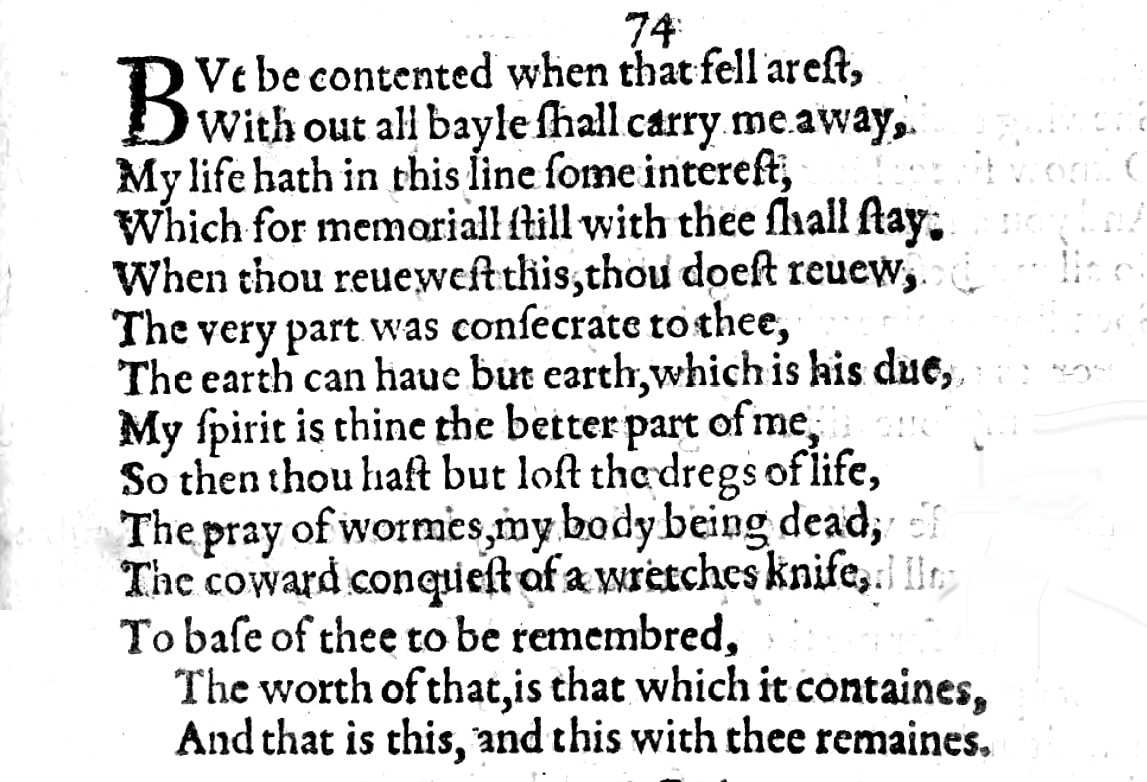

Sonnet 74: But Be Contented When That Fell Arrest

|

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away. My life hath in this line some interest, Which for memorial still with thee shall stay: When thou reviewest this, thou dost review The very part was consecrate to thee; The earth can have but earth, which is his due: My spirit is thine, the better part of me. So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life, The prey of worms, my body being dead; The coward conquest of a wretch's knife, Too base of thee to be remembered. The worth of that is that which it contains And that is this, and this with thee remains. |

|

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away. |

But be content or satisfied or even 'happy', as in 'happy enough' or at least 'not unhappy', when death comes and without any chance of reprieve carries me away.

The last time we came across the adjective 'fell' was in Sonnet 64: When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced The rich, proud cost of outworn, buried age, And the definition there as here is "of terrible evil or ferocity; deadly" (Oxford Languages), and so that 'fell arrest' is the deadly cessation of life – death – whereby the meaning we more readily now associate with 'arrest', the taking into custody or captivity of a person, may also be deliberately hinted at, since it is this arrest that carries me away without all bail, 'bail' of course being a legal term, something Shakespeare is often quite fond of. |

|

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay: |

And here comes the explanation why the recipient of this sonnet should be content upon my, the poet's, death: because my life has some interest, for which here read legal share and therefore value, and thus, by extension, purpose or meaning that is contained in this line of verse that I am writing for you right now, and this 'interest' – or value, or purpose, or meaning – shall remain with you forever.

'Still' here as on many other occasions, means 'always' or, with a vector into the future, 'forever'. |

|

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee; |

When you look at and read this line, or here probably more broadly this sonnet, or even these sonnets, you read the very part of my life that has been consecrated to you, in other words, you are looking at that part of me that I have dedicated to you, namely, as will become clear in a moment, my spirit, my essence, my worth.

'Consecrate' is an older form of 'consecrated', and much has been made and continues to be made of the choice of this word, which, over the centuries, people have suggested would have had the potential to come across as borderline or indeed sacrilegious at the time. After all, in Christian liturgy, bread and wine is 'consecrated' to become the body and blood of Jesus; bishops and priests are 'consecrated' when they are ordained, and places of worship are declared holy by 'consecration'. So for the poet to 'consecrate' his spirit or essence to the young man comes close to tying himself into a sacred union before God, otherwise understood as marriage, and that may well have been considered quite a daring move on Shakespeare's part at the time. But it is not the only occasion when he does this, as we shall see, with one of the most famous sonnets of them all, a fair bit further down the line in the series. |

|

The earth can have but earth, which is his due:

|

The earth can only have my body, which is what is due to the earth, since – as we noted very recently – ashes go back to ashes, dust goes back to dust; we are made of the earth and we return to the earth and amalgamate with it to become one again.

'His' as so often, refers not to a person but to a thing, here the earth. |

|

My spirit is thine, the better part of me.

|

But my spirit belongs to you, and it is the better part of me.

Note here that for the line to scan, 'spirit' is pronounced as one syllable: sp'rit. |

|

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead; |

So then, when I am dead, you have only really lost the dregs of my life, meaning by definition the most worthless remains, which when and because my body is dead, turn into the prey of the worms that will eat it...

|

|

The coward conquest of a wretch's knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered. |

...what you have lost is that which amounts to the cowardly conquest of a wretch's knife, and this is altogether too base or common and therefore worthless for you to even remember it.

'Coward conquest' is another instance of hypallage, the rhetorical device in which an adjective, here 'coward' for 'cowardly' is applied to one noun, here 'conquest', when it really belongs to another noun in the same sentence, here the 'wretch' who carries a knife and with it conquers the person he stabs and murders. We've discussed this a bit also with Sonnet 62. And the person carrying the knife is a wretch because they are a coward, and they are a coward because the implication is that this is a mean murder scenario, not an open fight or battle, so the idea is of somebody being stabbed in the back or when they are defenceless, for example. One person in the close orbit of William Shakespeare who became the coward conquest of a wretch's knife was his exact contemporary, Christopher Marlowe, who was killed in Deptford on 30th May 1593, aged 29 under mysterious and to this day never resolved circumstances. Shakespeare was deeply influenced by Marlowe's work and he may well have been friends with him, or if not friends then acquaintances: the London scene of poets and playwrights was close-knit and small and so he certainly knew of him and of his untimely death. Whether or not this is a reference to Marlowe's demise we can't know, what we do know is that Shakespeare does make reference to him and to his death in at least one of his plays, As You Like It, where he also quotes him directly. And therefore, as is so often the case, this is but a possibility. It is no more, but it is also no less... |

|

The worth of that is that which it contains

And that is this, and this with thee remains. |

The actual worth of that body of mine which you have lost is that which it contains, and that is this poem because this poem expresses my spirit, my essence, my soul, and this poem will remain with you.

|

Sonnet 74 continues the argument from Sonnet 73, and now reflects on what will happen when I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am dead: my body will be buried and return to earth, but my spirit will live on in this poetry that I write for you, the young man, which is why the loss you experience at my death will be insignificant: it only entails my passing physical presence, not my essence. In this, the poem proves prophetic not only in relation to the young lover, but also in relation to the world as a whole, since we still very much possess the spirit of William Shakespeare in his writing, and it also flatly contradicts his own pronouncements made in the pair just preceding this one, Sonnets 71 & 72, in which he – somewhat disingenuously we thought then – presented his poetry as something that is supposed to be 'nothing worth'.

Here are Sonnets 73 & 74 together, as they really belong:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou seest the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self that seals up all in rest;

In me thou seest the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away.

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay:

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee;

The earth can have but earth, which is his due:

My spirit is thine, the better part of me.

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead;

The coward conquest of a wretch's knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The worth of that is that which it contains

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

What is perhaps most striking about this couple of sonnets – apart from their compositional beauty – is their absolute integrity. When in Sonnets 71 & 72 we found it hard to believe everything Shakespeare was saying and felt strongly that we needed to take some of his statements with a pinch of salt, or at least read them as the conveyance of opinions held by other people that hurt the poet keenly but that he hardly truly shares, in Sonnets 73 & 74 we can readily believe every word, and that is the case with Sonnet 74 even more emphatically than with Sonnet 73.

There, the portrayal of the poet as an old man for us today is a little problematic, but we have dealt with this issue, briefly in our last episode and, as mentioned there, several times before. It is not something that needs to trouble us. And the only note of potential dissonance with immediately obvious veracity is struck in the closing couplet, where we did wonder whether Will is simply wishing things were so, even if they maybe aren't? But there we found ample reason to accept his declaration as an – at least at that moment – honestly experienced and understood reality. And certainly, the couplet, as the entire poem, is devoid of irony or sarcasm, quite unlike Sonnets 71 & 72.

Sonnet 74 now advances this baring of Shakespeare's soul almost to the level of a testament: I leave you my spirit. It is the best part of me, and it is "consecrate to thee." There could hardly be a more emphatic, more fulsome, indeed more generous gift and legacy. And it is a dedicated bestowment to this recipient. Because, yes, we now all have this poetry: the legacy of William Shakespeare today is owned and shared by and with the world, no-one has title to it; it is so much in our language, in our culture that it has become part of our very own being, but these two sonnets, as well as the previous two, as well as many, many of these poems we have looked at so far, were written for, to, and about a person Shakespeare loved. As you will know if you have listened to more than the odd episode of this podcast before, debates rage, or if not rage then certainly rumble, over who this person is, or possibly who these people are, and we will talk in a great deal more detail about this particular question, but for the time-being, let us just note and register that in this couple of sonnets, William Shakespeare makes two things categorically clear for us, should we ever have felt reason to doubt them:

One, the value of my life, my whole purpose is my writing. People may say what they want about me, but that is where my spirit, my essence, my soul is contained: in this line. My poetry. And I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, do not hesitate to extend this to the totality of these sonnets, which, as I have argued on multiple occasions, come straight from the heart, and in a wider sense also to the body of work Shakespeare leaves behind.

Not everything a professional writer brings forth is deeply personal: a playwright who has to make a living may well produce a script now and then that just needs to get bums on seats, and Shakespeare as well as an artist is a businessman, and a good one at that. But any creative person who can say that their spirit lives in the line they write will put something of themselves into their writing always. In some cases more, in other cases less. In a philosophical tragedy like Hamlet – named almost directly after his own son – a great deal, in a gory crowd pleaser like Titus Andronicus perhaps quite a bit less. In the sonnets, all of Shakespeare is contained. They – setting aside the 17 Procreation Sonnets at the beginning and the two allegorical poems at the end – have no purpose other than to communicate Shakespeare to himself and to his loves. And here I use the plural because of course we know of at least one other person for certain that some of the sonnets are addressed to or about, and that is the woman who gets referred to as The Dark Lady, whom we haven't properly met yet but will encounter in due course.

And herein lies the second thing we can take from these two sonnets without needing to question it much further: the person to whom these two poems are directly addressed, who we have no reason not to believe is the same person as the person to whom Sonnets 71 & 72 are addressed, really matters to Shakespeare. This may seem like stating the obvious, because isn't that the gist of all these sonnets, that the person they are written for matters to Shakespeare? Yes, but note the distinction between a person who matters enough for me, the poet, William Shakespeare, to write a sonnet for, and a person who matters enough for me, the poet, William Shakespeare to tell them in my sonnet that my worth, my spirit, my soul is consecrate to them.

I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, would argue – and I know with this I am not at all alone but I do stand in contradiction to the view of some highly respected scholars, also by me, including, among others, my guests on this podcast, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells – that this is not something you do to many people. Of course, we need to be careful, because these are sonnets and sonnets are by origin a form of love poetry and in love poetry people say things that they don't mean literally. But this is not a poem that comes along as a series of cliches or tropes. The one line that comes close to one is "The earth can have but earth, which is his due," which references The Common Book of Prayer with its "earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust," which in turn borrows from the Bible, Ecclesiastes 12.7: "Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was, and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it." (King James Version)

But look what Shakespeare does with this line, which could be argued to be a commonplace: he acknowledges that the earth will get back that which is its due, namely earth, which is my body, but my spirit, which the scriptures where this thought stems from return to God who gave it, Shakespeare consecrates to his lover. Again, let us be cautious with what we read into this, but this is not a casual throwaway remark.

Earlier, we noted the meanings of the word 'consecrate' and how potentially contentious it might be at the time, and we likened this to an act of union that could be compared to a marriage. Now Shakespeare when he writes this is married for sure, to Anne, his wife in Stratford-upon-Avon, but nobody seriously argues that these poems here are addressed to and written for her. We know he has at least one mistress who has already been mentioned in the sonnets, and at least the one male lover to whom he addresses, or about whom he writes all or most of these sonnets so far, and so we can't even argue that he takes marriage to be an inviolable sacred act of exclusive dedication to one person only.

But seeing that we have yet to meet with one strong indicator that Shakespeare has switched his affection from one young lover to another young lover, and noting the depth and sincerity of his language here, we have, if not proof – because no proof exists – seriously strong, highly compelling, soundly reasonable grounds to say: this person, the man whom Sonnets 73 & 74 are written for, matters substantially to Shakespeare: this is not a short-lived, superficial affair, this is not a lover among many, this is not a dalliance or a frivolous fling, this is – just as we thought we were able to sense for some time now – a deeply felt, ongoing love, which, however, and this is partly what makes these two poems so incredibly powerful, cannot be forever. Not only because ultimately the poet will die and all that remains will be his spirit, which does not in its entirety and without trace return to God who gave it, but which stays with the young lover and through him with us, but also because the young lover loves someone he "must leave ere long." This is an Elizabethan reality: if the young man is even remotely similar in status and character to the profile we have been drawing up about him from these sonnets, then this is an inescapable necessity, there is no long-term future for him and Will 'together'. He will have to pursue his social, economic, and also political obligations in the society he is part of, and so these two sonnets. which find themselves nearly halfway in a collection that is without a doubt also a series of sequences, are pivotal: we are here at a turning point.

And speaking of turning points: there is a fascinating little numerical detail: if we look at the 126 sonnets that are traditionally regarded as The Fair Youth Sonnets, and for the moment disregard again the first 17 Procreation Sonnets, since they clearly are motivated not by any deep feelings of Shakespeare's but most likely by a commissioned task, then with Sonnet 73 we enter the third third or, if you like, third 'act' of the 'story' – and I use this word here, contested so much by some, wisely – with the young man. And whether or not these sonnets are in the right order, whether or not they do chart one principal relationship, and whether or not they are therefore strictly sequential or, as most people agree, at least sporadically out of sequence – what follows next very much feels like the third act in a drama of passion, power, and possession, and the key plot point, if this were written to formula, is just around the corner with the entrance of a new and by William Shakespeare wholly unwelcome character who changes the dynamic completely: the rival poet.

Before then though, we have two sonnets that serve a bit as a reality check for Shakespeare in his assessment of his relationship with the young lover, and then Sonnet 77, which is virtually unique in its almost didactic aloofness, and marks a rest or a pause or even, if you like, a calm, just before the storm of disaster strikes.

Here are Sonnets 73 & 74 together, as they really belong:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou seest the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self that seals up all in rest;

In me thou seest the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away.

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay:

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee;

The earth can have but earth, which is his due:

My spirit is thine, the better part of me.

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead;

The coward conquest of a wretch's knife,

Too base of thee to be remembered.

The worth of that is that which it contains

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

What is perhaps most striking about this couple of sonnets – apart from their compositional beauty – is their absolute integrity. When in Sonnets 71 & 72 we found it hard to believe everything Shakespeare was saying and felt strongly that we needed to take some of his statements with a pinch of salt, or at least read them as the conveyance of opinions held by other people that hurt the poet keenly but that he hardly truly shares, in Sonnets 73 & 74 we can readily believe every word, and that is the case with Sonnet 74 even more emphatically than with Sonnet 73.

There, the portrayal of the poet as an old man for us today is a little problematic, but we have dealt with this issue, briefly in our last episode and, as mentioned there, several times before. It is not something that needs to trouble us. And the only note of potential dissonance with immediately obvious veracity is struck in the closing couplet, where we did wonder whether Will is simply wishing things were so, even if they maybe aren't? But there we found ample reason to accept his declaration as an – at least at that moment – honestly experienced and understood reality. And certainly, the couplet, as the entire poem, is devoid of irony or sarcasm, quite unlike Sonnets 71 & 72.

Sonnet 74 now advances this baring of Shakespeare's soul almost to the level of a testament: I leave you my spirit. It is the best part of me, and it is "consecrate to thee." There could hardly be a more emphatic, more fulsome, indeed more generous gift and legacy. And it is a dedicated bestowment to this recipient. Because, yes, we now all have this poetry: the legacy of William Shakespeare today is owned and shared by and with the world, no-one has title to it; it is so much in our language, in our culture that it has become part of our very own being, but these two sonnets, as well as the previous two, as well as many, many of these poems we have looked at so far, were written for, to, and about a person Shakespeare loved. As you will know if you have listened to more than the odd episode of this podcast before, debates rage, or if not rage then certainly rumble, over who this person is, or possibly who these people are, and we will talk in a great deal more detail about this particular question, but for the time-being, let us just note and register that in this couple of sonnets, William Shakespeare makes two things categorically clear for us, should we ever have felt reason to doubt them:

One, the value of my life, my whole purpose is my writing. People may say what they want about me, but that is where my spirit, my essence, my soul is contained: in this line. My poetry. And I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, do not hesitate to extend this to the totality of these sonnets, which, as I have argued on multiple occasions, come straight from the heart, and in a wider sense also to the body of work Shakespeare leaves behind.

Not everything a professional writer brings forth is deeply personal: a playwright who has to make a living may well produce a script now and then that just needs to get bums on seats, and Shakespeare as well as an artist is a businessman, and a good one at that. But any creative person who can say that their spirit lives in the line they write will put something of themselves into their writing always. In some cases more, in other cases less. In a philosophical tragedy like Hamlet – named almost directly after his own son – a great deal, in a gory crowd pleaser like Titus Andronicus perhaps quite a bit less. In the sonnets, all of Shakespeare is contained. They – setting aside the 17 Procreation Sonnets at the beginning and the two allegorical poems at the end – have no purpose other than to communicate Shakespeare to himself and to his loves. And here I use the plural because of course we know of at least one other person for certain that some of the sonnets are addressed to or about, and that is the woman who gets referred to as The Dark Lady, whom we haven't properly met yet but will encounter in due course.

And herein lies the second thing we can take from these two sonnets without needing to question it much further: the person to whom these two poems are directly addressed, who we have no reason not to believe is the same person as the person to whom Sonnets 71 & 72 are addressed, really matters to Shakespeare. This may seem like stating the obvious, because isn't that the gist of all these sonnets, that the person they are written for matters to Shakespeare? Yes, but note the distinction between a person who matters enough for me, the poet, William Shakespeare, to write a sonnet for, and a person who matters enough for me, the poet, William Shakespeare to tell them in my sonnet that my worth, my spirit, my soul is consecrate to them.

I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, would argue – and I know with this I am not at all alone but I do stand in contradiction to the view of some highly respected scholars, also by me, including, among others, my guests on this podcast, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells – that this is not something you do to many people. Of course, we need to be careful, because these are sonnets and sonnets are by origin a form of love poetry and in love poetry people say things that they don't mean literally. But this is not a poem that comes along as a series of cliches or tropes. The one line that comes close to one is "The earth can have but earth, which is his due," which references The Common Book of Prayer with its "earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust," which in turn borrows from the Bible, Ecclesiastes 12.7: "Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was, and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it." (King James Version)

But look what Shakespeare does with this line, which could be argued to be a commonplace: he acknowledges that the earth will get back that which is its due, namely earth, which is my body, but my spirit, which the scriptures where this thought stems from return to God who gave it, Shakespeare consecrates to his lover. Again, let us be cautious with what we read into this, but this is not a casual throwaway remark.

Earlier, we noted the meanings of the word 'consecrate' and how potentially contentious it might be at the time, and we likened this to an act of union that could be compared to a marriage. Now Shakespeare when he writes this is married for sure, to Anne, his wife in Stratford-upon-Avon, but nobody seriously argues that these poems here are addressed to and written for her. We know he has at least one mistress who has already been mentioned in the sonnets, and at least the one male lover to whom he addresses, or about whom he writes all or most of these sonnets so far, and so we can't even argue that he takes marriage to be an inviolable sacred act of exclusive dedication to one person only.

But seeing that we have yet to meet with one strong indicator that Shakespeare has switched his affection from one young lover to another young lover, and noting the depth and sincerity of his language here, we have, if not proof – because no proof exists – seriously strong, highly compelling, soundly reasonable grounds to say: this person, the man whom Sonnets 73 & 74 are written for, matters substantially to Shakespeare: this is not a short-lived, superficial affair, this is not a lover among many, this is not a dalliance or a frivolous fling, this is – just as we thought we were able to sense for some time now – a deeply felt, ongoing love, which, however, and this is partly what makes these two poems so incredibly powerful, cannot be forever. Not only because ultimately the poet will die and all that remains will be his spirit, which does not in its entirety and without trace return to God who gave it, but which stays with the young lover and through him with us, but also because the young lover loves someone he "must leave ere long." This is an Elizabethan reality: if the young man is even remotely similar in status and character to the profile we have been drawing up about him from these sonnets, then this is an inescapable necessity, there is no long-term future for him and Will 'together'. He will have to pursue his social, economic, and also political obligations in the society he is part of, and so these two sonnets. which find themselves nearly halfway in a collection that is without a doubt also a series of sequences, are pivotal: we are here at a turning point.

And speaking of turning points: there is a fascinating little numerical detail: if we look at the 126 sonnets that are traditionally regarded as The Fair Youth Sonnets, and for the moment disregard again the first 17 Procreation Sonnets, since they clearly are motivated not by any deep feelings of Shakespeare's but most likely by a commissioned task, then with Sonnet 73 we enter the third third or, if you like, third 'act' of the 'story' – and I use this word here, contested so much by some, wisely – with the young man. And whether or not these sonnets are in the right order, whether or not they do chart one principal relationship, and whether or not they are therefore strictly sequential or, as most people agree, at least sporadically out of sequence – what follows next very much feels like the third act in a drama of passion, power, and possession, and the key plot point, if this were written to formula, is just around the corner with the entrance of a new and by William Shakespeare wholly unwelcome character who changes the dynamic completely: the rival poet.

Before then though, we have two sonnets that serve a bit as a reality check for Shakespeare in his assessment of his relationship with the young lover, and then Sonnet 77, which is virtually unique in its almost didactic aloofness, and marks a rest or a pause or even, if you like, a calm, just before the storm of disaster strikes.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!