Sonnet 69: Those Parts of Thee That the World's Eye Doth View

|

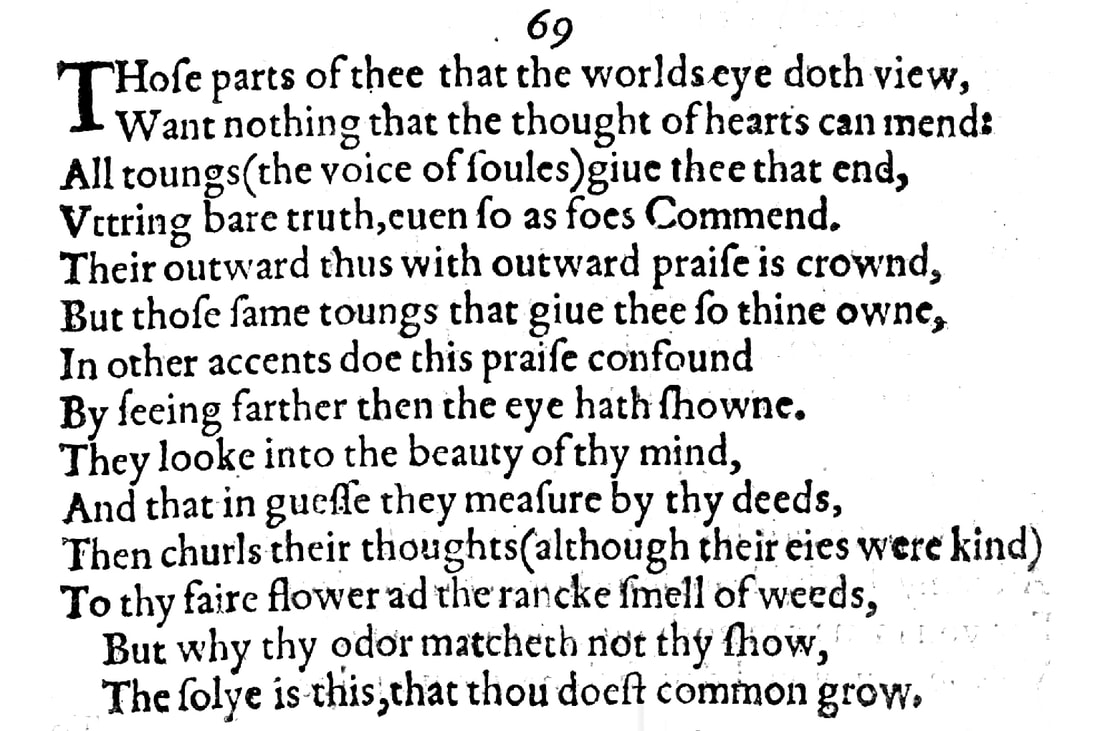

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend; All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due, Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend. Thy outward thus with outward praise is crowned, But those same tongues that give thee so thine own In other accents do this praise confound By seeing farther than the eye hath shown: They look into the beauty of thy mind, And that, in guess, they measure by thy deeds, Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind, To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds. But why thy odour matcheth not thy show, The soil is this: that thou dost common grow. |

|

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend; |

Those parts of you which are visible to the world – your outward appearance, your body, your face – have no imaginable shortcomings, they lack nothing one could think of: going by what people can see, you are perfect.

Occasionally in Shakespeare – and as we saw and noted in Sonnet 47 – we come across this association of thought with the heart, which stems from a conception at the time that thought was wholly or partly formed in the heart, rather than in the head, as we now know it is. |

|

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend. |

Everybody says so, and in saying so they are stating nothing but the bare truth, as even your enemies would agree.

The phrasing of this line, with its tongues that are further described as the voice of souls may be slightly idiosyncratic, but the meaning as we just saw is really very simple, but by using the word 'tongues' not just here but also a couple of lines later, Shakespeare does evoke the idea of 'wagging tongues', of gossip, even slanderous or scandalous in nature. The Quarto Edition often uses brackets, and in this instance, separating out 'the voice of souls' as it does is actually potentially clearer than the use of commas that is preferred by contemporary editors, including myself, as it makes it clear that 'the voice of souls' is simply a description of the 'tongues'. And we should also note that the Quarto Edition has 'give thee that end' here in line 3, but this is universally accepted as a typesetting error, since it doesn't rhyme with 'view', whereas 'give thee that due' does and it also makes perfect sense since we are familiar with the idea of giving someone their due. |

|

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crowned,

|

Your outward appearance thus is crowned with outward praise;

this hardly needs translating: everyone agrees you are beautiful and is happy to say so and compliment you accordingly. The Quarto Edition's 'Their' for 'Thy' here is also universally accepted to be a typesetting error. |

|

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own

In other accents do this praise confound |

But the same people who in this way give you what you deserve – namely praise for your outward appearance – use other words or a different kind of language to defeat, or undermine, this praise that they themselves have given you.

We've come across 'confound' on several occasions before: Sonnets 5, 8, 60, 63, 64, and 65 all use the verb along these or very similar lines. |

|

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown:

|

And they do so – they overthrow their own praise for you – by looking beyond your external appearance, beyond what is visible to the eye:

|

|

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that, in guess, they measure by thy deeds, |

They look into the beauty of your mind, and since they can't actually physically see your mind or its beauty, and are therefore kept guessing as to what it is like, they have to measure and assess it by your actions.

|

|

Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind,

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds. |

Then, having observed your actions, even though their eyes were kind and prompted them to heap praise upon you for your looks, their thoughts add to the beautiful flower that is your appearance the rank smell of weeds, for which read a bad reputation.

That weeds have a rank stench as opposed to the sweet smell of roses is a notion that appears elsewhere in Shakespeare, among others in Othello, and may be treated as a metaphorical or symbolic commonplace, even if 'weeds' do not all of them, obviously, exude an unpleasant fragrance. And a discussion takes place among editors as to who the 'churls' are in this line. You'll find it pointed out that the Quarto Edition – which is haphazard in its punctuation at any rate to say the least – does not sport any commas and this means that one could read the line either as saying, then these tongues, meaning these people, who are churls for doing what I am about to tell you, add the rank smell of weeds, or as, then some churls, namely these people's thoughts, do what I am about to tell you; so the thoughts become the churls. Either is plausible – it would not be the first time that Shakespeare gives thoughts a life and character of their own – and the two readings amount to almost the same thing. If we adopt the latter, and allow the thoughts to be churls, then that softens the line somewhat in relation to the people that are being talked about, and this may yet become of some significance when we get to Sonnet 70. |

|

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow. |

But the reason why this metaphorical bad smell that you are reputed to have does not match your beautiful appearance is that you yourself are growing common: you with your common – by implication perhaps even vulgar – behaviour are getting a foul reputation that stands in stark contrast to your immaculate appearance.

The soil is the ground in which both beautiful, sweet smelling roses as well as rank stinking weeds grow, and so calling this rational ground, the reason, 'soil' here is particularly dextrous writing, whereby it is worth pointing out that the Quarto Edition spells this word solye, which then as now is unusual, but editors appear to be pretty much of a mind that the way to render this is as 'soil', although there is potential for debate as to whether the primary meaning Shakespeare is going for here is soil as in 'earth' on the one hand or soil as in 'waste', 'sewage' on the other, or whether in fact he is punning on soil by deriving it from to assoil, which is an archaic term for 'to pardon', 'to acquit' or 'to clear' and may thus just about by extension be interpreted to also mean 'to explain' or 'to excuse'. |

Taken on its own, Sonnet 69 presents a devastating indictment of William Shakespeare's young lover. Its uncompromising juxtaposition of the young man's universally acknowledged beauty against his reputedly flawed character would be enough to put into question whether Shakespeare can still feel at all devoted to him: by itself, the poem is nothing short of shocking. But while it can absolutely stand on its own and nothing within it suggests that the point Shakespeare sets out to make has not been made and the argument he is pursuing not resolved by the end of it, it is then followed by Sonnet 70 which appears to directly pick up on the charges levied against the young man and equally forcefully defends him against any wrongdoing. The pair thus opens the widest and therefore most dynamic space of tension between two linked sonnets we have yet come across, and it poses further urgent questions about what is happening in the lives of William Shakespeare and his lover, and in their relationship.

Once again, and as on previous occasions, we will be looking at the two sonnets together, much as they demand, in the next episode, while concentrating on Sonnet 69 for just now.

By some margin the most eye-catching moment in this poem comes at the very end with the closing couplet:

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

Why is this so outrageous? Because in this couple of lines Shakespeare is telling the young man that in the eyes of the world he is 'growing common'. That in itself would be fairly remarkable, but he does not make any attempt, it seems, to really soften that blow. The only indication in this poem that he may not entirely agree with this assessment of the young man's conduct by a censorious world comes in the preantepenultimate line where he calls either the people denigrating the young man's reputation churls, or their thoughts. But 'churl' is not a very serious term. Its meaning is either 'peasant' or 'miser'. In Sonnet 1, he calls the young man himself a "tender churl" for holding on to his own procreation potential; in Sonnet 32 he speaks of a time "When that churl Death my bones in dust shall cover," and even Juliet, upon finding that her Romeo has killed himself with poison calls him a 'churl' for having left no drop for her to do likewise. And here in Sonnet 69, beyond this mild, in certain circumstances even tender, term of admonishment, he does not coach his language in any way to make it clear that this is just what the world thinks and not something he agrees with. In fact the opposite. The way this is phrased the sonnets states as well nigh categorically that this is the real, so as not to say obvious, reason why his reputation reeks.

But such an accusation – even if it is cited or repeated from other sources – becomes even more extraordinary once we consider who the likely recipient is of these lines. The sonnet of course doesn't tell us, and we are in no position yet to make any firm pronouncements on the identity of this young man, nor are we ever likely to get any solid, irrefutable, material evidence that will confirm once and for all whom we are dealing with. But what we can say with a by now appreciable level of confidence is that we are looking at a young nobleman.

We have, throughout this podcast so far, found clues dotted around these sonnets that hint strongly at a certain profile, and as I have mentioned on one or two occasions, there will of course be an episode dedicated entirely to this particular question: who is the 'Fair Youth'? and to the equally, if not even more important question, to what extent can we even begin to hope to answer this. So delving into too much detail at this juncture would inevitably go too far, since we simply haven't gathered all of the evidence that is contained in these sonnets yet; but why not take this opportunity to recap just very briefly what we have gleaned so far. And if this is the first time you are listening to SONNETCAST you may either just note that that's where we are at, or there is always the option, of course, of going back and start at the beginning, though I will give you a few references that you may find particularly relevant.

What we know for certain is that the young man is both young and a man. We also know for certain that he is beautiful and considered to be beautiful by the world around him. We know that there is a world that takes note of him. This 'world' almost beyond doubt is London and London society. We know from Sonnet 3 that the young man addressed bears a striking enough resemblance to his mother for Shakespeare to make a point of saying so. Sonnet 20 corroborates this by telling the young man and us that he has "a woman's face," and on the way there, in Sonnet 13, we learn that the young man had a father rather than has one: his father is no longer alive.

We can not be certain that Sonnets 3, 13, and 20 are all addressed to the same young man, but all the indications we get – how he is described, how he is characterised – suggest that it is. If that is the case, then Shakespeare's young lover is, certainly at the time the first seventeen sonnets are composed, obstinate in his refusal to marry. Several sonnets – among them Sonnet 26 and Sonnet 40, to name but these – either directly address the young man, or refer to him, in terms that would be appropriate to a member of the aristocracy. This does not prove that he is a nobleman – Shakespeare could be using such language poetically or to flatter him – but it tallies with our perception overall that he very likely is. And remember that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. Plus, conveniently, there is at least one young Earl to whom all of the above apply.

Saying to a commoner – in the English class sense of a person who is not a member of the aristocracy – that they are 'common' is, even in Shakespeare's day, something of an insult. Shakespeare uses the word 'common' regularly in his plays, sometimes without giving it any particular value but applying it essentially mean 'commonplace' or 'frequent in appearance', and often as part of a disparaging term or phrase. 'Common prostitute' is an expression that was currency in English until relatively recently, and while he doesn't use the word 'prostitute' he does use "common whore" in Timon of Athens. It gives us a fair idea of what the adjective evoked even then. Cominius talks of "common muck," in Coriolanus, Coriolanus himself of "the common mouth," as something he despises; Hamlet speaks of "common players," and actors were, in Shakespeare's days, lumped together with rogues and vagabonds.

So telling a nobleman that he is growing common is strong stuff indeed. It is spectacularly brazen, especially coming from a commoner, like William Shakespeare. Of course, we could invert the argument and say: if it is such an extraordinarily offensive thing for a commoner like William Shakespeare to suggest to his young aristocrat lover that he 'grows common', then perhaps this indicates that the lover isn't a nobleman at all: surely Shakespeare wouldn't dare. Except he would, and he does. We have seen and heard him be remarkably outspoken to his young man before, and rather more significantly in the context of this particular sonnet: he is about to flip things around acrobatically with a sonnet that effectively exonerates him, and so he is clearly aware of the ramifications of what he is putting down on paper.

So, knowing that Sonnet 70 is about to follow, why make such a fuss about Sonnet 69? If all this poem does is set out one half of a whole that ultimately and taken together lauds the lover, then why would we feel the urge to give so much brain space and metaphorical airtime to a couple of lines that are about to be roundly relativised?

Because the gesture is so provocative. It reminds us of Sonnets 15 & 16 which form a similarly strongly connected pair, in which the first half can be read and understood entirely on its own, except for the fact that it makes for a breathtakingly bold and borderline bawdy offering, on which Shakespeare then claws back with a humility which in that case does not entirely manage to convince as sincere.

Whether or not Sonnet 70 is sincere remains to be seen, and we are just about to do so. But even if it is, and even if Sonnet 70 is so strongly tied to Sonnet 69 that looking at Sonnet 69 on its own with more than a cursory glance were found to be unreasonable bordering on ridiculous, we should still find ourselves wholly justified in asking once again: what brings this on? What has the young man done or is he said to have done to invite such stench upon his reputation? Even if William Shakespeare himself does not believe, or agree with, any of the manure these tongues spread about his young man, what prompts him to write a poem that sounds – at the very least for the while we are reading, reciting, hearing it – as if he did? Why would a writer as expert and as skilful as Shakespeare lead us to believe, even for a moment, that there may be something to these rumours? Why would he talk about them in the first place?

As so often, alas, we don't know. What we do know is that with Sonnets 69 & 70 we have a sensational pair of poems of which the one we've just been discussing, Sonnet 69, tells at the very least, but also possibly at the very most, half of the story...

Once again, and as on previous occasions, we will be looking at the two sonnets together, much as they demand, in the next episode, while concentrating on Sonnet 69 for just now.

By some margin the most eye-catching moment in this poem comes at the very end with the closing couplet:

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

Why is this so outrageous? Because in this couple of lines Shakespeare is telling the young man that in the eyes of the world he is 'growing common'. That in itself would be fairly remarkable, but he does not make any attempt, it seems, to really soften that blow. The only indication in this poem that he may not entirely agree with this assessment of the young man's conduct by a censorious world comes in the preantepenultimate line where he calls either the people denigrating the young man's reputation churls, or their thoughts. But 'churl' is not a very serious term. Its meaning is either 'peasant' or 'miser'. In Sonnet 1, he calls the young man himself a "tender churl" for holding on to his own procreation potential; in Sonnet 32 he speaks of a time "When that churl Death my bones in dust shall cover," and even Juliet, upon finding that her Romeo has killed himself with poison calls him a 'churl' for having left no drop for her to do likewise. And here in Sonnet 69, beyond this mild, in certain circumstances even tender, term of admonishment, he does not coach his language in any way to make it clear that this is just what the world thinks and not something he agrees with. In fact the opposite. The way this is phrased the sonnets states as well nigh categorically that this is the real, so as not to say obvious, reason why his reputation reeks.

But such an accusation – even if it is cited or repeated from other sources – becomes even more extraordinary once we consider who the likely recipient is of these lines. The sonnet of course doesn't tell us, and we are in no position yet to make any firm pronouncements on the identity of this young man, nor are we ever likely to get any solid, irrefutable, material evidence that will confirm once and for all whom we are dealing with. But what we can say with a by now appreciable level of confidence is that we are looking at a young nobleman.

We have, throughout this podcast so far, found clues dotted around these sonnets that hint strongly at a certain profile, and as I have mentioned on one or two occasions, there will of course be an episode dedicated entirely to this particular question: who is the 'Fair Youth'? and to the equally, if not even more important question, to what extent can we even begin to hope to answer this. So delving into too much detail at this juncture would inevitably go too far, since we simply haven't gathered all of the evidence that is contained in these sonnets yet; but why not take this opportunity to recap just very briefly what we have gleaned so far. And if this is the first time you are listening to SONNETCAST you may either just note that that's where we are at, or there is always the option, of course, of going back and start at the beginning, though I will give you a few references that you may find particularly relevant.

What we know for certain is that the young man is both young and a man. We also know for certain that he is beautiful and considered to be beautiful by the world around him. We know that there is a world that takes note of him. This 'world' almost beyond doubt is London and London society. We know from Sonnet 3 that the young man addressed bears a striking enough resemblance to his mother for Shakespeare to make a point of saying so. Sonnet 20 corroborates this by telling the young man and us that he has "a woman's face," and on the way there, in Sonnet 13, we learn that the young man had a father rather than has one: his father is no longer alive.

We can not be certain that Sonnets 3, 13, and 20 are all addressed to the same young man, but all the indications we get – how he is described, how he is characterised – suggest that it is. If that is the case, then Shakespeare's young lover is, certainly at the time the first seventeen sonnets are composed, obstinate in his refusal to marry. Several sonnets – among them Sonnet 26 and Sonnet 40, to name but these – either directly address the young man, or refer to him, in terms that would be appropriate to a member of the aristocracy. This does not prove that he is a nobleman – Shakespeare could be using such language poetically or to flatter him – but it tallies with our perception overall that he very likely is. And remember that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. Plus, conveniently, there is at least one young Earl to whom all of the above apply.

Saying to a commoner – in the English class sense of a person who is not a member of the aristocracy – that they are 'common' is, even in Shakespeare's day, something of an insult. Shakespeare uses the word 'common' regularly in his plays, sometimes without giving it any particular value but applying it essentially mean 'commonplace' or 'frequent in appearance', and often as part of a disparaging term or phrase. 'Common prostitute' is an expression that was currency in English until relatively recently, and while he doesn't use the word 'prostitute' he does use "common whore" in Timon of Athens. It gives us a fair idea of what the adjective evoked even then. Cominius talks of "common muck," in Coriolanus, Coriolanus himself of "the common mouth," as something he despises; Hamlet speaks of "common players," and actors were, in Shakespeare's days, lumped together with rogues and vagabonds.

So telling a nobleman that he is growing common is strong stuff indeed. It is spectacularly brazen, especially coming from a commoner, like William Shakespeare. Of course, we could invert the argument and say: if it is such an extraordinarily offensive thing for a commoner like William Shakespeare to suggest to his young aristocrat lover that he 'grows common', then perhaps this indicates that the lover isn't a nobleman at all: surely Shakespeare wouldn't dare. Except he would, and he does. We have seen and heard him be remarkably outspoken to his young man before, and rather more significantly in the context of this particular sonnet: he is about to flip things around acrobatically with a sonnet that effectively exonerates him, and so he is clearly aware of the ramifications of what he is putting down on paper.

So, knowing that Sonnet 70 is about to follow, why make such a fuss about Sonnet 69? If all this poem does is set out one half of a whole that ultimately and taken together lauds the lover, then why would we feel the urge to give so much brain space and metaphorical airtime to a couple of lines that are about to be roundly relativised?

Because the gesture is so provocative. It reminds us of Sonnets 15 & 16 which form a similarly strongly connected pair, in which the first half can be read and understood entirely on its own, except for the fact that it makes for a breathtakingly bold and borderline bawdy offering, on which Shakespeare then claws back with a humility which in that case does not entirely manage to convince as sincere.

Whether or not Sonnet 70 is sincere remains to be seen, and we are just about to do so. But even if it is, and even if Sonnet 70 is so strongly tied to Sonnet 69 that looking at Sonnet 69 on its own with more than a cursory glance were found to be unreasonable bordering on ridiculous, we should still find ourselves wholly justified in asking once again: what brings this on? What has the young man done or is he said to have done to invite such stench upon his reputation? Even if William Shakespeare himself does not believe, or agree with, any of the manure these tongues spread about his young man, what prompts him to write a poem that sounds – at the very least for the while we are reading, reciting, hearing it – as if he did? Why would a writer as expert and as skilful as Shakespeare lead us to believe, even for a moment, that there may be something to these rumours? Why would he talk about them in the first place?

As so often, alas, we don't know. What we do know is that with Sonnets 69 & 70 we have a sensational pair of poems of which the one we've just been discussing, Sonnet 69, tells at the very least, but also possibly at the very most, half of the story...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!