Sonnet 77: Thy Glass Will Show Thee How Thy Beauties Wear

|

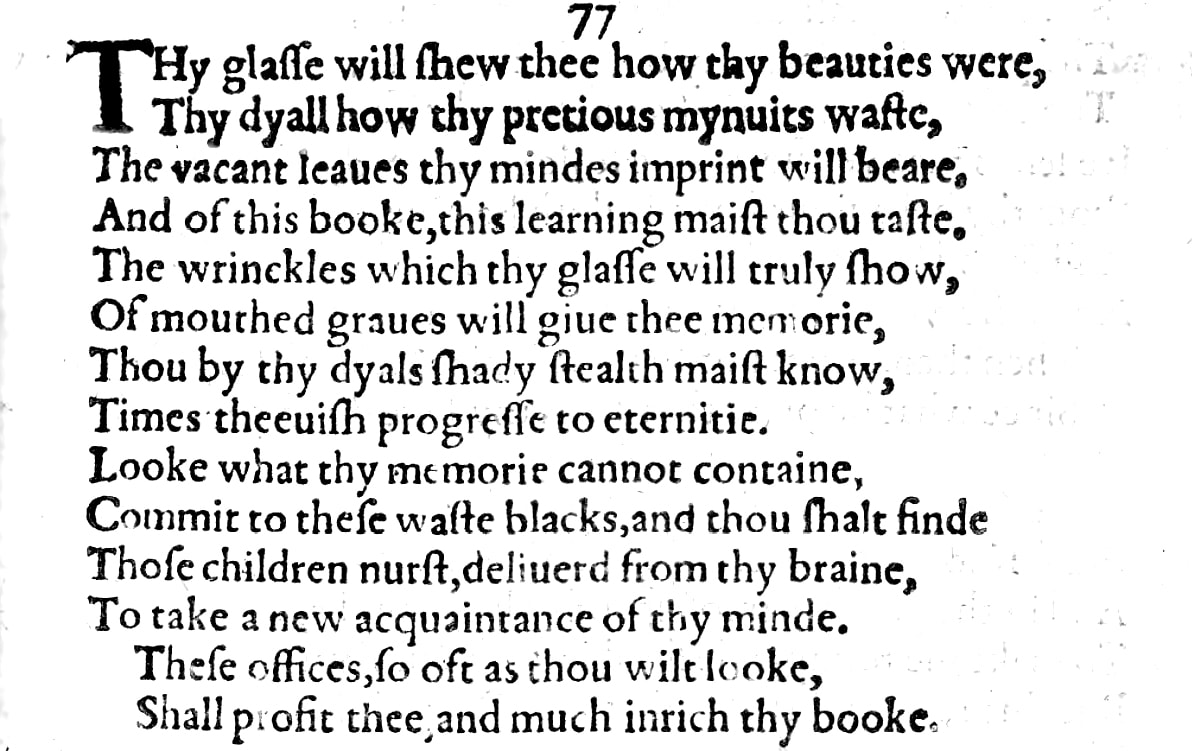

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear,

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste; The vacant leaves thy mind's imprint will bear, And of this book, this learning mayst thou taste: The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show Of mouthed graves will give thee memory, Thou by thy dial's shady stealth mayst know Time's thievish progress to eternity; Look what thy memory cannot contain, Commit to these waste blanks and thou shalt find Those children nursed, delivered from thy brain, To take a new acquaintance of thy mind. These offices, so oft as thou wilt look Shall profit thee and much enrich thy book. |

|

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear,

|

The sonnet talks to the recipient about an unspecified time in the future and says your mirror will show you how your beauty will wear off or wear out over time...

Editors note that in the Quarto Edition, the word 'wear' is spelt 'were' and speculate whether an additional meaning is intended of the mirror prompting the young man to reflect on what his beauties were once upon a time. This cannot be entirely ruled out, but it strikes me as comparatively unlikely. Spelling in Shakespeare's day is haphazard for many different reasons which we discussed a bit in the Introduction, so here, perhaps unusually, I am inclined to accept the common emendation to 'wear' without seeking any further layering. |

|

Thy dial how thy precious minutes waste;

|

...and your clock, or here more specifically your sundial, will show you how your precious minutes waste away as time passes.

The reason the time piece here referred to is most likely a sundial, if but for metaphorical or symbolic purposes, is that further down in the sonnet its progression is described as a 'shady stealth', which suggests the shadow of a gnomon creeping across the dial. |

|

The vacant leaves thy mind's imprint will bear,

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste: |

The empty pages – vacant leaves – of a notebook will carry your thoughts – your mind's imprint – and from this book here which I give you now, a book that you yourself will fill with your collected quotes and notes and thoughts, you may then sample or savour or enjoy the following learning.

While it is all but obvious that the second of these two lines refers to a book that William Shakespeare is either writing this sonnet into, perhaps on the first page as a dedication, or that he appends his sonnet to as an accompanying note or letter, what is not entirely clear is whether 'the vacant leaves' of the first of these two lines refers to the blank pages in this particular book, or to the blank pages that an educated young person would ordinarily use to take notes generally. Both are possible. Let us assume for the time-being that this sonnet too is addressed to Shakespeare's young lover, although this happens to be one of very few sonnets in the Fair Youth series that could in fact have been written for somebody completely different, and we shall look at this possibility shortly, and so Shakespeare is either saying to his young man that his notebooks will be the keepers of his thoughts quite generally and that what follows is now specific to this particular book of empty pages, or he is anticipating the introduction of the gift that follows immediately after. The difference is comparatively minor and does not alter the overall meaning of the sonnet. |

|

The wrinkles which thy glass will truly show

Of mouthed graves will give thee memory, |

Here we would expect Shakespeare to spell out the learning that this particular book can convey, but in fact he recapitulates what he's already told his reader, albeit here in quite unusual terms:

The wrinkles on your face which your mirror will show you truthfully or honestly in years to come will remind you of gaping graves and thus of your own mortality. It is a stark image, this, the mouthed graves, and there is no obvious explanation as to what prompts this in Shakespeare at this particular juncture. |

|

Thou by thy dial's shady stealth mayst know

Time's thievish progress to eternity; |

And by the stealthy advance of your dial you will see and understand the continuous progression of time towards eternity.

The idea that time is a thief – of beauty, of riches, ultimately of life – is fairly commonplace in itself, and we also are familiar with the notion of time 'creeping' or moving stealthily, meaning unnoticed, like a thief in the night. |

|

Look what thy memory can not contain,

Commit to these waste blanks and thou shalt find |

Whatever you cannot keep in your memory, commit it to these blank pages by writing it down, and you will find...

The Quarto Edition here has 'these waste blacks' but that does not make any sense at all, and so the emendation to 'blanks', which corresponds to the 'vacant leaves' earlier, is generally accepted as valid. |

|

Those children nursed, delivered from thy brain,

To take a new acquaintance of thy mind. |

...that these notes and thoughts that you are consigning to your book are like children which, by being kept and looked after there, outside of your brain, are being nursed until, at some point in the future, they can make a new acquaintance of your mind, meaning you can retrieve them and newly understand and work with them, as they will have matured with time, reflection, and education, much in the way you yourself will have matured by the same means.

|

|

These offices, so oft as thou wilt look,

Shall profit thee, and much enrich thy book. |

These caring duties – the keeping and nursing of thoughts in your notebook – will then benefit you every time you look at them and they will greatly enrich and improve your own writing.

The use of the word 'offices' strongly alludes to religious practice. In the context of the Christian church, Oxford Languages defines 'offices' as: "the series of services of prayers and psalms said (or chanted) daily by Catholic priests, members of religious orders, and other clergy." Shakespeare would no doubt have been aware of this and he appears to infuse his counsel here with a spiritual, even moral purpose. |

The curiously didactic Sonnet 77 marks the halfway point of the collection of 154 sonnets contained in the 1609 Quarto Edition and it stands out for several reasons. What most immediately catches the eye is that it seems to be written into or so as to accompany a book of empty pages for its recipient to collect their thoughts and notes in a book of commonplaces, as would have been widely in use at the time. And owing to its tone, it does pose the question whether it is in fact addressed to the same young man as the other sonnets in this large group known as the Fair Youth Sonnets, and if it is, whether it finds itself sequentially in the right place.

Colin Burrow in the Oxford Edition of The Sonnets credits the 18th Century Shakespeare commentator George Steevens with first suggesting that this sonnet was written to accompany a notebook, and it is an attractive conclusion that makes sense, drawn from the line

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste

which clearly appears to refer to the book the reader holds in their hand at that moment. It is also possible, but seems signally less likely, that either, a) Shakespeare means 'that book', referring to the vacant leaves in a notebook the reader is expected to use generally, or b), that he in fact wrote 'that book', but the typesetter made a mistake or erroneously corrected him. But these two considerations, in view of the convincing probability of the Steevens theory, do appear purely academic, and I am noting them here mostly to signal that, as in almost everything concerning these sonnets, we are still talking about degrees of likelihood rather than absolute certainties.

Assuming then that this is so and that the sonnet does accompany a gift, the two most obvious questions to pursue are:

1: Who is this gift for? Is it our young man or could this be a sonnet that has slipped into the collection even though it is actually addressed to somebody completely different?

2: What's the occasion? What prompts Shakespeare to give this person such a book, together with a specially composed sonnet?

And the two are of course connected, with the latter perhaps being the more trivial one, since there are any number of reasons that offer themselves, contingent somewhat on how we are inclined to answer the first.

Two indicators point at a recipient that matches our young man: the first one comes in the first line with

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear

which suggests that the person who is receiving this sonnet has beauties – for which in our language read beauty – to start with. This entirely applies to the Fair Youth.

The second lies in the gesture itself and the tone: handing a notebook to someone together with instructions on how to use it is something that one would do to a young person and we know for certain that the Fair Youth is a young man.

But this second match also casts our first and principal doubt: why is William Shakespeare, this far into what is clearly a pretty grown-up relationship with his young lover that has gone through admiration, desire, separation, betrayal, forgiveness, enjoined bliss, talking to him as if he were practically a child? It's not impossible: lovers do infantilise their darlings. The 20th century has taken this to some extreme that lingers today with people still calling each other 'babe' or 'baby'. But that's not quite the same thing. This sonnet in its entirety sounds like something a grown-up would write for a very young person, someone who is receiving their first book of commonplaces, not someone who is entirely familiar with the concept.

One of the chief candidates for the Fair Youth, Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton – and I emphasise here as I have done before that I will of course dedicate a special episode to the question of who the Fair Youth might be, because it may or may not be him – turns 21 on the 6th of October 1594. This might be an appropriate occasion for a poet to give his lover a notebook together with a sonnet, and he could be forgiven for making that sonnet sound like he's writing to a ten year old.

William Shakespeare's son Hamnet was baptised together with his twin sister Judith on the 2nd February 1585 and thus would have turned nine at the beginning of 1594. This would be approximately just the age at which in England you moved from Lower School to Middle School, and it is entirely possible – though it has to be said pure speculation on my part – that a poet and playwright father might want to gift his son a commonplace book with a paternally phrased piece of advice on how this will be useful for him in his life. Shakespeare would have no reason, at that time, to expect that he would lose his son just two years later, aged eleven.

Whoever the recipient is, what the poem does do in any case is assume that he will in one capacity or another be writing. This is not an unreasonable assumption to make for any educated boy or man of the era, and it goes hand in hand with the assumption that an educated boy or man of the era would have and make use of a book of commonplaces. It dates back to the classical tradition in Ancient Greece and Rome, rekindled in the Renaissance, where from an early age boys would maintain notebooks into which they would write commonplaces – tropes, sayings, quotes, snippets of dialogue, proverbs, poems – as well as their own thoughts and reflections, to build a treasury of arguments, turns of phrase, and other rhetorical devices that they could use in their own writing. That they would need writing skills, even if they were not setting out to become professional poets, was taken as read, since every man of note would have to be able to write correspondence, speeches, and quite likely love poems to help them woo their future betrothed or to charm their lovers. Girls and young women, by and large, in Shakespeare's day did not receive an education, with some notable exceptions, most prominent among them the Queen herself, who was schooled to a high level in private, and continued to learn all her life.

We are not now, nor are we ever likely to be, in a position to answer the questions this poem poses. It is worth asking them because as you will be aware if you've been following this podcast, some people question the validity of the assumption that the vast majority of these first 126 sonnets are written to one young man. In the last episode I made a strong case – or certainly, I strongly argued the case – for this being so. Here we meet the to my mind first genuinely plausible exception. Sonnet 77 could really have been written for someone else. It doesn't have to be, it fully lies within the scope that would be acceptable and applicable to the young man, but its content and the tone in which it conveys this content make it as fully compatible with the recipient being somebody else, someone who has nothing whatever to do with Shakespeare's lover, somebody most likely – if that were the case – quite a bit younger still.

There is also, of course, the possibility that Sonnet 77 was composed for the young lover, but much earlier in the relationship, before they even were lovers. Perhaps around the time of the Procreation Sonnets. Those are, as we saw and noted with interest, not poems that sound like they're addressed to a lover either, they too are teacherly and in the main driven by a purpose other than to communicate attraction, desire, or let alone lust, though even there we found a couple of exceptions when we looked at Sonnets 15 &16.

One further thought offers itself, and it is no less intriguing to entertain than the others: Sonnet 77 is the last sonnet before the entrance, with increasing fanfare, of the rival poet. Because starting with Sonnet 78, William Shakespeare becomes preoccupied, so as not to say obsessed with the presence in their relationship of another poet who, he believes – and we have good reason to believe for good reason – is usurping his place not only in the mind, but also in the heart, and quite possibly with the body too, of the young man.

And if it is the case, as we ventured it might be, that the young man is by now getting just a tad bored with the poetry his older lover is composing for him, then receiving a notebook with a doggerel that might best suit a child could just drive the nail into the coffin of passion. And that would place this poem right where we find it: bang at the key plot point of an unintended three act drama of not only passion but also power and possession...

Colin Burrow in the Oxford Edition of The Sonnets credits the 18th Century Shakespeare commentator George Steevens with first suggesting that this sonnet was written to accompany a notebook, and it is an attractive conclusion that makes sense, drawn from the line

And of this book this learning mayst thou taste

which clearly appears to refer to the book the reader holds in their hand at that moment. It is also possible, but seems signally less likely, that either, a) Shakespeare means 'that book', referring to the vacant leaves in a notebook the reader is expected to use generally, or b), that he in fact wrote 'that book', but the typesetter made a mistake or erroneously corrected him. But these two considerations, in view of the convincing probability of the Steevens theory, do appear purely academic, and I am noting them here mostly to signal that, as in almost everything concerning these sonnets, we are still talking about degrees of likelihood rather than absolute certainties.

Assuming then that this is so and that the sonnet does accompany a gift, the two most obvious questions to pursue are:

1: Who is this gift for? Is it our young man or could this be a sonnet that has slipped into the collection even though it is actually addressed to somebody completely different?

2: What's the occasion? What prompts Shakespeare to give this person such a book, together with a specially composed sonnet?

And the two are of course connected, with the latter perhaps being the more trivial one, since there are any number of reasons that offer themselves, contingent somewhat on how we are inclined to answer the first.

Two indicators point at a recipient that matches our young man: the first one comes in the first line with

Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear

which suggests that the person who is receiving this sonnet has beauties – for which in our language read beauty – to start with. This entirely applies to the Fair Youth.

The second lies in the gesture itself and the tone: handing a notebook to someone together with instructions on how to use it is something that one would do to a young person and we know for certain that the Fair Youth is a young man.

But this second match also casts our first and principal doubt: why is William Shakespeare, this far into what is clearly a pretty grown-up relationship with his young lover that has gone through admiration, desire, separation, betrayal, forgiveness, enjoined bliss, talking to him as if he were practically a child? It's not impossible: lovers do infantilise their darlings. The 20th century has taken this to some extreme that lingers today with people still calling each other 'babe' or 'baby'. But that's not quite the same thing. This sonnet in its entirety sounds like something a grown-up would write for a very young person, someone who is receiving their first book of commonplaces, not someone who is entirely familiar with the concept.

One of the chief candidates for the Fair Youth, Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton – and I emphasise here as I have done before that I will of course dedicate a special episode to the question of who the Fair Youth might be, because it may or may not be him – turns 21 on the 6th of October 1594. This might be an appropriate occasion for a poet to give his lover a notebook together with a sonnet, and he could be forgiven for making that sonnet sound like he's writing to a ten year old.

William Shakespeare's son Hamnet was baptised together with his twin sister Judith on the 2nd February 1585 and thus would have turned nine at the beginning of 1594. This would be approximately just the age at which in England you moved from Lower School to Middle School, and it is entirely possible – though it has to be said pure speculation on my part – that a poet and playwright father might want to gift his son a commonplace book with a paternally phrased piece of advice on how this will be useful for him in his life. Shakespeare would have no reason, at that time, to expect that he would lose his son just two years later, aged eleven.

Whoever the recipient is, what the poem does do in any case is assume that he will in one capacity or another be writing. This is not an unreasonable assumption to make for any educated boy or man of the era, and it goes hand in hand with the assumption that an educated boy or man of the era would have and make use of a book of commonplaces. It dates back to the classical tradition in Ancient Greece and Rome, rekindled in the Renaissance, where from an early age boys would maintain notebooks into which they would write commonplaces – tropes, sayings, quotes, snippets of dialogue, proverbs, poems – as well as their own thoughts and reflections, to build a treasury of arguments, turns of phrase, and other rhetorical devices that they could use in their own writing. That they would need writing skills, even if they were not setting out to become professional poets, was taken as read, since every man of note would have to be able to write correspondence, speeches, and quite likely love poems to help them woo their future betrothed or to charm their lovers. Girls and young women, by and large, in Shakespeare's day did not receive an education, with some notable exceptions, most prominent among them the Queen herself, who was schooled to a high level in private, and continued to learn all her life.

We are not now, nor are we ever likely to be, in a position to answer the questions this poem poses. It is worth asking them because as you will be aware if you've been following this podcast, some people question the validity of the assumption that the vast majority of these first 126 sonnets are written to one young man. In the last episode I made a strong case – or certainly, I strongly argued the case – for this being so. Here we meet the to my mind first genuinely plausible exception. Sonnet 77 could really have been written for someone else. It doesn't have to be, it fully lies within the scope that would be acceptable and applicable to the young man, but its content and the tone in which it conveys this content make it as fully compatible with the recipient being somebody else, someone who has nothing whatever to do with Shakespeare's lover, somebody most likely – if that were the case – quite a bit younger still.

There is also, of course, the possibility that Sonnet 77 was composed for the young lover, but much earlier in the relationship, before they even were lovers. Perhaps around the time of the Procreation Sonnets. Those are, as we saw and noted with interest, not poems that sound like they're addressed to a lover either, they too are teacherly and in the main driven by a purpose other than to communicate attraction, desire, or let alone lust, though even there we found a couple of exceptions when we looked at Sonnets 15 &16.

One further thought offers itself, and it is no less intriguing to entertain than the others: Sonnet 77 is the last sonnet before the entrance, with increasing fanfare, of the rival poet. Because starting with Sonnet 78, William Shakespeare becomes preoccupied, so as not to say obsessed with the presence in their relationship of another poet who, he believes – and we have good reason to believe for good reason – is usurping his place not only in the mind, but also in the heart, and quite possibly with the body too, of the young man.

And if it is the case, as we ventured it might be, that the young man is by now getting just a tad bored with the poetry his older lover is composing for him, then receiving a notebook with a doggerel that might best suit a child could just drive the nail into the coffin of passion. And that would place this poem right where we find it: bang at the key plot point of an unintended three act drama of not only passion but also power and possession...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!