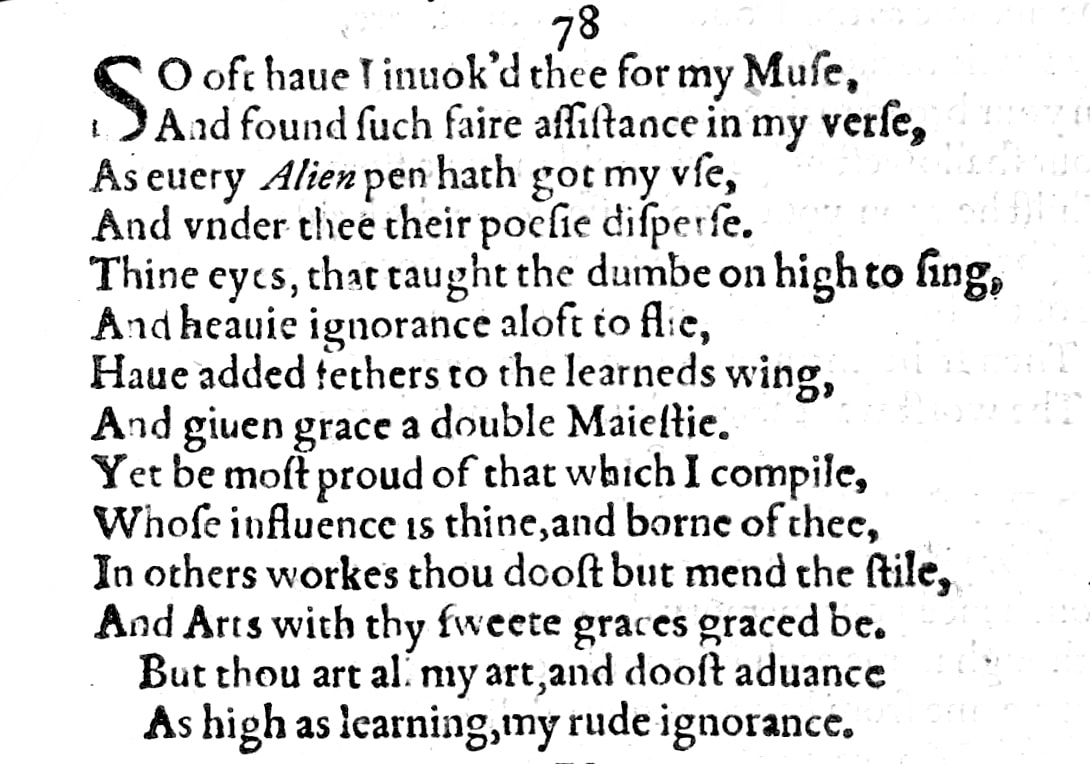

Sonnet 78: So Oft Have I Invoked Thee for My Muse

|

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse

And found such fair assistance in my verse, As every alien pen hath got my use And under thee their poesy disperse. Thine eyes that taught the dumb on high to sing And heavy ignorance aloft to fly Have added feathers to the learned's wing And given grace a double majesty. Yet be most proud of that which I compile Whose influence is thine and borne of thee: In others' works thou dost but mend the style And arts with thy sweet graces graced be. But thou art all my art and dost advance As high as learning my rude ignorance. |

|

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse

And found such fair assistance in my verse |

So often have I drawn on you for inspiration and written poetry to and for you, and in doing so I have found such 'beautiful' help in my writing through and from you...

The idea that a lover is a poet's muse is, of course, well established in the tradition of poetry, and in fact William Shakespeare in Sonnet 38 went one step further than simply calling his young man his muse by saying to him: Be thou the tenth Muse, ten times more in worth Than those old nine which rhymers invocate, And he that calls on thee, let him bring forth Eternal numbers to outlive long date. Here Shakespeare picks up on this thought by effectively saying that that is exactly what he himself has been doing, invoking him in endless numbers of poems, though whether or not he consciously means to reference his Sonnet 38 here, we cannot tell. A strong echo certainly reverberates from the very recent Sonnet 76, in which Shakespeare observes that he keeps writing the same thing over and over again, and so this Sonnet confirms what Sonnet 76 very strongly suggested: that Shakespeare is writing to the same young man over an extended period, producing many, many sonnets for him and not much, if anything, for anybody else at this point. The 'fair assistance', meanwhile, lends the line multiple layers of meaning. On the one hand it refers to the young man himself, of course, because he is, and has often been described now as, 'fair', meaning 'beautiful', and so any assistance coming from him would by necessity be infused by the quality of beauty. On the other hand, the fair can also be read as applying to the result of the assistance, which would make it a little more conceited, as Shakespeare would be saying his poetry is beautiful, but he could be allowed this and forgiven for it because the beauty of his writing is credited entirely to its inspiration, which stems from the young man And the choice of 'assistance' also allows for the possibility that the inspiration that Shakespeare receives from the young man is augmented by material, as in financial, support. This is a dimension that shines through very occasionally in these sonnets, and it would not be in the least unusual for a poet to enjoy the patronage of a young nobleman such as this lover of Shakespeare's most likely is, but we have no concrete proof of it being the case. |

|

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse. |

I have done this so much and have had such help from you ...that now every other poet has adopted my practice and started doing what I do, which is to write poetry for and dedicated to you.

This is likely to be something of an exaggeration on Shakespeare's part. The poems that follow in this group point much more towards one other poet making his presence felt, but it is nothing if not a human response: if you feel undermined in your standing and jealous about somebody else, you may well find yourself saying something like: oh, so everybody else is now doing podcasts on Shakespeare's sonnets, are they? Although fortunately this is, for the time-being, as far as I know, a purely hypothetical analogy... Editors note that the use of 'alien' here to mean 'other' is so unusual as to merit calling it singular, while 'pen' is a simple case of metonymy, the rhetorical device whereby one word, here 'pen' stands in for another that is closely associated with it, here 'poet'. |

|

Thine eyes that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly |

Your eyes, which through their beauty have taught me, who I was dumb with ignorance before – meaning I had no voice, no knowledge, and no skill, I was unable to express myself before you came into my life – to sing out loud and strong and also in elevated, even exalted tones and to soar in my expressive powers...

This is not the first time that Shakespeare disparages himself in what appears to be a modesty that, if it is not exactly false, then does come across as not entirely sincere. This, in combination with the following couple of lines, positions the poet in contrast to the 'learned' people around him, and we get a sense here that Shakespeare resents being regarded as untutored or unlearned. Sonnet 71 urged the young man to forget about his poet and not mourn him after his death, Lest the wise world should look into your moan And mock you with me after I am gone. And we noted at the time that of course Shakespeare was publicly mocked by Robert Greene – who was part of the university-educated 'wits' – with his famous 'upstart crow' slur. A minor, but possibly fascinating detail. Shakespeare talks a lot about eyes. This is hardly surprising, the eyes are seen as windows to the soul, and in a world where people look at each other and into each other's eyes, not least they have little else to look at by comparison, certainly to us, with our visual over-stimulation, they matter a great deal. He uses 'eye', 'eyes', and 'eyed' no less than 1339 times in his complete works. And in the Fair Youth sonnets he repeatedly makes a point of telling the young man how beautiful his eyes are. This is not something that reveals anything totally out of the ordinary to us, since marvelling at a lover's eyes is after all a poetic commonplace, but it is still interesting to note that here it is once again, one might say, the eyes that have a special effect on Shakespeare. |

|

Have added feathers to the learned's wing

And given grace a double majesty. |

...those same eyes that have thus elevated me have also added feathers to the wings of the learned poets, making them soar even higher, and they have equipped grace with a second layer of majesty.

Editors are of a mind that "added feathers to the learned's wing" is a reference to falconry, where the damaged wings of falcons would be 'imped' with additional feathers to restore their strength, or indeed more feathers would be added to the falcons' healthy plumage to augment their performance. And there is, of course, almost certainly a strong pun intended on 'feather' as in 'quill', since poets in Shakespeare's day used actual bird feathers to write with. The Quarto Edition has no apostrophe with 'learned's' which allows for this to be read as a plural or a singular. In our grammar, depending on which it is, we would place the apostrophe either after the d or after the s, and most editors seem to prefer the former, and 'wing' being in the singular does make this an easier construction to defend. The idea of 'grace' being given a 'double majesty' is especially intriguing and possibly telling. We have speculated before – and we will do so again at length when we come to discuss him in detail – that Shakespeare's young lover is an aristocrat, a young nobleman. Several hints at this have been spotted, though – as is the case here – it can't be said with certainty whether they were intentionally dropped or not. It is the case that 'Your Grace' would be the correct form of address for a Lord, and this line may therefore imply that the young man, with his patronage, attention, or purely by virtue of the fact that a poet is dedicating his work to him, lends majesty – worth, prestige, even glory – to the poet. This, if the poet himself is a member of the aristocracy, would then therefore be doubled. And although we can't be sure that that's what Shakespeare is doing here, it would fit with his contrasting of himself as the unlearned commoner – the country bumpkin, so to speak – against the educated urbane nobility that he is now competing against. |

|

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

|

But be most proud of that which I put together...

'Compile' has curious connotations. Its Latin source compilare means 'to plunder, plagiarise', and from about 1600 onwards the English definition would have been closer to 'to gather, to collect', but here Shakespeare clearly uses it to mean 'compose', unless of course he deliberately further diminishes his own contribution to his – or his rivals' to their – poetry by calling what he is doing, and thus by extension what they are doing, a gathering up and listing of the great qualities their muse, the young man, possesses. And the next Sonnet, Sonnet 79, will in fact point further towards this interpretation. |

|

Whose influence is thine and borne of thee,

|

...the inspiration for and therefore also impact of which is entirely yours, both in the sense that it belongs to you and also that it stems or flows from you. This emphasis on it being both 'thine' and 'borne of thee' also hints at there being an element of patronage and therefore ownership involved. In other words, it infuses the poem further with a sense of possession.

Editors also agree that 'influence' is used here in its astrological sense, in the way that stars were and still widely are believed to guide our actions, to determine our fates and our fortunes; a notion to which Shakespeare gives expression as early as Sonnet 15: When I consider every thing that grows Holds in perfection but a little moment, That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows, Whereon the stars in secret influence comment. |

|

In others' works thou dost but mend the style

|

In the work of other poets you only improve their style and therefore quality, as opposed to cause and inform the substance of what they are writing...

|

|

And arts with thy sweet graces graced be.

|

...and the skill and artistry of people who already know how to write and who are already educated and expert in their writing are merely given an additional touch of elegance, kudos, and again, significantly, grace – the veneer that comes with an association with nobility – by your attachment to them.

|

|

But thou art all my art and dost advance

As high as learning my rude ignorance. |

But for me, in contrast to them, you are all my skill, my artistry, meaning that you – as stated earlier on – make of me a person who can write to begin with, you are the cause and source of any knowledge or expertise that I have and you cultivate, elevate, and thus advance me in my rude – for which read untutored, uneducated, coarse – ignorance to a level that is as high as that of a learned person. The implication is a university educated person, someone with the kind of education Shakespeare's rivals and the coterie of 'wits' around the likes of Robert Greene would have been furnished with, in some cases possibly mostly owing to their privilege and status in society rather than to any innate talent or genius, we might conclude.

|

Sonnet 78 is the first in a group of nine sonnets that concern themselves almost entirely with the apparent arrival on the scene of someone else who is now writing poetry for Shakespeare's young lover, vying for his attention and possibly obtaining his patronage, which is why these poems are collectively known as the Rival Poet Sonnets. Strictly speaking, Sonnet 81 does not mention this rival and could therefore in theory be excluded from the group, but as it sits where it does and, like the others, talks about Shakespeare's own poetic powers, it is generally accepted as part of it.

Sonnet 78 also happens to mark the beginning of the second half of the collection of 154 sonnets originally published in 1609, and thus ushers in a major new phase in the numbered sequence, although whether or not this is deliberate, we cannot tell. What we do know from this sonnet and its companions is that here begins a whole new crisis for William Shakespeare, which will have a profound and lasting effect on him and his relationship with the young man.

At first glance, Sonnet 78, in its tone and its construction, strikes us as nothing so much as peeved. Shakespeare is saying to his young man: I compose all these beautiful, loving sonnets for you, and what happens? Everybody else jumps on the bandwagon and now thinks they also have to write you poems.

Underneath this, though, it also reveals a deep-seated insecurity Shakespeare has about his position not only in relation to his young lover, but in the society he finds himself operating in as a whole. This is not new:

Sonnet 25

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars,

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most

Sonnet 29

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

Sonnet 37

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth,

So I, made lame by fortune's dearest plight,

all of Sonnet 66, starting with

Tired with all these for restful death I cry

Sonnet 71, ending with

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me, after I am gone.

and then Sonnet 72 doing so with

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

They all attest to the same thing: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am not recognised, not appreciated, not valued by the world at large. What sustains me is you: with your love, with your friendship, perhaps – we don't know – also with your patronage, which may or may not come with direct financial support, it may simply come with the glamour of association. And now, these other poets, who know you nowhere near as well as I do, who have no real, genuinely felt and experienced love for you, who are mere opportunists and who, by the way, therefore not only don't deserve but also do not need your support, because they already are part of the clique of learned, maybe even aristocratic elite, are muscling in on my game.

That there is an existential component to this will become clearer as we go along. this first Rival Poet poem does not yet express either despair or acute fear for his love, that is yet to come, what Sonnet 78 does is note – in notably generalised terms, speaking, as it does in the plurality of 'every alien pen', of 'others' works' and of 'arts' – that there is something going on that encroaches on what Shakespeare feels is his territory.

This, of course, raises two immediately interesting questions: first and most obvious, what happened? What actually is the cause of this response by Shakespeare. That it is a response to something that has happened or, to be more precise, to something that is now going on, is evident in the fact that the poem exists: you do not write a poem to your reader of – as you yourself have just stated in Sonnet 76 and now reiterated in this one – many, many sonnets, that he should value your output more highly than that of others if you are not made aware in some way or other that others are dedicating their writing to your lover too. So is this something Shakespeare just becomes aware of, or is it something the young man has pointed out to Shakespeare? We noted just very recently, in the Halfway Point Summary, that it becomes clear early on that these sonnets do not only not stand in isolation from each other, but they also are not in any way separate from the lives Shakespeare and his lover lead, but that they form part of an ongoing communication both within and outwith these sonnets.

For an answer to this question we have to bide our time a bit, but not for long. Sonnet 83 will directly address it. So leaving this suspended in the room just for the time-being, the second and by some degree more intricate, because both social and psychological question is this: what gives Shakespeare reason, indeed, if he feels so strongly, the right to see himself so threatened? What, if anything makes it reasonable for Shakespeare to consider this his territory, as we called it a moment ago.

Shakespeare himself in Sonnet 82 will speak to this too, when he concedes, "I grant, thou wert not married to my Muse," but as we shall see, he qualifies this statement then in a similar way as he positions himself now. Sonnet 78 unequivocally states – and Sonnet 82 will do so again – I am special. You are special to me because you are 'all my art', which implies not only that I receive all my skill from you, but also that I devote all of my skill to you, and what I write is 'thine and borne of thee'.

This may mean nothing more than that our poet is deluded, of course, It may be the case that Shakespeare finds himself in an entirely one-directional expenditure of emotion and commitment to a young man who did never, who doesn't now, and who is unlikely ever to grant any kind of exclusive attention, affection, favour, or love just to Will. And indeed his behaviour and conduct – throughout the escapades between Sonnets 33 and 42, the unexplained absence alluded to in Sonnets 57 & 58, the other people who are 'all too near' in Sonnet 61, and the reputational damage alluded to in Sonnets 69 & 70 – have suggested quite as much: this young man will not be tied down and he will not be reined in and he will not be told whom to see, what to do, or whose poetry to give his patronage to, for that matter.

So Shakespeare has no leg to stand on? This is hard to imagine. "Those tears are pearl that thy love sheds" – Sonnet 34 – "No more be grieved at that which thou hast done" – Sonnet 35 – "That thou be blamed shall not be thy defect" – Sonnet 70: time and again Shakespeare forgives his young man his transgressions, his fickleness, his deep flaws, and time and again he returns him to, as he tells him in Sonnet 48, "Where thou art not, though I feel thou art: | Within the gentle closure of my breast, | From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part."

And for this to be happening over so many sonnets and therefore over such an extended period – we don't know how long this period is exactly at this point, though we will get a very clear indication of it before this series is through – there has to be a good reason. And of course the only good reason that anyone could find in such a situation to persevere, not to give up on their lover, to not throw in the towel, is that the lover does keep coming back. That he does return your feelings, and shows them, that he does need and want and love you too.

Sonnet 78, signalling as it does a jealousy, also signals that such a jealousy may be justified. To the extent, at least, that jealousy ever can be. And in doing so it offers us one further confirmation that this relationship of which we think and speak, between our poet and his young, petulant lover, is real. That it has a foundation and that it has a substance and that it has an arc. And it is therefore both mildly ironic and also only too natural and human that it also, not least by virtue of the fact that it needs to be written, marks the short beginning of the very long end to this extraordinary relationship...

Sonnet 78 also happens to mark the beginning of the second half of the collection of 154 sonnets originally published in 1609, and thus ushers in a major new phase in the numbered sequence, although whether or not this is deliberate, we cannot tell. What we do know from this sonnet and its companions is that here begins a whole new crisis for William Shakespeare, which will have a profound and lasting effect on him and his relationship with the young man.

At first glance, Sonnet 78, in its tone and its construction, strikes us as nothing so much as peeved. Shakespeare is saying to his young man: I compose all these beautiful, loving sonnets for you, and what happens? Everybody else jumps on the bandwagon and now thinks they also have to write you poems.

Underneath this, though, it also reveals a deep-seated insecurity Shakespeare has about his position not only in relation to his young lover, but in the society he finds himself operating in as a whole. This is not new:

Sonnet 25

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars,

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most

Sonnet 29

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

Sonnet 37

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth,

So I, made lame by fortune's dearest plight,

all of Sonnet 66, starting with

Tired with all these for restful death I cry

Sonnet 71, ending with

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me, after I am gone.

and then Sonnet 72 doing so with

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

They all attest to the same thing: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am not recognised, not appreciated, not valued by the world at large. What sustains me is you: with your love, with your friendship, perhaps – we don't know – also with your patronage, which may or may not come with direct financial support, it may simply come with the glamour of association. And now, these other poets, who know you nowhere near as well as I do, who have no real, genuinely felt and experienced love for you, who are mere opportunists and who, by the way, therefore not only don't deserve but also do not need your support, because they already are part of the clique of learned, maybe even aristocratic elite, are muscling in on my game.

That there is an existential component to this will become clearer as we go along. this first Rival Poet poem does not yet express either despair or acute fear for his love, that is yet to come, what Sonnet 78 does is note – in notably generalised terms, speaking, as it does in the plurality of 'every alien pen', of 'others' works' and of 'arts' – that there is something going on that encroaches on what Shakespeare feels is his territory.

This, of course, raises two immediately interesting questions: first and most obvious, what happened? What actually is the cause of this response by Shakespeare. That it is a response to something that has happened or, to be more precise, to something that is now going on, is evident in the fact that the poem exists: you do not write a poem to your reader of – as you yourself have just stated in Sonnet 76 and now reiterated in this one – many, many sonnets, that he should value your output more highly than that of others if you are not made aware in some way or other that others are dedicating their writing to your lover too. So is this something Shakespeare just becomes aware of, or is it something the young man has pointed out to Shakespeare? We noted just very recently, in the Halfway Point Summary, that it becomes clear early on that these sonnets do not only not stand in isolation from each other, but they also are not in any way separate from the lives Shakespeare and his lover lead, but that they form part of an ongoing communication both within and outwith these sonnets.

For an answer to this question we have to bide our time a bit, but not for long. Sonnet 83 will directly address it. So leaving this suspended in the room just for the time-being, the second and by some degree more intricate, because both social and psychological question is this: what gives Shakespeare reason, indeed, if he feels so strongly, the right to see himself so threatened? What, if anything makes it reasonable for Shakespeare to consider this his territory, as we called it a moment ago.

Shakespeare himself in Sonnet 82 will speak to this too, when he concedes, "I grant, thou wert not married to my Muse," but as we shall see, he qualifies this statement then in a similar way as he positions himself now. Sonnet 78 unequivocally states – and Sonnet 82 will do so again – I am special. You are special to me because you are 'all my art', which implies not only that I receive all my skill from you, but also that I devote all of my skill to you, and what I write is 'thine and borne of thee'.

This may mean nothing more than that our poet is deluded, of course, It may be the case that Shakespeare finds himself in an entirely one-directional expenditure of emotion and commitment to a young man who did never, who doesn't now, and who is unlikely ever to grant any kind of exclusive attention, affection, favour, or love just to Will. And indeed his behaviour and conduct – throughout the escapades between Sonnets 33 and 42, the unexplained absence alluded to in Sonnets 57 & 58, the other people who are 'all too near' in Sonnet 61, and the reputational damage alluded to in Sonnets 69 & 70 – have suggested quite as much: this young man will not be tied down and he will not be reined in and he will not be told whom to see, what to do, or whose poetry to give his patronage to, for that matter.

So Shakespeare has no leg to stand on? This is hard to imagine. "Those tears are pearl that thy love sheds" – Sonnet 34 – "No more be grieved at that which thou hast done" – Sonnet 35 – "That thou be blamed shall not be thy defect" – Sonnet 70: time and again Shakespeare forgives his young man his transgressions, his fickleness, his deep flaws, and time and again he returns him to, as he tells him in Sonnet 48, "Where thou art not, though I feel thou art: | Within the gentle closure of my breast, | From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part."

And for this to be happening over so many sonnets and therefore over such an extended period – we don't know how long this period is exactly at this point, though we will get a very clear indication of it before this series is through – there has to be a good reason. And of course the only good reason that anyone could find in such a situation to persevere, not to give up on their lover, to not throw in the towel, is that the lover does keep coming back. That he does return your feelings, and shows them, that he does need and want and love you too.

Sonnet 78, signalling as it does a jealousy, also signals that such a jealousy may be justified. To the extent, at least, that jealousy ever can be. And in doing so it offers us one further confirmation that this relationship of which we think and speak, between our poet and his young, petulant lover, is real. That it has a foundation and that it has a substance and that it has an arc. And it is therefore both mildly ironic and also only too natural and human that it also, not least by virtue of the fact that it needs to be written, marks the short beginning of the very long end to this extraordinary relationship...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!