Sonnet 6: Then Let Not Winter's Ragged Hand Deface

|

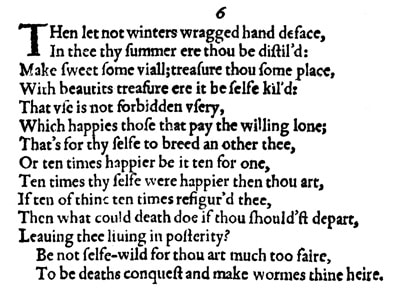

Then let not winter's ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer ere thou be distilled: Make sweet some vial, treasure thou some place With beauty's treasure, ere it be self-killed. That use is not forbidden usury Which happies those that pay the willing loan; That's for thyself to breed another thee, Or ten times happier be it ten for one. Ten times thyself were happier than thou art, If ten of thine ten times refigured thee, Then what could death do if thou shouldst depart, Leaving thee living in posterity? Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir. |

|

Then let not winter's ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer ere thou be distilled: |

Everything having been said in Sonnet 5 being the case — "then" meaning 'therefore' or 'so then' — do not allow the "ragged hand" of winter make your summer, and therefore by extension you, ugly before you yourself have been distilled, just like one of the flowers talked about in Sonnet 5.

"Deface" is a strong and immensely gratifying word to use here because not only does it reference the young man's beautiful face, of which we have heard several times now and will again shortly, but it also suggests something of a quite deliberate destruction: this Winter – in the Quarto on this occasion not capitalised – is not a pleasant character, and being the season of impoverishment, when, as we have seen, nothing blooms and everything is barren and bare, it would be clothed in rags; but 'ragged' here also has a meaning more akin to 'rugged', so Winter's hand may be imagined as wiry, grubby, but strong and quite rough. |

|

Make sweet some vial, treasure thou some place

With beauty's treasure, ere it be self-killed. |

And here is how it's done: take a metaphorical vial, a small container, and make it sweet with the distillation of yourself, much as a flower makes a glass vial sweet with its essence when it is distilled; or, put slightly differently, enrich some place with the treasure of your beauty, and do this before that beauty dies through its own doing, namely because it fails to have itself preserved somewhere.

The metaphorical vial into which a beautiful young man can put his distillation is of course a woman or, depending a bit on how graphically we want to imagine this, a woman's womb, and we have noted before the sexual overtones of the word 'treasure' in these early sonnets: William Shakespeare comes remarkably close to telling the young man not only to produce a child, but also how that is generally done. |

|

That use is not forbidden usury

|

We've also noted in Sonnet 4 that the idea of usury – the lending of money against interest, specifically against extortionate interest – is considered sinful in Shakespeare's day, and until very recently at that time also outlawed. In fact, it is made legal in 1571 under Elizabeth I, so approximately 20 years before Shakespeare writes this sonnet, and Shakespeare, like many of his contemporaries, still has a highly conflicted attitude to it.

Here he picks up on this again, and by implication on the suggestion made in Sonnet 4 that "Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend," and says that using your treasure to lend it to somebody is not unlawful... |

|

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

|

...if it makes those happy who "pay the willing loan."

In this case the person or people 'paying the loan' is or are either the woman who takes on the young man's beauty and 'pays it back' with the happy arrival of a beautiful child or several children, or it is the children themselves, or quite possibly both. The idea principally is that if you are happy to take on a loan and both able and pleased to pay it back with fair interest, then the person lending to you is not committing a sin: a loan is only problematic if the person who has to take it on does so against their will, because they are in dire straits and therefore prone to exploitation, but as we also already know from Sonnet 3: no woman in the world would "disdain" the young man's "husbandry," so the prospective mother's willingness and in fact pleasure at accepting this 'loan' is taken as read. And how wonderful a word "happies" is: it happies those that read it! (And it seems incomprehensible that we don't use 'to happy' as a transitive verb today.) |

|

That's for thyself to breed another thee,

|

This loan that we are talking about is of course not a monetary loan, it is a metaphor for what really needs to happen: you have to "breed another thee," namely a son...

|

|

Or ten times happier be it ten for one:

|

...or much better still: ten children. The happiness that ensues from making this loan will be tenfold if, rather than just one son, you have ten children.

Interesting side note here on interest: the legal rate that could be charged in Elizabethan England was 10%: one in ten. Shakespeare is clearly punning on this quite elaborately. (And what most credit card companies charge you in interest today would be considered outrageous, immoral and sinful in Shakespeare's day...) |

|

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

|

If you are one person and you are happy then ten people who are just like you – because they are your children – will increase the level of happiness in the world tenfold. And possibly also: you, by having a large family, will be ten times happier than you are now.

|

|

If ten of thine ten times refigured thee,

|

This would be the case if ten of your children made ten copies – one each – of yourself.

"Refigured" though can also apply forward, to mean if ten of your children made another ten children each who are themselves second copies of you. We are reminded of the abundance that Shakespeare referred to in Sonnets 1 and 4: by having children, not only the young man's beauty but also the happiness that he brings with his beauty will be prodigiously multiplied. And the playfulness of this whole passage has another facet to it: this part of the sentence sits applicable to both what went before and what comes next. You can say ten of you would make you happier than you are if ten of you represented or indeed made ten copies of you; but it can also be read as a new thought: if ten children of yours either ten times represented you, or indeed made ten versions each of you on top... |

|

Then what could death do if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity. |

...then what power would death have over you if you should die leaving behind the essence of yourself in your children for generations to come.

The conditional form here applies to the possibility of the young man having such offspring, not to the incidence of his death. Shakespeare is quite clear elsewhere that death is an absolute certainty, so we might expect him to say something like: "What can death do when thou shalt depart," but that is taken as read. What is open to potentially diverging outcomes is whether or not the young man will by then have left behind the children that allow him to continue "living in posterity." |

|

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine air. |

Don't be headstrong and obstinate and egotistical in your continued refusal to do as I suggest and have children, because you are much too beautiful to allow death to conquer you and to let the worms that will eat your body when your are buried to be the only beneficiaries of your thus much impoverished legacy.

|

Sonnet 6 continues the argument set up by Sonnet 5 and so the two really have to be taken together:

Those hours that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel.

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there,

Sap checked with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o'ersnowed and bareness everywhere.

Then, were not summer's distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft:

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was.

But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet

Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.

Then let not winter's ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer ere thou be distilled:

Make sweet some vial, treasure thou some place

With beauty's treasure, ere it be self-killed.

That use is not forbidden usury

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That's for thyself to breed another thee,

Or ten times happier be it ten for one.

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigured thee,

Then what could death do if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

These are the first two sonnets in the collection that come as a pair, and together they clearly continue to urge the young recipient of these sonnets to breed children. But there are two or three elements that are really quite noteworthy about them, apart from the fact that they come as a couple, which is in itself of course interesting: Shakespeare breaks the standard convention of the sonnet as a self-contained unit in which an argument is set up, explored, and concluded, and creates a bigger arc that spans over twice as many lines, giving him correspondingly much more scope for his elaboration.

While we are still to some extent in quite transactional territory – we still speak of usury, of loans, of legacy – the imagery that I, the poet, here conjure up is beginning to sound more involved, more imaginative, more poetic and more personal. There is no obvious knowable reason for this; we can not really speculate why this is the case, we can only observe it.

The analogy that I, the poet, invoke is that of a beautiful flower whose essence can be distilled and thus survive the deadly force of winter. Similarly, the young man can 'distil' himself and thus escape the ravages of death. The analogy, as happens now and then in Shakespeare, doesn't strictly work, because the distillation of a rose, for example, in a rosewater or a perfume, will only last as long as that substance is preserved, and once it's used up it is then gone, whereas a child will grow, live, and with a bit of luck produce further children and thus continue the young man's genes or essence for as long as the cycle of birth and death is unbroken.

But what makes these two sonnets particularly interesting is not their logical flaw — it is poetry after all, it works with imperfect imagery — it is really how they build and lead up the the closing couplet of Sonnet 6:

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

"Thou art much too fair." This is a change in tone. Up until now, I the poet, William Shakespeare, have spoken quite generally about "fairest creatures," and then moved on to talk about the young man's "beauty's field" — his face — and his youth's "proud livery," and beauty in fairly generic terms. In Sonnet 3, I made a very specific observation, namely that the young man is a mirror to and therefore mirror image of his mother, and this is certainly of great significance. But it is also something that I could know from hearsay or from looking at a picture of the young man and of his mother. In Sonnet 4, I called him an "unthrifty loveliness" and a "beauteous niggard," which still are terms that could, as we in fact have noted, be said about anyone of whom a few basic facts are known.

From Sonnet 5 we hear something confirmed we already had an inkling about: the young man's youth's "proud livery" was "so gazed on now" in Sonnet 2 and here in 5 we learn that "every eye doth dwell" on the "lovely gaze" of the young man: he is generally seen as beautiful.

Here now in Sonnet 6, I, the poet, say to the young man: "thou art much too fair" – and that's a subtle but noteworthy shift in tone. It's really the first time that I express an opinion that sounds as if it is mine own. A bit of distance has evaporated: I make an observation that could quite conceivably still be taken from a picture or imagined from hearsay, but it sounds more subjective than anything we've heard before. And as with most of these early nuances that we may note: we don't know if they mean anything. We don't know if they're intentional. We simply are able to register them.

And fortuitously, we get another little nugget in the exact same line: "be not self-willed." Now, it is entirely possible that no pun whatsoever is here intended. Also, the Quarto Edition spells this "self-wild" and so if this is how Shakespeare penned it, and not just how it was typeset, it may in fact pun on something entirely different. As we know though, spelling and typesetting are so inconsistent in Shakespeare's day as to be almost random. Furthermore, when looking at literary works like these, there is always a temptation to perhaps read more into lines than is actually there, to construct a narrative that suits us as the listeners or readers but that never even crossed the writer's mind. Still, William – Will – Shakespeare is a keen and proficient deployer of puns. Not least on his name. There will be plenty occasions when without doubt he puts his name into his sonnets.

Does he do so here? We don't know. Yet it is interesting that just as we sense that there is a subjective tone entering his writing for the young man here with this emphatic "thou art much too fair," we also get something that any intelligent mind would be quick to identify as the potential self-reference of a highly, intricately, skilled wordsmith. Coincidence? Possibly. Overthinking the matter? Not so much: Shakespeare composes these sonnets extremely carefully, and multiple layers are part of his panache. A hint that something may have shifted slightly in the relationship between the poet and the recipient of the poem? Very slightly, I would say, but quite conceivably yes...

Those hours that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel.

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there,

Sap checked with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o'ersnowed and bareness everywhere.

Then, were not summer's distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft:

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was.

But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet

Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.

Then let not winter's ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer ere thou be distilled:

Make sweet some vial, treasure thou some place

With beauty's treasure, ere it be self-killed.

That use is not forbidden usury

Which happies those that pay the willing loan;

That's for thyself to breed another thee,

Or ten times happier be it ten for one.

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigured thee,

Then what could death do if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

These are the first two sonnets in the collection that come as a pair, and together they clearly continue to urge the young recipient of these sonnets to breed children. But there are two or three elements that are really quite noteworthy about them, apart from the fact that they come as a couple, which is in itself of course interesting: Shakespeare breaks the standard convention of the sonnet as a self-contained unit in which an argument is set up, explored, and concluded, and creates a bigger arc that spans over twice as many lines, giving him correspondingly much more scope for his elaboration.

While we are still to some extent in quite transactional territory – we still speak of usury, of loans, of legacy – the imagery that I, the poet, here conjure up is beginning to sound more involved, more imaginative, more poetic and more personal. There is no obvious knowable reason for this; we can not really speculate why this is the case, we can only observe it.

The analogy that I, the poet, invoke is that of a beautiful flower whose essence can be distilled and thus survive the deadly force of winter. Similarly, the young man can 'distil' himself and thus escape the ravages of death. The analogy, as happens now and then in Shakespeare, doesn't strictly work, because the distillation of a rose, for example, in a rosewater or a perfume, will only last as long as that substance is preserved, and once it's used up it is then gone, whereas a child will grow, live, and with a bit of luck produce further children and thus continue the young man's genes or essence for as long as the cycle of birth and death is unbroken.

But what makes these two sonnets particularly interesting is not their logical flaw — it is poetry after all, it works with imperfect imagery — it is really how they build and lead up the the closing couplet of Sonnet 6:

Be not self-willed, for thou art much too fair

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

"Thou art much too fair." This is a change in tone. Up until now, I the poet, William Shakespeare, have spoken quite generally about "fairest creatures," and then moved on to talk about the young man's "beauty's field" — his face — and his youth's "proud livery," and beauty in fairly generic terms. In Sonnet 3, I made a very specific observation, namely that the young man is a mirror to and therefore mirror image of his mother, and this is certainly of great significance. But it is also something that I could know from hearsay or from looking at a picture of the young man and of his mother. In Sonnet 4, I called him an "unthrifty loveliness" and a "beauteous niggard," which still are terms that could, as we in fact have noted, be said about anyone of whom a few basic facts are known.

From Sonnet 5 we hear something confirmed we already had an inkling about: the young man's youth's "proud livery" was "so gazed on now" in Sonnet 2 and here in 5 we learn that "every eye doth dwell" on the "lovely gaze" of the young man: he is generally seen as beautiful.

Here now in Sonnet 6, I, the poet, say to the young man: "thou art much too fair" – and that's a subtle but noteworthy shift in tone. It's really the first time that I express an opinion that sounds as if it is mine own. A bit of distance has evaporated: I make an observation that could quite conceivably still be taken from a picture or imagined from hearsay, but it sounds more subjective than anything we've heard before. And as with most of these early nuances that we may note: we don't know if they mean anything. We don't know if they're intentional. We simply are able to register them.

And fortuitously, we get another little nugget in the exact same line: "be not self-willed." Now, it is entirely possible that no pun whatsoever is here intended. Also, the Quarto Edition spells this "self-wild" and so if this is how Shakespeare penned it, and not just how it was typeset, it may in fact pun on something entirely different. As we know though, spelling and typesetting are so inconsistent in Shakespeare's day as to be almost random. Furthermore, when looking at literary works like these, there is always a temptation to perhaps read more into lines than is actually there, to construct a narrative that suits us as the listeners or readers but that never even crossed the writer's mind. Still, William – Will – Shakespeare is a keen and proficient deployer of puns. Not least on his name. There will be plenty occasions when without doubt he puts his name into his sonnets.

Does he do so here? We don't know. Yet it is interesting that just as we sense that there is a subjective tone entering his writing for the young man here with this emphatic "thou art much too fair," we also get something that any intelligent mind would be quick to identify as the potential self-reference of a highly, intricately, skilled wordsmith. Coincidence? Possibly. Overthinking the matter? Not so much: Shakespeare composes these sonnets extremely carefully, and multiple layers are part of his panache. A hint that something may have shifted slightly in the relationship between the poet and the recipient of the poem? Very slightly, I would say, but quite conceivably yes...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!