Sonnet 21: So Is it Not With Me as With That Muse

|

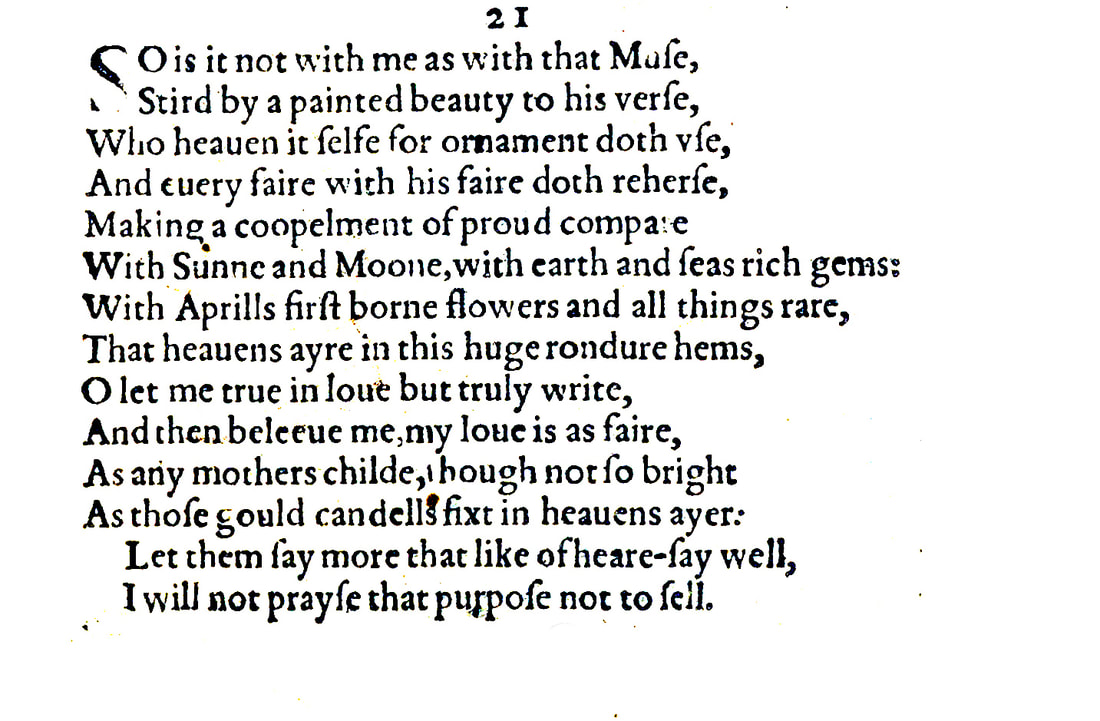

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse, Who heaven itself for ornament doth use, And every fair with his fair doth rehearse, Making a couplement of proud compare With sun and moon, with earth and sea's rich gems, With April's first-born flowers and all things rare That heaven's air in this huge rondure hems. O let me, true in love, but truly write, And then, believe me, my love is as fair As any mother's child, though not so bright As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air. Let them say more that like of hearsay well, I will not praise that purpose not to sell. |

|

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse, |

I am not like that other kind of poet who, stirred or inspired to write his verses by a 'painted beauty', meaning a woman who tries to make herself look beautiful by wearing heavy makeup...

|

|

Who heaven itself for ornament doth use,

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse, |

...the kind of poet who uses heaven itself as an ornament to describe this 'beauty' of his affection and goes on and on about her, employing everything he can find in the world that is beautiful to exalt her...

Note that 'heaven' here is pronounced with one syllable in order for the line to scan. |

|

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea's rich gems, |

...proudly – and thus by implication immodestly or boastfully – comparing her with the sun, the moon, and the 'rich gems' – the wealth of beautiful things – he finds or can think of on earth or in the sea...

|

|

With April's first-born flowers and all things rare

That heaven's air in this huge rondure hems. |

...with the first flowers that bloom in spring and absolutely everything that is rare and therefore precious under the sun. 'Heaven's air' is the sky and 'this huge rondure' is our world which is enclosed, or 'hemmed' by the sky.

|

|

O let me, true in love, but truly write,

|

By contrast to that kind of poet who does these things and effectively makes wild exaggerations in the praise of his 'painted' beauty', let me only write the truth...

|

|

And then, believe me, my love is a fair

As any mother's child, though not so bright As those gold candles fixed in heaven's air. |

...and then, when I do so, believe me, you will find that my love is as beautiful as any mother's child, meaning as anyone is or can be, though obviously he is not and cannot be as bright as the stars – those gold candles – which are fixed in the sky.

|

|

Let them say more that like of hearsay well

I will not praise that purpose not to sell. |

Let those who enjoy gossip and hyperbole and idle chitchat say more than that and go on and on in the most extravagant terms about how beautiful the person of their affection is. I, who want to speak the truth and nothing else, will not praise to the hilt something or someone that is not for sale. In other words: I am not going to cheapen my love by overpraising him like some goods that a market stall holder might try to flog off by making ridiculous claims about them.

|

The distinctive and sincere Sonnet 21 stands out as the first in the series in which William Shakespeare addresses an unspecified general 'audience' to talk about his love – as opposed to the young man directly, or a personified concept, such as Time – and it is also the first one to reference the poetry of somebody else or of other people. It therefore marks an especially significant stage in the development of the relationship and a notable new stance with which Shakespeare positions himself towards his love and the outside world.

Some editors have speculated that Shakespeare with 'that muse' may be referring to the 'rival poet' who makes his appearance later in the series when he seems to usurp Shakespeare's place as his young lover's favourite poet. As with so many other things concerning these poems, we cannot say with any certainty whether or not this is the case, but what mostly speaks against this idea is that the sonnets in which the 'rival poet' features are generally accepted as Sonnets 78 to 86 and that there is no concrete indication that Shakespeare here has a specific individual in mind. By some margin more likely therefore is that 'that muse' is simply a generic sideswipe at the kind of poet who indulges in the practices that Shakespeare so scornfully lists. Colin Burrow, Editor of the Oxford World's Classics edition of the Sonnets points out that by the time Shakespeare writes these sonnets, he is not the only one to criticise overly flowery language in poetry, and particularly highlights a book known as both Apology for Poetry and The Defence of Poetry by Shakespeare's contemporary Sir Philip Sidney as a primary example.

It is certainly interesting to note that Shakespeare delineates himself against what he emphatically considers bad poetry, and once again against fakery. And in this context the reference, directly following on from Sonnet 20, to a 'painted beauty' is telling.

We noted there and at least once earlier that Shakespeare does not hold women who wear heavy makeup in too high regard, and it may be worth observing at this juncture that the kind of makeup some women wore in the Elizabethan age – including the Queen herself – was not always exactly a subtle affair: often thick layers of quite literally 'face paint' were applied to cover up blemishes, the ravages of disease, and the signs of old age. Women who worked as courtesans – what today we would call sex workers – in an age before antibiotics and effective healthcare were particularly susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases, symptoms of which were facial blisters and lesions, among many others, and often these were simply covered up with makeup. So Shakespeare's disdain for 'painted beauty' compared to natural beauty may not be purely down to aesthetics. And he does close by stressing how his love – the young man – does not purpose to sell himself. In matters of 'love' and 'beauty', those whom we most commonly tend to associate with 'selling' are, indeed, sex workers.

What is perhaps most striking for us though is the sincerity of tone that comes with the third quatrain:

O let me, true in love, but truly write

And then believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother's child

This takes us onto a new and different level from where we were only a few sonnets ago. After the flourish of Sonnet 18 we had Shakespeare speak to Time itself, saying: "I forbid thee one most heinous crime," namely to carve "my love's fair brow,"

and we took note there how that was the first time we could not be in any doubt that Shakespeare was referring to the young man who receives these sonnets as his 'love'; in Sonnet 20 then he elaborates frankly and a little saucily on the fact that this love is in fact a man and calls him the "master-mistress of my passion."

Both of these are telling and we also felt we were given to believe by these two sonnets that Shakespeare means what he is saying, but as if he were anticipating our shadow of doubt that we might retain just because we find the constellation between our great poet and this young nobleman so extraordinary, he now addresses not the young man, not Time, or any other personified concept, but us: the outsider who looks in on all this and might feel tempted to lump these sonnets in with the generic output of other poets. No, he says: this is different. I am true in love and I do not write poetic hyperbole or eulogise in wildly inappropriate comparisons or exaggerations. I just write the truth and that truth is that my love is as beautiful as anyone.

Of course, it is impossible to test the veracity of that statement, not least since beauty is nowhere else so much as in the eye of the beholder. Of significance and therefore meaning for us though more than anything is the tone, which positions Shakespeare as a true lover and and truthful poet who is speaking to us directly. We need to, as always, be careful how much we are prepared to read into or at any rate take from these sonnets, but with this, coming from a man who has repeatedly now told the young man that he will live on in his, Shakespeare's, poetry, we are allowed to at least consider the possibility that Shakespeare is really thinking across the ages here.

We have no idea who reads this or any other of the sonnets at the time they are written. We can't even be sure – as we noted – whether the young man himself receives them. We do know that they are first mentioned in 1598 as 'circulating among friends', but we don't know which ones these sonnets are and we don't even know who exactly those friends are. What we also do know, though, and this directly from the words themselves, which – as we remind ourselves – is easily the most reliable source of any we have, is that Shakespeare in this poem addresses the reader or listener directly and says 'believe me' when I tell you this. Obviously, 'believe me' is an idiomatic turn of phrase, but its use here is still hardly an accident or coincidental.

The contention then is that whether Shakespeare is speaking to his friends, among whom some of his sonnets may or may not be circulating by the time he writes this particular one, or to us, as the readers in a foreseeable future when – because we can breathe and have eyes to see – his young love is still alive in his verse, we are effectively told to take him seriously. And while this is – in the current series and traditional sequence – the first time Shakespeare demands to be taken seriously, it certainly won't be the last. In fact the next few sonnets are just about to chart some of the quite turbulent ups and downs our poet is going through both with his love and his life...

Some editors have speculated that Shakespeare with 'that muse' may be referring to the 'rival poet' who makes his appearance later in the series when he seems to usurp Shakespeare's place as his young lover's favourite poet. As with so many other things concerning these poems, we cannot say with any certainty whether or not this is the case, but what mostly speaks against this idea is that the sonnets in which the 'rival poet' features are generally accepted as Sonnets 78 to 86 and that there is no concrete indication that Shakespeare here has a specific individual in mind. By some margin more likely therefore is that 'that muse' is simply a generic sideswipe at the kind of poet who indulges in the practices that Shakespeare so scornfully lists. Colin Burrow, Editor of the Oxford World's Classics edition of the Sonnets points out that by the time Shakespeare writes these sonnets, he is not the only one to criticise overly flowery language in poetry, and particularly highlights a book known as both Apology for Poetry and The Defence of Poetry by Shakespeare's contemporary Sir Philip Sidney as a primary example.

It is certainly interesting to note that Shakespeare delineates himself against what he emphatically considers bad poetry, and once again against fakery. And in this context the reference, directly following on from Sonnet 20, to a 'painted beauty' is telling.

We noted there and at least once earlier that Shakespeare does not hold women who wear heavy makeup in too high regard, and it may be worth observing at this juncture that the kind of makeup some women wore in the Elizabethan age – including the Queen herself – was not always exactly a subtle affair: often thick layers of quite literally 'face paint' were applied to cover up blemishes, the ravages of disease, and the signs of old age. Women who worked as courtesans – what today we would call sex workers – in an age before antibiotics and effective healthcare were particularly susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases, symptoms of which were facial blisters and lesions, among many others, and often these were simply covered up with makeup. So Shakespeare's disdain for 'painted beauty' compared to natural beauty may not be purely down to aesthetics. And he does close by stressing how his love – the young man – does not purpose to sell himself. In matters of 'love' and 'beauty', those whom we most commonly tend to associate with 'selling' are, indeed, sex workers.

What is perhaps most striking for us though is the sincerity of tone that comes with the third quatrain:

O let me, true in love, but truly write

And then believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother's child

This takes us onto a new and different level from where we were only a few sonnets ago. After the flourish of Sonnet 18 we had Shakespeare speak to Time itself, saying: "I forbid thee one most heinous crime," namely to carve "my love's fair brow,"

and we took note there how that was the first time we could not be in any doubt that Shakespeare was referring to the young man who receives these sonnets as his 'love'; in Sonnet 20 then he elaborates frankly and a little saucily on the fact that this love is in fact a man and calls him the "master-mistress of my passion."

Both of these are telling and we also felt we were given to believe by these two sonnets that Shakespeare means what he is saying, but as if he were anticipating our shadow of doubt that we might retain just because we find the constellation between our great poet and this young nobleman so extraordinary, he now addresses not the young man, not Time, or any other personified concept, but us: the outsider who looks in on all this and might feel tempted to lump these sonnets in with the generic output of other poets. No, he says: this is different. I am true in love and I do not write poetic hyperbole or eulogise in wildly inappropriate comparisons or exaggerations. I just write the truth and that truth is that my love is as beautiful as anyone.

Of course, it is impossible to test the veracity of that statement, not least since beauty is nowhere else so much as in the eye of the beholder. Of significance and therefore meaning for us though more than anything is the tone, which positions Shakespeare as a true lover and and truthful poet who is speaking to us directly. We need to, as always, be careful how much we are prepared to read into or at any rate take from these sonnets, but with this, coming from a man who has repeatedly now told the young man that he will live on in his, Shakespeare's, poetry, we are allowed to at least consider the possibility that Shakespeare is really thinking across the ages here.

We have no idea who reads this or any other of the sonnets at the time they are written. We can't even be sure – as we noted – whether the young man himself receives them. We do know that they are first mentioned in 1598 as 'circulating among friends', but we don't know which ones these sonnets are and we don't even know who exactly those friends are. What we also do know, though, and this directly from the words themselves, which – as we remind ourselves – is easily the most reliable source of any we have, is that Shakespeare in this poem addresses the reader or listener directly and says 'believe me' when I tell you this. Obviously, 'believe me' is an idiomatic turn of phrase, but its use here is still hardly an accident or coincidental.

The contention then is that whether Shakespeare is speaking to his friends, among whom some of his sonnets may or may not be circulating by the time he writes this particular one, or to us, as the readers in a foreseeable future when – because we can breathe and have eyes to see – his young love is still alive in his verse, we are effectively told to take him seriously. And while this is – in the current series and traditional sequence – the first time Shakespeare demands to be taken seriously, it certainly won't be the last. In fact the next few sonnets are just about to chart some of the quite turbulent ups and downs our poet is going through both with his love and his life...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!