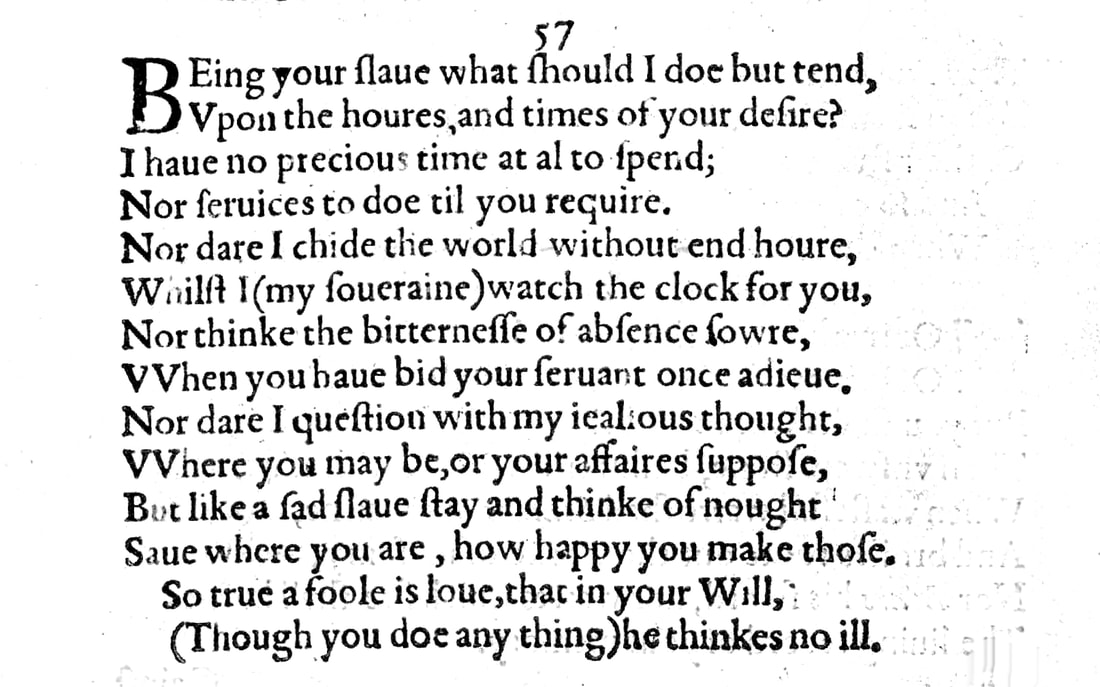

Sonnet 57: Being Your Slave, What Should I Do But Tend

|

Being your slave, what should I do but tend

Upon the hours and times of your desire? I have no precious time at all to spend, Nor services to do, till you require. Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you, Nor think the bitterness of absence sour When you have bid your servant once adieu. Nor dare I question with my jealous thought Where you may be, or your affairs suppose, But like a sad slave stay and think of nought, Save where you are, how happy you make those. So true a fool is love that in your will, Though you do anything, he thinks no ill. |

|

Being your slave, what should I do but tend

Upon the hours and times of your desire? |

Seeing that I am your slave, what should I do other than to wait for you and attend you and respond to your every whim and desire, much as a servant or slave would do in relation to their master?

The question is of course a rhetorical one, which invites the answer 'nothing', but an important nuance lies in the phrasing. Shakespeare does not ask, 'what should I do but attend you?' directly, but 'what should I do but attend the hours and times of your desire?' which makes it clear that what prompts the sonnet is not so much a feeling Shakespeare has that he is being put in a position where he is acting as his young lover's servant and having to run errands for him, but that he is having to wait around for him, in the process, as the following lines are about to suggest, wasting his own time and neglecting his own other concerns, such as they are. And an additional layer of meaning may possibly be found in these "hours and times of your desire," because both this sonnet and the one that follows it, Sonnet 58, with which it clearly forms a pair, suggest that the young man is out and about conducting not only business but also other relationships and sexual encounters, and if that is the case, then the implication here is that Shakespeare is having to wait around for him, while the young man is going around following his desires, including sexual ones, elsewhere. |

|

I have no precious time at all to spend,

Nor services to do, till you require. |

I have no precious time of mine own that I would wish to spend on myself, doing other things, nor do I have any obligations or duties or even chores that I have to do, until you need me or need me to do something for you.

Patently this is not the reality of Shakespeare's life: we know that he had a very busy existence, writing not only these sonnets, but also many plays in very short succession, and he was working as an actor and an entrepreneurial member and co-owner of a theatre company, and he had a family in Stratford who depended upon him financially, so clearly he is being somewhat facetious. Whether or not Shakespeare here is being truly and deliberately sarcastic will merit further investigation when we look at the poem and its companion piece, Sonnet 58, in the round, because the tone he strikes here that invites such a conclusion certainly continues: |

|

Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour

Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you, |

Nor would I dare to reproach or criticise the endless hours during which I wait and watch the clock for you, you being as a ruler or king to me.

Employing the term 'sovereign' here, which would really usually be applied to the king or queen, highlights the exaggerated discrepancy that Shakespeare demarcates between himself as a 'slave' and his young lover. There may or may not be an allusion to 'queen' and to 'quean', the former being the sovereign of England at the time, the latter meaning "an impudent or badly behaved girl or woman" or simply "a prostitute" (Oxford Dictionaries), and if these two sonnets were to serve to admonish the young man for his licentious behaviour, then calling him in one go your king (as in absolute ruler or master), your queen (as in the equivalent to the most powerful person in the country), and a whore would make for pretty nifty wordsmithery on the part of William Shakespeare. 'World-without-end', meanwhile, is a particularly evocative way of saying 'endless', and Shakespeare uses it only once elsewhere, in Love's Labours Lost, where he has the Princess refer to a 'world-without-end' bargain. |

|

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour

When you have bid your servant once adieu. |

Nor dare I consider the bitter taste that your absence invariably leaves me with to be all that sour, once you have bid me, who I am your servant, 'adieu'.

The line can also be read simply as: 'nor do I consider or think the bitterness of absence sour', as opposed to 'nor dare I', but since 'dare' is repeated in the next quatrain, I'm inclined to interpret the 'dare' above to apply throughout this quatrain too. 'Adieu', quite apart from enabling the required rhyme with 'you', is also telling: it is the form of 'goodbye' used in English to mark a departure for a long time, even forever, and this placing here is obviously designed to emphasise the long periods over which the young man absents himself from Shakespeare. |

|

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought

Where you may be, or your affairs suppose, |

Nor do I dare jealously question where you may be or hazard a guess as to what you are up to.

'Affairs' here does not on its own necessarily imply a sexual or romantic liaison: the word was used simply to mean 'business' or 'dealings', though in the context here these dealings may well be implied to be of a sexual nature. |

|

But like a sad slave stay and think of nought,

Save where you are, how happy you make those. |

But like a sad slave I am to stay at home or wherever else I am and think of nothing, except how happy you make the people around you who enjoy the privilege of your company, wherever you happen to be.

'Stay' here too comes with multiple meanings that combine to convey a powerful image: it may mean 'stay at home' or 'stay in the place that I'm confined to', as distinct from the place where you are. It also means 'remain in attendance and in service', in other words, I am at your beck and call, and it is what you tell a dog when you don't want it to follow you or move around. |

|

So true a fool is love that in your will,

Though you do anything, he thinks no ill. |

So trusting, faithful, and sincere a fool is love that although you may do anything you want, he, love, thinks no ill of you.

This concluding couplet conflates love itself with the lover and effectively refers to William Shakespeare not only in the third person singular as the young man's lover, but as 'love', which, applied to a person, has a subtly diminutive effect, as in the very colloquial 'alright, love?', or, even where that is not the case or the intention, renders the person in love passive and recipient of – possibly wishful for – love as opposed to the agent of his own love and desire, the way the word 'lover' does. Shakespeare makes it clear that he is talking about himself, not least by slipping in a double double entendre with 'will'. One is a pun on his own name – a device he uses much later in the collection almost to the point of overbearing excess – and one on sexual activity and desire and the sexual organ. This multiple layering once again is no doubt deliberate as it allows Shakespeare to make quite forthright allegations against his young man while superficially claiming not to be bothered by his conduct at all and seeming to subject himself to the young man's social superiority and to his whims and fancies. And although spellings and capitalisations in the Quarto Edition are far from consistent and therefore not dependable as indicators of intended additional meanings or puns, it may be significant and is certainly noteworthy that here the word 'Will' is capitalised. |

Sonnets 57 & 58 once again come as a strongly linked pair, and with these sonnets , William Shakespeare positions himself at such a pointedly subservient angle to his lover that we may be forgiven for detecting in them a really rather rare and therefore all the more startling note of sarcasm. The argument that is being pursued is simple enough: I am your slave and therefore you are at liberty to do whatever you want, wherever you choose, with whomsoever you desire, and far be it from me to try to have any say or let alone control over how you spend your time.

As on previous occasions, we shall look at the two poems together in the next episode, while concentrating on the first one of the two for now.

The idea that William Shakespeare's lover is a person of considerable social status has long formed itself in our mind. From the beginning of the Procreation Sequence, which consists of Sonnets 1-17, right into the bulk of what are commonly referred to as the Fair Youth Sonnets, which are all the sonnets, including the Procreation Sequence, from Sonnet 1 until now, and usually considered to continue and encompass the majority of the sonnets up to and including Sonnet 126, we noted that the young man addressed or talked about by certainly the sonnets so far seems to be the same person.

I need to stress, as I have done before: there is no external proof of this, and you will hear people argue in a different direction, namely that these sonnets may be addressed to a whole wide range of people, both men and women. And technically that may be so. But listening carefully and in great detail, as we have been doing, to what the words of these sonnets tell us, we keep finding character traits, events, behaviours and what appear to be Shakespeare's responses to these behaviours that feed a particular profile, which is of a person who meets certain criteria. We have looked at them and listed them before and I will of course dedicate a special episode to this young man and examine the various possibilities that exist for his identity or indeed identities to a much greater depth, but these two Sonnets, 57 & 58, make such a singularly special point about Shakespeare's station in life in relation to his young lover, that it is well worth attempting a short recap of references to status thus far.

Of the entire Procreation Sequence, Sonnets 1-17, we were fairly sure that it must be addressed to a young man who is in the eyes of the world – the world here meaning London society or English society – and who is seen to be of some importance by society, for reasons we explored there but which, in a nutshell, amount to an observation that in order for a young man to be so urged by a poet – very possibly on a commission – to produce an heir, there must be something at stake: a name, an estate, a family line, a reputation, a future. The young man is presented in these poems as someone who is known, admired, even revered, rather than as an ordinary subject of the Queen, and certainly not as William Shakespeare’s peer, such as a fellow actor or poet, or a member of his own family.

In Sonnet 20, Shakespeare acknowledges the fact that the young man he is smitten with has the appearance of a woman and addresses him as "master-mistress of my passion." This on its own does not mean that the recipient has to be a nobleman, but it means here is a first instance where Shakespeare uses terminology that suggests an either real or perceived imbalance between him and his lover, whom indeed by now he views and characterises as a lover.

In Sonnet 26, Shakespeare opens with the line “Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage | Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit,” and goes on to declare that this duty is so great that a “wit so poor as mine | May make seem bare in wanting words to show it,” and that therefore he, Shakespeare, will not be able to present himself to his lover or boast of his love for him until fortune has turned him into a better poet.

Irrespective of whether this has happened or not, Sonnet 32 put forward the prospect that Shakespeare’s poetry would be “exceeded by the height of happier men,” and requested of the young man that he keep these verses for the sake of their love, even though he would be bound to receive better ones from virtually everyone else, which presupposes that the young man is in a position where poets of every ilk would compose poetry for him. This, again, is not something that happens to the stable boy or the footman – valuable humans though they be – or the youth who plays the girls in the theatre, the latter at least not on a grand scale. Although it may be true that he too, much as the footman and indeed the stable boy may all have their own admirers too...

Sonnet 33, although complaining bitterly about the young man’s conduct still refers to him as one of several “suns of the earth,” which immediately confers on him an elevated status too, and Sonnet 37, by now again in a conciliatory mood, speaks of the “beauty, birth or wealth or wit,” that the young man is endowed with of which beauty and wit may well be gifts that anyone, including the stable boy, the footman, or the boy playing the girls in a troupe of actors, can possess, but birth and wealth really sit exclusively with the privileged few, who are generally speaking, in Elizabethan England, the aristocracy.

Sonnet 38 again suggests that there may be many other poets similarly enticed to write poetry for the young man, and then Sonnet 40, although it once more, and quite forcefully, admonishes him, calls the young man “lascivious grace,” and that would be entirely uncalled for, were it not for the young man in all likelihood being a titled member of the nobility to whom the address ‘Grace’ would actually and appropriately apply.

There have been two or three subtler instances where we were either reminded or given to understand that Shakespeare views his young man as someone who is of an elevated status in society, and if you have been listening to this podcast, you may remember my conversation with Professor Stephen Regan who also noted how much many of these sonnets reflect on this particular theme.

Nowhere until now though has Shakespeare quite so let rip on the motif of status, and nowhere until now has he expressed himself so strongly in terms that make us wonder just how sincere he is being. He has been mildly sarcastic, or certainly, we thought, ironic before, not least when he disparaged his own writing, but to our ears today Sonnet 57 comes across as more than just borderline peeved: it comes close to being poetically passive-aggressive.

This, we have to bear in mind though, may be merely our perception, and the closing couplet of this sonnet does appear to show a degree of self-awareness and insight that softens the tenor of the rest of the sonnet into an almost laconic shrug of the shoulders that admits: well, I am a fool for being so beholden to you and making me so your slave, but that is how genuine and faithful I am in my love for you.

And so even though we may find it hard to take Will entirely seriously with this sonnet, he does not actually leave us suspended in a great deal of doubt, but rather in a place where we have to concede: maybe he isn’t being facetious at all, maybe he really does feel like that about his young man and is in essence content to be thus in his thrall, he, this young man, is a splendid specimen, after all.

Sonnet 58 will disabuse us of most of this notion, as Shakespeare cranks it all up several notches and concludes his ‘argument’, such as it is, though resigned to the situation, most certainly not in what we can call a happy disposition.

As on previous occasions, we shall look at the two poems together in the next episode, while concentrating on the first one of the two for now.

The idea that William Shakespeare's lover is a person of considerable social status has long formed itself in our mind. From the beginning of the Procreation Sequence, which consists of Sonnets 1-17, right into the bulk of what are commonly referred to as the Fair Youth Sonnets, which are all the sonnets, including the Procreation Sequence, from Sonnet 1 until now, and usually considered to continue and encompass the majority of the sonnets up to and including Sonnet 126, we noted that the young man addressed or talked about by certainly the sonnets so far seems to be the same person.

I need to stress, as I have done before: there is no external proof of this, and you will hear people argue in a different direction, namely that these sonnets may be addressed to a whole wide range of people, both men and women. And technically that may be so. But listening carefully and in great detail, as we have been doing, to what the words of these sonnets tell us, we keep finding character traits, events, behaviours and what appear to be Shakespeare's responses to these behaviours that feed a particular profile, which is of a person who meets certain criteria. We have looked at them and listed them before and I will of course dedicate a special episode to this young man and examine the various possibilities that exist for his identity or indeed identities to a much greater depth, but these two Sonnets, 57 & 58, make such a singularly special point about Shakespeare's station in life in relation to his young lover, that it is well worth attempting a short recap of references to status thus far.

Of the entire Procreation Sequence, Sonnets 1-17, we were fairly sure that it must be addressed to a young man who is in the eyes of the world – the world here meaning London society or English society – and who is seen to be of some importance by society, for reasons we explored there but which, in a nutshell, amount to an observation that in order for a young man to be so urged by a poet – very possibly on a commission – to produce an heir, there must be something at stake: a name, an estate, a family line, a reputation, a future. The young man is presented in these poems as someone who is known, admired, even revered, rather than as an ordinary subject of the Queen, and certainly not as William Shakespeare’s peer, such as a fellow actor or poet, or a member of his own family.

In Sonnet 20, Shakespeare acknowledges the fact that the young man he is smitten with has the appearance of a woman and addresses him as "master-mistress of my passion." This on its own does not mean that the recipient has to be a nobleman, but it means here is a first instance where Shakespeare uses terminology that suggests an either real or perceived imbalance between him and his lover, whom indeed by now he views and characterises as a lover.

In Sonnet 26, Shakespeare opens with the line “Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage | Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit,” and goes on to declare that this duty is so great that a “wit so poor as mine | May make seem bare in wanting words to show it,” and that therefore he, Shakespeare, will not be able to present himself to his lover or boast of his love for him until fortune has turned him into a better poet.

Irrespective of whether this has happened or not, Sonnet 32 put forward the prospect that Shakespeare’s poetry would be “exceeded by the height of happier men,” and requested of the young man that he keep these verses for the sake of their love, even though he would be bound to receive better ones from virtually everyone else, which presupposes that the young man is in a position where poets of every ilk would compose poetry for him. This, again, is not something that happens to the stable boy or the footman – valuable humans though they be – or the youth who plays the girls in the theatre, the latter at least not on a grand scale. Although it may be true that he too, much as the footman and indeed the stable boy may all have their own admirers too...

Sonnet 33, although complaining bitterly about the young man’s conduct still refers to him as one of several “suns of the earth,” which immediately confers on him an elevated status too, and Sonnet 37, by now again in a conciliatory mood, speaks of the “beauty, birth or wealth or wit,” that the young man is endowed with of which beauty and wit may well be gifts that anyone, including the stable boy, the footman, or the boy playing the girls in a troupe of actors, can possess, but birth and wealth really sit exclusively with the privileged few, who are generally speaking, in Elizabethan England, the aristocracy.

Sonnet 38 again suggests that there may be many other poets similarly enticed to write poetry for the young man, and then Sonnet 40, although it once more, and quite forcefully, admonishes him, calls the young man “lascivious grace,” and that would be entirely uncalled for, were it not for the young man in all likelihood being a titled member of the nobility to whom the address ‘Grace’ would actually and appropriately apply.

There have been two or three subtler instances where we were either reminded or given to understand that Shakespeare views his young man as someone who is of an elevated status in society, and if you have been listening to this podcast, you may remember my conversation with Professor Stephen Regan who also noted how much many of these sonnets reflect on this particular theme.

Nowhere until now though has Shakespeare quite so let rip on the motif of status, and nowhere until now has he expressed himself so strongly in terms that make us wonder just how sincere he is being. He has been mildly sarcastic, or certainly, we thought, ironic before, not least when he disparaged his own writing, but to our ears today Sonnet 57 comes across as more than just borderline peeved: it comes close to being poetically passive-aggressive.

This, we have to bear in mind though, may be merely our perception, and the closing couplet of this sonnet does appear to show a degree of self-awareness and insight that softens the tenor of the rest of the sonnet into an almost laconic shrug of the shoulders that admits: well, I am a fool for being so beholden to you and making me so your slave, but that is how genuine and faithful I am in my love for you.

And so even though we may find it hard to take Will entirely seriously with this sonnet, he does not actually leave us suspended in a great deal of doubt, but rather in a place where we have to concede: maybe he isn’t being facetious at all, maybe he really does feel like that about his young man and is in essence content to be thus in his thrall, he, this young man, is a splendid specimen, after all.

Sonnet 58 will disabuse us of most of this notion, as Shakespeare cranks it all up several notches and concludes his ‘argument’, such as it is, though resigned to the situation, most certainly not in what we can call a happy disposition.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!