Sonnet 49: Against That Time, if Ever That Time Come

|

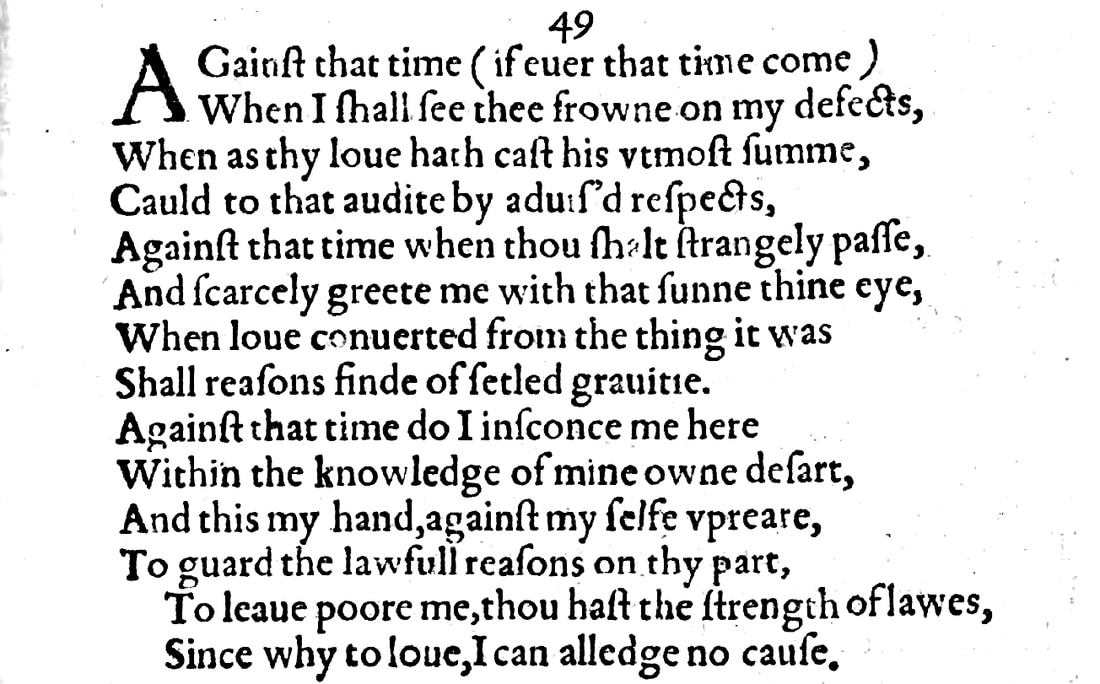

Against that time, if ever that time come,

When I shall see thee frown on my defects, Whenas thy love hath cast his utmost sum, Called to that audit by advised respects; Against that time when thou shalt strangely pass And scarcely greet me with that sun, thine eye, When love, converted from the thing it was, Shall reasons find of settled gravity; Against that time do I ensconce me here, Within the knowledge of mine own desert, And this, my hand, against myself uprear To guard the lawful reasons on thy part: To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws, Since why to love, I can allege no cause. |

|

Against that time, if ever that time come,

When I shall see thee frown on my defects, |

Against that time – if ever such a time were to come – when I see you frown at my faults, when you effectively criticise me, be it in words or just with an expresson of disdain on your face, when you take umbrage at my weaknesses and failings...

The premise is, of course, that one's lover would gladly overlook and tolerate one's flaws and forgive one's mistakes, and such a time would therefore signal the end of love, as is now further expounded: |

|

Whenas thy love hath cast his utmost sum,

Called to that audit by advised respects; |

...when your love has been counted up and considered to be as much as you can spend on me, as advised by some respectable authority, in the way an accountant might advise someone not to spend any more money now, because they are in danger of overreaching themselves.

While to us this may sound like a strange notion, for a young nobleman of – as we believe we may assume – extremely high status this, especially at the time, would not be at all unlikely: his personal advisers or people around him of similar status and high authority might very well counsel him against continuing a relationship such as this; although the line can also be read simply as referring to the young man's own careful considerations, which would make these his own 'advised respects'. |

|

Against that time when thou shalt strangely pass

And scarcely greet me with that sun, thine eye, |

Against such a time when you may pass me in the street like a stranger and scarcely even look at me and greet me with your eye, which is like a sun to me...

This too is not as unheard of as it may seem. London at the time is a walled city of about 150,000 inhabitants: comparable to a small to midsize European city today, like Basel or Bern, for example. Meeting someone you know in the town centre happens regularly and almost by default, and someone who is in the public eye but who has found they can no longer be associated with you would quite possibly simply not stop but 'walk on by', as Hal David has Dionne Warwick put it in Burt Bacharach's soulful tune almost exactly four hundred years later. |

|

When love, converted from the thing it was,

Shall reasons find of settled gravity; |

...when your love will have changed from what it was into something else – maybe indifference, maybe mere absence of love – and will find reasons for you to behave in a formal, serious, even grave way towards me.

|

|

Against that time do I ensconce me here,

Within the knowledge of mine own desert, |

...against such a time do I here now fortify myself, within the full knowledge of my own worth and place in the world.

'Ensconce' today means "to establish or settle (someone) in a comfortable, safe place," but the earlier meaning that applies here is "to shelter within or behind a walled fortification," (Oxford Dictionaries), and so I am effectively shoring myself up within my own understanding of myself, but this understanding and sense of self-worth is ambiguous: it suggests, on the one hand, that I know my limitations, but also that I am aware of what worth I have. The way the sonnet continues though leaves doubt as to Shakespeare's sense of self-confidence: |

|

And this, my hand, against myself uprear

To guard the lawful reasons on thy part: |

And I raise this, my own hand, against myself, as a person might do who raises their hand in court to swear an oath as a witness, or indeed as someone might raise their hand at a wedding ceremony if they knew of any lawful reason why someone shouldn't wed. And I do so not to defend myself, but to protect your rights:

|

|

To leave poor me, thou hast the strength of laws

Since why to love, I can allege no cause. |

You are fully within your rights to leave me, because I can allege no reason why you should love me.

|

The soberly solemn Sonnet 49 opens an unnervingly real register that does away with hyperbolic praise, clever contrivance, or poetic acrobatics, and instead drives through a short structured sequence of dreaded but perfectly plausible scenarios towards a devastating denouement. Seldom until now and rarely hereafter do we hear Shakespeare quite so roundly, so comprehensively, and above all so authentically self-aware and self-effacing.

The positioning of the poem is worth paying brief attention to, as it appears to be part of this extended period of absence of which we have spoken several times now and which clearly has established itself since Sonnet 42. Whether chronologically it belongs here we can't, as with the vast majority of these sonnets, be certain of, but it makes sense. If so, Shakespeare appears to effectively forestall any disappointment on his return. This too would align believably with Sonnet 48 which precedes it but with which it does not form a pair, as the previous two couples of sonnets have done with each other respectively.

In Sonnet 48, Shakespeare worries that before going away he was unable to lock up his most precious treasure, the young man, other than in his heart, where, however, he is not tied down but free to come and go as he pleases. This freedom did not sound like one that Shakespeare is overly happy with, but a fact of life he has is learning to live with.

As a direct sequential successor to Sonnet 48, Sonnet 49 increases the anxiety and raises the discomfiture to the level where William Shakespeare is effectively saying to the young man: I understand if you can't or don't love me the way I love you, because I see no reason why you should. This from a man with such a gift for language and such an ability to express his own affection, admiration, longing, and, indeed, desire, is nothing short of heartbreaking. Which in a somewhat cynically minded person might prompt – and not unreasonably – the question: but is it true? Is Shakespeare here really being authentic, as just a moment I purported he is, or is he being a drama queen. There is that possibility: the poem is saying in those actual words: "poor me." And so no, we can't rule it out. Far from authentic, genuine, heartfelt, it is conceivable that Shakespeare is sending a note to his lover saying: affirm me. Validate me. Make me feel better about myself, write to me!

Which it is, we cannot tell with certainty. And in this particular case I am even minded to deploy my default position cautiously, which is to say that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend, because we simply don't know enough about Shakespeare and his young man to declare in this instance what is likely and what isn't. Whence then this bold assertion above that this sonnet is 'real' and 'authentically self-aware'?

The words. We only have the words, but they are telling. They are factual. Measured. They allow for doubt – "if ever that time come" – they describe, as we saw when looking at their meaning, a time that may all too easily come about. If you are in love with someone and you are away from them and you haven't heard from them in weeks, and their position in life and society is such that they are essentially out of your league in every imaginable way possible, as we have fairly firm grounds to believe the young man is in relation to Shakespeare, then the dread end of this relationship in just the terms invoked is all too real.

The one note that is struck in this sonnet that to our ears sounds potentially off is exactly the one already mentioned, "poor me." To our ears that's at the very least a bit uncool. And here we may perhaps do well to show some leniency to Will, because at the time he writes this he very possibly has good reason to think of himself as 'poor', in more ways than one. Never even mind the state of the relationship and the upheaval that his young lover's infidelity has caused, and quite apart from the fact that he is away from home with no real idea of what is going on in his life, if the timing of the sonnet lies even approximately where we may suppose it does and if it sits even roughly in the right place in the sequence, then Shakespeare is going through a rough patch in his writing career, with the fact alone that he is away from London suggesting that he is having to resort to touring or teaching to make ends meet financially, with ups and downs in his relationship of which the ups are ecstatic and the downs are profound.

This would seem to be one of the lows and because the poem is so devoid of verbosity in either direction – there have been sonnets before and there are sonnets to follow which express both peaks and troths with much more forceful vocabulary – I am deeply inclined to give this sonnet its due and suggest that it speaks directly, appallingly, from the heart.

What the sonnet also does – and this almost pales into insignificance by comparison, but not quite – is further add to the profile we are assembling of our young man. We haven't expended all that much thought on him and his person for a little while recently, certainly not since the 'incident' with Shakespeare's mistress around Sonnets 33 to 35 and 40 to 41, but when we think of the kind of young English nobleman we have so far fairly consistently been getting the impression we are dealing with, then everything this sonnet says fits. Therein lies – quite apart from its extraordinary impact – among others its great value as a piece of 'evidence'.

Every so often you hear people question this profile of a young English nobleman and posit that Shakespeare would not dare to say some to the things he says to, say, a Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, or to a William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke, for that matter. And yet, that is exactly the kind of person to whom the kind of things this sonnet – along with many, many others – expresses would apply.

If the young man, with whom Shakespeare finds himself in this extraordinarily complex and layered relationship, were another poet of his own standing, an actor in his company, the son of a landlady, then this sonnet – along with many, many others – simply wouldn't make sense. But the kind of person who would be entirely within their rights to say to William Shakespeare at some point, I am so sorry, but my life does call me into a different direction now, and no reasonable person, no matter how smitten, could argue otherwise at that time, is exactly as we have been forming the impression: a young, exceptionally well-connected, powerful, and highly visible member of the aristocracy.

The overriding sensation imparted by Sonnet 49 though is sadness. Because whether William Shakespeare – greatest poet in the English language ever to have lived as far as we know – has genuine reason to feel so dejected, or whether he is warding off against feeling so dejected because he fears that he may soon do so; whether he most deep down in his heart thinks of himself at this moment as 'poor me', or whether this is a cry for attention, or quite possibly something of a mixture of both; whether the young man he is in love with has given him reason for this self-doubt, or simply been incommunicado, or just hasn't realised how his poet friend is suffering; whether William Shakespeare ever wanted him, us, or anyone else to ever read these lines and discuss them in great detail or not; whether or not the poem is actually even addressed to the same young man as the others or to someone else or to a fantasy or to an imaginary lover or to an entity we haven't yet thought of: hearing a man with a soul that runs deep and heart that is so worn on the sleeve of his pages say "since why to love I can allege no cause" is simply abysmally sad. Everyone, surely, has something about themselves of which they know it is lovable. I daresay William Shakespeare knows of things that make him lovable, which on a better day he can and does think of and write about, not least when he tells us and his young lover that his lines will live forever and in doing so keep the young man alive as long.

But today, with Sonnet 49, our Will is low and not afraid to say so. This too shall pass though. Things will look up – in every way imaginable – soon, and till they do, two sonnets follow next that give us a yet stronger and more vivid sense of what being on the road and away from his young lover is like for William Shakespeare.

The positioning of the poem is worth paying brief attention to, as it appears to be part of this extended period of absence of which we have spoken several times now and which clearly has established itself since Sonnet 42. Whether chronologically it belongs here we can't, as with the vast majority of these sonnets, be certain of, but it makes sense. If so, Shakespeare appears to effectively forestall any disappointment on his return. This too would align believably with Sonnet 48 which precedes it but with which it does not form a pair, as the previous two couples of sonnets have done with each other respectively.

In Sonnet 48, Shakespeare worries that before going away he was unable to lock up his most precious treasure, the young man, other than in his heart, where, however, he is not tied down but free to come and go as he pleases. This freedom did not sound like one that Shakespeare is overly happy with, but a fact of life he has is learning to live with.

As a direct sequential successor to Sonnet 48, Sonnet 49 increases the anxiety and raises the discomfiture to the level where William Shakespeare is effectively saying to the young man: I understand if you can't or don't love me the way I love you, because I see no reason why you should. This from a man with such a gift for language and such an ability to express his own affection, admiration, longing, and, indeed, desire, is nothing short of heartbreaking. Which in a somewhat cynically minded person might prompt – and not unreasonably – the question: but is it true? Is Shakespeare here really being authentic, as just a moment I purported he is, or is he being a drama queen. There is that possibility: the poem is saying in those actual words: "poor me." And so no, we can't rule it out. Far from authentic, genuine, heartfelt, it is conceivable that Shakespeare is sending a note to his lover saying: affirm me. Validate me. Make me feel better about myself, write to me!

Which it is, we cannot tell with certainty. And in this particular case I am even minded to deploy my default position cautiously, which is to say that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend, because we simply don't know enough about Shakespeare and his young man to declare in this instance what is likely and what isn't. Whence then this bold assertion above that this sonnet is 'real' and 'authentically self-aware'?

The words. We only have the words, but they are telling. They are factual. Measured. They allow for doubt – "if ever that time come" – they describe, as we saw when looking at their meaning, a time that may all too easily come about. If you are in love with someone and you are away from them and you haven't heard from them in weeks, and their position in life and society is such that they are essentially out of your league in every imaginable way possible, as we have fairly firm grounds to believe the young man is in relation to Shakespeare, then the dread end of this relationship in just the terms invoked is all too real.

The one note that is struck in this sonnet that to our ears sounds potentially off is exactly the one already mentioned, "poor me." To our ears that's at the very least a bit uncool. And here we may perhaps do well to show some leniency to Will, because at the time he writes this he very possibly has good reason to think of himself as 'poor', in more ways than one. Never even mind the state of the relationship and the upheaval that his young lover's infidelity has caused, and quite apart from the fact that he is away from home with no real idea of what is going on in his life, if the timing of the sonnet lies even approximately where we may suppose it does and if it sits even roughly in the right place in the sequence, then Shakespeare is going through a rough patch in his writing career, with the fact alone that he is away from London suggesting that he is having to resort to touring or teaching to make ends meet financially, with ups and downs in his relationship of which the ups are ecstatic and the downs are profound.

This would seem to be one of the lows and because the poem is so devoid of verbosity in either direction – there have been sonnets before and there are sonnets to follow which express both peaks and troths with much more forceful vocabulary – I am deeply inclined to give this sonnet its due and suggest that it speaks directly, appallingly, from the heart.

What the sonnet also does – and this almost pales into insignificance by comparison, but not quite – is further add to the profile we are assembling of our young man. We haven't expended all that much thought on him and his person for a little while recently, certainly not since the 'incident' with Shakespeare's mistress around Sonnets 33 to 35 and 40 to 41, but when we think of the kind of young English nobleman we have so far fairly consistently been getting the impression we are dealing with, then everything this sonnet says fits. Therein lies – quite apart from its extraordinary impact – among others its great value as a piece of 'evidence'.

Every so often you hear people question this profile of a young English nobleman and posit that Shakespeare would not dare to say some to the things he says to, say, a Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, or to a William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke, for that matter. And yet, that is exactly the kind of person to whom the kind of things this sonnet – along with many, many others – expresses would apply.

If the young man, with whom Shakespeare finds himself in this extraordinarily complex and layered relationship, were another poet of his own standing, an actor in his company, the son of a landlady, then this sonnet – along with many, many others – simply wouldn't make sense. But the kind of person who would be entirely within their rights to say to William Shakespeare at some point, I am so sorry, but my life does call me into a different direction now, and no reasonable person, no matter how smitten, could argue otherwise at that time, is exactly as we have been forming the impression: a young, exceptionally well-connected, powerful, and highly visible member of the aristocracy.

The overriding sensation imparted by Sonnet 49 though is sadness. Because whether William Shakespeare – greatest poet in the English language ever to have lived as far as we know – has genuine reason to feel so dejected, or whether he is warding off against feeling so dejected because he fears that he may soon do so; whether he most deep down in his heart thinks of himself at this moment as 'poor me', or whether this is a cry for attention, or quite possibly something of a mixture of both; whether the young man he is in love with has given him reason for this self-doubt, or simply been incommunicado, or just hasn't realised how his poet friend is suffering; whether William Shakespeare ever wanted him, us, or anyone else to ever read these lines and discuss them in great detail or not; whether or not the poem is actually even addressed to the same young man as the others or to someone else or to a fantasy or to an imaginary lover or to an entity we haven't yet thought of: hearing a man with a soul that runs deep and heart that is so worn on the sleeve of his pages say "since why to love I can allege no cause" is simply abysmally sad. Everyone, surely, has something about themselves of which they know it is lovable. I daresay William Shakespeare knows of things that make him lovable, which on a better day he can and does think of and write about, not least when he tells us and his young lover that his lines will live forever and in doing so keep the young man alive as long.

But today, with Sonnet 49, our Will is low and not afraid to say so. This too shall pass though. Things will look up – in every way imaginable – soon, and till they do, two sonnets follow next that give us a yet stronger and more vivid sense of what being on the road and away from his young lover is like for William Shakespeare.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!