Sonnet 71: No Longer Mourn for Me When I Am Dead

|

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell Give warning to the world that I am fled From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell. Nay, if you read this line, remember not The hand that writ it, for I love you so That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot, If thinking on me then should make you woe. O if, I say, you look upon this verse, When I perhaps compounded am with clay, Do not so much as my poor name rehearse, But let your love even with my life decay, Lest the wise world should look into your moan And mock you with me after I am gone. |

|

No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell Give warning to the world that I am fled From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell. |

Do not mourn for me any longer than you can hear the sullen or sulky sound of the death bell tolling and announcing to the world that I have escaped from this horrible place to rest with most horrible worms.

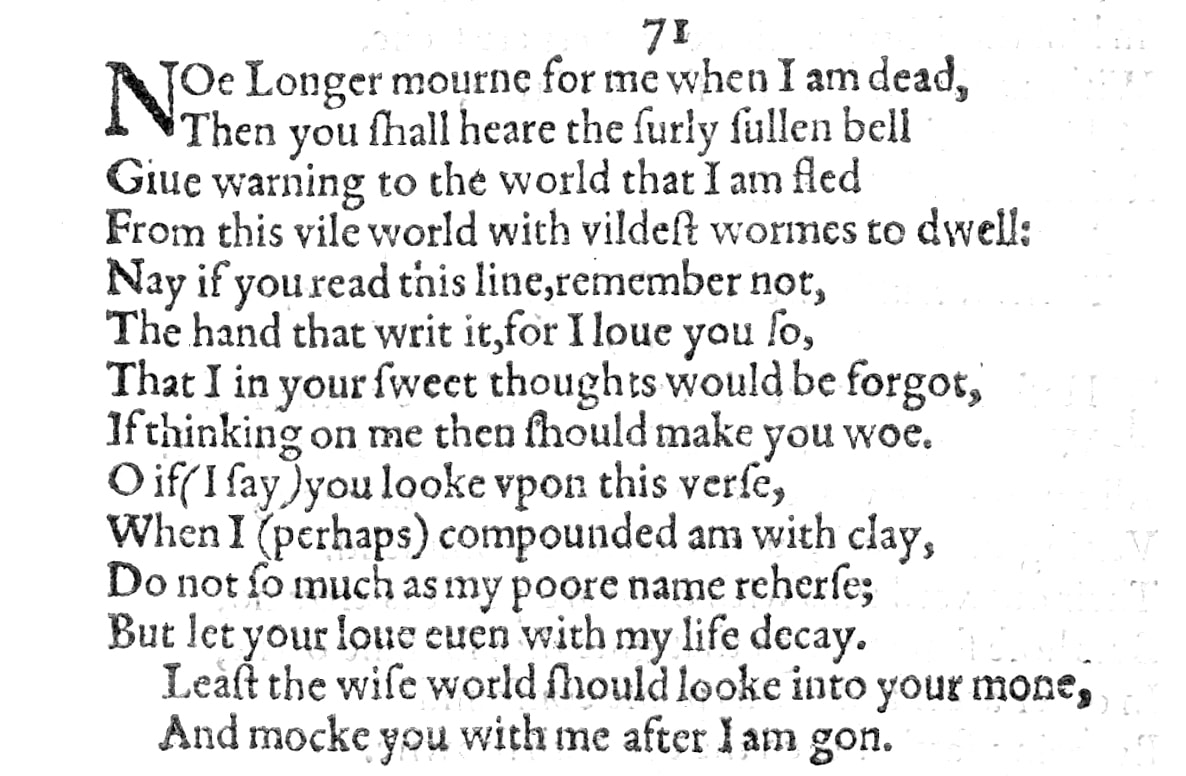

There is, as so often, something lost in the translation of this first quatrain, which manages to be both hauntingly evocative and yet, with its slightly over the top characterisation of the world as 'vile' and the worms with which we dwell once buried as 'vilest', also mildly ironic at the same time. The meaning of it is entirely clear, but its composition contains an additional layer which we can still sense even though contemporary spelling almost obliterates it. The Quarto Edition has: Noe Longer mourne for me when I am dead, Then you shall heare the surly sullen bell which subtly changes the dynamic, because it allows us to also read: No longer mourn for me when I am dead. Then, when I am dead, you will hear the surly sullen bell... And there is a difference, because the instruction not to mourn me when I am dead is much more categorical: a) don't do this, don't mourn me; and then, b) this will happen, you will hear the surly sullen bell. The spelling of 'then' and 'than' is interchangeable in Early Modern English and this is a glorious example of Shakespeare deploying the powers of his language to maximum and multiple effect. And the Quarto Edition also, incidentally, has the old spelling of vilest with a d: vildest. The 'surly sullen bell' we can imagine as either a death bell that is rung during a funeral procession as would have been the custom at the time, certainly in parts of England and Scotland, or indeed as the church bells tolling to announce a funeral, as still happens in many Christian congregations around the world. |

|

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot, If thinking on me then should make you woe. |

No, if you read this line, meaning of course this poem, then do not remember me – the hand which wrote it – because I love you so much and in such a way that I would rather be forgotten by you in your sweet loving thoughts, if thinking of me at that time should cause you pain or sorrow.

|

|

O if, I say, you look upon this verse,

When I perhaps compounded am with clay, |

What I am saying is that if you read or look at this verse that I have written for you, maybe at some time in the future when I am dead and my body has decomposed and returned to earth...

The 'perhaps' – which in the Quarto Edition, much as the 'I say' above is set in brackets – sits at a curious place in the line. It makes it sound as if there were a possible doubt over whether I, the poet, will at some point be 'compounded with clay'. But that, for any corpse, is at least a metaphorical certainty. If you bury a body in the ground it will over time become intermingled and amalgamated with the soil it has been laid to rest in. "Ashes to ashes," as the Bible has it, and "dust to dust." There may not be any great meaning attached to this odd positioning, but it adds to the deliberately heightened poetic, even ironic, tone of a poem that is actually really quite easy to understand, and in this stylistic choice there may well be contained some intent, as there may be in the choice of the word 'compounded' too, since that carries with it associations of things having gone from bad to worse. |

|

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love even with my life decay. |

...then, when you look at this poem, or indeed at this poetry more generally, of mine, do not so much as say or repeat my poor name, but let your love decay just as my life has decayed.

The understated and therefore paradoxical hyperbole continues: never mind about poor old me, just let your love rot, putrefy, and perish, much as I am doing when I'm dead. The choice of the word 'decay', of which these are all synonyms, for what the young man is supposed to allow his love to do is surely not accidental: Shakespeare is, quite obviously, making a point. And 'even' here, as so often, is pronounced with one syllable: e'en. |

|

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me after I am gone. |

So that when I am dead, the wise world does not look at your lament and mock you for it, in the way that it mocks me.

By now we feel tempted to put 'wise' into inverted commas, because it is hard to believe that Shakespeare, who at other times has been so sure of his writing, should really think of a world that mocks him as wise. Interesting also is the choice of 'moan' which, incidentally, here as in other instances, would in Shakespeare's pronunciation have had a perfect rhyme with 'gone'. In Sonnet 30, Shakespeare enjoys the sound of it so much, he not only talks about how he can "moan th'expense of many a vanished sight," but also tell over and over again "the sad account of fore-bemoaned moan," and in Sonnet 44 he talks of how, being away from his lover, he has to "attend time's leisure with my moan," so certainly within the Sonnets there is precedent for a gently ironic use of the word. |

Sonnet 71 is the first in a pair of poems which purport to urge the young man to forget the author after his death so as to spare him – the young man – any embarrassment or indeed mockery that having loved or still caring for the then deceased poet might cause him. Both sonnets, but Sonnet 71 in particular, strike an ironic tone, which nevertheless seems founded in an unease on Shakespeare's part about his own reputation and standing in the world. Sonnet 71 thus ushers in a short sequence consisting of this couple of sonnets and the following one, Sonnets 73 & 74, which all concern themselves with William Shakespeare's increasingly strong sense of his mortality and the question of what meaning his life may have in the context of his love for the young man.

As ever when we encounter a pair, we will be looking at Sonnets 71 & 72 together in the next episode, whilst concentrating on the first of the two, Sonnet 71 in this one.

It has been pointed out that with its number, Sonnet 71 sits at the position in the collection that corresponds to the first year beyond the biblical anticipated lifespan of a human being of 'three score year and ten', which is 70. Whether this is a quirky coincidence or in fact a deliberate act of curating on the part of whoever put the Quarto Edition of 1609 together, we cannot know. It is certainly a possibility – numerology, much as astrology, and symbolism generally – were much espoused at the time and many scholars consider it likely that at least some of these sonnets contain hidden references and meanings which to us are lost in the mists of time. But here this would be and would remain pure speculation.

We also, as we know and have discussed extensively before, cannot be sure that the sonnets are 'in the right place' in the collection, and strong arguments can and have been made – among others by Sir Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson on this podcast – that the collection as we have it does not form a coherent chronological sequence.

So it is interesting – although it may or may not be truly significant – that this new crisis of confidence in both Shakespeare's perception of his own status and the commitment he has from his young lover should come directly after the young lover himself has been through an apparent assault on his reputation and standing. Edmondson Wells, following the dating method of Macdonald P Jackson, keep Sonnets 61 to 77 together and in sequence, and certainly it seems clear throughout this phase which our poet is going through, that all is not especially well.

We have been in a similar place before: In Sonnet 36, which sits right in the middle of the big fallout from the young lover having had a thing or a fling with Shakespeare's mistress, and immediately after Shakespeare expressed his outrage at the young man's behaviour, he then either related or projected the reputational damage incurred by the young lover to or on himself:

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one,

So shall those blots that do with me remain

Without thy help by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite

Which, though it alter not love's sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight.

I may not ever more acknowledge thee

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me

Unless thou take that honour from thy name.

But do not so, I love thee in such sort

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

We ventured at the time that Sonnet 36 may have slipped out of sequence and in fact belong elsewhere, and it is equally possible that Sonnets 71 & 72 are in some way linked to these 'earlier' events, but considering the fairly turbulent existence of an Elizabethan playwright and poet and his most likely aristocratic young lover it is just as probable that we are here in a new chapter of their lives.

What the words themselves tell us is that there is a similarity between Sonnet 36 and Sonnet 71, in both the emotional turmoil and the strange mix of sincere self doubt and semi-serious self deprecation, laced with a perceptible taste of irony and a whiff of wishful thinking about the lover's investment in this relationship.

But here Shakespeare goes a step further than he did in Sonnet 36. It is one thing to tell your lover not to make a public show of their affection and to maintain an appearance of separation. Anyone who has been in a same-sex relationship before approximately 2004 and in way too many parts of the world still today would know that feeling: best not hold hands. Best not make a show of it. Best be discreet. People may be offended. Someone may attack you. There is a price to pay for a display of love. To be clear, Shakespeare's reasons for his anxiety in Sonnet 36 stem from a different source to what we today would call 'homophobia', and men showing some forms of affection to each other would have been considered fairly normal in Elizabethan England, but we can understand from recent and lived experience why someone would want to protect their lover from the consequences of being seen to be in love with you in public.

Sonnet 71 goes beyond that and Sonnet 72 will make this even clearer: what Shakespeare is suggesting here is that the young man should not only desist from public displays of affection or, as would be the case in light of bereavement, grief, but that he should forget about him altogether and not grieve his loss at all.

And that is what makes Sonnet 71 so revealing. Because this he can't possibly mean. And he makes it clear that he doesn't mean it by being blatantly – if perhaps mildly – ironic about it. And if you say to someone in irony that they should forget you, then what you are really telling them is that they should remember you. But why would you say that to someone you are sure of? You wouldn't. It would not make sense to, in fact it may well offend. Imagine telling the person whom you are in a deeply committed, long-lasting relationship with – maybe, for the sake of argument, your life partner of several years – 'please don't forget me when I'm gone'. They would think there's something wrong with you. Of course they won't forget you: you are part of their life. It is out of the question.

So why make a point of telling someone to let their love die with your own death, and mean the opposite? Because you love them but you can't be sure of how or how much they love you. That would be a good reason. It may not be wise, but it would make sense. But why, then, doesn't Shakespeare simply say so: why doesn't he just come out with it and write a poem that states: I love you with all my heart but I still, after all this time, don't know if you are feeling anywhere near the same about me as I do about you, but please just, when I'm no longer here, remember me.

Because we tend not to. Especially not when we're conflicted. Especially not when the person we love is really living on a different plane, sometimes apparently on a different planet; especially not if they are essentially out of our league and have made it clear beyond our own reasonable doubt that they can take us or leave us. That we have no right to them. That they do not need or want to be pinned down. That their status is one we do not share.

And also because we may not be as sure of ourselves as we'd like to be. Especially when the world mocks us. And we know the world mocks Shakespeare, we have it in writing, and we've quoted it before: at some point around about the time when these sonnets are being composed, Robert Greene's famous insult appears that labels our Will an 'upstart crow'. We talked about this in a bit of detail in the episode on Sonnet 25, and so I won't relate the whole story again now. And very soon the existential doubts that Shakespeare has will be compounded – not as in amalgamated with clay or anything else, but as in made considerably worse – because a rival poet is about to appear on the horizon, and if there is one thing you do not need as a writer in crisis if for another writer to come along and be better than you. Or more favoured. Or just altogether more successful.

I have said on one or two occasions and certainly in the Introduction that what makes these sonnets to riveting, so compelling, is how human they are. How timeless and therefore how, in a way, contemporary. This is life as it is lived, right here. It's complex, it's messy, it's unreasonable. It's difficult. And it's utterly wonderful.

How though can we be sure that the whole thing is not just a friendly joke between lovers. How can we say for certain that when it comes to feeling 'mocked', or, as we shall hear in Sonnet 72 'shamed', Shakespeare is being serious when he is being ironic about other things in the same two poems? There is a nuanced shift in tone both here and in Sonnet 72, which certainly sounds serious in comparison, but that may not be quite sufficient. We will have to then wait for Sonnets 73 & 74, because there the mood and the meaning really shift and settle to become really quite disconcertingly sincere.

As ever when we encounter a pair, we will be looking at Sonnets 71 & 72 together in the next episode, whilst concentrating on the first of the two, Sonnet 71 in this one.

It has been pointed out that with its number, Sonnet 71 sits at the position in the collection that corresponds to the first year beyond the biblical anticipated lifespan of a human being of 'three score year and ten', which is 70. Whether this is a quirky coincidence or in fact a deliberate act of curating on the part of whoever put the Quarto Edition of 1609 together, we cannot know. It is certainly a possibility – numerology, much as astrology, and symbolism generally – were much espoused at the time and many scholars consider it likely that at least some of these sonnets contain hidden references and meanings which to us are lost in the mists of time. But here this would be and would remain pure speculation.

We also, as we know and have discussed extensively before, cannot be sure that the sonnets are 'in the right place' in the collection, and strong arguments can and have been made – among others by Sir Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson on this podcast – that the collection as we have it does not form a coherent chronological sequence.

So it is interesting – although it may or may not be truly significant – that this new crisis of confidence in both Shakespeare's perception of his own status and the commitment he has from his young lover should come directly after the young lover himself has been through an apparent assault on his reputation and standing. Edmondson Wells, following the dating method of Macdonald P Jackson, keep Sonnets 61 to 77 together and in sequence, and certainly it seems clear throughout this phase which our poet is going through, that all is not especially well.

We have been in a similar place before: In Sonnet 36, which sits right in the middle of the big fallout from the young lover having had a thing or a fling with Shakespeare's mistress, and immediately after Shakespeare expressed his outrage at the young man's behaviour, he then either related or projected the reputational damage incurred by the young lover to or on himself:

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one,

So shall those blots that do with me remain

Without thy help by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite

Which, though it alter not love's sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight.

I may not ever more acknowledge thee

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me

Unless thou take that honour from thy name.

But do not so, I love thee in such sort

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

We ventured at the time that Sonnet 36 may have slipped out of sequence and in fact belong elsewhere, and it is equally possible that Sonnets 71 & 72 are in some way linked to these 'earlier' events, but considering the fairly turbulent existence of an Elizabethan playwright and poet and his most likely aristocratic young lover it is just as probable that we are here in a new chapter of their lives.

What the words themselves tell us is that there is a similarity between Sonnet 36 and Sonnet 71, in both the emotional turmoil and the strange mix of sincere self doubt and semi-serious self deprecation, laced with a perceptible taste of irony and a whiff of wishful thinking about the lover's investment in this relationship.

But here Shakespeare goes a step further than he did in Sonnet 36. It is one thing to tell your lover not to make a public show of their affection and to maintain an appearance of separation. Anyone who has been in a same-sex relationship before approximately 2004 and in way too many parts of the world still today would know that feeling: best not hold hands. Best not make a show of it. Best be discreet. People may be offended. Someone may attack you. There is a price to pay for a display of love. To be clear, Shakespeare's reasons for his anxiety in Sonnet 36 stem from a different source to what we today would call 'homophobia', and men showing some forms of affection to each other would have been considered fairly normal in Elizabethan England, but we can understand from recent and lived experience why someone would want to protect their lover from the consequences of being seen to be in love with you in public.

Sonnet 71 goes beyond that and Sonnet 72 will make this even clearer: what Shakespeare is suggesting here is that the young man should not only desist from public displays of affection or, as would be the case in light of bereavement, grief, but that he should forget about him altogether and not grieve his loss at all.

And that is what makes Sonnet 71 so revealing. Because this he can't possibly mean. And he makes it clear that he doesn't mean it by being blatantly – if perhaps mildly – ironic about it. And if you say to someone in irony that they should forget you, then what you are really telling them is that they should remember you. But why would you say that to someone you are sure of? You wouldn't. It would not make sense to, in fact it may well offend. Imagine telling the person whom you are in a deeply committed, long-lasting relationship with – maybe, for the sake of argument, your life partner of several years – 'please don't forget me when I'm gone'. They would think there's something wrong with you. Of course they won't forget you: you are part of their life. It is out of the question.

So why make a point of telling someone to let their love die with your own death, and mean the opposite? Because you love them but you can't be sure of how or how much they love you. That would be a good reason. It may not be wise, but it would make sense. But why, then, doesn't Shakespeare simply say so: why doesn't he just come out with it and write a poem that states: I love you with all my heart but I still, after all this time, don't know if you are feeling anywhere near the same about me as I do about you, but please just, when I'm no longer here, remember me.

Because we tend not to. Especially not when we're conflicted. Especially not when the person we love is really living on a different plane, sometimes apparently on a different planet; especially not if they are essentially out of our league and have made it clear beyond our own reasonable doubt that they can take us or leave us. That we have no right to them. That they do not need or want to be pinned down. That their status is one we do not share.

And also because we may not be as sure of ourselves as we'd like to be. Especially when the world mocks us. And we know the world mocks Shakespeare, we have it in writing, and we've quoted it before: at some point around about the time when these sonnets are being composed, Robert Greene's famous insult appears that labels our Will an 'upstart crow'. We talked about this in a bit of detail in the episode on Sonnet 25, and so I won't relate the whole story again now. And very soon the existential doubts that Shakespeare has will be compounded – not as in amalgamated with clay or anything else, but as in made considerably worse – because a rival poet is about to appear on the horizon, and if there is one thing you do not need as a writer in crisis if for another writer to come along and be better than you. Or more favoured. Or just altogether more successful.

I have said on one or two occasions and certainly in the Introduction that what makes these sonnets to riveting, so compelling, is how human they are. How timeless and therefore how, in a way, contemporary. This is life as it is lived, right here. It's complex, it's messy, it's unreasonable. It's difficult. And it's utterly wonderful.

How though can we be sure that the whole thing is not just a friendly joke between lovers. How can we say for certain that when it comes to feeling 'mocked', or, as we shall hear in Sonnet 72 'shamed', Shakespeare is being serious when he is being ironic about other things in the same two poems? There is a nuanced shift in tone both here and in Sonnet 72, which certainly sounds serious in comparison, but that may not be quite sufficient. We will have to then wait for Sonnets 73 & 74, because there the mood and the meaning really shift and settle to become really quite disconcertingly sincere.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!