Sonnet 34: Why Didst Thou Promise Such a Beauteous Day

|

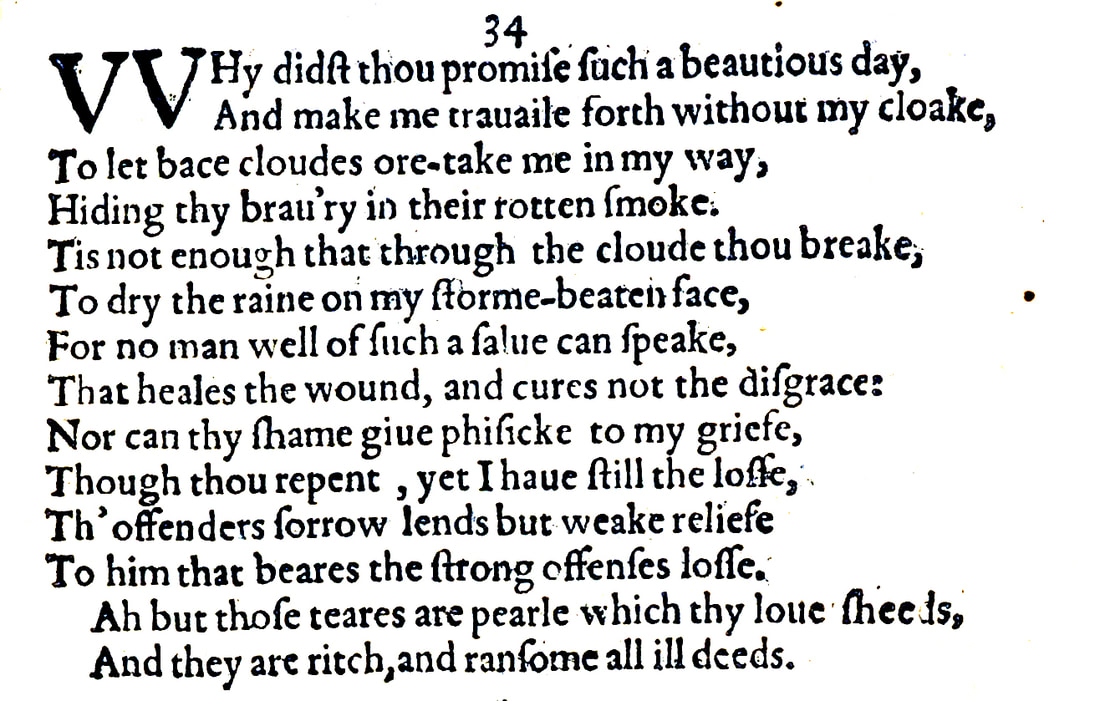

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day

And make me travel forth without my cloak, To let base clouds oretake me in my way, Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke? Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face, For no man well of such a salve can speak, That heals the wound and cures not the disgrace. Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief: Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss, Th'offender's sorrow lends but weak relief To him that bears the strong offence's cross. Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds. |

|

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day

And make me travel forth without my cloak |

Why did you promise me such a beautiful day and make me go outside without my coat or cloak?...

Both John Kerrigan in the Penguin edition of the Sonnets and Colin Burrow for Oxford point out that there is, or at any rate was, a proverb saying: 'although the sun shines, leave not your cloak at home'. Whether or not Shakespeare knew of this and is referencing it here, we cannot know for certain, but what the opening of this sonnet certainly asks the young man is: why did you promise me beautiful weather and make me bask in your sunshine when what happened next happened next: |

|

To let base clouds oretake me in my way,

|

...only to then let clouds gather and catch me out...

These 'base clouds' are surely the same as the 'basest clouds' of the previous Sonnet 33 which ride the celestial face, the sun: the bad metaphorical weather that is gathering here with these clouds is not only unpleasant, it is also vulgar, low, unworthy of the young man who is allowing this to happen. |

|

Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke?

|

...and these clouds hide your finery – your splendid appearance – in their toxic or noxious or wholly unwholesome vapours.

Shakespeare and his contemporaries didn't make any distinction between 'smoke', which strictly stems from something that is burning, and 'steam', which may emanate from all manner of heat-emitting sources, or even 'mist' and 'fog', or, as here, 'clouds'. The 'rotten' hints at a putrid smell that goes with it and so the accusation is a powerful one: you are debasing yourself by allowing your beauty, your grace, your honour, too – in fact your overall gorgeousness – to be enveloped by these stinking clouds. |

|

Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break

To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face, |

It is not enough that you now come running or galloping hither to dry my face which has been drenched by the rain you cast on me.

This suggests that the young man has apologised or is apologising for whatever it is he has done to cause this change of weather, but it is not enough: |

|

For no man well of such a salve can speak

That heals the wound and cures not the disgrace. |

Because nobody can speak well of the kind of remedy – a salve is really a soothing or restorative ointment – that only heals the wound but does nothing to cure the disgrace that has been commited.

Again, this links back directly to Sonnet 33 where the sun, masked from the world by base clouds, steals "unseen to west with his disgrace." And again the moral implications are certainly relevant: I, the poet, have been, or certainly feel I have been, dishonoured and you have disgraced yourself by your behaviour. |

|

Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief

|

Nor can the fact that you feel ashamed and – by implication – sorry for what you have done act as a healing agent or medicine to the grief you have caused me:

|

|

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss:

|

Although you repent your actions, I am still suffering the loss you have caused me.

The line does not spell out what that loss is, but it seems evident that the young man has gone and taken something from me, and it will soon become clear, in the following sonnets, just what exactly that was. |

|

Th'offender's sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offence's cross. |

The sorrow of the offending party – you – can only lend weak relief to him who has to suffer and bear the cross of that offence: me.

The Quarto Edition here repeats the word 'loss', but editors are pretty much in agreement across the board that this must be a mistake and that the only thing that makes sense in this biblical expression is 'cross'. |

|

Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds

|

Ah, but the tears that your love sheds – by implication tears of sorrow, regret, remorse – they are like pearls that I see running down your face.

|

|

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

|

And these pearls are of genuine, authentic high value and because of this they are able to atone for all the wrong you have done.

|

The devastated and devastatingly powerful Sonnet 34 picks up from where Sonnet 33 wanted to not only leave off but let go, and like a second wave of pain and mourning asks the young man directly why he has allowed the gorgeous sunshine of this relationship to be cast over with appalling weather. And unlike Sonnet 33, it not only tries, but apparently succeeds at forgiving the young man's conduct, paving the way for an even more conciliatory Sonnet 35, principally – and most tellingly – prompted by the young man's apparent response to being so called out.

When at the end of Sonnet 33 I felt inclined to liken what William Shakespeare was doing to the poetic equivalent a handbrake turn, then the closing couplet of this Sonnet offers a similarly radical change of direction, but there is a categorical difference, which – and this is just one of the reasons why this sonnet is so thrilling – gives us yet another entirely new insight. In Sonnet 33, I, the poet, William Shakespeare, reminded myself of the young man's status and simply acknowledged and accepted that if the sun in the sky will by necessity sometimes be stained by passing clouds, then so will every sun of the world, including the sun in my life, the young man. But here, what triggers the about-turn is the young man himself:

Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

It is almost as if we are in the moment there with Will and his young man as he admonishes the young man in this forceful manner, putting one layer on top of another, because not only have you done wrong, it is also not enough that after what you have done you now come running to apologise, because that does nothing to undo what you have done: look at me, I am the one who bears the cross of your transgression. And even as I speak, perhaps shout, I look at the young man with his beautiful, gentle face, his near-angelic expression, and I see tears of remorse running down his cheeks and I come to my senses and I want to hug him because I can't bear to see him suffer even though he made me suffer in the way he did first, and I either literally or just with my words wrap him into my arms and say: be done. Don't cry. It's all right. I forgive you.

The words "I do forgive" are not actually spoken here, but they will be soon. The sentiment though is already absolutely clear, as is the situation, and this may well be the sonnet that most palpably shows us the emerging dramatist at work: this could be a scene. This could be a speech in a play. There are no stage directions, because we don't need them, and of course Shakespeare with some famous and famously delightful exceptions – I am thinking as you are if you know it of "exit, pursued by a bear" in A Winter's Tale – hardly writes them.

We can picture this confrontation here, but more than picture, we can sense it, feel it, live it. I claim, in the subtitle to this podcast that here the Sonnets of William Shakespeare are being recited, revealed, and relived, and this is one of these moments where you feel you are right there, is it not? It is the sonnets themselves that achieve this, it has next to nothing to do with me, your podcaster, it has everything to do with the immediacy, the honesty, the heartfelt presence of this poetry.

We still, with Sonnet 34, don't know what the young man has done, but if for any reason we had felt that Sonnet 33 wasn't quite clear, quite convincing enough, then any such doubts that may or may not have been able to cast any lingering shadows are blown away by this storm, this outpouring of anger, hurt, dejection. Here are twelve lines that say: how could you do this to me? And, no you can't just come and say "I'm sorry." And then these two redeeming, absolving, caressing lines that say: I cannot be angry with you: all is well or will be.

The torrent of this storm and its so sudden abatement leave us wanting more, we want to hear Will actually say the things that are contained unformulated in this couplet, and William Shakespeare, being the poet he is and being human, obliges. Not to please us – he may never have intended for us to read or recite, let alone to relive, these particular sonnets – but to soothe, to reassure, to restore his young man. Because, as he will say and spell out for him soon: we two must not be enemies, no matter what happens.

Sonnet 34 is the lynchpin that holds Sonnet 33 and Sonnet 35 in place, which turn around it on this 'bumpy road to love', to invoke yet another song lyric from a much more recent yesteryear, this time by the elegant Gershwins.

But could this sonnet, the one that precedes it, and the one that follows, could they all have been written by William Shakespeare as abstract exercises in writing, detached from any experience, removed from any emotion he himself actually felt, unconnected to any real life person he knew or cared about?

We have asked ourselves this question before and now, just having become so caught up, so involved, to immersed in this sonnet, may not be a bad moment to take a step back and ask again, in all seriousness: is that not what a writer of plays could also quite possibly be doing here? Practising his craft? Setting up hypothetical constellations between characters and putting them into imagined scenarios? Is that not a distinct possibility? It is a possibility. Since we remind ourselves of the question, we must remind ourselves of the fact: we have no proof that this isn't so. Is it likely though? Is – everything we have heard and seen so far and everything that we are about to become witness to, everything we know and also everything we don't know about Shakespeare considered – is it truly probable that this is not a man unlocking, as Wordsworth put it, his heart for us? I hardly need to tell you what my view and more than my view my sense and immensely strong impression is. To me, as a writer, as a man, as a human who has done some living, a good deal of loving and probably too much longing as well in my time, this is as likely as it can be to be a truth that is here being shared. And in the absence of certainty, I have postulated before and am prepared here to repeat and remind ourselves – in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend.

And, most fortunately for us – although it is probably not, in the traditional sense, fortuitous, but quite deliberate on the poet's part, more exhilarating 'evidence' – circumstantial though it may be – lies just around the corner...

When at the end of Sonnet 33 I felt inclined to liken what William Shakespeare was doing to the poetic equivalent a handbrake turn, then the closing couplet of this Sonnet offers a similarly radical change of direction, but there is a categorical difference, which – and this is just one of the reasons why this sonnet is so thrilling – gives us yet another entirely new insight. In Sonnet 33, I, the poet, William Shakespeare, reminded myself of the young man's status and simply acknowledged and accepted that if the sun in the sky will by necessity sometimes be stained by passing clouds, then so will every sun of the world, including the sun in my life, the young man. But here, what triggers the about-turn is the young man himself:

Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

It is almost as if we are in the moment there with Will and his young man as he admonishes the young man in this forceful manner, putting one layer on top of another, because not only have you done wrong, it is also not enough that after what you have done you now come running to apologise, because that does nothing to undo what you have done: look at me, I am the one who bears the cross of your transgression. And even as I speak, perhaps shout, I look at the young man with his beautiful, gentle face, his near-angelic expression, and I see tears of remorse running down his cheeks and I come to my senses and I want to hug him because I can't bear to see him suffer even though he made me suffer in the way he did first, and I either literally or just with my words wrap him into my arms and say: be done. Don't cry. It's all right. I forgive you.

The words "I do forgive" are not actually spoken here, but they will be soon. The sentiment though is already absolutely clear, as is the situation, and this may well be the sonnet that most palpably shows us the emerging dramatist at work: this could be a scene. This could be a speech in a play. There are no stage directions, because we don't need them, and of course Shakespeare with some famous and famously delightful exceptions – I am thinking as you are if you know it of "exit, pursued by a bear" in A Winter's Tale – hardly writes them.

We can picture this confrontation here, but more than picture, we can sense it, feel it, live it. I claim, in the subtitle to this podcast that here the Sonnets of William Shakespeare are being recited, revealed, and relived, and this is one of these moments where you feel you are right there, is it not? It is the sonnets themselves that achieve this, it has next to nothing to do with me, your podcaster, it has everything to do with the immediacy, the honesty, the heartfelt presence of this poetry.

We still, with Sonnet 34, don't know what the young man has done, but if for any reason we had felt that Sonnet 33 wasn't quite clear, quite convincing enough, then any such doubts that may or may not have been able to cast any lingering shadows are blown away by this storm, this outpouring of anger, hurt, dejection. Here are twelve lines that say: how could you do this to me? And, no you can't just come and say "I'm sorry." And then these two redeeming, absolving, caressing lines that say: I cannot be angry with you: all is well or will be.

The torrent of this storm and its so sudden abatement leave us wanting more, we want to hear Will actually say the things that are contained unformulated in this couplet, and William Shakespeare, being the poet he is and being human, obliges. Not to please us – he may never have intended for us to read or recite, let alone to relive, these particular sonnets – but to soothe, to reassure, to restore his young man. Because, as he will say and spell out for him soon: we two must not be enemies, no matter what happens.

Sonnet 34 is the lynchpin that holds Sonnet 33 and Sonnet 35 in place, which turn around it on this 'bumpy road to love', to invoke yet another song lyric from a much more recent yesteryear, this time by the elegant Gershwins.

But could this sonnet, the one that precedes it, and the one that follows, could they all have been written by William Shakespeare as abstract exercises in writing, detached from any experience, removed from any emotion he himself actually felt, unconnected to any real life person he knew or cared about?

We have asked ourselves this question before and now, just having become so caught up, so involved, to immersed in this sonnet, may not be a bad moment to take a step back and ask again, in all seriousness: is that not what a writer of plays could also quite possibly be doing here? Practising his craft? Setting up hypothetical constellations between characters and putting them into imagined scenarios? Is that not a distinct possibility? It is a possibility. Since we remind ourselves of the question, we must remind ourselves of the fact: we have no proof that this isn't so. Is it likely though? Is – everything we have heard and seen so far and everything that we are about to become witness to, everything we know and also everything we don't know about Shakespeare considered – is it truly probable that this is not a man unlocking, as Wordsworth put it, his heart for us? I hardly need to tell you what my view and more than my view my sense and immensely strong impression is. To me, as a writer, as a man, as a human who has done some living, a good deal of loving and probably too much longing as well in my time, this is as likely as it can be to be a truth that is here being shared. And in the absence of certainty, I have postulated before and am prepared here to repeat and remind ourselves – in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend.

And, most fortunately for us – although it is probably not, in the traditional sense, fortuitous, but quite deliberate on the poet's part, more exhilarating 'evidence' – circumstantial though it may be – lies just around the corner...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!