Sonnet 25: Let Those Who Are in Favour With Their Stars

|

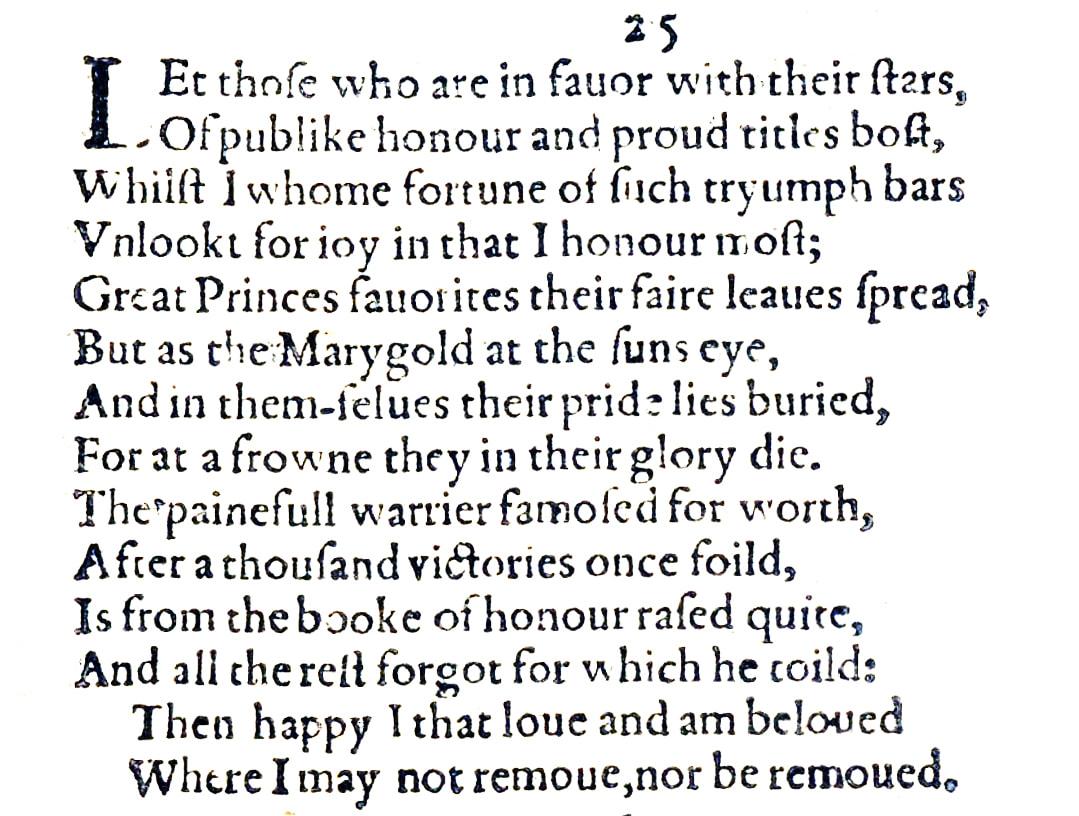

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast, Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars, Unlooked for joy in that I honour most. Great princes' favourites their fair leaves spread But as the marigold at the sun's eye, And in themselves their pride lies buried, For at a frown they in their glory die. The painful warrior, famoused for fight, After a thousand victories once foiled, Is from the book of honour razed quite And all the rest forgot for which he toiled. Then happy I that love and am beloved Where I may not remove nor be removed. |

|

Let those who are in favour with their stars

|

Let those people who are fortunate because the stars align themselves in such a way as to favour them; in other words, let those who are lucky by being successful...

|

|

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

|

...boast of the honours they receive and of the titles that are bestowed on them...

'Boast' in Shakespeare's day much as now suggests a lack of humility and an inflated sense of self-worth, and 'proud' as an adjective also has largely negative connotations, so William Shakespeare's attitude to those he is referring to is not one of unadulterated admiration, it would seem. |

|

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars,

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most. |

...while I, whose luck – or rather its evident absence or whose bad luck – keeps me from achieving such triumphs, and who I therefore remain unnoticed and unregarded by the establishment and the public, enjoy that which I honour most: namely you.

The fact that it is the young man whom Shakespeare delights in most is not spelt out here, but it is nevertheless beyond doubt and the final couplet will confirm this. |

|

Great princes' favourites their fair leaves spread

But as the marigold at the sun's eye, |

The favourites of great princes are like the marigold, a flower which opens its petals in the sunlight and closes them at night, in other words, they only bloom and come into their own for as long as this metaphorical sun – the prince – shines on them with his favours.

Virtually all powerful aristocrats at the time had their coterie of favourites around them, whom they advanced with titles, lands, gifts, money, patronage, often depending entirely on what was useful or politically expedient for them, and to receive favours in return, such as military or political support, or indeed, as several English and European kings did quite openly, sexual favours or simply the company and affection from their lovers. |

|

For in themselves their pride lies buried

And at a frown they in their glory die. |

Because the pride of these people is really hidden away in themselves, and as soon as the prince or patron frowns at them, for which read takes a dislike to them or voices some displeasure, their proud status and appearance goes away, again much as the marigold simply closes up and becomes meek and unassuming as soon as the sun disappears.

This was very much a reality of courtly life: the power of a king or a queen was such that they could end your career – in some cases end your life – more or less at a whim. |

|

The painful warrior, famoused for fight

|

The warrior who has both, been taking great pains to serve his commander, or his king or queen, or his country and who also through this has suffered great hardship and pain and is therefore 'painful', but who has acquired a great reputation for himself and is therefore also 'famoused'...

Note that 'famoused' is pronounced with three syllables: famousèd, whereas 'warrior' is pronounced with two syllables: war-rior. And there is a first proper textual issue here: the Quarto Edition of 1609 gives the line as: The painful warrior, famoused for worth Which practically all editors agree must be a mistake, since 'worth' simply doesn't rhyme with 'quite' as it will have to. Some propose 'might' as a credible substitute, mainly because it would a) make sense and b) the handwritten word 'might' might more easily be mistaken for 'worth' than the other obvious choice that offers itself and which is preferred here: 'fight'. 'Fight' is, after all, what a warrior does and what he – as he is referred to in this case – would therefore be justly famous for. Also it yields a satisfying alliteration, which is not something Shakespeare readily eschews elsewhere. |

|

After a thousand victories once foiled

Is from the book of honour razed quite |

Having so valiantly and painfully fought and achieved a thousand victories, all it takes is for the warrior to be foiled or beaten in battle once and he promptly gets stripped of all his recognition and honour...

Note that 'razed' is pronounced with two syllables: razèd. |

|

And all the rest forgot for which he toiled.

|

And everything he worked so hard for is forgotten, just like that.

|

|

Then happy I that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove nor be removed. |

Therefore I consider myself happy, because I love and I am also loved, and this in a place from which I may not go away nor may I be sent away, namely, and by implication, in your heart.

|

The at once defiant and celebratory Sonnet 25 is the first in the series to tell us something about William Shakespeare's own situation in life, and it also makes an astonishingly bold claim on the young man, newly asserting not only that the two of them belong together, but that they are inseparable.

After the insecurity of Sonnet 23 and the complexity and doubt of Sonnet 24, Sonnet 25 ends on a couplet that could scarcely be more emphatic:

Then happy I that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove nor be removed.

Going by these two lines alone, we could be forgiven for thinking that all is well again in the world of William Shakespeare and his young lover. Mutuality, reciprocity is restored. In Sonnet 22, I the poet, William Shakespeare, felt sure enough of our relationship to be able to say that my heart lives in your breast "as thine in me," and I told the young man about his heart: "thou gavest me thine, not to give back again."

Now, we cannot be certain of course that these specific sonnets were written in the order in which they were published any more than that the whole series was written in the published order, but even those scholars and editors who advocate reordering the collection and make educated attempts at doing so tend not to shuffle this group. And indeed, the sequence of this group makes sense as it stands.

So, for want of any good reason not to, let us accept them in the order in which we have them and note that from this blissful union and mutual exchange of hearts of Sonnet 22, we then underwent the wobble, so as not to quite call it a crisis, of Sonnets 23 and 24, only to find ourselves back on track here with the strongest expression yet we have from William Shakespeare that as far as he is concerned, the love he receives from the young man, and the commitment, is as strong and as binding as is his to the young man.

The question this naturally presents us with is of course once again: what has prompted this change of emotional weather? And while we don't know the answer to this, the most obvious and likely explanation – and remember that in the absence on certainty likelihood is our friend – is that since Sonnets 23 and 24, the young man has said or done or quite possibly himself written something that has reassured William Shakespeare, something that effectively amounts to: 'of course I love you: yes, I love you too', albeit most likely not in those precise words.

The reason this is such a plausible scenario is that – like so much of these sonnets and what is contained in them – it is so utterly human and almost disconcertingly normal: we meet, I fall in love with you, I express my adoration for you, I interpret whatever it is you do or say as you feeling the same about me, I say so, I get a confusing response or reaction, the messages I receive are suddenly mixed, I express my confusion and uncertainty, you do or say something to reassure me: "then happy I, that love and am beloved."

And maybe William Shakespeare should have just left it at that. Because it is one thing saying to someone: I love you and I know that you love me too. It is quite a different matter then adding: and I may never leave you nor may you leave me. But that is really for our next episode, when the fallout from what's just been said shall make itself known all too clearly.

Before then, though, we have to look at the rest of this Sonnet 25. And when I say 'the rest', I mean the bulk of it. Because eleven out of the twelve lines that make up the three quatrains of this sonnet do not talk about love, or about the loved one, or about the relationship at all. And, with that one exception, they tell us nothing about the young man at all. They tell us a lot about William Shakespeare.

The one line that forms the exception is the one that has the fragment "joy in that I honour most" in it. As we noted above, the young man isn't mentioned here, but it is obvious that this is whom Shakespeare is referring to. For the rest, Shakespeare here gives us a great insight into where he himself is at, not in relation to the young man, or as regards his love life, but in his professional life and as regards his social status. And while this is interesting in and of itself, it also yields up a clue as to when these sonnets are being written, which in turn will give us one more important pointer towards the likely identity of the young man.

From the sparse documentation and external evidence we have, we set the time frame for the composition of these sonnets to between about 1593 and 1603. By 1603, Shakespeare was a highly regarded, well established playwright. His name had started to appear on the title pages of his plays and people had started publishing them, often in unauthorised and highly flawed quarto editions, because his name sold copies. By about 1609, then aged 45, he had principally moved back to Stratford-upon-Avon, a wealthy man.

This Sonnet does not describe a poet who is about to 'retire' a highly respected and wealthy man:

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most.

William Shakespeare, at the time he writes this sonnet, is not in favour with his stars. He does not get any recognition. He cannot boast of public honours or proud titles. He is being ignored. This is very much the voice of a man who is frustrated with how things are going. Yes, I can "joy in that I honour most," but there is no doubt that I feel somewhat hard done by. In 1593, William Shakespeare was 29 years old, approaching 30. Not, by our standards, anything that resembles old age, but as we have seen, in Shakespeare's day, people age quickly. And by that time, he wasn't famous.

He had only recently arrived in London, and started to work as an actor and playwright there, and indeed, his plays were quite successful, but that gave him no status. We, today, see William Shakespeare as the paragon of the English language and the English theatre which he in no small measure helped elevate to an art form as a great exponent of our civilisation. In Shakespeare's day, people flocked to the theatre in their thousands but in their majority they didn't know who wrote these plays. The theatre was enormously influential and attracted large proportions of the London population, but Shakespeare was not being taken seriously as a playwright early on in his career.

There is the famous rant by the dramatist and pamphleteer Robert Greene who, himself aged only 34, died in 1592, so not long after Shakespeare's arrival in London. Just over two weeks after Greene's death, a pamphlet appeared which is almost universally believed to have been written by him, in which he says:

"... there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger's heart wrapped in a Player's hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country."

It's a jibe at Shakespeare, too thinly disguised to be doubted. He calls Shakespeare a jack of all trades – a 'Johannes factotum" – who, although not university educated, presumes to be able to write as well as any of the established authors who are collectively known as the 'university wits', and who include Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and Greene himself.

And lo! it all makes sense: you arrive in town, you try to make it as a poet and playwright, you get your plays put on and they go down well with the audiences, but your 'peers' don't accept you or take you seriously. You don't have a patron, you don't have a name, you don't get any recognition, you are short of money, and you're about to hit thirty. To understand just how pressing and depressing that is, you have to imagine yourself as a writer or musician or film director or games designer today pushing fifty. You're halfway through your life and you haven't made it. Not only that, the people who have made it actively disparage you.

That is the situation that William Shakespeare is in, and this Sonnet is the first, but certainly not the last one to tell us so. An even more famous one lies just around the corner, and it will spell this out for us even more clearly. But for the moment and for Sonnet 25, suffice it now to say: we get a clear and deep insight into the state of mind, the professional standing and the perception of his own status from our poet William Shakespeare, and what keeps him going, what lifts his spirits, what at any rate prompts him to sonnetise or to sonneteer, is his young man.

And this young man is not to be taken for granted. He is about to bring our poet crashing down to the earth in spectacular fashion...

After the insecurity of Sonnet 23 and the complexity and doubt of Sonnet 24, Sonnet 25 ends on a couplet that could scarcely be more emphatic:

Then happy I that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove nor be removed.

Going by these two lines alone, we could be forgiven for thinking that all is well again in the world of William Shakespeare and his young lover. Mutuality, reciprocity is restored. In Sonnet 22, I the poet, William Shakespeare, felt sure enough of our relationship to be able to say that my heart lives in your breast "as thine in me," and I told the young man about his heart: "thou gavest me thine, not to give back again."

Now, we cannot be certain of course that these specific sonnets were written in the order in which they were published any more than that the whole series was written in the published order, but even those scholars and editors who advocate reordering the collection and make educated attempts at doing so tend not to shuffle this group. And indeed, the sequence of this group makes sense as it stands.

So, for want of any good reason not to, let us accept them in the order in which we have them and note that from this blissful union and mutual exchange of hearts of Sonnet 22, we then underwent the wobble, so as not to quite call it a crisis, of Sonnets 23 and 24, only to find ourselves back on track here with the strongest expression yet we have from William Shakespeare that as far as he is concerned, the love he receives from the young man, and the commitment, is as strong and as binding as is his to the young man.

The question this naturally presents us with is of course once again: what has prompted this change of emotional weather? And while we don't know the answer to this, the most obvious and likely explanation – and remember that in the absence on certainty likelihood is our friend – is that since Sonnets 23 and 24, the young man has said or done or quite possibly himself written something that has reassured William Shakespeare, something that effectively amounts to: 'of course I love you: yes, I love you too', albeit most likely not in those precise words.

The reason this is such a plausible scenario is that – like so much of these sonnets and what is contained in them – it is so utterly human and almost disconcertingly normal: we meet, I fall in love with you, I express my adoration for you, I interpret whatever it is you do or say as you feeling the same about me, I say so, I get a confusing response or reaction, the messages I receive are suddenly mixed, I express my confusion and uncertainty, you do or say something to reassure me: "then happy I, that love and am beloved."

And maybe William Shakespeare should have just left it at that. Because it is one thing saying to someone: I love you and I know that you love me too. It is quite a different matter then adding: and I may never leave you nor may you leave me. But that is really for our next episode, when the fallout from what's just been said shall make itself known all too clearly.

Before then, though, we have to look at the rest of this Sonnet 25. And when I say 'the rest', I mean the bulk of it. Because eleven out of the twelve lines that make up the three quatrains of this sonnet do not talk about love, or about the loved one, or about the relationship at all. And, with that one exception, they tell us nothing about the young man at all. They tell us a lot about William Shakespeare.

The one line that forms the exception is the one that has the fragment "joy in that I honour most" in it. As we noted above, the young man isn't mentioned here, but it is obvious that this is whom Shakespeare is referring to. For the rest, Shakespeare here gives us a great insight into where he himself is at, not in relation to the young man, or as regards his love life, but in his professional life and as regards his social status. And while this is interesting in and of itself, it also yields up a clue as to when these sonnets are being written, which in turn will give us one more important pointer towards the likely identity of the young man.

From the sparse documentation and external evidence we have, we set the time frame for the composition of these sonnets to between about 1593 and 1603. By 1603, Shakespeare was a highly regarded, well established playwright. His name had started to appear on the title pages of his plays and people had started publishing them, often in unauthorised and highly flawed quarto editions, because his name sold copies. By about 1609, then aged 45, he had principally moved back to Stratford-upon-Avon, a wealthy man.

This Sonnet does not describe a poet who is about to 'retire' a highly respected and wealthy man:

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most.

William Shakespeare, at the time he writes this sonnet, is not in favour with his stars. He does not get any recognition. He cannot boast of public honours or proud titles. He is being ignored. This is very much the voice of a man who is frustrated with how things are going. Yes, I can "joy in that I honour most," but there is no doubt that I feel somewhat hard done by. In 1593, William Shakespeare was 29 years old, approaching 30. Not, by our standards, anything that resembles old age, but as we have seen, in Shakespeare's day, people age quickly. And by that time, he wasn't famous.

He had only recently arrived in London, and started to work as an actor and playwright there, and indeed, his plays were quite successful, but that gave him no status. We, today, see William Shakespeare as the paragon of the English language and the English theatre which he in no small measure helped elevate to an art form as a great exponent of our civilisation. In Shakespeare's day, people flocked to the theatre in their thousands but in their majority they didn't know who wrote these plays. The theatre was enormously influential and attracted large proportions of the London population, but Shakespeare was not being taken seriously as a playwright early on in his career.

There is the famous rant by the dramatist and pamphleteer Robert Greene who, himself aged only 34, died in 1592, so not long after Shakespeare's arrival in London. Just over two weeks after Greene's death, a pamphlet appeared which is almost universally believed to have been written by him, in which he says:

"... there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger's heart wrapped in a Player's hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country."

It's a jibe at Shakespeare, too thinly disguised to be doubted. He calls Shakespeare a jack of all trades – a 'Johannes factotum" – who, although not university educated, presumes to be able to write as well as any of the established authors who are collectively known as the 'university wits', and who include Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and Greene himself.

And lo! it all makes sense: you arrive in town, you try to make it as a poet and playwright, you get your plays put on and they go down well with the audiences, but your 'peers' don't accept you or take you seriously. You don't have a patron, you don't have a name, you don't get any recognition, you are short of money, and you're about to hit thirty. To understand just how pressing and depressing that is, you have to imagine yourself as a writer or musician or film director or games designer today pushing fifty. You're halfway through your life and you haven't made it. Not only that, the people who have made it actively disparage you.

That is the situation that William Shakespeare is in, and this Sonnet is the first, but certainly not the last one to tell us so. An even more famous one lies just around the corner, and it will spell this out for us even more clearly. But for the moment and for Sonnet 25, suffice it now to say: we get a clear and deep insight into the state of mind, the professional standing and the perception of his own status from our poet William Shakespeare, and what keeps him going, what lifts his spirits, what at any rate prompts him to sonnetise or to sonneteer, is his young man.

And this young man is not to be taken for granted. He is about to bring our poet crashing down to the earth in spectacular fashion...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!