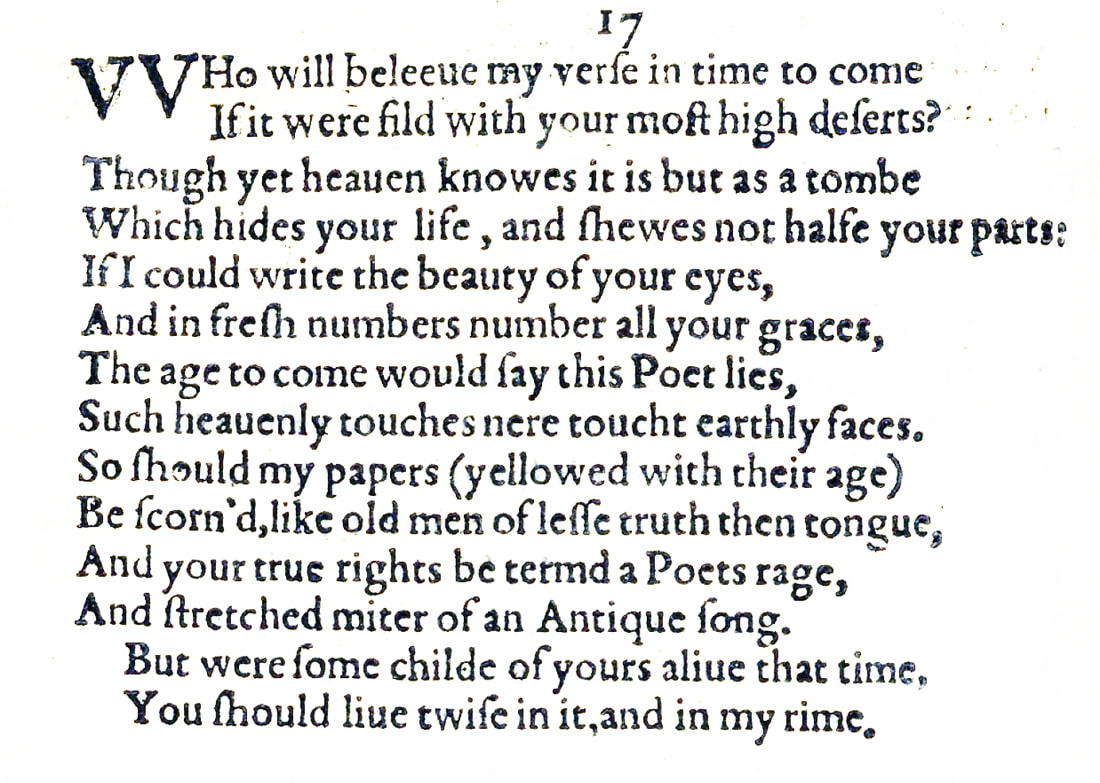

Sonnet 17: Who Will Believe My Verse in Time to Come

|

Who will believe my verse in time to come,

If it were filled with your most high deserts? Though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb Which hides your life and shows not half your parts. If I could write the beauty of your eyes, And in fresh numbers number all your graces, The age to come would say: 'this poet lies, Such heavenly touches never touched earthly faces'. So should my papers, yellowed with their age, Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue, And your true rights be termed a poet's rage, And stretched metre of an antique song. But were some child of yours alive that time, You should live twice: in it, and in my rhyme. |

|

Who will believe my verse in time to come,

If it were filled with your most high deserts? |

Who would believe my poetry in times to come, if it were to describe and portray you fully, with all your best qualities?

A slight difficulty for us arises from the fact that Shakespeare here uses a question in the future tense – 'who will believe my verse' – and combines it with a conditional clause. For us it would sound more natural to either say: 'who would believe my verse if it were filled', or indeed, 'who will believe my verse if it is filled.' The meaning though is pretty straightforward: the poet asks how anyone in the future will believe him if he praises the young man to the high level at which he deserves to be praised. |

|

Though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life and shows not half your parts. |

Although, heaven knows, it – my poetry – is nothing more than a tomb that buries your real self – "hides your life" – and is incapable of showing the world even half of what you really are.

Note that 'heaven' is pronounced with one syllable here: hea'en. |

|

If I could write the beauty of your eyes

And in fresh numbers number all your graces, |

If I were able to describe how beautiful your eyes are and find new ways to enumerate and list all your qualities...

|

|

The age to come would say: 'this poet lies,

Such heavenly touches never touched earthly faces'. |

...people of the future would say: 'this poet lies, no beauty as heavenly as this has ever been seen on a mere mortal's face.'

Heavenly here is pronounced as two syllables – hea'enly – and never as one: ne'er. |

|

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue, |

And so therefore the paper that I write on and that carries my poetry, once it has gone yellow through ageing, will be scorned and distrusted, much like old men who talk more than they truthfully say.

This "old men of less truth than tongue" is a fabulously compact way of saying that these old men thus referred to talk a lot, but that much of what they say is tall tales that have little or no foundation in truth. |

|

And your true rights be termed a poet's rage

|

And the praise and acclaim that you are genuinely entitled to – "your true rights," which would thus be contained in my poetry – would be called a poet's insane ramblings or rants...

|

|

And stretched metre of an antique song.

|

...and the strained and therefore unpleasing and untrustworthy verse of some old song or poem, in other words something that is not credible or reliable.

Stretched here has two syllables: stretch-èd. |

|

But were some child of yours alive that time

You should live twice: in it, and in my rhyme. |

But if at that point in the future a child of yours were alive, then you would be able to live twice: both in and through your child and also in my poem, even though I have just described it as inadequate.

|

The intricate, self-aware, and in places truly tender Sonnet 17 is the last one to advise the young man to produce some offspring, which makes it the last of the Procreation Sonnets, and it segues smoothly into entirely different and really new territory where William Shakespeare as the poet begins to take centre stage right next to the man he has been writing these sonnets for.

Superficially, it looks like Sonnet 17 may not be that different from the previous sixteen: the poet lays out an argument, saying if I could write you as perfectly as you really are then people reading this in the future would simply not believe me, they would say, this poet is a liar, he's making it all up idealising some figment of his imagination, and so you, who really are as beautiful and perfect as I would be saying would not get what is due to you, which is being recognised for your great qualities. If you were to produce a child, however, then this inadequacy of my poetry would not matter because you would live on in your son. So far that's pretty much what we've been hearing and therefore also expecting.

But listen to what happens underneath that surface: first of all there is this blatant contradiction between two different things that I, the poet, am saying about the potency of my poetry. On the one hand, I concede that my words are inadequate and that they are unable to relate you to future generations in any way that does you justice let alone keeps you alive, in fact I say that my poetry 'buries' your true self, on the other hand I conclude my argument not – as one might in that case expect – by saying, only a child of yours can make you live forever, as has been the tenor of the entire batch so far, but by saying that you, even after your death, can live twice: in your child and also in my rhyme.

If you know what's coming then you will detect in this a strong foreshadowing of the immeasurably famous Sonnet 18. And even if you don't know what's coming, then you do have something exquisite to look forward to...

The second thing that is yet again different and that marks an absolutely perceptible change in tone and therefore also in the dynamic between Shakespeare and the young man comes with the second quatrain, the second set of four lines: "If I could write the beauty of your eyes." There is a profound sense of wonder that is conveyed here, and you may recall how in Sonnet 14 we noted that I, the poet, am deriving my knowledge about the young man's future from his eyes, suggesting that – unless I am writing in an abstract void of poetic exuberance, and nothing so far has made that in the least bit plausible – I must have looked into the young man's eyes. This, only three sonnets later, would appear to confirm what we believed to detect as a distinct possibility there: that in the course of writing these sonnets for the young man I have only just got to know him and that it is during these last few stages of the Procreation Sonnets that I have come face-to-face with him and been properly smitten by him.

And as we are now leaving behind the Procreation Sonnets and enter the 'body proper' so to speak of the Fair Youth Sonnets, one principal question presents itself, quite apart from the even more towering question of 'who is this young man?', and that is this: are these Procreation Sonnets written to the same young man as those that follow, and then as we get into them, are those that follow all written to and for the same young man, or do they address different young men? This latter part of the question is something we will come to by and by, because, as you would by now expect from our entire approach to this examination of Shakespeare's sonnets, we will simply go by the words and listen to what the words tell us, and they will continue to tell us way more than we might have hoped.

So let us stick with this intermediate question then: is the young recipient of these first seventeen sonnets the same as the young man who receives the sonnets that follow immediately follow? And here Sonnet 17 can provide us, if not with an actual answer – because, as we keep reminding ourselves importantly and rightly: there are no definitive answers – then certainly with a strong and valid and therefore usable pointer. We have seen that – even allowing for all the many uncertainties and the host of possibilities that surround this entire body of work and specifically also these early sonnets – we have been on a trajectory, in which I, the poet, William Shakespeare, go from generic to specific, from remote to intimate, from restrained to bold. In other words: from professionally detached to personally involved. And Sonnet 17 sits right on this trajectory and actually paves the way in what a moment ago I called a smooth segue to what comes next: this sonnet anticipates exactly what comes next, and while here we don't want to talk about that yet, because it is for the next instalment, we do not need to be in any great doubt about the sequence actually continuing.

In Sonnet 17, I, the poet, do not introduce myself, I have been doing so gradually: I may or may not have dropped a hint at myself with my "self-willed" in Sonnet 6. In Sonnet 10, I ask the young man, any doubt disappears: "O change thy thought that I may change my mind," I say, and I conclude with the request: "Make thee another self for love of me." By Sonnet 12 I am firmly established as a presence in these poems of mine, and in fact I start out by speaking about myself: "When I do count the clock that tells the time:" I give my young man my view of his situation. Then, just one sonnet later, in Sonnet 13, I call him "dear my love," and in Sonnet 14 I again speak from my own perspective and I introduce the symbol and poetic trope of the eyes as stars, which is one most usually employed in relation to a loved one. Sonnet 15 again is as much about me as it is about you: "When I consider everything that grows," and "When I perceive that men as plants increase," and it goes a bold step further by introducing what cannot be described other than as an appreciable sauciness to the proceedings, topping things by saying: "And all in war with Time for love of you, / As he takes from you I engraft you new." Here I already bring my writing itself into the equation and I claim of it the power to imbue you with new life. In Sonnet 16 I then claw back a bit by rather disingenuously referring to "my barren rhyme" and indeed "my pupil pen," only to arrive at a truce, here now in Sonnet 17, between that "mightier way" also referred to in Sonnet 16 and the so supposedly inadequate writing of Sonnets 16 and 17, by saying that you now actually have two ways of living beyond your own lifetime: your child and my verse.

And the important thing we get from all this? There is no break. There is, instead, a continuation. There is nothing that points towards an entirely new book being started, everything points towards the story being continued with the same principals. As we leave behind the Procreation Sonnets and William Shakespeare's still largely unexplained preoccupation for a young man's succession, we start a new chapter in a continuing story, not a new story.

And this new chapter, as shortly we shall see, opens with a flourish in our next Sonnet: the celebrated, innumerably rendered and quoted and adapted and interpreted Sonnet 18, which does away with any concern about the young man – and I think we can now be pretty certain that it is the same young man – having children and instead asks the immortal question: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?"

Superficially, it looks like Sonnet 17 may not be that different from the previous sixteen: the poet lays out an argument, saying if I could write you as perfectly as you really are then people reading this in the future would simply not believe me, they would say, this poet is a liar, he's making it all up idealising some figment of his imagination, and so you, who really are as beautiful and perfect as I would be saying would not get what is due to you, which is being recognised for your great qualities. If you were to produce a child, however, then this inadequacy of my poetry would not matter because you would live on in your son. So far that's pretty much what we've been hearing and therefore also expecting.

But listen to what happens underneath that surface: first of all there is this blatant contradiction between two different things that I, the poet, am saying about the potency of my poetry. On the one hand, I concede that my words are inadequate and that they are unable to relate you to future generations in any way that does you justice let alone keeps you alive, in fact I say that my poetry 'buries' your true self, on the other hand I conclude my argument not – as one might in that case expect – by saying, only a child of yours can make you live forever, as has been the tenor of the entire batch so far, but by saying that you, even after your death, can live twice: in your child and also in my rhyme.

If you know what's coming then you will detect in this a strong foreshadowing of the immeasurably famous Sonnet 18. And even if you don't know what's coming, then you do have something exquisite to look forward to...

The second thing that is yet again different and that marks an absolutely perceptible change in tone and therefore also in the dynamic between Shakespeare and the young man comes with the second quatrain, the second set of four lines: "If I could write the beauty of your eyes." There is a profound sense of wonder that is conveyed here, and you may recall how in Sonnet 14 we noted that I, the poet, am deriving my knowledge about the young man's future from his eyes, suggesting that – unless I am writing in an abstract void of poetic exuberance, and nothing so far has made that in the least bit plausible – I must have looked into the young man's eyes. This, only three sonnets later, would appear to confirm what we believed to detect as a distinct possibility there: that in the course of writing these sonnets for the young man I have only just got to know him and that it is during these last few stages of the Procreation Sonnets that I have come face-to-face with him and been properly smitten by him.

And as we are now leaving behind the Procreation Sonnets and enter the 'body proper' so to speak of the Fair Youth Sonnets, one principal question presents itself, quite apart from the even more towering question of 'who is this young man?', and that is this: are these Procreation Sonnets written to the same young man as those that follow, and then as we get into them, are those that follow all written to and for the same young man, or do they address different young men? This latter part of the question is something we will come to by and by, because, as you would by now expect from our entire approach to this examination of Shakespeare's sonnets, we will simply go by the words and listen to what the words tell us, and they will continue to tell us way more than we might have hoped.

So let us stick with this intermediate question then: is the young recipient of these first seventeen sonnets the same as the young man who receives the sonnets that follow immediately follow? And here Sonnet 17 can provide us, if not with an actual answer – because, as we keep reminding ourselves importantly and rightly: there are no definitive answers – then certainly with a strong and valid and therefore usable pointer. We have seen that – even allowing for all the many uncertainties and the host of possibilities that surround this entire body of work and specifically also these early sonnets – we have been on a trajectory, in which I, the poet, William Shakespeare, go from generic to specific, from remote to intimate, from restrained to bold. In other words: from professionally detached to personally involved. And Sonnet 17 sits right on this trajectory and actually paves the way in what a moment ago I called a smooth segue to what comes next: this sonnet anticipates exactly what comes next, and while here we don't want to talk about that yet, because it is for the next instalment, we do not need to be in any great doubt about the sequence actually continuing.

In Sonnet 17, I, the poet, do not introduce myself, I have been doing so gradually: I may or may not have dropped a hint at myself with my "self-willed" in Sonnet 6. In Sonnet 10, I ask the young man, any doubt disappears: "O change thy thought that I may change my mind," I say, and I conclude with the request: "Make thee another self for love of me." By Sonnet 12 I am firmly established as a presence in these poems of mine, and in fact I start out by speaking about myself: "When I do count the clock that tells the time:" I give my young man my view of his situation. Then, just one sonnet later, in Sonnet 13, I call him "dear my love," and in Sonnet 14 I again speak from my own perspective and I introduce the symbol and poetic trope of the eyes as stars, which is one most usually employed in relation to a loved one. Sonnet 15 again is as much about me as it is about you: "When I consider everything that grows," and "When I perceive that men as plants increase," and it goes a bold step further by introducing what cannot be described other than as an appreciable sauciness to the proceedings, topping things by saying: "And all in war with Time for love of you, / As he takes from you I engraft you new." Here I already bring my writing itself into the equation and I claim of it the power to imbue you with new life. In Sonnet 16 I then claw back a bit by rather disingenuously referring to "my barren rhyme" and indeed "my pupil pen," only to arrive at a truce, here now in Sonnet 17, between that "mightier way" also referred to in Sonnet 16 and the so supposedly inadequate writing of Sonnets 16 and 17, by saying that you now actually have two ways of living beyond your own lifetime: your child and my verse.

And the important thing we get from all this? There is no break. There is, instead, a continuation. There is nothing that points towards an entirely new book being started, everything points towards the story being continued with the same principals. As we leave behind the Procreation Sonnets and William Shakespeare's still largely unexplained preoccupation for a young man's succession, we start a new chapter in a continuing story, not a new story.

And this new chapter, as shortly we shall see, opens with a flourish in our next Sonnet: the celebrated, innumerably rendered and quoted and adapted and interpreted Sonnet 18, which does away with any concern about the young man – and I think we can now be pretty certain that it is the same young man – having children and instead asks the immortal question: "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?"

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!