Sonnet 40: Take All My Loves, My Love, Yea, Take Them All

|

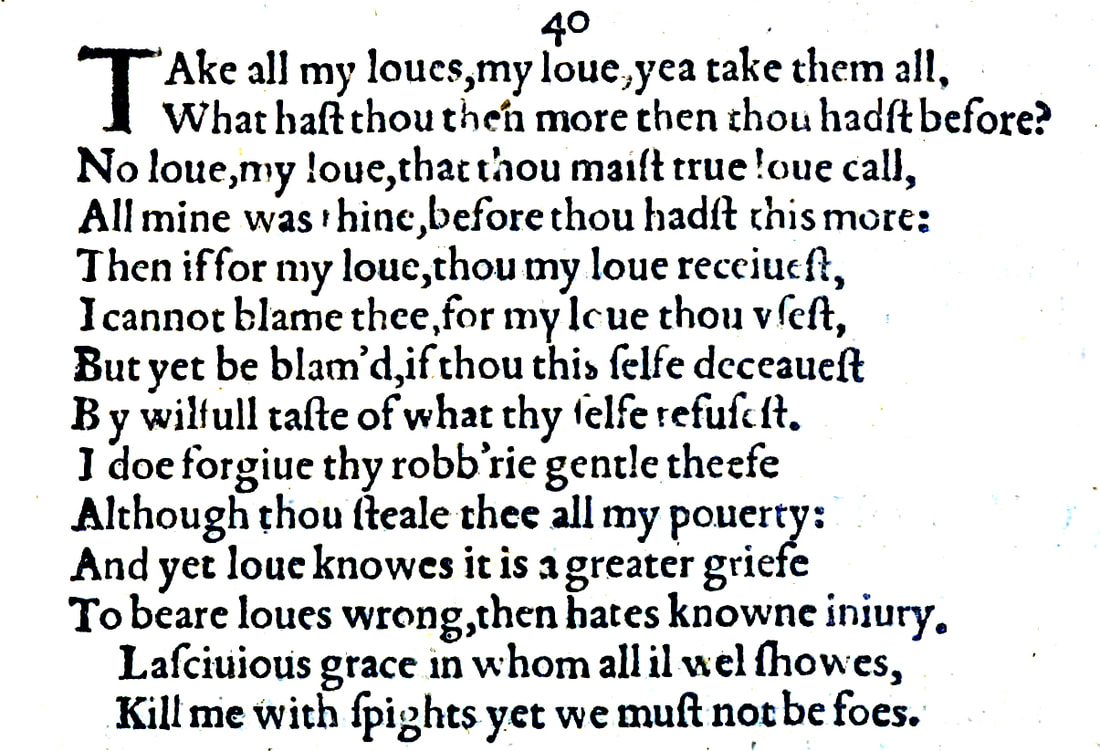

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all.

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before? No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call: All mine was thine before thou hadst this more. Then if for my love thou my love receivest, I cannot blame thee for my love thou usest; But yet be blamed if thou this self deceivest By wilful taste of what thyself refusest. I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief, Although thou steal thee all my poverty; And yet, love knows it is a greater grief To bear love's wrong than hate's known injury. Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows, Kill me with spites, yet we must not be foes. |

LISTEN TO SONNETCAST EPISODE 40

|

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all.

|

You, who are my love, take all the people I love, yes, take them all.

The sense implied is, of course, a sexual one, as well as one of appropriation: by 'having' this person who is my love, you, who are also my love, effectively take them away from me. |

|

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

|

When you have taken all the people I love, what more do you then have than you had before?

|

|

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call:

All mine was thine before thou hadst this more. |

Certainly not a love that you can call a true love:

everything that belongs to me was already yours, before you took this additional thing from me. And since I am your true love and everything that is mine is already yours, anything you take from me as if it were not already yours cannot be a true love. |

|

Then if for my love thou my love receivest,

|

There are three possible ways of reading this, which is probably absolutely intentional:

1 - Then if, out of love for me, you receive – as in take, and have, but it is a receiving because it really is already yours, since all that is mine is yours – this person whom I love... 2 – Then if, in the place of my love, as in: this person whom you take from me is a substitute for me... 3 – Then if, to make me love you even more, you do this, as in for the purpose of obtaining yet more of my love... |

|

I cannot blame thee for my love thou usest.

|

...then I can't blame you for using my love in this way. And here too, there is an obviously intentional double meaning: you use my love – my emotion by state of loving you – to justify your actions, but you also use, as in have sexual relations with, this other person whom I love.

|

|

But yet be blamed if thou this self deceivest

|

And yet, having said all that, you do have to take some blame if you deceive on the one hand this self that is me, on the other hand this self that is made up of the two of us, and therefore by deduction this self that is also you.

Many editors emend the Quarto Edition's 'this self' to the more obvious 'thyself', which makes perfect sense, but seems unnecessary and also takes away this multiple layering that Shakespeare may very well have intended. |

|

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

|

...by wilfully tasting – as in sampling, consuming, even experimenting with – that which you yourself actually normally refuse.

The sexual-sensual current continues, and is reinforced with the word 'wilful' which in itself carries a strong connotation of deliberate lustfulness, and may also on top of that be yet another fully intended pun on both Will's name and the male sexual organ. The 'refusest', meanwhile is often read as mostly meaning to suggest that the young man scorns at people who have these kinds of sexual affairs, but given the young man's history of refusing women whom he is meant to marry, it seems signally more obvious and more likely that Shakespeare is referring directly to the young man's refusal of women quite generally so far, except now, with this love of his, Shakespeare's, whom the young man clearly has had a wilful 'taste' of. |

|

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty; |

I forgive you your robbery, gentle thief, even if you steal everything from me, which, being but a poor poet, is not much, and certainly, by implication, way less than you have.

|

|

And yet, love knows, it is a greater grief

To bear love's wrong than hate's known injury. |

And yet, love knows – which is similar to God knows, but gives us one more opportunity to use the word 'love', which is clearly central to this entire poem – it is worse and causes more upset and grief having to bear the wrongs committed by a lover or someone whom you love than to suffer the familiar and therefore known injuries caused by someone of whom you know that they hate you.

|

|

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

|

You, who are both lustful, and wanton, and in the juice of your youth, and who are graceful and young, but also, on account of your nobility, entitled to be addressed as Grace; you, in whom everything looks good, even the bad things you do – 'all ill' is everything that is untoward, not right, awry or amiss, and even all of that shows well in you, meaning that you make it look good – ...

'Lascivious', as John Kerrigan points out, is less judgmental and damning than we might usually interpret here today. |

|

Kill me with spites, yet we must not be foes.

|

Kill me with your misdeeds, your vexations, your malicious actions, but we must not be enemies.

|

With his forcefully forgiving Sonnet 40, William Shakespeare finally connects us right back to Sonnet 35 and sets out on a short sequence which explains with startling frankness what has happened and what should now, and, more to the point, should not now be the consequence of this. That Shakespeare feels desolate about his lover's 'ill deeds' is beyond doubt, as is the fact that this sonnet goes straight to the heart of the matter: love. This poet, who has the greatest vocabulary of any writer in the English language if not ever then certainly up until then uses the word 'love' ten times here – more often than in any other sonnet – to mean either the emotion itself or whoever may be this other person or indeed these other people whom he directs this emotion towards in a relationship that has suddenly become at the very least triangular in the most spectacular fashion.

When Sonnet 35 left us in little doubt about the nature of the young man's transgression without actually spelling it out, Sonnet 40 seals the lid on this and makes it as clear as can be that what this 'sweet thief' has stolen from William Shakespeare is – much as we surmised – not an orange, but a love. Who this love is we don't know, but as we noted then, it is obviously not Anne, Shakespeare's wife. It is another love.

This makes Sonnet 40 fascinating beyond anything we had until recently been led to expect. Right up until Sonnet 35 we got the impression that William Shakespeare is uniquely and – apart from Anne, his wife in Stratford – exclusively devoted to his young man. So much adoration, adulation, admiration had been directed towards him that we could be forgiven for thinking that – besides Anne perhaps, with their children – he, the young man, was the only person in Shakespeare's life who really matters.

Apparently not so. This sonnet sets somebody else on a par with the young man. It is, I believe, the only one to do so and soon Shakespeare will draw a very clear distinction between the young man and this other person, but going by this sonnet and the words this sonnet contains alone, we have here a poet outraged not about his lover having gone astray elsewhere randomly – as seemed to be the case with Sonnets 33 and 34 – but very much, and as Sonnet 35 appeared to suggest, with another love of his. And here it may be practical to anticipate a bit, because the temptation would be to call this other love another lover, but in our use of the English language that would strongly suggest another man, and while Sonnet 40 doesn't tell us what gender this other person identifies as, Sonnets 41 and 42 will give it to us in writing that we are talking here about a woman.

Our understanding of Shakespeare is newly stood on its head. Up until recently we had him married to Anne Hathaway in Stratford, while in London clearly, wholly, consumed with love and passion for this one young man. Repeating myself somewhat just to drive home this point: nothing in the sequence so far has suggested either that a) any of these sonnets until now – including the first 17 'Procreation Sonnets' – were directed at anyone other than the same young man, or, b) that there is anyone else receiving Shakespeare's affections to any level that might be considered noteworthy. What Sonnet 40 spells out in more or less the Shakespearean equivalent to a bright LED sign in capital letters is that: I HAVE ANOTHER LOVE AND YOU HAVE TAKEN HER FROM ME. And here the use of words, if it hadn't been so before, becomes super-significant:

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all.

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

Other people: 1

Young man: 1

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call:

All mine was thine before thou hadst this more.

Love itself: 2

Young man: 1

Then if for my love thou my love receivest

I cannot blame the for my love thou usest;

Love itself: 1

Other person: 2

And yet, love knows, it is a greater grief

To bear love's wrong than hate's known injury.

Love itself: 2

I do not mean to suggest that William Shakespeare himself sat down and counted the instances in which he uses the word 'love' and made sure he allocated them in a specific way, but what we learn from looking back and counting is that this sonnet on its own gives an equivalence to this other person: she – as it will soon turn out to be – is called 'love' twice, he is addressed as 'love' twice, love itself is named and invoked, almost conjured, one might feel, five times, and these generic other loves who may or may not exist but who are always a potential in any case are mentioned only once but first.

There have been occasions when we were given the impression that the young man responded to a sonnet he received from William Shakespeare by directly or indirectly putting the poet in his place. This sonnet, either consciously or – perhaps more likely subconsciously – does something similar in reverse: Shakespeare, clearly upset, clearly dejected, lets the young man know in no uncertain terms that he is not the only one.

And yet he is. This is a sonnet, after all, and one of 126 that we know of to be more or less directly addressed to or about or composed in the context of the young man and Shakespeare cannot bring himself to be angry forever:

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty.

Even though it pains me more - as it does anyone – to be thus injured by someone you love than by someone you know already hates you, I build up to the closing couplet which, resigned and defiant, depleted and resilient all at the same time, returns you the young man to your special, your unchallenged place in my heart:

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites, yet we must not be foes.

There is a way out of this and I am beginning to pave it right now.

It's an astonishing sonnet, this, and it contains one more nugget that absolutely is worth picking out and polishing just for one more closer inspection:

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

Because indeed: what on earth prompted the young man to get off with his lover's 'love'? Who does such a thing? And why? Everything we know so far, including this particular line, points towards a young man – beyond measure wealthy, connected, powerful, young, beautiful, attractive, uninterested in women – who could have anyone. Why go for the mistress of the man who professes his undying love for you? Out of spite? Jealousy? To test this love? To 'pull rank', effectively, and say: remember, I'm the one here who counts, so if you go off elsewhere, then I'll come with you? Almost too literally?

And who – still this question, ever looming larger now, of course – just who is this other love? We don't know. Yet. There will be a whole different sequence much later in the collection, which appears to mirror these events. This has led many readers, scholars, and editors, including me, to believe that the 'Dark Lady' of those 'later' sonnets – later in the collection but in that case simultaneous in time – is exactly this here 'love'. But we don't know. We will never know entirely for certain, but we will get more and more illustrative pieces of this ever growing jigsaw, and in the short term, we are just about to get confirmation that yes, this other person, this other love that you have taken from me is a woman, but no, whatever this here sonnet may be suggesting, she is – in both applicable senses of the word – no match for you.

When Sonnet 35 left us in little doubt about the nature of the young man's transgression without actually spelling it out, Sonnet 40 seals the lid on this and makes it as clear as can be that what this 'sweet thief' has stolen from William Shakespeare is – much as we surmised – not an orange, but a love. Who this love is we don't know, but as we noted then, it is obviously not Anne, Shakespeare's wife. It is another love.

This makes Sonnet 40 fascinating beyond anything we had until recently been led to expect. Right up until Sonnet 35 we got the impression that William Shakespeare is uniquely and – apart from Anne, his wife in Stratford – exclusively devoted to his young man. So much adoration, adulation, admiration had been directed towards him that we could be forgiven for thinking that – besides Anne perhaps, with their children – he, the young man, was the only person in Shakespeare's life who really matters.

Apparently not so. This sonnet sets somebody else on a par with the young man. It is, I believe, the only one to do so and soon Shakespeare will draw a very clear distinction between the young man and this other person, but going by this sonnet and the words this sonnet contains alone, we have here a poet outraged not about his lover having gone astray elsewhere randomly – as seemed to be the case with Sonnets 33 and 34 – but very much, and as Sonnet 35 appeared to suggest, with another love of his. And here it may be practical to anticipate a bit, because the temptation would be to call this other love another lover, but in our use of the English language that would strongly suggest another man, and while Sonnet 40 doesn't tell us what gender this other person identifies as, Sonnets 41 and 42 will give it to us in writing that we are talking here about a woman.

Our understanding of Shakespeare is newly stood on its head. Up until recently we had him married to Anne Hathaway in Stratford, while in London clearly, wholly, consumed with love and passion for this one young man. Repeating myself somewhat just to drive home this point: nothing in the sequence so far has suggested either that a) any of these sonnets until now – including the first 17 'Procreation Sonnets' – were directed at anyone other than the same young man, or, b) that there is anyone else receiving Shakespeare's affections to any level that might be considered noteworthy. What Sonnet 40 spells out in more or less the Shakespearean equivalent to a bright LED sign in capital letters is that: I HAVE ANOTHER LOVE AND YOU HAVE TAKEN HER FROM ME. And here the use of words, if it hadn't been so before, becomes super-significant:

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all.

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

Other people: 1

Young man: 1

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call:

All mine was thine before thou hadst this more.

Love itself: 2

Young man: 1

Then if for my love thou my love receivest

I cannot blame the for my love thou usest;

Love itself: 1

Other person: 2

And yet, love knows, it is a greater grief

To bear love's wrong than hate's known injury.

Love itself: 2

I do not mean to suggest that William Shakespeare himself sat down and counted the instances in which he uses the word 'love' and made sure he allocated them in a specific way, but what we learn from looking back and counting is that this sonnet on its own gives an equivalence to this other person: she – as it will soon turn out to be – is called 'love' twice, he is addressed as 'love' twice, love itself is named and invoked, almost conjured, one might feel, five times, and these generic other loves who may or may not exist but who are always a potential in any case are mentioned only once but first.

There have been occasions when we were given the impression that the young man responded to a sonnet he received from William Shakespeare by directly or indirectly putting the poet in his place. This sonnet, either consciously or – perhaps more likely subconsciously – does something similar in reverse: Shakespeare, clearly upset, clearly dejected, lets the young man know in no uncertain terms that he is not the only one.

And yet he is. This is a sonnet, after all, and one of 126 that we know of to be more or less directly addressed to or about or composed in the context of the young man and Shakespeare cannot bring himself to be angry forever:

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty.

Even though it pains me more - as it does anyone – to be thus injured by someone you love than by someone you know already hates you, I build up to the closing couplet which, resigned and defiant, depleted and resilient all at the same time, returns you the young man to your special, your unchallenged place in my heart:

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites, yet we must not be foes.

There is a way out of this and I am beginning to pave it right now.

It's an astonishing sonnet, this, and it contains one more nugget that absolutely is worth picking out and polishing just for one more closer inspection:

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

Because indeed: what on earth prompted the young man to get off with his lover's 'love'? Who does such a thing? And why? Everything we know so far, including this particular line, points towards a young man – beyond measure wealthy, connected, powerful, young, beautiful, attractive, uninterested in women – who could have anyone. Why go for the mistress of the man who professes his undying love for you? Out of spite? Jealousy? To test this love? To 'pull rank', effectively, and say: remember, I'm the one here who counts, so if you go off elsewhere, then I'll come with you? Almost too literally?

And who – still this question, ever looming larger now, of course – just who is this other love? We don't know. Yet. There will be a whole different sequence much later in the collection, which appears to mirror these events. This has led many readers, scholars, and editors, including me, to believe that the 'Dark Lady' of those 'later' sonnets – later in the collection but in that case simultaneous in time – is exactly this here 'love'. But we don't know. We will never know entirely for certain, but we will get more and more illustrative pieces of this ever growing jigsaw, and in the short term, we are just about to get confirmation that yes, this other person, this other love that you have taken from me is a woman, but no, whatever this here sonnet may be suggesting, she is – in both applicable senses of the word – no match for you.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!