty – the suggestion here is that the young man is somewhat in love with himself and showing some fairly narcissistic tendencies...

|

|

Feedst thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

|

...you burn with love of and for yourself.

Later on we hear how Shakespeare admonishes the young man by saying, thou "consumest thyself". This is quite similar: the young man is told that he is burning himself up with his love for himself, thus depriving the world of his beauty, as it will invariably perish with him when he dies. |

|

Making a famine where abundance lies,

|

By feeding on yourself, you take that beauty which you have in abundance and use it on yourself.

The implication is that because you don't produce any offspring – which is only possible by devoting yourself to someone other than yourself – your beauty, which you have in abundance, instead of being perpetuated, is simply used up. |

|

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

|

In doing so, you become your own enemy; you are being cruel to yourself.

|

|

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament

|

You, who are now, on account of your youth and beauty, the ornament or adornment of the world...

|

|

And only herald to the gaudy spring

|

...and who therefore 'heralds' – which here really means 'represents' – spring; spring being youth, fertility, lushness, abundance, ('gaudy' does not have any negative connotation of garishness here, as it would in contemporary English; it is more simply colourful and bright)...

|

|

Within thine own bud buriest thy content

|

...put yourself into yourself.

This may be somewhat sexually suggestive here, but the main point is that you can only create an heir if you pollinate another flower, not yourself. The young man is admonished for not doing so. PRONUNCIATION: Note that buriest here has two syllables: bu-ri'st. |

|

And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding.

|

And you are being wasteful in being miserly. 'Tender churl' is a typically Shakespearean way of addressing the young man in contradictory terms. A 'churl' is a rude, mean-spirited person, but the 'tender' softens this and makes it sound gently ironic.

'Niggarding' simply means being miserly. As a word in the English language it dates back to the 14th century and has nothing to do with the racial slur that it might be confused with, which was coined much later. |

|

Pity the world, or else this glutton be

|

Have pity on the world, or else you will be and be considered a glutton, somebody who greedily and selfishly feeds himself...

|

|

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

|

...by eating yourself up and thus taking yourself and all your beauty, which belongs to the world, to the grave with you when you die.

|

Sonnet 1 is the first sonnet in the originally published canon, and it marks the first of what are known as the Fair Youth Sonnets and also the first of the Procreation Sonnets which are part of the Fair Youth Sonnets, consisting of the first seventeen sonnets that are addressed to a young man.

As explained in the Introduction, we cannot know whether this is the first sonnet that Shakespeare wrote, and in fact recent research and analysis of his use of vocabulary suggests that it most likely isn't. What we do know is that the first Quarto Edition of 1609 puts this sonnet first and gives it the number 1, and we also know that Shakespeare was alive in 1609, and while we cannot know whether Shakespeare authorised or let alone prepared this edition, we also have no record of his challenging or contesting it at the time.

Our approach with SONNETCAST is to go by what we know and have, and what we know and have are the words as they were originally published, and so we will treat this as the beginning of our exploration.

In Sonnet 1, William Shakespeare – for reasons we do not know – tells a young man – of whom we don't know yet and will never know for absolutely certain who he is – that he is being miserly and selfish by not sharing his beauty with the world. He gently admonishes him for being somewhat obsessed with himself and implores him to take pity on the world and give of himself by producing an heir who will then be able to remind the world of his beauty by continuing to live even after he himself has died.

The sonnet thus sets the tone and the theme for the Procreation Sonnets, as they are all concerned with this particular aim: to convince the young man that it is now time to marry and have children, with the express purpose of producing an heir. This, in Shakespeare's day by necessity means a son.

Going by Sonnet 1 alone this is more or less all we know so far: the poet, William Shakespeare, is telling a young man of unnamed identity that he is wasting his beauty on himself and depriving the world of its due by not having children, and asks him to change his ways.

The two most immediate questions that present themselves are of course: who? and why? Who is this young man, and why is Shakespeare at all concerned with the perpetuation of his lineage? The sonnet does not answer these questions and so it will be part of our journey of exploration to look out for clues, of which, thankfully, there will be quite a few...

As explained in the Introduction, we cannot know whether this is the first sonnet that Shakespeare wrote, and in fact recent research and analysis of his use of vocabulary suggests that it most likely isn't. What we do know is that the first Quarto Edition of 1609 puts this sonnet first and gives it the number 1, and we also know that Shakespeare was alive in 1609, and while we cannot know whether Shakespeare authorised or let alone prepared this edition, we also have no record of his challenging or contesting it at the time.

Our approach with SONNETCAST is to go by what we know and have, and what we know and have are the words as they were originally published, and so we will treat this as the beginning of our exploration.

In Sonnet 1, William Shakespeare – for reasons we do not know – tells a young man – of whom we don't know yet and will never know for absolutely certain who he is – that he is being miserly and selfish by not sharing his beauty with the world. He gently admonishes him for being somewhat obsessed with himself and implores him to take pity on the world and give of himself by producing an heir who will then be able to remind the world of his beauty by continuing to live even after he himself has died.

The sonnet thus sets the tone and the theme for the Procreation Sonnets, as they are all concerned with this particular aim: to convince the young man that it is now time to marry and have children, with the express purpose of producing an heir. This, in Shakespeare's day by necessity means a son.

Going by Sonnet 1 alone this is more or less all we know so far: the poet, William Shakespeare, is telling a young man of unnamed identity that he is wasting his beauty on himself and depriving the world of its due by not having children, and asks him to change his ways.

The two most immediate questions that present themselves are of course: who? and why? Who is this young man, and why is Shakespeare at all concerned with the perpetuation of his lineage? The sonnet does not answer these questions and so it will be part of our journey of exploration to look out for clues, of which, thankfully, there will be quite a few...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!