Sonnet 29: When in Disgrace With Fortune and Men's Eyes

|

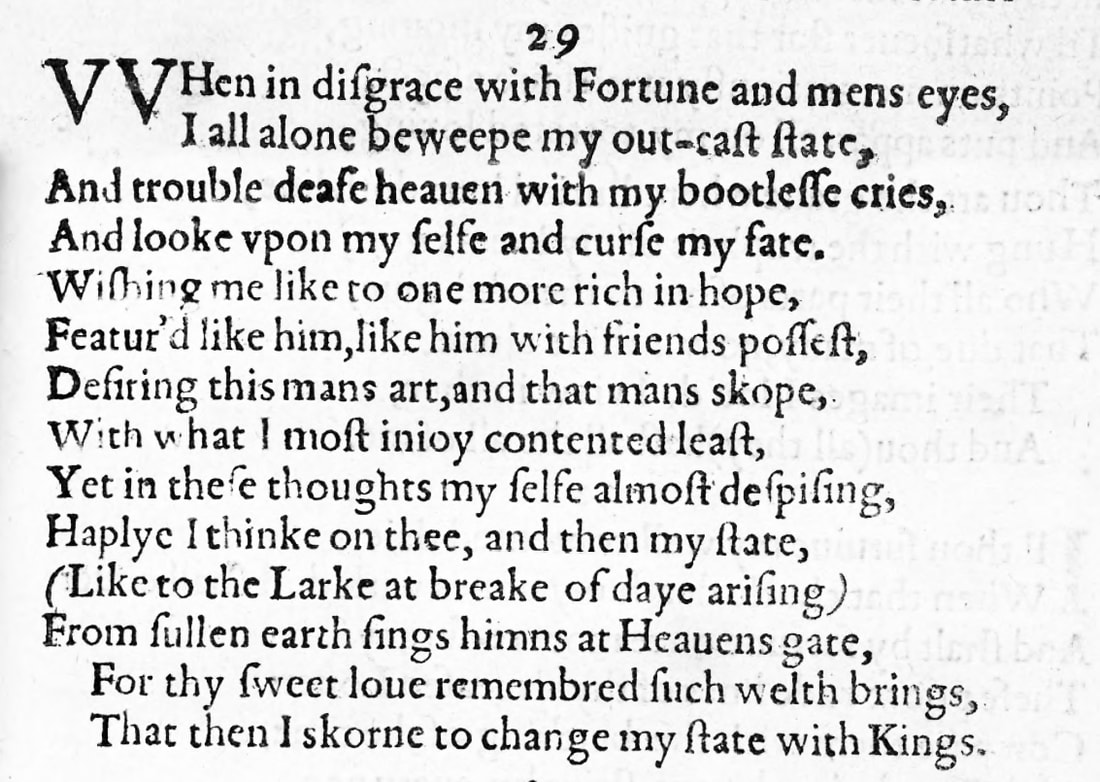

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featured like him, like him with friends possessed, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least, Yet in these thoughts, myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth sings hymns at heaven's gate, For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. |

|

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes

|

When I am out of luck and out of favour with other people...

Being 'in disgrace' with men's eyes suggests that I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am not enjoying the kind of reputation that I crave and, perhaps even stronger, that I am, at the time that I write this, being actively despised by some of my fellow human beings. Whether or not that is the case, we don't know, but we certainly realise in these ten syllables, that William Shakespeare considers himself to be out of grace, and therefore out of favour with both society and with fortune itself, in other words unlucky, unfortunate. |

|

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

|

...I, being all on my own, cry over or bewail my state as an outcast person...

This sense of isolation and loneliness quite possibly stems from being away from home and from the young lover as well, as has been established by the previous two sonnets. |

|

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries

|

...and, with my useless and wholly ineffectual cries or outbursts trouble a heaven that is deaf to my woes and worries, in other words, heaven of course cannot and therefore will not do anything about my dejected state of unhappiness...

'Heaven' here can be pronounced either as one syllable, 'hea'n' or as two syllables. What somewhat favours the former is that it should rhyme with the first line of the poem, which is a perfect iambic pentameter. |

|

And look upon myself and curse my fate,

|

...and I look at myself and I curse my fate...

|

|

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

|

...comparing myself to others and wishing I were more like somebody who has more hope than I do...

|

|

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

|

...and I wish I could look like someone who is good looking, and have a good and powerful circle of friends...

This and the previous line sound like they might be talking about one person who has all these great benefits of life, but the next line suggests that Shakespeare is really drawing up a list of different people who all have something he does not have but wishes he had, so we can also – and probably should – read these as three examples he cites: one who is rich in hope, one who is well-featured, and one who has many friends. |

|

Desiring this man's art and that man's scope,

|

...and I envy yet another man's art, meaning his skill and possibly by extension his success, and some other man's scope, meaning his power, his influence, his overall capability to be the agent of his own volition...

|

|

With what I most enjoy contented least,

|

...so much so that even the things I enjoy most in life satisfy me the least.

William Shakespeare does not tell us what he enjoys most in life, it could be acting, it could be writing, it could be any other activity from which he would normally derive pleasure, but in this instance there really is nothing that hints at any sexual connotation: it seems to be a very straightforward line that can be read entirely at face value. |

|

Yet in these thoughts, myself almost despising,

|

And yet, when I am weighed down by all these thoughts to the point where I almost despise myself...

|

|

Haply I think on thee, and then my state

|

...I happen to think of you, and then my state...

'Haply' often gets mistaken as 'happily', but this is an important distinction to be made: 'haply' means accidentally, by happenstance. Perhaps Shakespeare – who must have been aware of how similar it sounds to 'happily' – uses it here almost as a pun to anticipate the great happiness he is about to describe: |

|

Like to the lark at break of day arising

|

...like a lark that rises up to the sky at the break of day...

|

|

From sullen earth sings hymns at heaven's gate

|

...having taken off from the dark and gloomy earth, now sings hymns at the gate of heaven.

There's an interesting minor convolution here, because the subject of this line is 'my state' which, just like a lark that rises up to the sky, sings hymns, but the line also describes the lark, who himself appears to be, metaphorically, singing hymns 'at heaven's gate', heaven's gate being the entrance to a place of eternal bliss, a Nirvana or Elysium, so to speak. |

|

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings. |

Because just remembering your sweet – for which read wonderful in every way – love brings me such great wealth in terms of happiness and wellbeing that then I would disdainfully refuse to swap places with a king, meaning of course, that then, when I think of you, I feel happier than the wealthiest, most powerful man in the country.

|

One of the most celebrated poems in the canon, Sonnet 29 casts William Shakespeare in a state of deep and lonely unhappiness, from which the memory of his young lover is able to lift him in spectacular fashion. By continuing the theme of weariness and dejection established by the previous two sonnets, it confirms our notion of Shakespeare being on the road, away from the young man, but rather than focusing on a longing desire to be with him, it rejoices in the love experienced before.

Sonnet 29 is, in tone, in content, in emotional range, wholly different from Sonnet 18, and so a comparison is both unnecessary and mostly fruitless, except that they have one thing in common that in both instances may in part account for their great popularity: they are both comparatively easy to understand. But since Sonnet 18 – and from what we have seen and experienced until now, we have no reason not to read them as an actual chronological sequence – the relationship has moved on substantially: when the first 17 sonnets all concerned themselves with the question of the young man's procreation, Sonnet 18 marked the beginning of Shakespeare's direct and undisguised adoration of, and even infatuation with, the young man, and seeing that the connection between the two and therefore the relationship – as far as we can tell – is rooted in poetry, it is not even surprising that Sonnet 18 cements this relationship in the poem itself, claiming, rightly as it turns out, that "So long as men can breathe or eyes can see | So long lives this, and this gives life to thee."

We saw in Sonnets 22 and 25 how, gradually, William Shakespeare gained and expressed the sense that his love for the young man was reciprocated, and how, just before or just after being called away from him he writes to acknowledge their difference in status and therefore indeed state, in Sonnet 26. Both, Sonnets 27 and 28 then left us in no doubt about how much Shakespeare misses the young man, being away from him, and how he is tormented by this absence, and now, with Sonnet 29 an exquisite ray of hope and joy enters into his disposition through remembering his 'sweet love'.

We don't know what brings this on. And nothing in this poem allows us to draw any conclusions. All we know and, more than know sense, incredibly strongly, is that William Shakespeare, from the dejection and tired drudge of his toil and travel is finding inspiration to jubilantly exult in the love he has experienced. Is it possible that their relationship has had the opportunity, before Shakespeare departed to go on his journey, to move onto a closer, more intimate footing? It is possible, but nothing in Sonnets 27 and 28 hints at that. Has the young man written to Shakespeare to reassure him of his love? Maybe. Has he perhaps even communicated some kind of promise for when Shakespeare returns? That too is not without the bounds of possibilities, but we are speculating wildly here if we suggest so.

Going by the words, and by the words only – which is after all the declared approach – what we know is that when Shakespeare finds reason to consider himself dejected, outcast, unfavoured by fortune, the memory alone of the young man raises him up to the point where he would scorn to change his state with kings. Of course, comparing the riches bestowed on you by your love to those of a king is something of a poetic commonplace, but it is perhaps worth reminding ourselves at this point what the world is like that Shakespeare inhabits. The wealth and power of a King or – as it in all conceivable likelihood still is at the time Shakespeare writes this – Queen of England is no longer absolute, but it comes close: lands, titles, honours, livelihoods and lives are in the gift of the monarch and the state of a king is the highest that can be attained. There is nobody more privileged, more exulted, except God. And the birthright of the monarch is, after all, considered divinely ordained. So saying that you would scorn to change your state with kings is rich indeed.

And – whether he does so consciously or no – Shakespeare draws our attention to status and state more than at a cursory glance we may at first be aware: he uses the exact same word 'state' three times. And in each case it holds a meaning of both 'status' – as in my station in life – and 'disposition', as in my state of mind and being. In this sonnet, as in the sonnet that follows, William Shakespeare realises that although he may not have everything that he wants, and although the world is perhaps not fair and his position in life is more lowly than he wished, he has one thing that trumps everything: he has love. It is almost a bit as if Eden Ahbez's Nature Boy had come to visit him from the future and made him realise that "the greatest thing you'll ever learn | is just to love and be loved in return."

And this, then, perhaps, is the principal reason we relate to this sonnet so readily and render it so often: in our gloomiest moments it is hope that sustains us, it is the memory of better days which feeds that hope, and it is love that gives us the power to go on. In Sonnet 29 our poet connects with us and the human condition in this simple but profound way, and Sonnet 30 will weave the same thread further into the fabric of his being. Things are looking up for William Shakespeare and for a short while he has every reason to rejoice. But all too soon there will be dark clouds gathering on the horizon...

Sonnet 29 is, in tone, in content, in emotional range, wholly different from Sonnet 18, and so a comparison is both unnecessary and mostly fruitless, except that they have one thing in common that in both instances may in part account for their great popularity: they are both comparatively easy to understand. But since Sonnet 18 – and from what we have seen and experienced until now, we have no reason not to read them as an actual chronological sequence – the relationship has moved on substantially: when the first 17 sonnets all concerned themselves with the question of the young man's procreation, Sonnet 18 marked the beginning of Shakespeare's direct and undisguised adoration of, and even infatuation with, the young man, and seeing that the connection between the two and therefore the relationship – as far as we can tell – is rooted in poetry, it is not even surprising that Sonnet 18 cements this relationship in the poem itself, claiming, rightly as it turns out, that "So long as men can breathe or eyes can see | So long lives this, and this gives life to thee."

We saw in Sonnets 22 and 25 how, gradually, William Shakespeare gained and expressed the sense that his love for the young man was reciprocated, and how, just before or just after being called away from him he writes to acknowledge their difference in status and therefore indeed state, in Sonnet 26. Both, Sonnets 27 and 28 then left us in no doubt about how much Shakespeare misses the young man, being away from him, and how he is tormented by this absence, and now, with Sonnet 29 an exquisite ray of hope and joy enters into his disposition through remembering his 'sweet love'.

We don't know what brings this on. And nothing in this poem allows us to draw any conclusions. All we know and, more than know sense, incredibly strongly, is that William Shakespeare, from the dejection and tired drudge of his toil and travel is finding inspiration to jubilantly exult in the love he has experienced. Is it possible that their relationship has had the opportunity, before Shakespeare departed to go on his journey, to move onto a closer, more intimate footing? It is possible, but nothing in Sonnets 27 and 28 hints at that. Has the young man written to Shakespeare to reassure him of his love? Maybe. Has he perhaps even communicated some kind of promise for when Shakespeare returns? That too is not without the bounds of possibilities, but we are speculating wildly here if we suggest so.

Going by the words, and by the words only – which is after all the declared approach – what we know is that when Shakespeare finds reason to consider himself dejected, outcast, unfavoured by fortune, the memory alone of the young man raises him up to the point where he would scorn to change his state with kings. Of course, comparing the riches bestowed on you by your love to those of a king is something of a poetic commonplace, but it is perhaps worth reminding ourselves at this point what the world is like that Shakespeare inhabits. The wealth and power of a King or – as it in all conceivable likelihood still is at the time Shakespeare writes this – Queen of England is no longer absolute, but it comes close: lands, titles, honours, livelihoods and lives are in the gift of the monarch and the state of a king is the highest that can be attained. There is nobody more privileged, more exulted, except God. And the birthright of the monarch is, after all, considered divinely ordained. So saying that you would scorn to change your state with kings is rich indeed.

And – whether he does so consciously or no – Shakespeare draws our attention to status and state more than at a cursory glance we may at first be aware: he uses the exact same word 'state' three times. And in each case it holds a meaning of both 'status' – as in my station in life – and 'disposition', as in my state of mind and being. In this sonnet, as in the sonnet that follows, William Shakespeare realises that although he may not have everything that he wants, and although the world is perhaps not fair and his position in life is more lowly than he wished, he has one thing that trumps everything: he has love. It is almost a bit as if Eden Ahbez's Nature Boy had come to visit him from the future and made him realise that "the greatest thing you'll ever learn | is just to love and be loved in return."

And this, then, perhaps, is the principal reason we relate to this sonnet so readily and render it so often: in our gloomiest moments it is hope that sustains us, it is the memory of better days which feeds that hope, and it is love that gives us the power to go on. In Sonnet 29 our poet connects with us and the human condition in this simple but profound way, and Sonnet 30 will weave the same thread further into the fabric of his being. Things are looking up for William Shakespeare and for a short while he has every reason to rejoice. But all too soon there will be dark clouds gathering on the horizon...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!