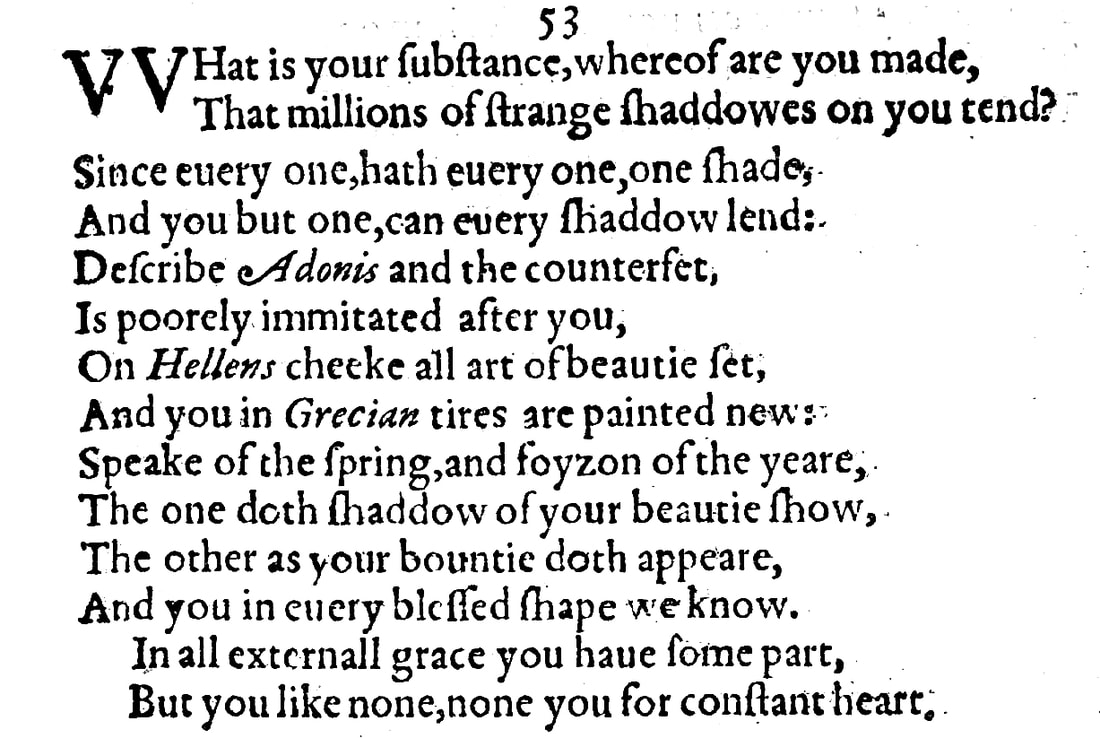

Sonnet 53: What Is Your Substance, Whereof Are You Made

|

What is your substance, whereof are you made,

That millions of strange shadows on you tend? Since everyone hath, every one, one shade, And you, but one, can every shadow lend: Describe Adonis and the counterfeit Is poorly imitated after you, On Helen's cheek all art of beauty set, And you, in Grecian tires are painted new; Speak of the spring and foison of the year, The one doth shadow of your beauty show, The other as your bounty doth appear, And you in every blessed shape we know. In all external grace you have some part, But you, like none, none you for constant heart. |

|

What is your substance, whereof are you made

That millions of strange shadows on you tend? |

What is your substance, or essence, what are you made of, that it is possible that you have millions of wondrous, unfamiliar appearances?

We have repeatedly encountered 'shadow' to mean 'image' or even 'vision', such as in Sonnet 27, where "my soul's imaginary sight | Presents thy shadow to my sightless view," or in Sonnet 43: "Then thou, whose shadow shadows doth make bright." And 'strange' here does not so much imply our often negatively connotated meaning of 'alien', or 'weird' but simply 'unfamiliar' or, in this context, 'wondrous' or even 'awe-inspiring'. Fascinating is the phrasing 'on you tend': it suggests that these shadows, these images or appearances, are not you, but they serve you, and editors read different meanings into this that can quite readily become laboured; what it certainly does is elevate the young man to iconic status, capable of representing, and being represented in, all forms of beauty, as the sonnet goes on to explain. |

|

Since everyone hath, every one, one shade,

And you, but one, can every shadow lend. |

The above question is being asked, seeing that it is the case that every person has one appearance – and usually one appearance only – whereas you, who are only one person, can be seen in every appearance there is, though by implication this is every beautiful appearance there is.

The young man, in other words, with his beauty can 'lend' his appearance to every ideal of beauty. This is once again not an original idea, but one that appears frequently in poetry: that the beloved beauty encompasses, and therefore is seen, in every beauty there is. |

|

Describe Adonis, and the counterfeit

Is poorly imitated after you. |

If one were to describe Adonis – either in words or indeed by painting him – then this 'counterfeit' copy of him, which therefore can only ever be inadequate, turns out to be a poor imitation of you.

Adonis in Greek mythology is the mortal lover of the goddesses and gods Aphrodite, Persephone, Apollo, and Heracles, among others, who was and still is considered the archetype of male beauty. He was revered and celebrated and is therefore portrayed in innumerable statues and images from antiquity to the present day. The word 'counterfeit', meanwhile, although it has connotations of inadequacy and something not being a match to the original, does not necessarily mean a copy or representation that is made to deceive, as it would be interpreted today. We came across this also in Sonnet 16. |

|

On Helen's cheek all art of beauty set

And you, in Grecian tires, are painted new. |

Similarly, if we were to apply all he finest artistry there is to paint Helen of Troy, what we'd end up with is an image of you, in Greek attire.

Helen of Troy is "the face that launched a thousand ships," as Christopher Marlowe puts it in his play Doctor Faustus: she was believed or said at the time to have been the 'most beautiful woman on earth'. The fact that the young man appears as and in both the male ideal of beauty, Adonis, and the female ideal of beauty, Helen, is significant. In Sonnet 20, Shakespeare directly told the young man: A woman's face, with Nature's own hand painted Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion And this sonnet also strongly alludes to the androgynous beauty of the young lover, which again draws a connection between this sonnet, Sonnet 53 and a much earlier sonnet, Sonnet 20, suggesting a continuity or at the very least a strong connecting link, also in the person the poem is addressed to. |

|

Speak of the spring and foison of the year,

The one doth shadow of your beauty show, The other as your bounty doth appear, |

If we speak of spring or of the rich harvest of autumn, then all that happens is that the one, spring, conjures up an image of your beauty, while the other, autumn, is but a mere representation of your bounty, meaning your abundant riches and qualities.

Once or twice early on in the series, and certainly when discussing the famous Sonnet 18, Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day?, we noted how beautiful to the Elizabethan poet a spring or summer day really was. So without wanting to regurgitate this here, we may bear in mind just how cold, grey, dark, wet, drab, and deprived of visual stimuli your average English winter mostly was at the time... |

|

And you in every blessed shape we know.

|

And in the same way as described, you simply appear in everything that is good and beautiful and therefore blessed in the world.

|

|

In all external grace you have some part,

|

In everything that is outwardly graceful – and with this comes the connotation now also of nobility, valour, and value – you have some part on account of your beauty...

|

|

But you, like none, none you for constant heart.

|

And this is one of the trickiest and most complex lines in the entire collection so far, because it simply can mean two categorically different things. Either

a) quite flattering: ...but while you are represented in all external beauty, you are like nobody else when it comes to the constancy of your heart. In other words: yes, your 'outward fair', as I, the poet, called it in Sonnet 16, shines in every thing that is beautiful, but your 'inward worth' is yours alone and it is unparalleled and unmatched. This, in view of what happened in Sonnets 33 to 35 and 40 to 43 may be considered wishful thinking. Or b) rather less flattering: ...but you, who are like nobody else, are nobody's constant heart, meaning effectively, yes, you are unimaginably beautiful and I see you in everything I look at or speak about or think of, but you are not constant and faithful in your affections. This would seem closer to the 'truth' as far as we can understand it from what we have learnt so far about the young man. If, as we may continue to assume, the young man is indeed an aristocrat of considerable power and social standing then Shakespeare resorting to such exquisitely ambiguous double layering of his pronouncement makes perfect sense, of course: you do not want to directly insult a young lord whom you may already be indebted to for patronage or whose patronage you seek, quite apart from being his lover. And even if we were to assume that the young man is of little social significance in his world, this still makes for a stupendously skilful way of speaking a truth that someone may find hard to hear. |

The tender and complex Sonnet 53 – just over a third into the series – finds yet another entirely new register and conjures up not only an image of a beautiful person being admired, but also a sense of great intimacy that comes delicately paired with that feeling of wonder at something almost alien that may just be too good to be true.

The poem makes no reference to time of day or location, yet I can't help but imagine this as the blissful hour of waking up next to your most beautiful lover and musing over their gorgeousness. This – I hasten to emphasise – is therefore pure conjecture. What the words themselves do tell us are essentially three things:

First: By opening with a question, William Shakespeare immediately allows for myriad possible answers. Because this here is not a purely rhetorical question, as for example is the most famous of them all in Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day? This is an actual query which therefore stems from an actual curiosity. Which is telling.

Throughout our entire journey together so far we have been getting the impression – sometimes stronger, sometimes less so – that there is a basic inequivalence to both, these two people as individuals and to the way they relate to each other. It would go too far and also be possibly tedious to rehearse the many facets and aspects to this here allover again, but if Sonnet 53 now positions our poet as someone who looks upon his lover as quite different to him and wonders just what exactly this man is made of, then this rather fits our perception that William Shakespeare is in love with someone who is not only younger than he, not only exceptionally beautiful, but also quite out of his league. None, some, or any of this may or may not be consciously expressed here, and as on many previous occasions we need to bear in mind that comparing your lover to the iconic beauties of Greek mythology and indeed to any other marvellous thing under the sun is not original or new. In fact, in Sonnet 21, Shakespeare himself seemed to mock the kind of poet, "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse, | Who heaven itself for ornament doth use | And every fair with his fair doth rehearse."

But therein lies the point. Shakespeare does not set out with his comparisons to Helen, Adonis, autumn and spring, he sets out with the question, "What is your substance, whereof are you made?" And this immediately elevates the young man and idealises him: arguably it also dehumanises him, by turning him into the sum of all things beautiful, but principally it puts a distance between the poet and his young lover that amounts to, or at the very least allows for, the question: are you real? And for this also read: are you true?

Second, and we already briefly touched on this: With its paired comparison to both Adonis and Helen, the male and female ideals of beauty respectively, the sonnet draws a direct link to Sonnet 20. This is extraordinarily significant, because it is quite specific. There is an active school of thought which strongly advocates moving away from seeing these sonnets as being in any way biographical, let alone coherent, and which discourages reading into them any kind of continuity; and we will be talking about this approach in some detail very soon. But here we have a sonnet that makes a highly unusual gesture, by telling a young man that he is effectively the blueprint for both the classical ideal of male and the classical ideal of female beauty. This is not a universally applicable condition. Many young men would, certainly at the time, but also still today, be taken aback by being told that if you paint a picture of Helen of Troy, what comes out is in fact a portrait of them in Greek drag. The person whom Sonnet 20 is addressed to though seems to be both androgynous and happy to be seen so, and apparently the same applies to the person whom Sonnet 53 is addressed to.

Does this mean it is certain that Sonnet 53 is addressed to the same young man as Sonnet 20? Of course not, nothing is. Is it likely though? In light of what we know and have learnt so far, absolutely it is. And here now I am happy to remind ourselves that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And this would mean that the arc of these sonnets spans from Sonnet 20 through Sonnet 53, because at no point so far have we had good reason to believe that we are talking to or about anyone else, except where the mistress came into play in addition to the young man and turned the relationship all of a sudden surprisingly post-modern. And since we detected no clear or obvious sign of a break between the Procreation Sonnets 1-17 and the sonnets that immediately follow, Sonnets 18, 19, and 20 – in fact the opposite, we detected strong indications that we are talking to and about the same person – we would appear to have a broadly continuous arc spanning all the way from Sonnet 1 to Sonnet 53.

Third. No matter how sure we can be that this young man is astonishingly beautiful, and bearing in mind gladly that beauty is in the eye of the beholder we can also rephrase this slightly and say, no matter how sure William Shakespeare can be that to him this young man is astonishingly beautiful – and that to him he is, of this we really need not be querisome – Shakespeare, and therefore we, cannot be sure of his constancy. His faithfulness. This sonnet manages in a singularly ambiguous way to either compliment the young man and tell him he is unparalleled in his constant heart, or to tell him that lovely though he is, he will probably never be faithful. This is extraordinary. It is extraordinarily skilled sonneteering to start with, and it is also extraordinary for a poet in Shakespeare's position to put this in words so convolutedly clearly. There is a particular art in saying things in words that can be understood by different people differently, and Shakespeare has obviously mastered it, because this is hardly a mistake. I've said it before, I will say it again: Shakespeare can express himself with absolute direct simplicity when he feels like it, so when he elects to be ambiguous and multi-layered, we can quite safely assume there is a reason for this. What exactly the reason is, we don't know, but some fairly obvious possible ones present themselves:

- If, as the mention by Francis Meres in 1598 of some "sugar'd sonnets" as circulating among Shakespeare's "private friends" suggests, at least some people knew about the existence of these sonnets at or near their time of writing, then Shakespeare himself must have been aware that what to him may well have been entirely private poems could find their way out into the more or less pubic domain, and that would impose on him a duty of care towards the object of his affections. The fact alone that he never mentions anyone by anything close to a name also attests to this. And so if you want to communicate to your lover that you deem him perfect, but oh how you wish he were faithful to you, then doing so with a sonnet, which after all stands in the tradition of a love poem, that to all intents and purposes seems to relate how uniquely constant he is, is one clever way of going about it.

– If, as we have been getting the impression, the character we are dealing with is both, powerful and fickle, and will not be told what to do by anyone, then an indirect approach of half compliment, half reprimand may not be such a bad idea either. It may of course backfire: you may end up insulting the lover after all and thus gain nothing by it, but at least, in view of the above, you haven't slandered or let alone libel him.

– The person in question may have something of a reputation. And if you are on really excellent terms with each other and your small group of 'private friends' has some insight into your relationship, then ironically praising his constancy in a way that everyone in the room would understand to really be pulling him up on his philandering would amount to a humorous, charming, lighthearted way of dealing with what still, and all of this notwithstanding, may for Shakespeare be quite a painful set of circumstances.

And this latter point is one we shouldn't entirely lose sight of and it is one which I haven't really properly made much before: both William Shakespeare and his young lover, whoever he is, are part of a society. And they are both visible: Shakespeare as a poet and increasingly successful playwright and actor, the young man as a member of the aristocracy, possibly, as we have seen, very close to the seat of power. The play of Shakespeare's that most uses and toys with the sonnet as a poetic form is Love's Labours Lost. First published in 1598, the same year as Mere's first mention of Shakespeare's sonnets, it follows a king and three young noblemen who swear an oath that they will eschew the company of women for three years to concentrate on their studies. No sooner have they settled on this, than a princess with her three ladies appears on the scene and naturally everybody falls in love. It's a funny, sophisticated, in parts perhaps a little and also quite deliberately pretentious comedy that features characters the audience at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, where it was first performed, would have easily recognised and relished witnessing as they woo and deceive each other, often with elaborate verbosity. It's the play that contains Shakespeare's longest scene, one of his longest speeches, and his longest word, though not coined by him: honorificabilitudinitatibus, 'the state of being able to achieve honours'.

Theirs was a culture of words and wit, of showing off and of competing with each other over who can be most dextrous with language. One of the most important things that sets Shakespeare's sonnets apart as a body of work is their heartfelt sincerity, their incredible scope of topics, their great emotional range. But that does not mean that they cannot contain and celebrate a lightness of touch, a wittiness, a tease.

And so maybe that is in fact what Sonnet 53 at least in parts is: a tease to the lover and friend, to the adorable boy who looks a bit like a girl who often perhaps behaves like a petulant child when by now he is either already, or about to become one of the richest grownups in England, acceding to a title and an inheritance that in today's money is worth billions. And even if the young man is not the person to whom these particular specifics apply, it still sounds like just the kind of sonnet you would write to someone whom you are in a good place with right here and right now, whom you adore and find beyond measure beautiful, but of whom you just wish they could be yours alone, and you know they know that that is what you mean, and maybe you can even both have a bit of a laugh about it.

How much of a laughing matter it is for Shakespeare though is open to doubt. the next poem in the series, Sonnet 54 extols the virtue of 'truth', as in truthfulness, Sonnet 55 revisits the idea of the sonnet as a lasting memorial to the young man, and Sonnet 56 enters a plea with love itself directly to renew itself and not to let a period of separation spell the end, before with Sonnets 57 & 58 we reach another plateau of yet another kind. And what all these sonnets, different as they are from each other, have in common is that they show us a poet who struggles with this precise question: how much can I call my lover really mine? Not, then, as with this sonnet, what is your essence? But what, essentially, are you to me and what, therefore, am I to you?

The poem makes no reference to time of day or location, yet I can't help but imagine this as the blissful hour of waking up next to your most beautiful lover and musing over their gorgeousness. This – I hasten to emphasise – is therefore pure conjecture. What the words themselves do tell us are essentially three things:

First: By opening with a question, William Shakespeare immediately allows for myriad possible answers. Because this here is not a purely rhetorical question, as for example is the most famous of them all in Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day? This is an actual query which therefore stems from an actual curiosity. Which is telling.

Throughout our entire journey together so far we have been getting the impression – sometimes stronger, sometimes less so – that there is a basic inequivalence to both, these two people as individuals and to the way they relate to each other. It would go too far and also be possibly tedious to rehearse the many facets and aspects to this here allover again, but if Sonnet 53 now positions our poet as someone who looks upon his lover as quite different to him and wonders just what exactly this man is made of, then this rather fits our perception that William Shakespeare is in love with someone who is not only younger than he, not only exceptionally beautiful, but also quite out of his league. None, some, or any of this may or may not be consciously expressed here, and as on many previous occasions we need to bear in mind that comparing your lover to the iconic beauties of Greek mythology and indeed to any other marvellous thing under the sun is not original or new. In fact, in Sonnet 21, Shakespeare himself seemed to mock the kind of poet, "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse, | Who heaven itself for ornament doth use | And every fair with his fair doth rehearse."

But therein lies the point. Shakespeare does not set out with his comparisons to Helen, Adonis, autumn and spring, he sets out with the question, "What is your substance, whereof are you made?" And this immediately elevates the young man and idealises him: arguably it also dehumanises him, by turning him into the sum of all things beautiful, but principally it puts a distance between the poet and his young lover that amounts to, or at the very least allows for, the question: are you real? And for this also read: are you true?

Second, and we already briefly touched on this: With its paired comparison to both Adonis and Helen, the male and female ideals of beauty respectively, the sonnet draws a direct link to Sonnet 20. This is extraordinarily significant, because it is quite specific. There is an active school of thought which strongly advocates moving away from seeing these sonnets as being in any way biographical, let alone coherent, and which discourages reading into them any kind of continuity; and we will be talking about this approach in some detail very soon. But here we have a sonnet that makes a highly unusual gesture, by telling a young man that he is effectively the blueprint for both the classical ideal of male and the classical ideal of female beauty. This is not a universally applicable condition. Many young men would, certainly at the time, but also still today, be taken aback by being told that if you paint a picture of Helen of Troy, what comes out is in fact a portrait of them in Greek drag. The person whom Sonnet 20 is addressed to though seems to be both androgynous and happy to be seen so, and apparently the same applies to the person whom Sonnet 53 is addressed to.

Does this mean it is certain that Sonnet 53 is addressed to the same young man as Sonnet 20? Of course not, nothing is. Is it likely though? In light of what we know and have learnt so far, absolutely it is. And here now I am happy to remind ourselves that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And this would mean that the arc of these sonnets spans from Sonnet 20 through Sonnet 53, because at no point so far have we had good reason to believe that we are talking to or about anyone else, except where the mistress came into play in addition to the young man and turned the relationship all of a sudden surprisingly post-modern. And since we detected no clear or obvious sign of a break between the Procreation Sonnets 1-17 and the sonnets that immediately follow, Sonnets 18, 19, and 20 – in fact the opposite, we detected strong indications that we are talking to and about the same person – we would appear to have a broadly continuous arc spanning all the way from Sonnet 1 to Sonnet 53.

Third. No matter how sure we can be that this young man is astonishingly beautiful, and bearing in mind gladly that beauty is in the eye of the beholder we can also rephrase this slightly and say, no matter how sure William Shakespeare can be that to him this young man is astonishingly beautiful – and that to him he is, of this we really need not be querisome – Shakespeare, and therefore we, cannot be sure of his constancy. His faithfulness. This sonnet manages in a singularly ambiguous way to either compliment the young man and tell him he is unparalleled in his constant heart, or to tell him that lovely though he is, he will probably never be faithful. This is extraordinary. It is extraordinarily skilled sonneteering to start with, and it is also extraordinary for a poet in Shakespeare's position to put this in words so convolutedly clearly. There is a particular art in saying things in words that can be understood by different people differently, and Shakespeare has obviously mastered it, because this is hardly a mistake. I've said it before, I will say it again: Shakespeare can express himself with absolute direct simplicity when he feels like it, so when he elects to be ambiguous and multi-layered, we can quite safely assume there is a reason for this. What exactly the reason is, we don't know, but some fairly obvious possible ones present themselves:

- If, as the mention by Francis Meres in 1598 of some "sugar'd sonnets" as circulating among Shakespeare's "private friends" suggests, at least some people knew about the existence of these sonnets at or near their time of writing, then Shakespeare himself must have been aware that what to him may well have been entirely private poems could find their way out into the more or less pubic domain, and that would impose on him a duty of care towards the object of his affections. The fact alone that he never mentions anyone by anything close to a name also attests to this. And so if you want to communicate to your lover that you deem him perfect, but oh how you wish he were faithful to you, then doing so with a sonnet, which after all stands in the tradition of a love poem, that to all intents and purposes seems to relate how uniquely constant he is, is one clever way of going about it.

– If, as we have been getting the impression, the character we are dealing with is both, powerful and fickle, and will not be told what to do by anyone, then an indirect approach of half compliment, half reprimand may not be such a bad idea either. It may of course backfire: you may end up insulting the lover after all and thus gain nothing by it, but at least, in view of the above, you haven't slandered or let alone libel him.

– The person in question may have something of a reputation. And if you are on really excellent terms with each other and your small group of 'private friends' has some insight into your relationship, then ironically praising his constancy in a way that everyone in the room would understand to really be pulling him up on his philandering would amount to a humorous, charming, lighthearted way of dealing with what still, and all of this notwithstanding, may for Shakespeare be quite a painful set of circumstances.

And this latter point is one we shouldn't entirely lose sight of and it is one which I haven't really properly made much before: both William Shakespeare and his young lover, whoever he is, are part of a society. And they are both visible: Shakespeare as a poet and increasingly successful playwright and actor, the young man as a member of the aristocracy, possibly, as we have seen, very close to the seat of power. The play of Shakespeare's that most uses and toys with the sonnet as a poetic form is Love's Labours Lost. First published in 1598, the same year as Mere's first mention of Shakespeare's sonnets, it follows a king and three young noblemen who swear an oath that they will eschew the company of women for three years to concentrate on their studies. No sooner have they settled on this, than a princess with her three ladies appears on the scene and naturally everybody falls in love. It's a funny, sophisticated, in parts perhaps a little and also quite deliberately pretentious comedy that features characters the audience at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, where it was first performed, would have easily recognised and relished witnessing as they woo and deceive each other, often with elaborate verbosity. It's the play that contains Shakespeare's longest scene, one of his longest speeches, and his longest word, though not coined by him: honorificabilitudinitatibus, 'the state of being able to achieve honours'.

Theirs was a culture of words and wit, of showing off and of competing with each other over who can be most dextrous with language. One of the most important things that sets Shakespeare's sonnets apart as a body of work is their heartfelt sincerity, their incredible scope of topics, their great emotional range. But that does not mean that they cannot contain and celebrate a lightness of touch, a wittiness, a tease.

And so maybe that is in fact what Sonnet 53 at least in parts is: a tease to the lover and friend, to the adorable boy who looks a bit like a girl who often perhaps behaves like a petulant child when by now he is either already, or about to become one of the richest grownups in England, acceding to a title and an inheritance that in today's money is worth billions. And even if the young man is not the person to whom these particular specifics apply, it still sounds like just the kind of sonnet you would write to someone whom you are in a good place with right here and right now, whom you adore and find beyond measure beautiful, but of whom you just wish they could be yours alone, and you know they know that that is what you mean, and maybe you can even both have a bit of a laugh about it.

How much of a laughing matter it is for Shakespeare though is open to doubt. the next poem in the series, Sonnet 54 extols the virtue of 'truth', as in truthfulness, Sonnet 55 revisits the idea of the sonnet as a lasting memorial to the young man, and Sonnet 56 enters a plea with love itself directly to renew itself and not to let a period of separation spell the end, before with Sonnets 57 & 58 we reach another plateau of yet another kind. And what all these sonnets, different as they are from each other, have in common is that they show us a poet who struggles with this precise question: how much can I call my lover really mine? Not, then, as with this sonnet, what is your essence? But what, essentially, are you to me and what, therefore, am I to you?

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!