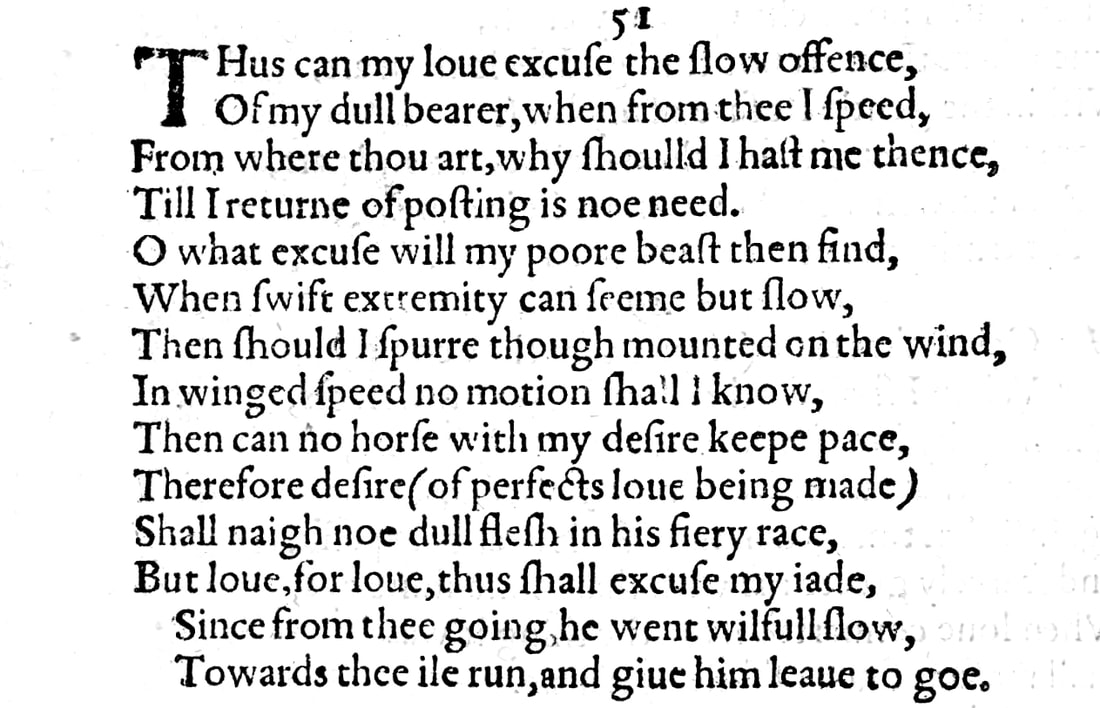

Sonnet 51: Thus Can My Love Excuse the Slow Offence

|

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed: From where thou art, why should I haste me thence? Till I return, of posting is no need. O what excuse will my poor beast then find, When swift extremity can seem but slow? Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind, In winged speed no motion shall I know. Then can no horse with my desire keep pace, Therefore desire, of perfectst love being made, Shall neigh, no dull flesh in his fiery race, But love for love thus shall excuse my jade: Since from thee going he went wilful slow, Towards thee I'll run, and give him leave to go. |

|

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed: |

The poem continues from Sonnet 50:

In the following way the love that I feel for you can help or make me forgive the offensive slowness of my sluggish horse when I travel away from you: The verb 'speed' here is surprising, because the entire 'story' of the previous poem and indeed the 'slow offence' cited is caused by the horse not going as fast as he should. Most likely the contrast is intended to set up the juxtapositions that follow and to highlight the fact that no matter how slowly the horse carries me, as long as he carries me away from you, it will always be too fast. |

|

From where thou art, why should I haste me thence?

Till I return, of posting is no need. |

Why should I hurry away from where you are? Until I return to you there is no need for speed.

'Posting' here has the archaic meaning to 'travel with haste; hurry', and we still have 'post-haste' to mean 'with great speed'. (Oxford Dictionaries) The excuse, in other words, that the poet's love for his young man finds to forgive his horse is simply that moving away from him, there is no rush. And indeed, in Sonnet 50, he told us that the horse seems to know this instinctively. |

|

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow? |

But then, when I return to you, what excuse will my poor horse find for going slowly, when the fastest mode of transport in the world can only seem slow to me?

This in my somewhat clumsy terms 'fastest mode of transport' is not specified here, but in an age before planes, trains, or automobiles, a swift extremity would be either a racehorse or a mythical or metaphorical carrier, as the following lines now get onto: |

|

Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind,

In winged speed no motion shall I know. |

Then – on my return to you – I would use my spurs even if I were riding on the wind itself, because even if I could fly back to you the speed with which I would be travelling would seem to me so slow as to appear motionless.

The comparison with the wind for speed is a commonplace to this day, as is the notion that flying through the air would get us there in no time. The use of the spur 'though mounted on the wind', meanwhile, is a particularly evocative image: in the previous sonnet "the bloody spur" could not "provoke" the horse on, and here now, on his return journey, Shakespeare would try to make the wind go faster because even flying through the air would feel like standing still to him, so keen is he to get back to his lover. Note of course that the word wingèd here is pronounced as two syllables. |

|

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

|

Then – on my return to you – no horse in the world can keep up with my desire for being with you, meaning no matter how fast it is, it will not be fast enough.

|

|

Therefore desire, of perfectst love being made,

Shall neigh, no dull flesh in his fiery race, |

And for this reason – because no horse could be fast enough for me – desire itself shall carry me, because desire has no physical substance, no dull flesh, that could slow it down in its fiery race towards you.

There is an echo here to the similarly themed Sonnet 44: If the Dull Substance of My Flesh Were Thought, where Shakespeare bemoans the fact that the heavy materiality of his body prevents him from being with his lover in an instant, in the way his thoughts can be. The Quarto Edition here has 'perfects' which is generally accepted to be a typesetting error, though editors make different choices to resolve it. Some argue that there cannot be a superlative for 'perfect', since 'perfect' is by definition unimprovable, and therefore emend to 'perfect', but Shakespeare is known to like his pointed word creations for poetic effect, whilst at the same time not being a man who is overly concerned with logic or grammar, and he uses 'perfectst' elsewhere, so I have here sided with those editors who emend to this. |

|

But love for love thus shall excuse my jade:

|

But my love for you, for the sake of love itself will now excuse my old and worn-out horse - my jade – in the following way:

|

|

Since from thee going he went wilful slow

Towards thee I'll run, and give him leave to go. |

Since travelling away from you he went wilfully slowly, on my way back to you I will run and give him permission to go at his own pace.

To 'give leave' appears frequently in Shakespeare, mostly to simply mean 'grant permission', and here in the context it acquires layered meanings, which are surely intended. To give someone leave to go means on the one hand to allow them to leave, to release them from their service, and in the context of a horse it can also infer that the horse is given free rein and thus permission to go at its own preferred speed. Such a 'free rein' would usually suggest a gallop, which would turn the old, worn-out nag or jade into a fast horse. Such a transformation seems unlikely though with an animal as described and it seems similarly implausible that Shakespeare wants to suggest – as could also be implied – that the horse, left to his own devices and without a rider, will simply retrace his steps back to the stable while the poet is literally running home. So Shakespeare may here simply be saying that the horse can do what he wants, my desire for you will carry me to you faster than he ever could anyway: it is another one of these cases where the poem doesn't quite stand up to logical analysis and scrutiny, but we certainly get the gist... |

Sonnet 51 picks up from the dull-paced journey of Sonnet 50 and contrasts this with the poet's boundless desire for speed once he is on the way back home to his lover. It also marks the end of the extended period of separation that began with Sonnet 43 and so concludes this sequence of nine sonnets that appear to have been written while Shakespeare is away from London.

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel's end,

Doth teach that ease and that repose to say:

'Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend'.

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe,

Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me,

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee.

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on

That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide,

Which heavily he answers with a groan,

More sharp to me than spurring to his side,

For that same groan doth put this in my mind:

My grief lies onward, and my joy behind.

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed:

From where thou art, why should I haste me thence?

Till I return, of posting is no need.

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow?

Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind,

In winged speed no motion shall I know.

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

Therefore desire, of perfectst love being made,

Shall neigh, no dull flesh in his fiery race,

But love for love thus shall excuse my jade:

Since from thee going he went wilful slow,

Towards thee I'll run, and give him leave to go.

Sonnet 51 offers a stark contrast to its counterpart Sonnet 50, not only in the modes of travel it describes and the aspired speed they entail, but also in its tonality, mood, and verbal pace. When Sonnet 50 conveys a mournful, downcast sorrow at both, having to travel and the resulting absence from my lover, settling into a slow, even sluggish rhythm, this poem almost doubles the pace:

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel's end...

Compare the five genuinely stressed syllables of the first two lines of Sonnet 50 with the eight in the opening two lines in Sonnet 51:

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer when from thee I speed:

And further down this is notched up yet again:

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

Wherefore desire, of perfectst love being made

This is not, of course, a rigid and exact analysis, since these emphases depend very much on the speaker and you can argue for fewer or more stresses in both instances, but a similar contrast also exists in the choice of vocabulary and even in the coherence of the two poems. Sonnet 50 speaks in completely naturalistic terms of the horse, his hide, the spur, and the blood the spur draws as the rider in his futile anger tries to make him go faster. There are no similes, no metaphors, nor hardly any other rhetorical devices, except perhaps for allowing 'that ease and that repose' to speak to the poet directly, as if they were persons.

Sonnet 51 speaks of being 'mounted on the wind', of 'winged speed', and then likens desire itself to a thoroughbred racehorse that neighs in 'his fiery race'. And while Sonnet 50 is so easy to understand and so earthy in its simple meaning that, though beautiful, it may almost be perceived to be a bit pedestrian, Sonnet 51 takes off into a realm of fancy where the thinking no longer strictly hangs together, but we are happy to make do with getting the general sense of what the excited poet is trying to say.

As a pair, Sonnets 50 & 51 yield no profound insights beyond opening this window into William Shakespeare's state of mind when away and his mode of transportation, but those two are in their own right of great value: they confirm with an unusual degree of certainty what we thought we could understand from some previous sonnets that marked most likely an earlier and shorter absence, and they add texture and colour to the outline picture we have been forming from Sonnets 27 and 28, for example.

What comes next though in the series are poems that amply reward our patience. Starting with Sonnet 52, a compelling sequence of sonnets awaits us that gives us a much deeper understanding of the nature of the relationship William Shakespeare is having with his young lover...

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel's end,

Doth teach that ease and that repose to say:

'Thus far the miles are measured from thy friend'.

The beast that bears me, tired with my woe,

Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me,

As if by some instinct the wretch did know

His rider loved not speed being made from thee.

The bloody spur cannot provoke him on

That sometimes anger thrusts into his hide,

Which heavily he answers with a groan,

More sharp to me than spurring to his side,

For that same groan doth put this in my mind:

My grief lies onward, and my joy behind.

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer, when from thee I speed:

From where thou art, why should I haste me thence?

Till I return, of posting is no need.

O what excuse will my poor beast then find,

When swift extremity can seem but slow?

Then should I spur, though mounted on the wind,

In winged speed no motion shall I know.

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

Therefore desire, of perfectst love being made,

Shall neigh, no dull flesh in his fiery race,

But love for love thus shall excuse my jade:

Since from thee going he went wilful slow,

Towards thee I'll run, and give him leave to go.

Sonnet 51 offers a stark contrast to its counterpart Sonnet 50, not only in the modes of travel it describes and the aspired speed they entail, but also in its tonality, mood, and verbal pace. When Sonnet 50 conveys a mournful, downcast sorrow at both, having to travel and the resulting absence from my lover, settling into a slow, even sluggish rhythm, this poem almost doubles the pace:

How heavy do I journey on the way,

When what I seek, my weary travel's end...

Compare the five genuinely stressed syllables of the first two lines of Sonnet 50 with the eight in the opening two lines in Sonnet 51:

Thus can my love excuse the slow offence

Of my dull bearer when from thee I speed:

And further down this is notched up yet again:

Then can no horse with my desire keep pace,

Wherefore desire, of perfectst love being made

This is not, of course, a rigid and exact analysis, since these emphases depend very much on the speaker and you can argue for fewer or more stresses in both instances, but a similar contrast also exists in the choice of vocabulary and even in the coherence of the two poems. Sonnet 50 speaks in completely naturalistic terms of the horse, his hide, the spur, and the blood the spur draws as the rider in his futile anger tries to make him go faster. There are no similes, no metaphors, nor hardly any other rhetorical devices, except perhaps for allowing 'that ease and that repose' to speak to the poet directly, as if they were persons.

Sonnet 51 speaks of being 'mounted on the wind', of 'winged speed', and then likens desire itself to a thoroughbred racehorse that neighs in 'his fiery race'. And while Sonnet 50 is so easy to understand and so earthy in its simple meaning that, though beautiful, it may almost be perceived to be a bit pedestrian, Sonnet 51 takes off into a realm of fancy where the thinking no longer strictly hangs together, but we are happy to make do with getting the general sense of what the excited poet is trying to say.

As a pair, Sonnets 50 & 51 yield no profound insights beyond opening this window into William Shakespeare's state of mind when away and his mode of transportation, but those two are in their own right of great value: they confirm with an unusual degree of certainty what we thought we could understand from some previous sonnets that marked most likely an earlier and shorter absence, and they add texture and colour to the outline picture we have been forming from Sonnets 27 and 28, for example.

What comes next though in the series are poems that amply reward our patience. Starting with Sonnet 52, a compelling sequence of sonnets awaits us that gives us a much deeper understanding of the nature of the relationship William Shakespeare is having with his young lover...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!