Sonnet 28: How Can I Then Return in Happy Plight

|

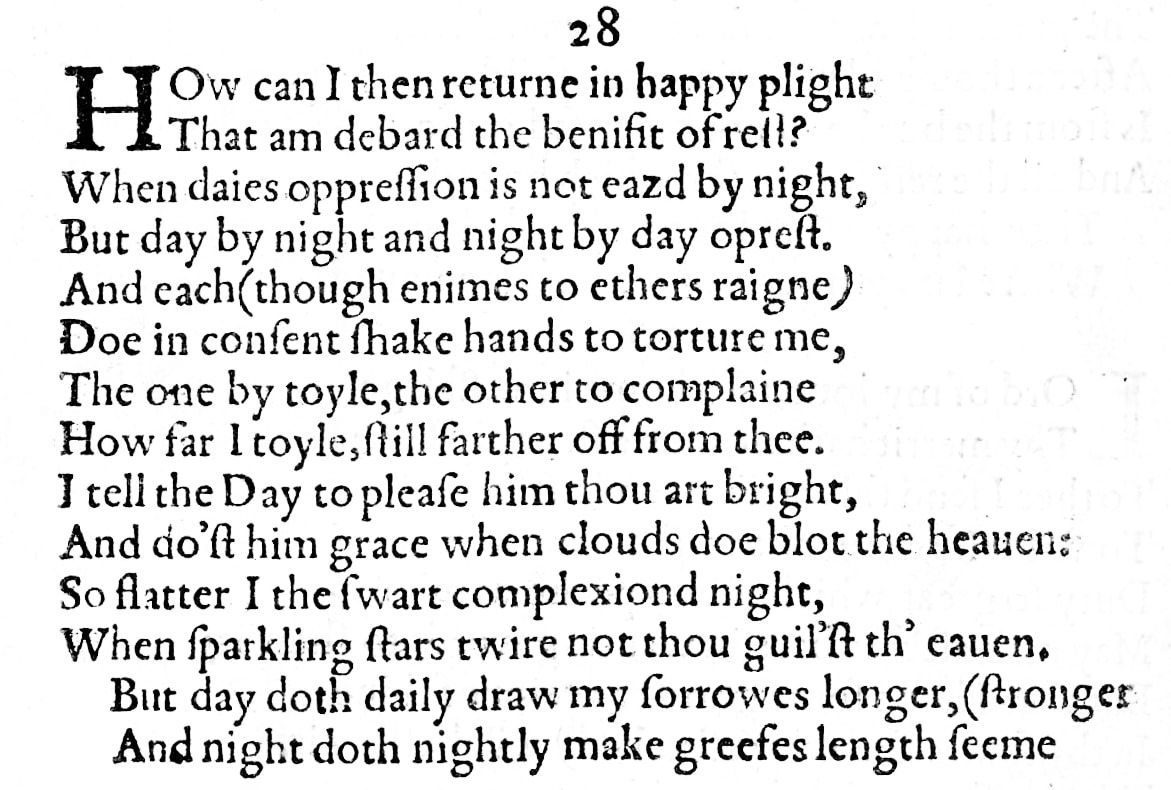

How can I then return in happy plight,

That am debarred the benefit of rest? When day's oppression is not eased by night, But day by night, and night by day oppressed, And each, though enemies to either's reign, Do in consent shake hands to torture me: The one by toil, the other to complain How far I toil, still farther off from thee. I tell the day to please him: 'thou art bright, And dost him grace', when clouds do blot the heaven; So flatter I the swart-complexioned night, When sparkling stars twire not: 'thou gildst the even'. But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger. |

|

How can I then return in happy plight

That am debarred the benefit of rest? |

The sonnet continues from Sonnet 27 and asks: everything said there – with my body being worn out during the day and my mind kept reeling during the night – how can I then return from my bed and start a new day in a happy disposition, when I am so denied the benefit of rest?

'Plight' here has a meaning of 'state' or 'condition' quite generally, rather than, as we would use it today, one of a dangerous or difficult situation, although the juxtaposition of 'happy' with 'plight', knowing Shakespeare, may well be deliberate. |

|

When day's oppression is not eased by night

But day by night and night by day oppressed, |

When it is the case that the strains that are put on me during the day are not eased by a good night's sleep, but in fact I am further weighed down by the agitation of my mind during the night, and then the next day, work and travel continues, adding further to my weariness.

The day is 'oppressed' by night, because night does not offer any relief for the exertions of the daytime, and night is 'oppressed' by day, because the day of course similarly does not offer any respite from the restlessness of the night. |

|

And each, though enemies to either's reign

Do in consent shake hands to torture me: |

And although day and night are opposites which cannot coexist at the same time but have to fight each other for dominance, one following the other in an eternal cycle, they shake hands in agreement on a pact to torture me:...

|

|

The one by toil, the other to complain

How far I toil, still farther off from thee. |

...one of them – day – tortures me with the 'toil', for which here again clearly read exhausting travel as much as the work that goes with the travel or that the travel is for, the other – night – tortures me by giving me time to reflect and therefore bemoan or complain to myself about how far away I travel from you, and the longer this goes on the further away I find myself from you.

|

|

I tell the Day to please him: 'thou art bright

And dost him grace,' when clouds to blot the heaven; |

This third quatrain offers two quite categorically different interpretations. What is clear is that the Day here and then in the following two lines the Night are both personified and addressed by me, the poet, as if they were people.

Most editors assume that I, the poet, talk to first Day and then to Night about the young man. If that is the case, then here I am saying to the Day: you, my young lover, are metaphorically bright, because you are beautiful, and you, with your beauty, grace the day, even when the sun isn't shining, but clouds are in the sky. And I do this to please the day, meaning to make the day more pleasant and thus more bearable to me. To the same effect – to please the Day, and thus make it more bearable to me – the line can also be read as direct speech addressing Day itself: I say to the Day: you, the day, are bright and you do him, my lover, grace, meaning you, with your beauty, remind me of him and honour him, and I say this to you even when you, the day, are not in fact bright, but are clouded over with bad weather. Some editors go as far as suggesting that the 'to please him' belongs to what you, my lover do, reading the line as: I tell the Day that you, in order to please him, the day, are bright and do him grace, even when clouds darken the sky. Note that here we have a choice of pronouncing 'heaven' either as two syllables, resulting in a feminine line ending, or as one syllable, 'hea'n', resulting in a masculine line ending. The same will then simply have to be applied to the rhyming 'even' below. |

|

So flatter I the swart-complexioned Night

When sparkling stars twire not: 'Thou gildst the even.' |

In the same way I also flatter the black Night – 'swart-comlexioned' means having a black complexion – that you gild and therefore beautify and grace the evening, even when there are no stars in the sky.

Similarly, the line can be read in two ways. Either as I, the poet, saying to the Night: you, my lover, make the evening golden, even when there are no stars in the sky because the night sky is overcast, or as, I, the poet saying to the Night, you, the Night, make the evening golden for me even when there are no stars in the sky. What slightly favours the latter – though it has to be said less common – interpretation, the one where I, the poet, talk to first Day and then Night, addressing them directly, are the two qualifying statements 'to please him' for the Day and 'flatter' for the Night. It would seem a more obvious way of flattering someone to compliment them directly rather than by saying to them that somebody else is gilding them. But this is far from conclusive. And in Sonnet 27, which this clearly and unmistakably follows on from, I compared the young man to a jewel that can make the dark night beautiful, so drawing a firm conclusion is virtually impossible. And a few sonnets back, in Sonnet 20 I told the young man that he is 'gilding the object' whereupon his eye gazes. Here as elsewhere we may have to entertain the possibility that Shakespeare is aware of the double meaning and delights in his own dexterity to give us a deliberately ambiguous quatrain, but the sense we get remains largely the same: I try to put on a brave face and make my day and my night bearable by reminding myself of how beautiful you are. |

|

But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer

|

But every day draws out my sorrow for being away from you and also, as I said just a little earlier, every day takes me geographically further away from you and thus puts a greater distance and therefore a longer road home between us...

|

|

And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger.

|

...and every night deepens my grief for being away from you.

It is tempting here to emend the Quarto Edition's 'length' for 'strength' and make the line read: And night doth nightly make grief's strength seem stronger. But even if that should appeal, it isn't strictly necessary for the line to make sense, and as some editors point out, the focus on both distance and duration that 'length' offers is possibly more elegant than reinforcing 'strength' with 'stronger'. In any case though, my approach is to go by the words that we have and while we must allow for the possibility of some mistakes having crept in – and in some cases these are so obvious that, as we have seen, they have to be emended – doing so absolutely needs to be a last resort. For the most part and wherever possible, the assumption surely has to be that Shakespeare knew what he was doing and that we do not need to 'improve' on his writing... |

Sonnet 28 continues on from Sonnet 27 and develops the thought further, elaborating on the ways day and night appear to conspire to make William Shakespeare's struggling life a misery as he travels, away from his young lover. While it thus does not tell us anything that is in that sense new, it produces a layered internal dialogue that gives us a great sense of the poet's state of mind and disposition of heart.

To fully get this sense of absence, longing, and growing unease of lingering despair, the two poems of course have to be taken together:

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired,

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind when body's work's expired,

For then my thoughts, from far where I abide,

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see,

Save that my soul's imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new.

Lo, thus by day my limbs, by night my mind

For thee and for myself no quiet find.

How can I then return in happy plight,

That am debarred the benefit of rest?

When day's oppression is not eased by night,

But day by night, and night by day oppressed,

And each, though enemies to either's reign,

Do in consent shake hands to torture me:

The one by toil, the other to complain

How far I toil, still farther off from thee.

I tell the day to please him: 'thou art bright,

And dost him grace', when clouds do blot the heaven;

So flatter I the swart-complexioned night,

When sparkling stars twire not: 'thou gildst the even'.

But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer

And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger.

It could be argued, perhaps, that these two sonnets are among the least spectacular ones we have met so far. And certainly, there is a subdued weariness, yes, but also an underlying anguish that seems to seep through. Only four lines in Sonnet 27 concern themselves with the young man and there make a gentle, understated simile with a jewel that endows a dark and gloomy night with new beauty. And it is this same sense of light that is then picked up in Sonnet 28, where the melancholy grey of a cloudy day and the pervasive umbra of a starless night are lifted somewhat – but only somewhat – by being able to talk about the love who is left behind. And here, as we have seen, it isn't even entirely clear who is doing what to whom: am I trying to please the day and flattering the night by telling them things they are not, namely bright and gilding the evening, and you, the young man who is not here with me, are really principally the reason for my need to attempt to cheer myself up in this way? Or am I doing the same – trying to please the day and flatter the night – by talking about you.

Maybe the greatest insight we glean from these two sonnets then is not so much in the words and their direct or indirect meaning, but in this ambiguity and the lacklustre spirit they convey. If you have ever been tired, worn out, underpowered, away from home, and all the while missing someone badly, the tone and atmosphere of Sonnets 27 and 28, but particularly of Sonnet 28, will be all too familiar. It is, what in today's language we – perhaps a bit lazily and as an at times inappropriate shorthand – call being 'depressed'. Certainly, these two poems do not burst with any joy, or energy, or drive, or even, for that matter, great emotional gushing of love. They are subdued, somewhat diffuse so as not to say muddled, and they cling on to the thought and the image of the young man but barely seem to succeed. They are written in a frame of mind that is utterly low. Hearing these sonnets, we want to give our Will a big hug and say, chin up, this too shall pass. And it does. But not before William Shakespeare finds fresh form and funnels his despair into one of the most triumphant compositions in the canon: Sonnet 29...

To fully get this sense of absence, longing, and growing unease of lingering despair, the two poems of course have to be taken together:

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired,

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind when body's work's expired,

For then my thoughts, from far where I abide,

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see,

Save that my soul's imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new.

Lo, thus by day my limbs, by night my mind

For thee and for myself no quiet find.

How can I then return in happy plight,

That am debarred the benefit of rest?

When day's oppression is not eased by night,

But day by night, and night by day oppressed,

And each, though enemies to either's reign,

Do in consent shake hands to torture me:

The one by toil, the other to complain

How far I toil, still farther off from thee.

I tell the day to please him: 'thou art bright,

And dost him grace', when clouds do blot the heaven;

So flatter I the swart-complexioned night,

When sparkling stars twire not: 'thou gildst the even'.

But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer

And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger.

It could be argued, perhaps, that these two sonnets are among the least spectacular ones we have met so far. And certainly, there is a subdued weariness, yes, but also an underlying anguish that seems to seep through. Only four lines in Sonnet 27 concern themselves with the young man and there make a gentle, understated simile with a jewel that endows a dark and gloomy night with new beauty. And it is this same sense of light that is then picked up in Sonnet 28, where the melancholy grey of a cloudy day and the pervasive umbra of a starless night are lifted somewhat – but only somewhat – by being able to talk about the love who is left behind. And here, as we have seen, it isn't even entirely clear who is doing what to whom: am I trying to please the day and flattering the night by telling them things they are not, namely bright and gilding the evening, and you, the young man who is not here with me, are really principally the reason for my need to attempt to cheer myself up in this way? Or am I doing the same – trying to please the day and flatter the night – by talking about you.

Maybe the greatest insight we glean from these two sonnets then is not so much in the words and their direct or indirect meaning, but in this ambiguity and the lacklustre spirit they convey. If you have ever been tired, worn out, underpowered, away from home, and all the while missing someone badly, the tone and atmosphere of Sonnets 27 and 28, but particularly of Sonnet 28, will be all too familiar. It is, what in today's language we – perhaps a bit lazily and as an at times inappropriate shorthand – call being 'depressed'. Certainly, these two poems do not burst with any joy, or energy, or drive, or even, for that matter, great emotional gushing of love. They are subdued, somewhat diffuse so as not to say muddled, and they cling on to the thought and the image of the young man but barely seem to succeed. They are written in a frame of mind that is utterly low. Hearing these sonnets, we want to give our Will a big hug and say, chin up, this too shall pass. And it does. But not before William Shakespeare finds fresh form and funnels his despair into one of the most triumphant compositions in the canon: Sonnet 29...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!