Sonnet 41: Those Pretty Wrongs That Liberty Commits

|

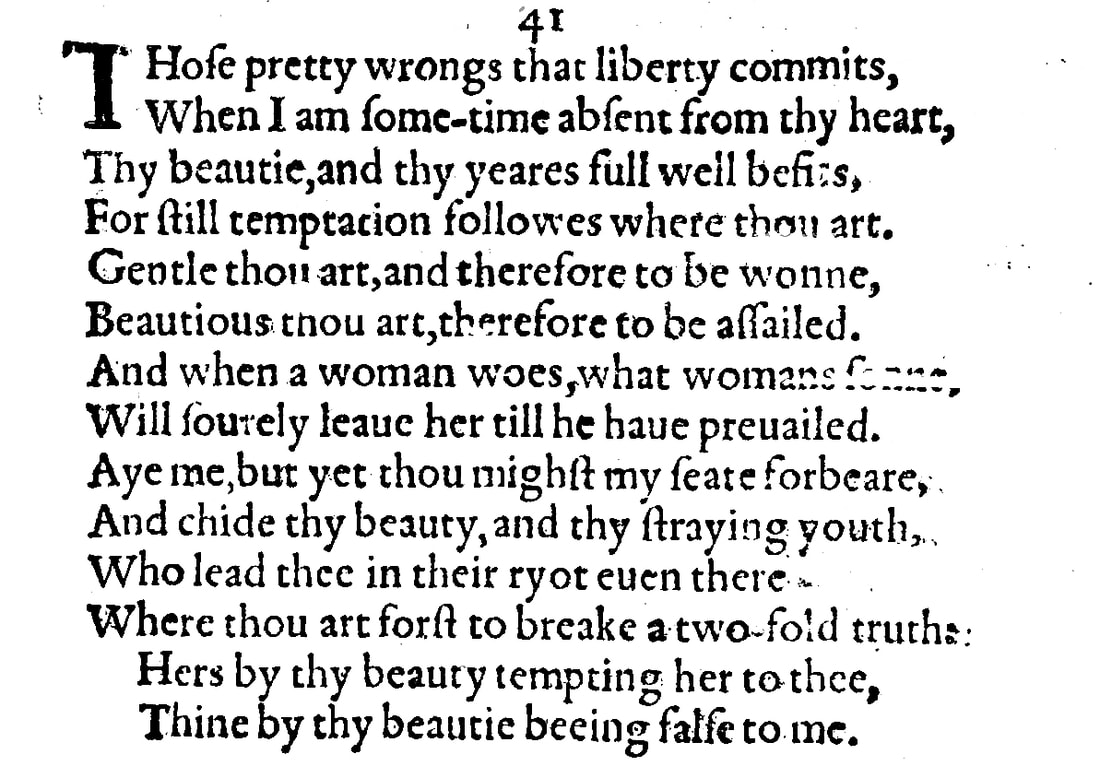

Those pretty wrongs that liberty commits,

When I am sometime absent from thy heart, Thy beauty and thy years full well befits, For still temptation follows where thou art: Gentle thou art, and therefore to be won, Beauteous thou art, therefore to be assailed, And when a woman woos, what woman's son Will sourly leave her till he have prevailed? Aye me, but yet thou mightst my seat forbear And chide thy beauty and thy straying youth, Who lead thee in their riot even there Where thou art forced to break a twofold truth: Hers, by thy beauty tempting her to thee, Thine, by thy beauty being false to me. |

|

Those pretty wrongs that liberty commits

When I am sometime absent from thy heart |

Those trifling little wrongs that your libertine or licentious behaviour commits when I am sometimes away from you and, it would seem, forgotten by you...

'Pretty' in Shakespearean English as today also of course means 'lovely', 'attractive' and, in an endearing way, 'beautiful', and many times before has Shakespeare told the young man that he is all these things, so there is most likely an ironic pun intended here. And while the proverb suggests that, in today's formulation, "absence makes the heart grow fonder," the occasions when I, the poet, am absent from your heart are times when your heart has in fact let go of me, or allowed me to slip from its enclosure, and that means you have at least temporarily forgotten about me. |

|

Thy beauty and thy years full well befits,

For still temptation follows where thou art. |

...these wrongs fully befit, meaning they are entirely congruent with, your beauty and your young years, meaning your youth, because obviously temptation always follows you around.

That this is 'obvious' is implied rather than stated, and strictly speaking, we would expect the verb 'befit' to be in the plural here, because Shakespeare is talking about wrongs in the plural, but it is not at all unusual for such minor discrepancies to occur at the time, and here 'befits' needs to rhyme with 'commits'. 'Still', here as elsewhere in Shakespeare, means 'always'. |

|

Gentle thou art, and therefore to be won,

|

You are gentle, and therefore an attractive and desirable 'prize' to be won.

There are two double meanings elegantly layered on top of each other here: you are, as I have often described you, a gentle person, meaning a kind, mild-mannered, highly civilised man, possibly also with a notion of possessing traditionally female qualities of gentleness, which would fit with the observation made in Sonnet 20 that you have a woman's features, a woman's eyes, and also a woman's gentle heart, and that you, as Sonnet 3 suggests, resemble your mother, and for all these qualities you are of course someone people find attractive. You are also a gentleman, though, meaning a man of noble birth and therefore high status, and this makes you a good catch for marriage. Which again carries a certain irony, since we know from Sonnets 1 - 17 how obstinate the young man has been in his refusal to marry. |

|

Beauteous thou art, therefore to be assailed,

|

You are beautiful and therefore an obvious target for seduction.

|

|

And when a woman woos, what woman's son

Will sourly leave her till he have prevailed? |

And when a woman woos a man, then what man would leave her pining for him until he had prevailed and she turned her attentions elsewhere?

Some editors emend the Quarto Edition for the line to read: Will sourly leave her till she have prevailed? This, however, does not really make sense: If the man who is being wooed by a woman leaves her until she prevails, then ultimately she succeeds in her wooing and he succumbs to her. This, as is clear from the rest of the sonnet, is exactly what the young man has done, so the rhetorical question – what man would do such a thing? – becomes meaningless. The ironic tone and deliberate reversal of traditional gender roles though continues, because it is absolutely the case that in Elizabethan England and right into the second half of the 20th Century it was really the man who wooed a woman, not usually the other way round. If a woman actively sought to seduce a man, she would traditionally either be considered a temptress or somebody offering sexual favours in return for compensation, or the language would be coached differently to make it clear that the signalling of a desire to marry – and that is what the wooing would have to be for in order for it to remain socially acceptable – is done in a virtuous, seemly, and above all virginal way. |

|

Aye me, but yet thou mightst my seat forbear

|

And yet you might resist that temptation and refuse to take my place...

'Aye me' is an expression of sadness or woe, a bit like 'alack!' or 'alas!' but more strongly focused on the speaker, while 'seat' here as elsewhere in Shakespeare is the rightful place of a person, indicating beyond doubt that Shakespeare makes a claim on the woman whom the young man has had a sexual encounter with: in other words, she is his mistress. |

|

And chide thy beauty and thy straying youth,

Who lead thee in their riot even there Where thou art forced to break a twofold truth: |

...and, instead of allowing yourself to be seduced, you might admonish your beauty and your straying youth, these two qualities of yours which – as if they were two riotous, boisterous, unruly lads – lead you into a situation where you are then forced to be unfaithful in two ways:...

'Truth' here as elsewhere means truthful and therefore faithful and also trustworthy in your behaviour, and is thus effectively synonymous with 'troth': a promise or pledge to loyalty and faithfulness, which indicates that as far as Shakespeare is concerned, both his mistress and the young man have either in words or in deed made such a pledge to him: in other words he expects both of them to be faithful to him Much as 'liberty' at the beginning of the sonnet, 'beauty' and 'straying youth' are here treated as if they were independent agents that the young man can and should to a greater or lesser extent control. But while the whole first quatrain absolves the young man from any wrongdoing, saying that the wrongs that his liberty commits are entirely in tune with his beauty and his years, meaning his youth, here now I, the poet, appear to have changed my mind, and I flag up the ways in which you yourself, by not exercising enough restraint over these qualities of yours, become responsible for two separate but interlinked betrayals: |

|

Hers, by thy beauty tempting her to thee,

Thine, by thy beauty being false to me. |

You are breaking her truth, for which read troth or pledge of faithfulness, to me by allowing your beauty to tempt her to you, and you break your own troth to me, by betraying me with her.

|

Sonnet 41 is the first of two sonnets in which William Shakespeare tries to make sense of the young man's transgression and to absolve him of any guilt. Like its companion Sonnet 42, it can be read independently and does not form an actual pair, and like Sonnet 42 it doesn't really succeed at what it sets out to do, because by the end of it, it is as clear to us as it is to William Shakespeare that both the young man and Shakespeare's mistress, with whom the young man has had a sexual encounter, have in effect betrayed our poet. What both Sonnet 41 and Sonnet 42 make abundantly clear and leave no doubt about is that this is exactly what has happened and that for William Shakespeare the most important thing now is to reassure himself as well as his young man that, as Sonnet 40 concludes: "we must not be foes," because clearly he cares too much for him than to let this peccadillo spell the end of their relationship.

The stark reality of loving someone who is much younger, from what we can tell very much more confident, and certainly almost infinitely richer than you is here heartfelt on display. And that this is a reality rather than a mere imagined scenario is something that we still can't in that sense prove but that is offering itself as a motivation for these sonnets more and more forcefully. We can imagine this: you are a writer of some growing success but without any real recognition as yet, you are married with a small family who live two days' ride away in Stratford-upon-Avon, you meet and become infatuated with this handsome, even beautiful, man who is essentially out of your league, and while you have been telling yourself and him for some time now that as far as you're concerned you two belong together, you have to realise that he, being so much younger and so obviously attractive to the world around him, will not be tied to you exclusively.

What makes this whole trio of Sonnets 40, 41, and 42 so fascinating though is not even really just this in its own way almost banal and predictable betrayal on the part of the young man, but the fact – and again that this is based in some sort of factuality seems impossible to reasonably argue with by now – that the betrayal, such as it is, has occurred with none other than with William Shakespeare's own mistress. And both, Sonnet 41 and Sonnet 42 are unequivocal in this.

Yet, in none of these sonnets does Shakespeare address the inherent question of whether his even having a mistress does in any way affect the extent to which it can be said that he is faithful to the young man. Let alone his wife Anne, of course. He will do so, but much later in the series. Going by the words in this sonnet alone, what we get is an abundantly clear picture of the young man and this mistress of Shakespeare's having sought or at any rate found opportunity to get it together, by the sounds of it while Shakespeare was away from them both, possibly out of town, on tour, as on occasion he was.

For William Shakespeare this presents a deep emotional conflict, for obvious reasons: if you love someone and you know deep in your heart that they can't and won't be yours alone forever, not least because there is no social framework in which such a relationship would be possible, but also because it may simply not be where the young man is at in his life and in his feelings towards you, and this person then does what in a way was to be expected and gets off with someone else, you have to somehow rationalise this behaviour, and you have to decide what it means to you. Whether you are going to let this be part of the compact, so to speak, that you both have other loves and lovers and your relationship is effectively an open one, or whether you insist on exclusivity at the risk of losing the person you love. Millions of couples face this kind of dilemma around the world today.

Shakespeare has made clear in Sonnet 40 already that the latter is not an option for him, that "we must not be foes," and so his therapeutic task – if we want to call it that – becomes one of accommodating the young man's liberties, which he clearly has taken and is therefore quite possibly prepared to take again, into the arrangement. This task is complicated enormously and for us in the most riveting fashion by the fact established by this sonnet: the young man's betrayal is a twofold one because it happened with the poet's own mistress and so caused her to betray him at the same time.

No wonder Shakespeare is unsure whom to blame. He starts off by saying: look, I totally understand, you are young and beautiful, it would be unreasonable of me or anyone to expect you not to be tempted now and then to have sex with someone you fancy and who fancies you. And this other person clearly plays a role in this: "when a woman woos" suggests that she has pursued you for this encounter as much if not more than you her, in fact in the words "till he have prevailed" contained is the notion that you may have held out against her advances for a while but quite understandably ultimately given in to her. Women can be wily like that, Shakespeare clearly feels and suggests.

But then, after these two quatrains which on their own do a decent job at absolving you of any actual wrongdoing, the turn in the argument: you really could have reined yourself in and, most particularly, you could and should have resisted taking my place. This – and it is again hardly surprising, because it is so obviously and roundly human – is what truly stings: that you went off with her, of all people, with my mistress. We may, from our perspective today, have mixed feelings about this possessive language coming from a man in relation to a woman whom he sees as having been taken by another man, but in the culture of the day this is entirely normal and standard: whether we think it right and the way it should have been or not, in Shakespeare's mind, his mistress is his, and, as he makes clear, the young man having a sexual fling with her amounts to a theft.

Sonnet 41 leaves it at that. It simply concludes with the observation that you, my young lover, have, by not being in control of the 'riotous' character embodied in your youth and your beauty, made yourself directly as well as indirectly responsible for a double betrayal. And there's little to argue about. If we take Shakespeare's perspective, and in a sense we have to, because we only have his side of the story through his carefully chosen words, then that's what this is: you have gone behind my back and betrayed me by having an affair, or at any rate a thing, with someone else, and you have compounded this by doing so with a woman who similarly and in the same act is betraying me because she is mine. It's easy to see why Shakespeare is upset. And that he is upset comes across astonishingly clearly in spite – or perhaps to some extent even because – of the way he tries, at least at first, not to show it.

As we noted at the end of Sonnet 40, we don't know who this woman is, and this sonnet gives us no clues either, other than that she is someone of whom Will thinks that she has made an explicit or implicit vow of fidelity to him. We also noted that there will be several sonnets in the much later Dark Lady sequence which will make it appear plausible that she is that same woman, but nothing in this Sonnet 41 here suggests as much, and so we simply have to wait and see how this story – such as it formulates itself both in Shakespeare's words and therefore over this stretch of the sonnets increasingly also in our minds – unfolds. And Sonnet 42 will lend a newly intriguing perspective with a fairly profound insight in its very own right...

The stark reality of loving someone who is much younger, from what we can tell very much more confident, and certainly almost infinitely richer than you is here heartfelt on display. And that this is a reality rather than a mere imagined scenario is something that we still can't in that sense prove but that is offering itself as a motivation for these sonnets more and more forcefully. We can imagine this: you are a writer of some growing success but without any real recognition as yet, you are married with a small family who live two days' ride away in Stratford-upon-Avon, you meet and become infatuated with this handsome, even beautiful, man who is essentially out of your league, and while you have been telling yourself and him for some time now that as far as you're concerned you two belong together, you have to realise that he, being so much younger and so obviously attractive to the world around him, will not be tied to you exclusively.

What makes this whole trio of Sonnets 40, 41, and 42 so fascinating though is not even really just this in its own way almost banal and predictable betrayal on the part of the young man, but the fact – and again that this is based in some sort of factuality seems impossible to reasonably argue with by now – that the betrayal, such as it is, has occurred with none other than with William Shakespeare's own mistress. And both, Sonnet 41 and Sonnet 42 are unequivocal in this.

Yet, in none of these sonnets does Shakespeare address the inherent question of whether his even having a mistress does in any way affect the extent to which it can be said that he is faithful to the young man. Let alone his wife Anne, of course. He will do so, but much later in the series. Going by the words in this sonnet alone, what we get is an abundantly clear picture of the young man and this mistress of Shakespeare's having sought or at any rate found opportunity to get it together, by the sounds of it while Shakespeare was away from them both, possibly out of town, on tour, as on occasion he was.

For William Shakespeare this presents a deep emotional conflict, for obvious reasons: if you love someone and you know deep in your heart that they can't and won't be yours alone forever, not least because there is no social framework in which such a relationship would be possible, but also because it may simply not be where the young man is at in his life and in his feelings towards you, and this person then does what in a way was to be expected and gets off with someone else, you have to somehow rationalise this behaviour, and you have to decide what it means to you. Whether you are going to let this be part of the compact, so to speak, that you both have other loves and lovers and your relationship is effectively an open one, or whether you insist on exclusivity at the risk of losing the person you love. Millions of couples face this kind of dilemma around the world today.

Shakespeare has made clear in Sonnet 40 already that the latter is not an option for him, that "we must not be foes," and so his therapeutic task – if we want to call it that – becomes one of accommodating the young man's liberties, which he clearly has taken and is therefore quite possibly prepared to take again, into the arrangement. This task is complicated enormously and for us in the most riveting fashion by the fact established by this sonnet: the young man's betrayal is a twofold one because it happened with the poet's own mistress and so caused her to betray him at the same time.

No wonder Shakespeare is unsure whom to blame. He starts off by saying: look, I totally understand, you are young and beautiful, it would be unreasonable of me or anyone to expect you not to be tempted now and then to have sex with someone you fancy and who fancies you. And this other person clearly plays a role in this: "when a woman woos" suggests that she has pursued you for this encounter as much if not more than you her, in fact in the words "till he have prevailed" contained is the notion that you may have held out against her advances for a while but quite understandably ultimately given in to her. Women can be wily like that, Shakespeare clearly feels and suggests.

But then, after these two quatrains which on their own do a decent job at absolving you of any actual wrongdoing, the turn in the argument: you really could have reined yourself in and, most particularly, you could and should have resisted taking my place. This – and it is again hardly surprising, because it is so obviously and roundly human – is what truly stings: that you went off with her, of all people, with my mistress. We may, from our perspective today, have mixed feelings about this possessive language coming from a man in relation to a woman whom he sees as having been taken by another man, but in the culture of the day this is entirely normal and standard: whether we think it right and the way it should have been or not, in Shakespeare's mind, his mistress is his, and, as he makes clear, the young man having a sexual fling with her amounts to a theft.

Sonnet 41 leaves it at that. It simply concludes with the observation that you, my young lover, have, by not being in control of the 'riotous' character embodied in your youth and your beauty, made yourself directly as well as indirectly responsible for a double betrayal. And there's little to argue about. If we take Shakespeare's perspective, and in a sense we have to, because we only have his side of the story through his carefully chosen words, then that's what this is: you have gone behind my back and betrayed me by having an affair, or at any rate a thing, with someone else, and you have compounded this by doing so with a woman who similarly and in the same act is betraying me because she is mine. It's easy to see why Shakespeare is upset. And that he is upset comes across astonishingly clearly in spite – or perhaps to some extent even because – of the way he tries, at least at first, not to show it.

As we noted at the end of Sonnet 40, we don't know who this woman is, and this sonnet gives us no clues either, other than that she is someone of whom Will thinks that she has made an explicit or implicit vow of fidelity to him. We also noted that there will be several sonnets in the much later Dark Lady sequence which will make it appear plausible that she is that same woman, but nothing in this Sonnet 41 here suggests as much, and so we simply have to wait and see how this story – such as it formulates itself both in Shakespeare's words and therefore over this stretch of the sonnets increasingly also in our minds – unfolds. And Sonnet 42 will lend a newly intriguing perspective with a fairly profound insight in its very own right...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!