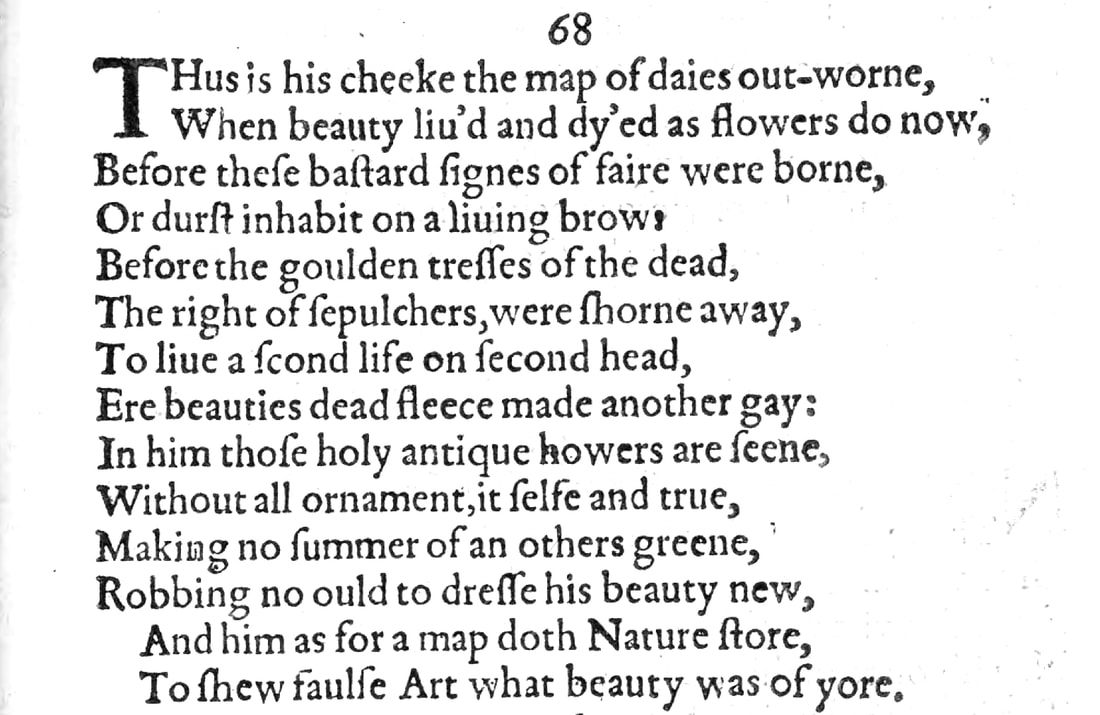

Sonnet 68: Thus Is His Cheek the Map of Days Outworn

|

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now, Before these bastard signs of fair were borne, Or durst inhabit on a living brow; Before the golden tresses of the dead, The right of sepulchres, were shorn away, To live a second life on second head, Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay: In him those holy antique hours are seen, Without all ornament, itself and true, Making no summer of another's green, Robbing no old to dress his beauty new; And him as for a map doth nature store To show false art what beauty was of yore. |

|

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

|

The sonnet continues from Sonnet 67 and obviously talks about the same person, Shakespeare's young lover:

Thus, in this way, his cheek, for which here as in Sonnet 67 and in many other instances read his face, is a record of the past... 'Map' extends its meaning here from being merely a 'record' of the past to also serve as a 'template' or 'plan' for the present and indeed the future, while the days of which Shakespeare speaks being 'outworn' suggests strongly that they are not only in the past, but also in a sense spent: they are worn out and exhausted and therefore irretrievably lost. It is interesting and certainly significant to note that not only does Shakespeare expand on the argument he set out in the previous sonnet, but does so very much in the dejected, tired tone of it too. |

|

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

|

...those outworn days of which my lover is the sole remaining example were the days when beauty lived and died as flowers still do today, meaning that they blossom when nature allows them to and then, having lived their life of beauty and delighted the world around them, they wither and die, as nature also intends and demands them to, in contrast to today where artificial means are employed to extend the ostensible life of beauty, with the result of course that this 'beauty' then is not real and pleasing but garish and fake.

|

|

Before these bastard signs of fair were borne,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow. |

Those outworn days, when beauty lived and died as flowers do now, were also a time before the bastardised appearance of beauty – such as it manifests itself in heavy make-up as described in the previous sonnet – were brought into the world or let alone would dare to inhabit and thus be present on a living face.

'Brow' as you will know if you've been listening to this podcast like 'cheek' appears repeatedly in these sonnets to mean 'face', and 'durst' is an old form of the past tense of dare. If we were still in any doubt about Shakespeare's attitude to make-up and artifice, then 'bastard signs of fair' should settle the matter once and for all: there is, as far as he is concerned, real, natural beauty, and there is artificial, fake 'beauty' that is therefore illegitimate and doesn't even deserve the name 'beauty'. Some editors emend the Quarto Edition's 'borne' to 'born', which modernises the spelling of a word that in Elizabethan English is treated as essentially the same, but it also diminishes the dual meaning of being 'born', as in having been given birth to, and being 'borne', as in being carried, being nurtured or cultivated. |

|

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchres, were shorn away, To live a second life on second head, |

It was also a time before the blonde locks of dead people, which rightfully belong to the grave and should therefore be left there on the dead body, were shorn away to be turned into a wig and thus live a second life on a second person's head.

Cutting off the hair of dead people to be used for wigs was a known and fairly common practice at the time, and 'golden', for which read blonde or strawberry blonde hair, was particularly prized. |

|

Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay:

|

It was a time before the precious golden hide, so to speak, of a genuine beauty was used to make somebody else appear gaudy or even garish.

'Dead fleece' is almost certainly a reference to the Golden Fleece sought and retrieved by Jason and the Argonauts in Greek mythology: the 'golden tresses' above plant in our minds the idea of 'golden' hair, and here this image is extended to the follicles that adorn beauty itself. 'Gay' is a problematic adjective for Shakespeare, and not for the reasons a 21st century person might expect. The general meaning of the word at the time is 'brightly coloured, showy'. It only, in the 19th century, acquires the meaning of 'carefree, light-hearted', which it retains for about a hundred years, before, in the mid-20th century, it comes to mean, as we mostly understand it today, 'sexually or romantically attracted to people of one's own sex' (Oxford Languages). Shakespeare uses the term eleven times only in his entire body of works. and for him something that is thus 'brightly coloured' and 'showy' has largely negative connotations, as is perhaps unsurprising considering how highly he values authenticity and things that are genuinely precious, and as we shall see again towards the end of the series in Sonnet 146. But to illustrate, in Othello, Iago answers Desdemona's question how he would describe a 'deserving woman' by saying: She that was ever fair and never proud, Had tongue at will and yet was never loud, Never lacked gold and yet went never gay, So the golden, albeit dead, fleece of beauty being used to make somebody else 'gay' is unquestionably a debasement of said fleece. |

|

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, itself and true, |

In him, my lover, the holy or sacred times of the past are still present and visible, without any ornament or embellishment or cosmetic artifice, but just as beauty is in its true self.

We would normally expect something to link 'those' to the description that follows, such as 'those holy antique hours are seen that are without any ornament', but this is here absent, and the 'itself' also has editors in different minds as to what exactly it refers to. Some point out, as John Kerrigan does, that "in Elizabethan English, plural expressions of time were sometimes treated as singular," others prefer reading it as referencing the young man, for whom it should then read 'himself', and in the context of the sonnet as a whole, it could also be understood as referring to the beauty of the young man itself. Although there may be no conclusive answer, the general thrust of the line is certainly clear enough. |

|

Making no summer of another's green

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new. |

And therefore he, my young lover, is not trying to create a second summer for himself by using another person's youthful hair as adornment or by robbing an erstwhile beautiful person who is now dead, which is why their beauty is old, to dress his own beauty as if it were new.

Although not explicitly stated, these couple of lines appear to draw attention to the fact that it is often of course old people whose natural youthful looks have gone who resort to make-up and, here specifically, wigs, to 'dress' their 'beauty new'. |

|

And him, as for a map, doth nature store,

To show false art what beauty was of yore. |

And him, my young lover, as stated in the first line to this sonnet, as well as in the previous sonnet, nature stores or keeps in store to be able to hold him up as an example and last remaining specimen of what beauty used to be, thus showing 'false art' for which here read the fake artifice of a manufactured 'beauty' just how poor and unworthy it is in comparison.

We can only guess what William Shakespeare would make of botox today... |

Sonnet 68 continues the argument from Sonnet 67 and shifts the focus of Shakespeare's opprobrium from the fashion for heavy make-up to that for wearing wigs, a practice by him equally abhorred. Unlike Sonnet 67, Sonnet 68 seems to be virtually devoid of any puns or double meanings that would resonate with us, and so although these two sonnets come as a closely linked pair in which the general note of dismay struck previously with Sonnet 66 continues to reverberate all the way through, Sonnet 68 nevertheless presents an entity of its own that in some respects appears to contrast, so as not to say contradict, Sonnet 67: if Sonnet 67 gave us an at least underlying sense of unease about the young man's own conduct, Sonnet 68 does nothing of the sort and simply holds him up as a flawless example of natural beauty.

Here are these two sonnets, as they belong, back to back:

Ah, wherefore with infection should he live

And with his presence grace impiety?

That sin by him advantage should achieve

And lace itself with his society?

Why should false painting imitate his cheek

And steal dead seeming of his living hue?

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek

Roses of shadow, since his rose is true?

Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins?

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And, proud of many, lives upon his gains.

O him she stores to show what wealth she had

In days long since, before these last so bad.

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

Before these bastard signs of fair were borne,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow;

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchres, were shorn away,

To live a second life on second head,

Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay:

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, itself and true,

Making no summer of another's green,

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new;

And him as for a map doth nature store

To show false art what beauty was of yore.

Taken together, Sonnets 67 & 68 come across as a pretty straightforward critique of the social mores of the day. The seeds of concern about the young man sown in Sonnet 67 do not gestate in Sonnet 68, and in fact Sonnet 68, if anything, nips any quibbles we may have believed to be wanting to grow in the bud.

Even if we accept, though, that maybe this is really what Shakespeare is here doing, add to his list of cavils with the world compiled in Sonnet 66 this pair with its heavy death-mask like make-up and its golden wigs, and assume no further issue with the young lover, we can't get away from the suspicion that there is something else at work underneath the surface. Because something we only observed almost in passing when discussing Sonnet 67 here comes up again and demands more of our attention. And that is the startling way in which all of the practices which Shakespeare here so berates apply to none other than the ruler of the day: Queen Elizabeth I.

Sonnets 67 & 68 clearly belong together and they are not just grouped with Sonnet 66, which sets the tone for this batch, and Sonnets 69 & 70 which very much tune into the same key even though they talk about something quite different, but they also sit thematically so close to Sonnet 66 that they may justifiably be considered to form an extension of it. Which is a slightly more complicated than necessary way of saying that Sonnets 67 & 68 very much seem part of a group that belongs together, of which Sonnet 66 marks the entry point.

We believe, as we saw when discussing it, to have strong reason to time the composition of Sonnet 66 no later than late 1594, but not much earlier either. By 1594, Queen Elizabeth I is 61 and her entire image is practically defined by heavy, deathly pale make-up and auburn wigs that in many portraits of the day look golden. And if you listened to the previous episode, you may recall that what prompts the queen to start wearing heavy make-up, apart, by now, from her age perhaps and her need for a timeless look, is an infection in 1562, at the age of 29, with smallpox. Smallpox – mercifully eradicated from our world since 1980 – was a horrendous viral disease that caused the death of some 30% of people who caught it and in many of those who survived left life-long scars. Elizabeth I succumbed to it for approximately two weeks and recovered, but her face bore the pockmarks for the rest of her days.

If, then, these lines invoke, or remind us of, anyone in the public eye in Shakespeare's day, it is the reigning monarch at the time when Shakespeare is writing these particular sonnets. And this gives rise to all manner of questions, none of which we can answer: is this a political commentary? Is Shakespeare using his young lover – of whom we know we don't know for certain who he is, but one of the strongest candidates for whom is a young nobleman who is extremely close to the queen – to indirectly have a dig at the queen?

If so, why? On grounds of aesthetics? There are theories, some of them not entirely without credibility, that Shakespeare was latently loyal to the catholic faith and, while never, as far as we can tell, drawing attention to himself as a recusant – which at any rate in his position as somebody seeking public recognition and royal approval would have been exceptionally brave or foolhardy or both – may have held misgivings against the protestant queen who, as we know and as he knew, dealt with the threat to her throne from adherents to the old faith with an unflinching rigour, which those at its receiving end may have experienced as religious persecution.

The sonnets were first published in the collection as we know them in 1609, six years after the queen's death, and, as it happens, some four years after the catholic-instigated Gunpowder Plot which sought to overthrow her successor, King James I, precisely for being, as she was, a protestant monarch. Before their publication, we noted, some sonnets were known to circulate among Shakespeare's 'private friends' as Frances Meres put it at the time, and so it is entirely possible, but not provable or provably knowable, that some poems which, if published at the time of their composition might have been highly contentious or even dangerous for their author, could have been written, read, and recited – maybe talked about, debated, even laughed about – in private by people who understood what they were about even if we today don't.

This may in fact be the principal or perhaps even the only conclusion we can draw from this in places highly perplexing group of sonnets: it could well be that they contain meanings we simply don't get, because we are not closely connected enough to the time and the conditions in which they were written. Equally though, it may be the case that we are tempted to read too much into them and that they have little or nothing to say beyond what we readily understand. It needn't surprise us if we find the latter of these 'scenarios' hard to swallow. Not only are we naturally inclined to look for meaning and therefore possibly find it where there is none, but we also know our poet as a master of layered composition. Time and again we have seen him pack multiple meanings into outwardly straightforward lines: were these all misinterpretations prompted by wishful thinking and longing for there to be more to these poems than meets the eye? That too is possible but also genuinely hard to believe and really, as on multiple occasions we have seen and discussed, refuted easily enough.

The joy of a puzzle though is in its power to flummox. And so – forever adhering to our approach of listening to the words and what the words themselves tell us – the one thing we can say about Sonnets 67 & 68 is that they make a well-matched but still decidedly odd couple and that they find themselves in quite the most appropriate company, because what follows is no less vexing in turn. Sonnets 69 & 70 also form a pair and one that is no less troubling if what we are after were allowed to be poetry that's to the point with a simple, signposted message.

With the couple that follows, William Shakespeare takes his mixing of messages to a level at which we can only marvel. Either that or fling our hands in the air in despair and exclaim: Will! What is all this about? But while we may not get a clear and categorical answer, what we will get, by and by over the sonnets that follow, is more and more of a sense for what our poet is going through and for just how deeply the trouble that ails him troubles and ails him.

Here are these two sonnets, as they belong, back to back:

Ah, wherefore with infection should he live

And with his presence grace impiety?

That sin by him advantage should achieve

And lace itself with his society?

Why should false painting imitate his cheek

And steal dead seeming of his living hue?

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek

Roses of shadow, since his rose is true?

Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins?

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And, proud of many, lives upon his gains.

O him she stores to show what wealth she had

In days long since, before these last so bad.

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

Before these bastard signs of fair were borne,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow;

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchres, were shorn away,

To live a second life on second head,

Ere beauty's dead fleece made another gay:

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, itself and true,

Making no summer of another's green,

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new;

And him as for a map doth nature store

To show false art what beauty was of yore.

Taken together, Sonnets 67 & 68 come across as a pretty straightforward critique of the social mores of the day. The seeds of concern about the young man sown in Sonnet 67 do not gestate in Sonnet 68, and in fact Sonnet 68, if anything, nips any quibbles we may have believed to be wanting to grow in the bud.

Even if we accept, though, that maybe this is really what Shakespeare is here doing, add to his list of cavils with the world compiled in Sonnet 66 this pair with its heavy death-mask like make-up and its golden wigs, and assume no further issue with the young lover, we can't get away from the suspicion that there is something else at work underneath the surface. Because something we only observed almost in passing when discussing Sonnet 67 here comes up again and demands more of our attention. And that is the startling way in which all of the practices which Shakespeare here so berates apply to none other than the ruler of the day: Queen Elizabeth I.

Sonnets 67 & 68 clearly belong together and they are not just grouped with Sonnet 66, which sets the tone for this batch, and Sonnets 69 & 70 which very much tune into the same key even though they talk about something quite different, but they also sit thematically so close to Sonnet 66 that they may justifiably be considered to form an extension of it. Which is a slightly more complicated than necessary way of saying that Sonnets 67 & 68 very much seem part of a group that belongs together, of which Sonnet 66 marks the entry point.

We believe, as we saw when discussing it, to have strong reason to time the composition of Sonnet 66 no later than late 1594, but not much earlier either. By 1594, Queen Elizabeth I is 61 and her entire image is practically defined by heavy, deathly pale make-up and auburn wigs that in many portraits of the day look golden. And if you listened to the previous episode, you may recall that what prompts the queen to start wearing heavy make-up, apart, by now, from her age perhaps and her need for a timeless look, is an infection in 1562, at the age of 29, with smallpox. Smallpox – mercifully eradicated from our world since 1980 – was a horrendous viral disease that caused the death of some 30% of people who caught it and in many of those who survived left life-long scars. Elizabeth I succumbed to it for approximately two weeks and recovered, but her face bore the pockmarks for the rest of her days.

If, then, these lines invoke, or remind us of, anyone in the public eye in Shakespeare's day, it is the reigning monarch at the time when Shakespeare is writing these particular sonnets. And this gives rise to all manner of questions, none of which we can answer: is this a political commentary? Is Shakespeare using his young lover – of whom we know we don't know for certain who he is, but one of the strongest candidates for whom is a young nobleman who is extremely close to the queen – to indirectly have a dig at the queen?

If so, why? On grounds of aesthetics? There are theories, some of them not entirely without credibility, that Shakespeare was latently loyal to the catholic faith and, while never, as far as we can tell, drawing attention to himself as a recusant – which at any rate in his position as somebody seeking public recognition and royal approval would have been exceptionally brave or foolhardy or both – may have held misgivings against the protestant queen who, as we know and as he knew, dealt with the threat to her throne from adherents to the old faith with an unflinching rigour, which those at its receiving end may have experienced as religious persecution.

The sonnets were first published in the collection as we know them in 1609, six years after the queen's death, and, as it happens, some four years after the catholic-instigated Gunpowder Plot which sought to overthrow her successor, King James I, precisely for being, as she was, a protestant monarch. Before their publication, we noted, some sonnets were known to circulate among Shakespeare's 'private friends' as Frances Meres put it at the time, and so it is entirely possible, but not provable or provably knowable, that some poems which, if published at the time of their composition might have been highly contentious or even dangerous for their author, could have been written, read, and recited – maybe talked about, debated, even laughed about – in private by people who understood what they were about even if we today don't.

This may in fact be the principal or perhaps even the only conclusion we can draw from this in places highly perplexing group of sonnets: it could well be that they contain meanings we simply don't get, because we are not closely connected enough to the time and the conditions in which they were written. Equally though, it may be the case that we are tempted to read too much into them and that they have little or nothing to say beyond what we readily understand. It needn't surprise us if we find the latter of these 'scenarios' hard to swallow. Not only are we naturally inclined to look for meaning and therefore possibly find it where there is none, but we also know our poet as a master of layered composition. Time and again we have seen him pack multiple meanings into outwardly straightforward lines: were these all misinterpretations prompted by wishful thinking and longing for there to be more to these poems than meets the eye? That too is possible but also genuinely hard to believe and really, as on multiple occasions we have seen and discussed, refuted easily enough.

The joy of a puzzle though is in its power to flummox. And so – forever adhering to our approach of listening to the words and what the words themselves tell us – the one thing we can say about Sonnets 67 & 68 is that they make a well-matched but still decidedly odd couple and that they find themselves in quite the most appropriate company, because what follows is no less vexing in turn. Sonnets 69 & 70 also form a pair and one that is no less troubling if what we are after were allowed to be poetry that's to the point with a simple, signposted message.

With the couple that follows, William Shakespeare takes his mixing of messages to a level at which we can only marvel. Either that or fling our hands in the air in despair and exclaim: Will! What is all this about? But while we may not get a clear and categorical answer, what we will get, by and by over the sonnets that follow, is more and more of a sense for what our poet is going through and for just how deeply the trouble that ails him troubles and ails him.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!