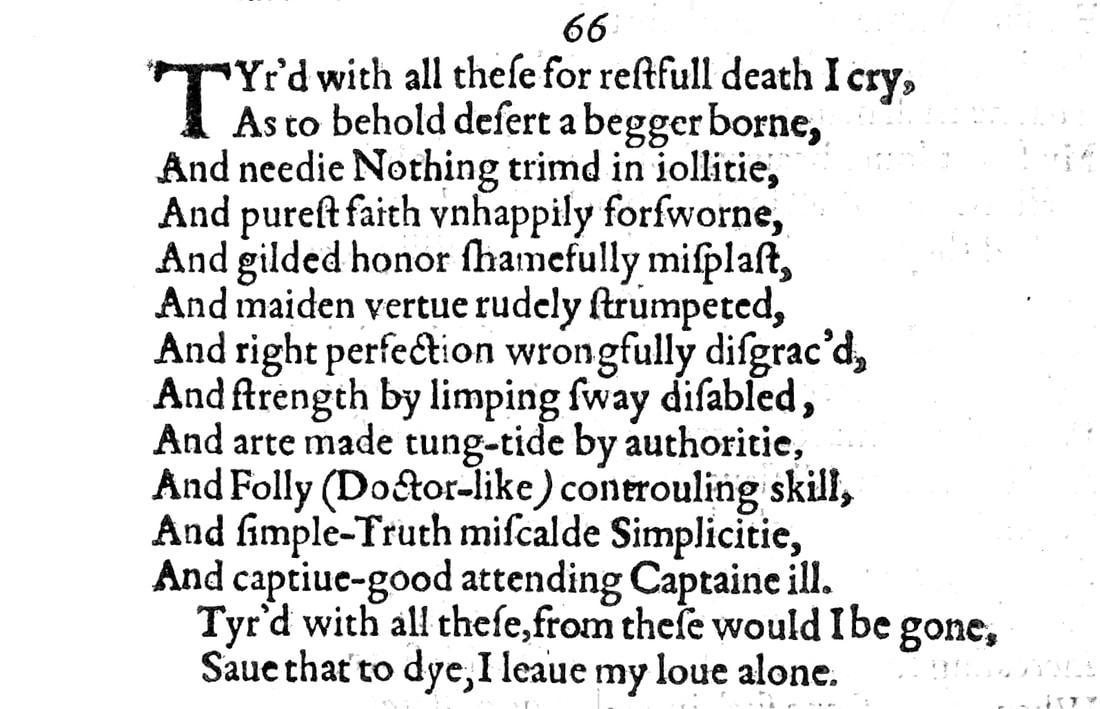

Sonnet 66: Tired With All These, for Restful Death I Cry

|

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry:

As, to behold desert a beggar born, And needy nothing trimmed in jollity, And purest faith unhappily forsworn, And gilded honour shamefully misplaced, And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted, And right perfection wrongfully disgraced, And strength by limping sway disabled, And art made tongue-tied by authority, And folly, doctor-like, controlling skill, And simple truth miscalled simplicity, And captive good attending Captain Ill - Tired with all these, from these would I be gone, Save that to die, I leave my love alone. |

|

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry:

|

Tired with all these things that I am about to list, I cry for restful death:

|

|

As, to behold desert a beggar born,

|

Such as: having to watch how desert – for which read those who are and that which is of merit and therefore deserving of recognition and approval – is born a beggar, meaning that it goes unacknowledged and unrewarded.

|

|

And needy nothing trimmed in jollity,

|

And things or people that are effectively worthless and/or capable of nothing and therefore needy, because they have no merit or quality of their own, are decorated in or rewarded with jollity, for which here read either 'revelry', meaning carefree or possibly also mindless enjoyment, or frivolity, meaning expensive attire and jewellery which clearly, unlike those of desert in the previous line, they do not deserve.

|

|

And purest faith unhappily forsworn,

|

Purest faith, meaning the most truthful, honest, trustworthy people and their genuine actions are betrayed, promises towards them are broken, they are stabbed in the back, for which reason they are unfortunate: this is an unhappy circumstance.

|

|

And gilded honour shamefully misplaced,

|

Honours, which are gilded in the sense that they often come with financial or material rewards, with grand attire, with chains or medals made of gold or other precious metals, are shamefully misplaced, meaning not only are they given to the wrong people, but this is done wittingly, and therefore, since it is intentional, in a manner that is fundamentally corrupt.

For a contemporary example of precisely such a bestowment of wholly unwarranted, unjustifiable, and therefore patently corrupt awarding honours for achievements of which nobody knows what they are meant to be, you need look no further than the elevation of Charlotte Owen to the House of Lords at the age of 30, by the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson who certainly could though he may or may not be her father. |

|

And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted,

|

Maiden virtue, meaning the virtue of purity, of an untarnished reputation, most literally of a virgin woman, but more generally and metaphorically of anyone of whom one could say that they are pure in their intentions and virtuous in their endeavours and behaviour, are rudely 'strumpeted', meaning prostituted, or possibly, by extension, having their good name dragged through the mud or tarnished like that of a prostitute.

Oxford Languages defines 'strumpet' as "dated, humorous: a woman who has many casual sexual encounters or relationships," or as "archaic: a female prostitute." Being 'strumpeted' in Shakespeare's day though is far from humorous or light hearted: if society considered you to be a 'loose' or sexually available woman, this could entirely destroy your position in life, and this level of reputational damage is here being evoked. |

|

And right perfection wrongfully disgraced,

|

Which is more or less what this also alludes to: that someone or something that is genuinely perfect and unblemished is being wrongfully disgraced by slander and lies, whereby this may here be seen as happening in any context, not just in relation to sexual conduct.

|

|

And strength by limping sway disabled,

|

Strength, for which read actual ability, prowess, and potential, is being disabled – held back, limited, curtailed – by a limping sway, meaning an old, decrepit, spent force that receives its authority simply from being in place already, by dint of possessing the right connections or having been born into the right circumstances, into privilege.

|

|

And art made tongue-tied by authority,

|

Art, for which here read skill as well as knowledge and insight is being silenced by authority. This – as indeed all the other instances mentioned – was unquestionably the case in Elizabethan England which operated a ruthlessly authoritarian political regime in which censorship and state interference in the work of writers and artists was par for the course.

|

|

And folly, doctor-like, controlling skill,

|

Folly – meaning ignorance – assumes the air or mantle of a doctor – meaning a learned person – and in this unwarranted, unearnt, and therefore unjustified haughtiness controls actual skill. In other words, the idiots of this world have the upper hand over the real experts, much as you find played out on social media today.

|

|

And simple truth miscalled simplicity,

|

Simple – unvarnished, unadulterated – truth, when expressed in simple, plain terms, is labelled 'simplicity' for which here read simpleness of mind or stupidity in turn.

This line highlights the other end of the spectrum to the previous one: here now it is the simple facts that are being undermined by complicated, convoluted sophistry. |

|

And captive good attending Captain Ill -

|

Good in general – everything that is good, thoughts, deeds, people that are inherently capable of aiding the betterment of society – is held captive by and made to attend or serve 'Captain Ill', meaning everything and everyone that is bad, self-serving, and therefore inherently abusive in this world, but that has been given or assumed the role of 'captain', meaning the person who steers the metaphorical ship of the world.

|

|

Tired with all these, from these would I be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone. |

And here the reiteration of the opening line: tired with all these things, from these would I be gone, by giving up my life, except that to do so would mean leaving my love behind alone.

|

Sonnet 66 to all intents and purposes is a rant. In it, William Shakespeare uses his opening line to tell us that he is about to name just some of the things that make him want to throw in the towel and die. He then lists eleven of these ills in the world and reserves the closing couplet to reiterate that he's really over it and would gladly turn his back on it all, except that to do so would mean leaving his love behind, thus turning his love, for which of course read his lover, into the sole redeeming feature of an existence that has altogether too many things wrong with it.

Sonnet 66 is unique in the canon for several reasons. First and most immediately noticeable, its sheer power of expression. Shakespeare really is not holding back. Instead, he lets rip and in doing so lends his sonnet the second most striking aspect: its structure. This is unlike any of the other 153 sonnets in the standard collection, or any other we know of Shakespeare's for that matter. Editors point to Hamlet's To Be or Not to Be soliloquy which enumerates

"...the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of disprized love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes"

but this carries none of the unrelenting drive of Sonnet 66, whose sole poetic device, apart from the iambic pentameter and a familiar rhyming pattern, is enumeration. There is no breaking this down into an octave and a sestet or even into three internally distinguishable quatrains and a closing couplet. The whole thing is one big outburst with a deep breath at the end for a soothing gesture of affection. And it is a gesture that counts: telling someone – in this case indirectly, since the poem is not addressed to the lover himself but talks about him briefly at the end – that they make even a difficult life worth living is hardly trivial. It could be argued to be the greatest compliment you can make, or certainly one of the greatest.

In this latter observation though – that life for William Shakespeare appears to be barely worth living at the time when he writes this – lies perhaps the sonnet's most important value as a piece of information. Of course, the sonnet on its own and of itself is immensely enjoyable to read and – as we somewhat aim for here with this podcast – to relive, but beyond that it tells us something genuinely significant about where Shakespeare is at. It therefore serves as a useful and fairly dependable guide towards an approximate timing of its composition.

For a poet to be this unhappy, this frustrated, this angry at how things stand in his world, he must find himself undervalued, unrated, unrecognised. The deserving are born beggars and have to go around asking for alms and handouts, rather than being properly recompensed and given the acclaim they deserve. Meanwhile, needy nothing is decorated with what we today would have to call 'celebrity'; faith and trust are rewarded with betrayal, and honours go to entirely the wrong people. The list goes on. Art is made tongue-tied by authority, and folly has an iron grip on genuine skill and actual accomplishment. And most telling of all: simple truth is wilfully misrepresented as 'simplicity'. The poem could have been written this morning, and virtually everything Shakespeare says in it would still be true. And therein lies another great revelation, or perhaps confirmation, of something we can know for practically certain: there is no such thing as 'the good old days'. Things four hundred years ago were exactly as bad as they are now, and in many respects they were a whole lot worse.

Nobody who is in a generally fairly gruntled place needs to let off steam like this. If we continue to assume, as we have been doing from the word go and for very good reasons which we stated early on in the Introduction – and as we have since had affirmed and indeed confirmed by the scholars we have spoken to, even those who take a sceptical view of reading the sonnets 'biographically' – that these sonnets are rooted in lived experience, that they are not mere theoretical writing exercises, but borne out of William Shakespeare's own life situations, then we must conclude from this sonnet that he is going through a rough patch.

This hardly comes as any great surprise: we have been getting the impression for a while now that our poet is deeply preoccupied with his own age, with the age difference between him and his lover, and with mortality and the passing of time generally, and now he presents us with as comprehensive – though hardly exhaustive – a list of items that drive him to distraction and despair as he can fit into fourteen lines.

This is not the poetry of a man who is being celebrated, who is seeing his work read and performed and sold and handsomely paid for, who is making a success of and name for himself in the world. This is the poetry of a man who would dearly wish all of these to be the case and yet finds himself disparaged by his peers while advancing in years, and still unable to get a foothold in his career.

And this means that in all but certainty Sonnet 66 has to have been composed before the end of 1594. Because from the end of 1594 onwards, things start to look up for Shakespeare. The theatres reopen after repeated closures because of the plague, and his troupe of actors becomes the Lord Chamberlain's Men. The Lord Chamberlain holds one of the highest offices at court, closest to the monarch, and so his patronage by definition means that as an actor and playwright you are doing well.

From late 1594, early 1595 onwards, Shakespeare's plays are regularly performed both at the theatre and at court, and with perhaps his principal direct competition, Christopher Marlowe, having been murdered on 30 May 1593, Shakespeare is now becoming the most performed playwright on the English stage. Not only that. Also in 1593, William Shakespeare's long narrative poem, Venus and Adonis, is published, followed in 1594 by The Rape of Lucrece, both of which he has dedicated to the young and exceptionally beautiful and unfathomably rich Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. They both become hits with readers and sell copies in their thousands, and so from late 1594 onwards, William Shakespeare really has no reason to rant. For several years thereafter he is doing wonderfully well, certainly economically and in terms of his status as a writer.

It won't be all plain sailing from thereon in: tragedy is about to strike with a profound impact on him when his eleven-year-old son Hamnet dies in August 1596, but that does not usually prompt a man to rant. It may make a man go into himself and find new depths to his understanding of human life and such meaning as it may have, but even then, the financial rewards and public recognition for his work keep pouring in, and so Sonnet 66 simply does not make sense post-1594. Ever really. Because no matter how difficult the relationship with his young lover becomes, no matter how much he will soon feel put upon by someone encroaching on his territory emotionally and also to some extent professionally, no matter how deeply the loss of his son and therefore heir and bearer of his name gets to him, the bulk of Sonnet 66 only shoulders the weight it does until mid to late 1594, which is, as it happens, soon after Shakespeare has turned thirty.

The sonnet could have been written, in theory, more or less any time before then, but again, we have to ask ourselves: would a young man, newly arrived in town, with everything to play for complain like that? It is really unlikely. I speak from some experience: I arrived in London as a 21-year old, exactly 400 years after Shakespeare left his native Stratford, and for the first few years you are far more likely to be wide-eyed and bushy-tailed than frustrated: you look for opportunities, you find them, you try to make something of them. You meet and associate with new people, you wonder at the multitudes, the cultures, the life. None of this would have been fundamentally different in Shakespeare's day.

Granted, he 'disappears' for seven years before he is mentioned in London. But in order for Robert Greene to take note of him, as he does, in 1592 as an 'upstart crow', Shakespeare has to have had some chance to draw attention to himself. And even if we allow – as we must – for fast-paced living in Elizabethan England, we can still relatively safely assume that Shakespeare arrives in London most likely no later than about 1590/91, aged around 24, 25.

If you have been listening to this podcast, you may remember that Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells in their edition of The Sonnets, which attempts to arrange them in what they themselves call a putative chronological order, following the dating method by Professor Macdonald P Jackson, place the group containing Sonnets 60-77 at just around that time: 1592-96. This on its own would tally with our understanding of the sonnets so far. Where their timing diverges is by putting this entire group before Sonnets 1-59, which for our and most people's understanding of the sonnets creates a massive problem, and we will examine this further when we get to the end of this group with Sonnet 77, which also, as it happens, marks the halfway point in the collection.

For the time-being, what we can say about Sonnet 66 – apart from the fact that it is clearly a singular piece of sonneteering that has virtually no equal in all of Shakespeare's output of the form – is that it gives us a great and unspun insight into William Shakespeare's whole state of being: not just his state of mind, but with a great deal of probability also his standing in the world and his perception of himself as a working writer. And this state of being is, once more, entirely congruent with the other sonnets that we find in its vicinity: the concern with age, the awareness of the passing of time, the wish and need to somehow immortalise his lover. All of this fits and makes sense.

As do the sonnets which are about to follow. Because what comes next is really quite the most extraordinary post-rant whinge at the ways of the world in terms of fashion and people's conduct, stretching over two poems, Sonnets 67 & 68, before, only for the second time in the series so far, William Shakespeare effectively admonishes his young lover, in Sonnet 69. He back-pedals fairly furiously in its companion piece, Sonnet 70, but all of these next ensuing sonnets are well within the tone and atmosphere and comparative mind-muddle that appertain to a man who is not, here and now, standing on what he once, in Sonnet 16 and in relation to his young lover, called "the top of happy hours," but of a man who is feeling put upon, who is sensing his days slip away, who worries about his love too being all to temporary, who realises that he maybe is expected but doesn't know how to nor want to keep up with the fast-changing times, and who has simply had enough of it all.

Sonnet 66 is unique in the canon for several reasons. First and most immediately noticeable, its sheer power of expression. Shakespeare really is not holding back. Instead, he lets rip and in doing so lends his sonnet the second most striking aspect: its structure. This is unlike any of the other 153 sonnets in the standard collection, or any other we know of Shakespeare's for that matter. Editors point to Hamlet's To Be or Not to Be soliloquy which enumerates

"...the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of disprized love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes"

but this carries none of the unrelenting drive of Sonnet 66, whose sole poetic device, apart from the iambic pentameter and a familiar rhyming pattern, is enumeration. There is no breaking this down into an octave and a sestet or even into three internally distinguishable quatrains and a closing couplet. The whole thing is one big outburst with a deep breath at the end for a soothing gesture of affection. And it is a gesture that counts: telling someone – in this case indirectly, since the poem is not addressed to the lover himself but talks about him briefly at the end – that they make even a difficult life worth living is hardly trivial. It could be argued to be the greatest compliment you can make, or certainly one of the greatest.

In this latter observation though – that life for William Shakespeare appears to be barely worth living at the time when he writes this – lies perhaps the sonnet's most important value as a piece of information. Of course, the sonnet on its own and of itself is immensely enjoyable to read and – as we somewhat aim for here with this podcast – to relive, but beyond that it tells us something genuinely significant about where Shakespeare is at. It therefore serves as a useful and fairly dependable guide towards an approximate timing of its composition.

For a poet to be this unhappy, this frustrated, this angry at how things stand in his world, he must find himself undervalued, unrated, unrecognised. The deserving are born beggars and have to go around asking for alms and handouts, rather than being properly recompensed and given the acclaim they deserve. Meanwhile, needy nothing is decorated with what we today would have to call 'celebrity'; faith and trust are rewarded with betrayal, and honours go to entirely the wrong people. The list goes on. Art is made tongue-tied by authority, and folly has an iron grip on genuine skill and actual accomplishment. And most telling of all: simple truth is wilfully misrepresented as 'simplicity'. The poem could have been written this morning, and virtually everything Shakespeare says in it would still be true. And therein lies another great revelation, or perhaps confirmation, of something we can know for practically certain: there is no such thing as 'the good old days'. Things four hundred years ago were exactly as bad as they are now, and in many respects they were a whole lot worse.

Nobody who is in a generally fairly gruntled place needs to let off steam like this. If we continue to assume, as we have been doing from the word go and for very good reasons which we stated early on in the Introduction – and as we have since had affirmed and indeed confirmed by the scholars we have spoken to, even those who take a sceptical view of reading the sonnets 'biographically' – that these sonnets are rooted in lived experience, that they are not mere theoretical writing exercises, but borne out of William Shakespeare's own life situations, then we must conclude from this sonnet that he is going through a rough patch.

This hardly comes as any great surprise: we have been getting the impression for a while now that our poet is deeply preoccupied with his own age, with the age difference between him and his lover, and with mortality and the passing of time generally, and now he presents us with as comprehensive – though hardly exhaustive – a list of items that drive him to distraction and despair as he can fit into fourteen lines.

This is not the poetry of a man who is being celebrated, who is seeing his work read and performed and sold and handsomely paid for, who is making a success of and name for himself in the world. This is the poetry of a man who would dearly wish all of these to be the case and yet finds himself disparaged by his peers while advancing in years, and still unable to get a foothold in his career.

And this means that in all but certainty Sonnet 66 has to have been composed before the end of 1594. Because from the end of 1594 onwards, things start to look up for Shakespeare. The theatres reopen after repeated closures because of the plague, and his troupe of actors becomes the Lord Chamberlain's Men. The Lord Chamberlain holds one of the highest offices at court, closest to the monarch, and so his patronage by definition means that as an actor and playwright you are doing well.

From late 1594, early 1595 onwards, Shakespeare's plays are regularly performed both at the theatre and at court, and with perhaps his principal direct competition, Christopher Marlowe, having been murdered on 30 May 1593, Shakespeare is now becoming the most performed playwright on the English stage. Not only that. Also in 1593, William Shakespeare's long narrative poem, Venus and Adonis, is published, followed in 1594 by The Rape of Lucrece, both of which he has dedicated to the young and exceptionally beautiful and unfathomably rich Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. They both become hits with readers and sell copies in their thousands, and so from late 1594 onwards, William Shakespeare really has no reason to rant. For several years thereafter he is doing wonderfully well, certainly economically and in terms of his status as a writer.

It won't be all plain sailing from thereon in: tragedy is about to strike with a profound impact on him when his eleven-year-old son Hamnet dies in August 1596, but that does not usually prompt a man to rant. It may make a man go into himself and find new depths to his understanding of human life and such meaning as it may have, but even then, the financial rewards and public recognition for his work keep pouring in, and so Sonnet 66 simply does not make sense post-1594. Ever really. Because no matter how difficult the relationship with his young lover becomes, no matter how much he will soon feel put upon by someone encroaching on his territory emotionally and also to some extent professionally, no matter how deeply the loss of his son and therefore heir and bearer of his name gets to him, the bulk of Sonnet 66 only shoulders the weight it does until mid to late 1594, which is, as it happens, soon after Shakespeare has turned thirty.

The sonnet could have been written, in theory, more or less any time before then, but again, we have to ask ourselves: would a young man, newly arrived in town, with everything to play for complain like that? It is really unlikely. I speak from some experience: I arrived in London as a 21-year old, exactly 400 years after Shakespeare left his native Stratford, and for the first few years you are far more likely to be wide-eyed and bushy-tailed than frustrated: you look for opportunities, you find them, you try to make something of them. You meet and associate with new people, you wonder at the multitudes, the cultures, the life. None of this would have been fundamentally different in Shakespeare's day.

Granted, he 'disappears' for seven years before he is mentioned in London. But in order for Robert Greene to take note of him, as he does, in 1592 as an 'upstart crow', Shakespeare has to have had some chance to draw attention to himself. And even if we allow – as we must – for fast-paced living in Elizabethan England, we can still relatively safely assume that Shakespeare arrives in London most likely no later than about 1590/91, aged around 24, 25.

If you have been listening to this podcast, you may remember that Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells in their edition of The Sonnets, which attempts to arrange them in what they themselves call a putative chronological order, following the dating method by Professor Macdonald P Jackson, place the group containing Sonnets 60-77 at just around that time: 1592-96. This on its own would tally with our understanding of the sonnets so far. Where their timing diverges is by putting this entire group before Sonnets 1-59, which for our and most people's understanding of the sonnets creates a massive problem, and we will examine this further when we get to the end of this group with Sonnet 77, which also, as it happens, marks the halfway point in the collection.

For the time-being, what we can say about Sonnet 66 – apart from the fact that it is clearly a singular piece of sonneteering that has virtually no equal in all of Shakespeare's output of the form – is that it gives us a great and unspun insight into William Shakespeare's whole state of being: not just his state of mind, but with a great deal of probability also his standing in the world and his perception of himself as a working writer. And this state of being is, once more, entirely congruent with the other sonnets that we find in its vicinity: the concern with age, the awareness of the passing of time, the wish and need to somehow immortalise his lover. All of this fits and makes sense.

As do the sonnets which are about to follow. Because what comes next is really quite the most extraordinary post-rant whinge at the ways of the world in terms of fashion and people's conduct, stretching over two poems, Sonnets 67 & 68, before, only for the second time in the series so far, William Shakespeare effectively admonishes his young lover, in Sonnet 69. He back-pedals fairly furiously in its companion piece, Sonnet 70, but all of these next ensuing sonnets are well within the tone and atmosphere and comparative mind-muddle that appertain to a man who is not, here and now, standing on what he once, in Sonnet 16 and in relation to his young lover, called "the top of happy hours," but of a man who is feeling put upon, who is sensing his days slip away, who worries about his love too being all to temporary, who realises that he maybe is expected but doesn't know how to nor want to keep up with the fast-changing times, and who has simply had enough of it all.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!