Sonnet 31: Thy Bosom Is Endeared With All Hearts

|

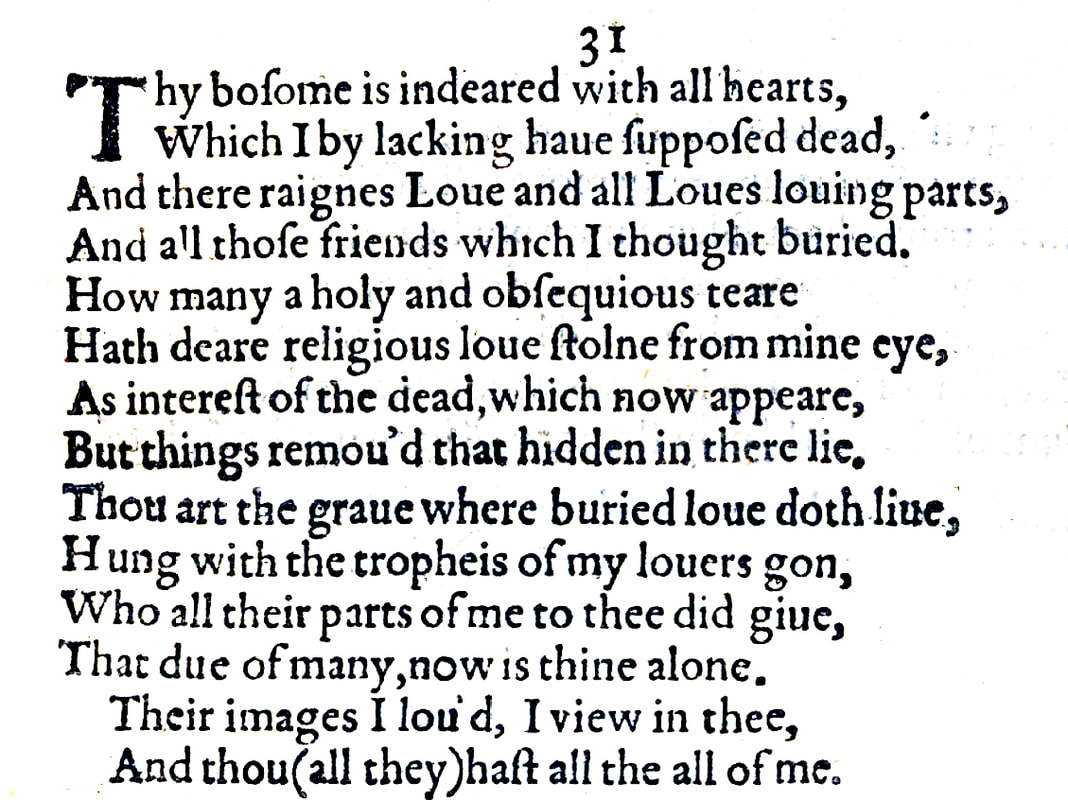

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I by lacking have supposed dead, And there reigns love and all love's loving parts, And all those friends which I thought buried. How many a holy and obsequious tear Hath dear religious love stolen from mine eye As interest of the dead, which now appear But things removed that hidden in thee lie: Thou art the grave where buried love doth live, Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone, Who all their parts of me to thee did give, That due of many now is thine alone. Their images I loved I view in thee, And thou, all they, hast all the all of me. |

|

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I, by lacking, have supposed dead, |

Your heart is enriched, or made precious, by all those hearts of which I thought they were dead, because I lack them, meaning they are absent from me now.

'Bosom', much as 'breast' is often used as synonymous with 'heart', while 'endeared' – here pronounced with three syllables – can also mean 'loved' or, as we would use it today, 'made lovable', as in: 'he endeared himself to me with his charm'. The multi-layering is, of course, typical of Shakespeare who here manages to convey in one word both a sense of the young man himself being of great worth and also being loved and worthy of love and being made even more precious by containing the lovers whom I thought dead. The line also appears to reference the previous sonnet directly, in which Shakespeare said: Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow, For precious friends hid in death's dateless night Here now, either these same friends, or some other hearts and therefore people whom I have loved, turn out to be not dead at all but continue to live in the young man: |

|

And there reigns love, and all love's loving parts,

And all those friends which I thought buried. |

Because there, in your heart, love reigns. And it does so with all love's loving parts.

We don't know what exactly Shakespeare may have in mind when he talks about 'all love's loving parts', but what offers itself readily is of course the body parts that are involved in love and 'love making'. The repetition of the word 'love' hints strongly at word play here and the luscious alliteration it provides enforces this sensual-sexual innuendo. But not only does love in every which way we can think of reign in your heart, which is also your breast, which is also your bosom, which is also therefore, your body, but all those friends whom I considered to be dead are present and reign there too through love. We noted in the previous sonnet how 'Dear Friend' there really – as it addresses the young man directly – needs to be read with a romantic connotation, and this sonnet moves us further in this direction where the 'friends which I thought buried' are increasingly clearly to be considered lovers. Note that 'buried' is pronounced with three syllables here: burièd. |

|

How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stolen from mine eye |

How many tears have I shed in a pure, sanctified, even indeed sacred love.

The contrast to the 'love and all love's loving parts' is stark: the love here referred to is 'dear' and 'religious', meaning of course it is spiritual, emotional, but not sexual. And these 'holy' tears are also 'obsequious', meaning they are devotional, both in the sense of religious prayer, such as spoken or heard during a funeral ceremony, and also perhaps in the sense of a devotion to the friends who have died. The word 'obsequious' does not, in Shakespeare's day, have the negative connotations it carries today of 'servile' or 'obsessively attentive', but goes hand-in-hand with 'holy' to mean sincere and exalted. Also, 'obsequious' should really be pronounced with three syllables here, and 'stolen' as one syllable: stol'n. |

|

As interest of the dead, which now appear

But things removed that hidden in thee lie. |

These tears that I have shed for loved ones who have died are like interest one pays on the grief or sorrow that one owes to the dead. But as it turns out, I need not have taken out this debt of sorrow, and therefore paid the interest in tears, because these dead friends for whom I have prayed and cried, they are all to be found hidden in you.

The Quarto Edition here has 'in there lie', but it is hard to resist the temptation to emend this to 'in thee', and many editors do so. 'There' and 'thee' often get confused by typesetters of the day and there are many instances where clearly one is mistaken for the other, but here the line does make sense as it is: you, the young man, are the grave where buried loves live, and these friends whom I had thought dead lie hidden in there, in that grave. But of course, since you are that 'grave', the line equally makes sense – and means almost exactly the same thing – if we change it to 'that hidden in thee lie'. What favours the emendation is that with it we get a gratifying emphasis on thee when reading the line out loud, and it also then leads directly into the 'Thou' of the next line, and so while I tend to err on the side of caution when changing the words of William Shakespeare, the rhythm of the line really does improve greatly by doing so, and seeing just how common the emendation is, I have – almost reluctantly – adopted it here. |

|

Thou art the grave where buried love doth live

|

You yourself are the place where the love that appears to have died actually lives.

It is a powerful image this: now the young man in his entirety is referred to as a grave where love does the opposite of what we would expect any thing or any one to do in a grave: it does not rest there in peace, it is alive and, to all intents and purposes, we get the impression, kicking! And it is worth pointing out here that the kind of grave we should imagine is not a pit in the earth: this is a vault or a chapel-like memorial of the kind we still see in some cemeteries as family graves, for example, similar perhaps to the place where Juliet lies buried for Romeo to find her: it is a walk-in space of some considerable size. |

|

Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone

|

And in this vault-like grave hang the emblems of my deceased lovers. An ancient grave of the type imagined here would often be decorated with the coat of arms or other symbols and valuable artefacts that represent the life and achievements of the deceased, so the idea that a grave could have trophies in it is not in itself unusual.

But two things of great note happen in this one line: firstly, the friends referred to above are now here called 'lovers', confirming what we believed we already knew, that we are really talking about friends with considerable benefits. Secondly, and directly tied into this, the language here becomes almost overtly sexual. 'Hung' then as now can refer to male genitalia, and trophies are what one obtains from conquests, and in the context of lovers these are clearly conquests of love. |

|

Who all their parts of me to thee did give,

That due of many now is thine alone. |

These lovers – by now residing in you – have given their share or title that they hold in me to you, meaning their 'right' or 'entitlement' to receive my love has now passed on to you.

It is entirely possible, though not certain, that 'parts' here too is a deliberate pun and placed to remind us of the fact that these are lovers with whom I have had sexual relations. And it would also make sense, it would underline the idea that William Shakespeare is here effectively saying to the young man: you are now the person whom I want to be sexually exclusive to. And if that is the case, then that makes this a very revealing sonnet indeed. |

|

Their images I loved I view in thee,

And thou, all they, hast all the all of me. |

In you I see the images of my lovers, and you, who now embody all of them, have all of me.

And with this, Shakespeare appears to put the lid on the matter and a seal on the relationship with the young man, by saying: I don't need these lovers of the past anymore, you are now my one and only. |

With the astonishingly bold, borderline brazen, Sonnet 31, William Shakespeare strikes a completely new tone and tells both his young lover and us things he has not revealed before. It comes as close as we have seen thus far to declaring a physical component to their relationship, and in doing so opens an entirely new chapter with a whole different dynamic.

Although Sonnet 31 does not directly spell out a sexual dimension, its tone, its immediacy, its multiple innuendo-laden references are in such stark contrast to the previous few sonnets, that we can be all but certain that something has shifted substantially. This immediately of course raises the question once again: can we be certain – if this sonnet is so different in tone and content – that it is addressed to the same young man, that it is in the right place in the sequence, even?

This is a comparatively easy question to answer. Always with the caveat that we know nothing for absolutely certain, the sonnet does make a direct reference to Sonnet 30, where I, the poet, explained that in my sessions of 'sweet silent thought' I may 'drown an eye' for precious friends who have died. Here, in Sonnet 31 I pick up on this and relate how I have cried for friends whom I had thought dead but who turn out to be alive and well, living in the heart of my lover.

There is an interesting contraction here, as it happens, because in Sonnet 30 Shakespeare said of his eye that it was 'unused to flow', which we thought implied that he is presenting himself as someone who rarely cries over matters, whereas here he is referring to the 'many tears' he has shed. But as contradictions go, this is less troubling than it seems. If you lose a good friend, then in the direct aftermath and at their funeral you may well shed many a tear, even if in general, as you go through your daily life, you are not one who often and readily cries.

What the sonnet also does not tell us but nevertheless appears to imply is that Shakespeare has returned from his travels. Assuming for the time-being – and as hitherto we have, mainly because we have found no good reason not to – that these sonnets so far form a chronological sequence, then we have seen Shakespeare send a 'written ambassage' with Sonnet 26 which was either dispatched from his journey or immediately beforehand.

With Sonnets 27 and 28 I unmistakably talked of the weariness my travels induced in me and how much I missed my young lover. Sonnet 29 related in a joyous manner how even when the whole world seems against me, simply remembering the friend's love makes my spirits soar, and in Sonnet 30 I expanded on this and conveyed how thinking of him restores to me the things I feel I have lost and ends the sorrows I have experienced.

Both Sonnet 29 and Sonnet 30 do not explicitly speak of a geographical absence, but their tone and atmosphere is very much still that of a man who is away from his lover, and nothing in them points to a reunion.

Sonnet 31 changes all that. It comes along with the exuberance and power of a man who is returned from his imposed absence and who not only finds that his love is waiting for him but also that whatever wobbles troubled him just as he departed have been allayed and the lover has said or done something to prompt this abundant relishing of, and giving over to, him.

What this sonnet sounds like is that I, William Shakespeare, have been welcomed back with open arms, and the fact that it is just at this point here that the language becomes almost overtly sexual is hard to put down to coincidence. Does this prove that William Shakespeare and the young man have now moved their relationship onto a sexual footing? It does not. We don't even know whether the young man ever receives this sonnet. We may still find ourselves entirely in Shakespeare's head; but whatever the reason, William Shakespeare here is saying to his young lover: you embody all my previous lovers. And he uses the word 'lovers'. This is not what one might reasonably think of as ambiguous or cautious or bashful language. Combine that with the vocabulary that goes along with it and you have, if not evidence, then scarcely subtle hinting of the kind that surely has to be rooted in something. If not in experience, then in fantasy, if not in fantasy, then in serious wishful thinking, if not that, then surely in lived experience: I am saying to you that in you reigns love and all love's loving parts. In you, buried love lives, and it is hung with the trophies of my lovers gone. You are all my former lovers rolled into one and you have all the all of me.

These lines were written at a time when it was absolutely not unusual for men to have any type of sexual relationship with other men, be it sincerely felt, transactional, opportunist, or tender loving and romantic, but when as a man you could be put to death for being found to have had sexual relations with another man. And so what these lines express is truly remarkable. Because they really and signally up the ante: they frame what has beyond doubt been established as a deeply felt connection, longing and sense of belonging, in a context of physical passion.

And there is one additional layer to Sonnet 31 that bears bringing to mind: we have, in Sonnet 30, accepted as real and entirely plausible that Shakespeare at his age now, which we know must be between 30 and 40, has had to suffer the loss of precious friends through untimely death. We also need not doubt that the terms 'friends' and 'lovers' in these poems are used interchangeably, and we touched on the reasons why. With this poem now though, Sonnet 31, a new possibility presents itself to not necessarily substitute but to supplement this literal meaning of deceased friends. That of 'buried love' not as referring to friends and lovers who have actually died, but who have died to me as friends and lovers because they went away, because they were short-lived affairs, or because the relationship for one or several of many million possible reasons ended, died. In other words: what this sonnet may well be doing is celebrate the revival of love, and quite specifically and almost explicitly physical love, which has been 'supposed dead'. A reawakening. And what could be more normal, more obvious, in a way, than just that.

Imagine yourself a struggling poet and budding playwright. You are in London, still relatively newly arrived. You have a wife and children back in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is the small market town in rural England where you grew up, where everybody knows everybody, and where you left soon after you got married. You then 'disappeared' for a while, but of course you didn't stop living. Or loving. You may well have had some adventures of the heart, of the mind, and indeed of the body. But this is Elizabethan England. There are no hookup apps, and although same sex relations in certain circles are fairly common, they are by many frowned upon to the point of being actively persecuted and punished. And the punishment could be cruel and severe. You meet this lovely, beautiful young man and fall head over heels in love with him. You do not hold back telling him. You overstep the mark maybe a bit with your words and your presumption and you get put in your place a bit, accordingly. You then get called away, and you miss this man whom you still may have not more than loved and dreamed about. You come back to London and he is there for you. You are together, you are close. You're alive and you love. Maybe, quite possibly, for the first time in ages.

It really doesn't matter what the details are, how physical, how sexual, how intense this coming together is. What we get from this sonnet is that something has changed and what has changed is as much reflected in the words themselves as it can be. And as if to confirm that things really are different to they way they were before, the next sonnet, Sonnet 32, strikes a completely different tone again. Also quite cocky, but in a much subtler way, and it does so just before something happens that could cast doubt over the future of this relationship, while providing extraordinary clarity about just how far it has got by now...

Although Sonnet 31 does not directly spell out a sexual dimension, its tone, its immediacy, its multiple innuendo-laden references are in such stark contrast to the previous few sonnets, that we can be all but certain that something has shifted substantially. This immediately of course raises the question once again: can we be certain – if this sonnet is so different in tone and content – that it is addressed to the same young man, that it is in the right place in the sequence, even?

This is a comparatively easy question to answer. Always with the caveat that we know nothing for absolutely certain, the sonnet does make a direct reference to Sonnet 30, where I, the poet, explained that in my sessions of 'sweet silent thought' I may 'drown an eye' for precious friends who have died. Here, in Sonnet 31 I pick up on this and relate how I have cried for friends whom I had thought dead but who turn out to be alive and well, living in the heart of my lover.

There is an interesting contraction here, as it happens, because in Sonnet 30 Shakespeare said of his eye that it was 'unused to flow', which we thought implied that he is presenting himself as someone who rarely cries over matters, whereas here he is referring to the 'many tears' he has shed. But as contradictions go, this is less troubling than it seems. If you lose a good friend, then in the direct aftermath and at their funeral you may well shed many a tear, even if in general, as you go through your daily life, you are not one who often and readily cries.

What the sonnet also does not tell us but nevertheless appears to imply is that Shakespeare has returned from his travels. Assuming for the time-being – and as hitherto we have, mainly because we have found no good reason not to – that these sonnets so far form a chronological sequence, then we have seen Shakespeare send a 'written ambassage' with Sonnet 26 which was either dispatched from his journey or immediately beforehand.

With Sonnets 27 and 28 I unmistakably talked of the weariness my travels induced in me and how much I missed my young lover. Sonnet 29 related in a joyous manner how even when the whole world seems against me, simply remembering the friend's love makes my spirits soar, and in Sonnet 30 I expanded on this and conveyed how thinking of him restores to me the things I feel I have lost and ends the sorrows I have experienced.

Both Sonnet 29 and Sonnet 30 do not explicitly speak of a geographical absence, but their tone and atmosphere is very much still that of a man who is away from his lover, and nothing in them points to a reunion.

Sonnet 31 changes all that. It comes along with the exuberance and power of a man who is returned from his imposed absence and who not only finds that his love is waiting for him but also that whatever wobbles troubled him just as he departed have been allayed and the lover has said or done something to prompt this abundant relishing of, and giving over to, him.

What this sonnet sounds like is that I, William Shakespeare, have been welcomed back with open arms, and the fact that it is just at this point here that the language becomes almost overtly sexual is hard to put down to coincidence. Does this prove that William Shakespeare and the young man have now moved their relationship onto a sexual footing? It does not. We don't even know whether the young man ever receives this sonnet. We may still find ourselves entirely in Shakespeare's head; but whatever the reason, William Shakespeare here is saying to his young lover: you embody all my previous lovers. And he uses the word 'lovers'. This is not what one might reasonably think of as ambiguous or cautious or bashful language. Combine that with the vocabulary that goes along with it and you have, if not evidence, then scarcely subtle hinting of the kind that surely has to be rooted in something. If not in experience, then in fantasy, if not in fantasy, then in serious wishful thinking, if not that, then surely in lived experience: I am saying to you that in you reigns love and all love's loving parts. In you, buried love lives, and it is hung with the trophies of my lovers gone. You are all my former lovers rolled into one and you have all the all of me.

These lines were written at a time when it was absolutely not unusual for men to have any type of sexual relationship with other men, be it sincerely felt, transactional, opportunist, or tender loving and romantic, but when as a man you could be put to death for being found to have had sexual relations with another man. And so what these lines express is truly remarkable. Because they really and signally up the ante: they frame what has beyond doubt been established as a deeply felt connection, longing and sense of belonging, in a context of physical passion.

And there is one additional layer to Sonnet 31 that bears bringing to mind: we have, in Sonnet 30, accepted as real and entirely plausible that Shakespeare at his age now, which we know must be between 30 and 40, has had to suffer the loss of precious friends through untimely death. We also need not doubt that the terms 'friends' and 'lovers' in these poems are used interchangeably, and we touched on the reasons why. With this poem now though, Sonnet 31, a new possibility presents itself to not necessarily substitute but to supplement this literal meaning of deceased friends. That of 'buried love' not as referring to friends and lovers who have actually died, but who have died to me as friends and lovers because they went away, because they were short-lived affairs, or because the relationship for one or several of many million possible reasons ended, died. In other words: what this sonnet may well be doing is celebrate the revival of love, and quite specifically and almost explicitly physical love, which has been 'supposed dead'. A reawakening. And what could be more normal, more obvious, in a way, than just that.

Imagine yourself a struggling poet and budding playwright. You are in London, still relatively newly arrived. You have a wife and children back in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is the small market town in rural England where you grew up, where everybody knows everybody, and where you left soon after you got married. You then 'disappeared' for a while, but of course you didn't stop living. Or loving. You may well have had some adventures of the heart, of the mind, and indeed of the body. But this is Elizabethan England. There are no hookup apps, and although same sex relations in certain circles are fairly common, they are by many frowned upon to the point of being actively persecuted and punished. And the punishment could be cruel and severe. You meet this lovely, beautiful young man and fall head over heels in love with him. You do not hold back telling him. You overstep the mark maybe a bit with your words and your presumption and you get put in your place a bit, accordingly. You then get called away, and you miss this man whom you still may have not more than loved and dreamed about. You come back to London and he is there for you. You are together, you are close. You're alive and you love. Maybe, quite possibly, for the first time in ages.

It really doesn't matter what the details are, how physical, how sexual, how intense this coming together is. What we get from this sonnet is that something has changed and what has changed is as much reflected in the words themselves as it can be. And as if to confirm that things really are different to they way they were before, the next sonnet, Sonnet 32, strikes a completely different tone again. Also quite cocky, but in a much subtler way, and it does so just before something happens that could cast doubt over the future of this relationship, while providing extraordinary clarity about just how far it has got by now...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!