Sonnet 48: How Careful Was I When I Took My Way

|

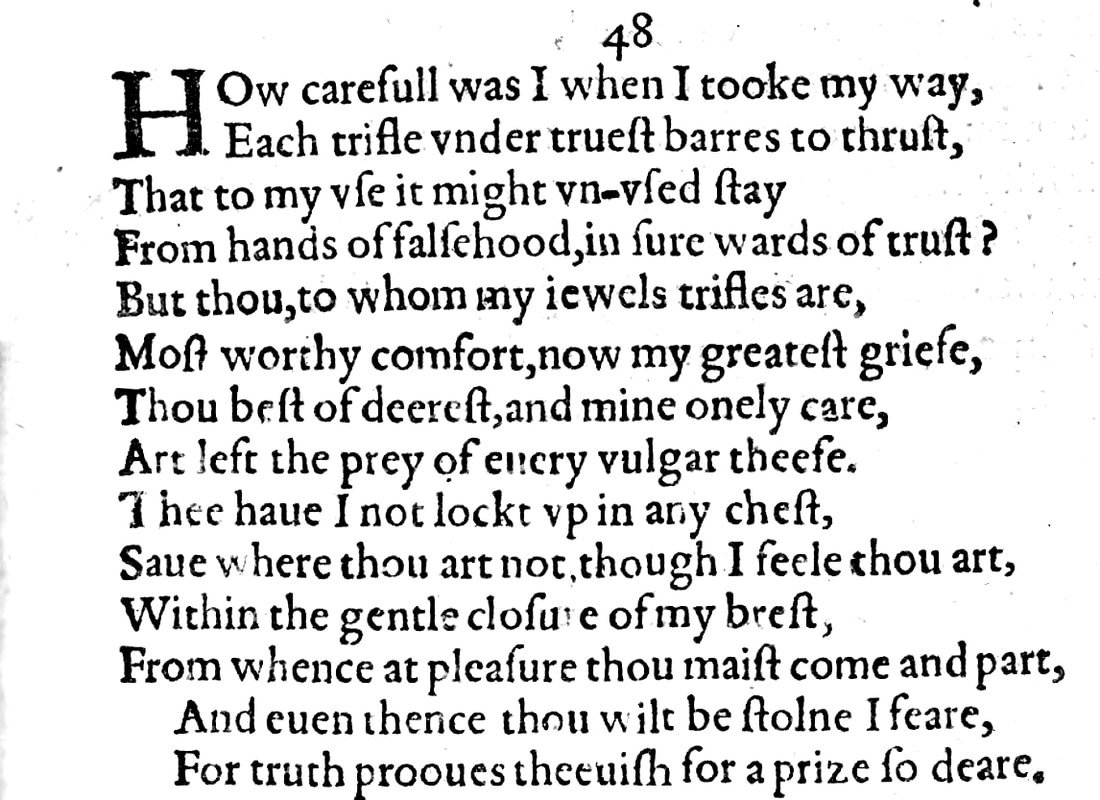

How careful was I when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust, That to my use it might unused stay From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust. But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are, Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief, Thou best of dearest, and mine only care, Art left the prey of every vulgar thief. Thee have I not locked up in any chest, Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art: Within the gentle closure of my breast, From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part, And even thence thou wilt be stolen, I fear, For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear. |

|

How careful was I when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust, |

How careful I was, when I went away on my journey, to make sure that every trifling little belonging of mine was safely under lock and key.

'Thrust' has a meaning of 'to cram' or 'to shove', which would appear to underline the notion that Shakespeare here is talking about things of insubstantial value. |

|

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust. |

So that when I come back home all of these things will still be there securely taken care of and so unused by anyone who might steal them.

'Hands of falsehood' are in effect unauthorised, untrustworthy, hands, the most immediate association for which is those of thieves, and the sonnet ends on a couplet which spells this out, as indeed does line 8 before then. And 'unused stay' for us today most obviously means that these objects remain untouched, but 'stay' in Shakespeare has a much stronger sense also of 'stay in place': the poet is principally making sure his stuff is still there when he gets back. |

|

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

|

But you, in comparison to whom my most valuable jewels are mere trifles...

|

|

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

|

...you who are my most valuable and esteemed source of comfort, but now through this absence turned into my greatest source of anxiety and worry...

|

|

Thou best of dearest and mine only care,

|

...you who are the best of my dearest, meaning the person I love most and the only one I care about,

|

|

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

|

You are left behind as the prey of every common thief.

We have come across 'vulgar' once or twice before, for example in Sonnet 38, where Shakespeare describes the young man's qualities as providing an argument "too excellent for every vulgar paper to rehearse," and here as there the term mostly means 'ordinary' or 'common', rather than, as we today would understand it, coarse and crude. |

|

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, thou I feel thou art: |

You, this most valuable, most precious 'thing' that I have, I have not locked up in any chest, except where I feel you are, even though you are not:...

Whether 'thou art not' here means 'you are not locked up there' or 'you are not there' makes a subtle difference and is not explained; and as so often, the double meaning is most likely intended, because Shakespeare can categorically say, as he does, that the young man ist not locked up in his chest, because, as the next two lines make clear, he may enter or leave this heart at will, but resulting directly from this freedom the young man has, Shakespeare is unable to say whether at any given moment the young man – as far as he, the young man, is concerned – actually finds himself there or whether he has already been taken away by someone else. |

|

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part, |

...namely within the gentle enclosure of my breast, meaning in my heart, from which you may come and go just as you please.

There is an obvious but still immensely gratifying pun on 'chest', of course, which can be a sturdy box or indeed a safe but also the human body's chest, where the heart is found, whereby the idea that the lover resides in the poet's heart is a well established trope. |

|

And even thence thou wilt be stolen, I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear. |

And even from there, from my heart, I fear you will be stolen, because even truthful and honest people turn into thieves for a prize as valuable as you are, meaning that there are just too many potential takers out there for this not to be the case

This alludes to the proverbial notion that, as John Kerrigan cites, "rich preys do make true men thieves," and places the young man firmly as the object of a feared seduction, rather than, say, as a person who may want to go astray. |

Sonnet 48 ends the emotional hiatus brought into the sequence by the previous five sonnets and plunges our poet back into a deep anxiety about how much he can trust that his lover will still be there when he returns from his trip. While it is not certain whether the sonnet sits in exactly the right place in the sequence, it fits with our perception that Shakespeare is still on an extended leave from London and expresses his worry – entirely justified in the light of what happened before – that his young man may be taken away from him while he is away.

Immediately striking about Sonnet 48 are two things: firstly we are right back in the thick of it. When Sonnets 43 through 47 allowed us detect a certain aloofness or detachment, for which we had no incontestable evidence or cause but which prompted us to speculate that Shakespeare may simply have resigned himself into the reality of a prolonged separation, Sonnet 48 is anything but uninvolved. Of course, it deploys some poetic devices such as the odd metaphor or trope, but it attempts no acrobatics, sets out no complex argumentation, and it categorically does not contend itself with exercising standard sonneteering themes. Here, what Stephen Regan in our conversation about the sonnet as a poetic form called the flawed character of the lover and the tarnished nature of the love come right back to the fore: rather than being able to go about my business with perhaps sorrow for being away from you but without any worry about your steadfastness and truth, as I have called it on numerous occasions, I am deeply concerned that you will be stolen from me.

And this takes us straight to the second point that catches the eye: Sonnets 33, 34, 35, and then 40, 41, and 42 all made unequivocally

clear the young man's responsibility for his actions and left no doubt that while Shakespeare was willing to forgive him for his transgression and even construct some fairly far-fetched rationalisation to help him do so, he also saw him as basically culpable and therefore in need of such forgiveness. Sonnet 48 casts the young man as prey: the most precious possession that is there for the taking, and yet if Shakespeare thus is trying to absolve the young man of any guilt for straying or straying again, he only, in fact, partially succeeds. More likely though, this is deliberate, because Shakespeare does tend to know what he is doing with words:

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part.

There is a mild admonishment contained in this. It is subtle enough, and perhaps it has to be, because we know this young man can be quite tetchy when it comes to being told what to do or what not to do, but the classical, traditional idea is: we two are lovers, I am in your heart as you are in mine. Shakespeare has said as much in Sonnet 22, although even there we ventured it may to some extent be wishful thinking. This points – and not for the first time – to an inherent imbalance in the relationship. I feel you are in my heart and I wish you were there and stayed there, but the fact of the matter is: you can come and go as you please. You are to my heart as a cat is to its 'owner': I may dote on you and adore you, but you come for your strokes and your food when you like, and when you've had enough you go elsewhere. And the choice of the word 'pleasure' here is telling. Relatively soon, in Sonnet 58, Shakespeare will concede that he is not to call into question the young lover's "pleasure, be it ill or well," inviting an implicitly sensual, in all likelihood sexual reading.

What Shakespeare with Sonnet 48 also does though, and this is equally noteworthy, is cast the young man as his. This may sound obvious, but is worth bringing to mind now and then, especially against the age-old question, what is the exact nature of their relationship. All of these sonnets that concern themselves with the young man's infidelity speak of a relationship which Shakespeare understands as an exclusive one. If that weren't the case, there could be no surprise, rage, despair, or indeed forgiveness, because there would be no trespass. And this sonnet again characterises the relationship as one which – as far as William Shakespeare is concerned – is or ought to be effectively monogamous. We know from the fact that it was a mistress of Shakespeare's with whom the young man has had an affair or a fling, that quite apart from being married in Stratford, he, Shakespeare himself, does not actually treat it as such, but, contradictory as this may be, the language of Sonnet 48 continues to paint a picture of a man who is genuinely in love, genuinely feels that his lover ought to stay true to him, and clearly fears that he may not.

And this doubt, this deep unease and evident awareness that the young man he wishes his may not be forever so will find most moving expression in the breathtaking, devastating sonnet that is just about to follow, Sonnet 49.

Immediately striking about Sonnet 48 are two things: firstly we are right back in the thick of it. When Sonnets 43 through 47 allowed us detect a certain aloofness or detachment, for which we had no incontestable evidence or cause but which prompted us to speculate that Shakespeare may simply have resigned himself into the reality of a prolonged separation, Sonnet 48 is anything but uninvolved. Of course, it deploys some poetic devices such as the odd metaphor or trope, but it attempts no acrobatics, sets out no complex argumentation, and it categorically does not contend itself with exercising standard sonneteering themes. Here, what Stephen Regan in our conversation about the sonnet as a poetic form called the flawed character of the lover and the tarnished nature of the love come right back to the fore: rather than being able to go about my business with perhaps sorrow for being away from you but without any worry about your steadfastness and truth, as I have called it on numerous occasions, I am deeply concerned that you will be stolen from me.

And this takes us straight to the second point that catches the eye: Sonnets 33, 34, 35, and then 40, 41, and 42 all made unequivocally

clear the young man's responsibility for his actions and left no doubt that while Shakespeare was willing to forgive him for his transgression and even construct some fairly far-fetched rationalisation to help him do so, he also saw him as basically culpable and therefore in need of such forgiveness. Sonnet 48 casts the young man as prey: the most precious possession that is there for the taking, and yet if Shakespeare thus is trying to absolve the young man of any guilt for straying or straying again, he only, in fact, partially succeeds. More likely though, this is deliberate, because Shakespeare does tend to know what he is doing with words:

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part.

There is a mild admonishment contained in this. It is subtle enough, and perhaps it has to be, because we know this young man can be quite tetchy when it comes to being told what to do or what not to do, but the classical, traditional idea is: we two are lovers, I am in your heart as you are in mine. Shakespeare has said as much in Sonnet 22, although even there we ventured it may to some extent be wishful thinking. This points – and not for the first time – to an inherent imbalance in the relationship. I feel you are in my heart and I wish you were there and stayed there, but the fact of the matter is: you can come and go as you please. You are to my heart as a cat is to its 'owner': I may dote on you and adore you, but you come for your strokes and your food when you like, and when you've had enough you go elsewhere. And the choice of the word 'pleasure' here is telling. Relatively soon, in Sonnet 58, Shakespeare will concede that he is not to call into question the young lover's "pleasure, be it ill or well," inviting an implicitly sensual, in all likelihood sexual reading.

What Shakespeare with Sonnet 48 also does though, and this is equally noteworthy, is cast the young man as his. This may sound obvious, but is worth bringing to mind now and then, especially against the age-old question, what is the exact nature of their relationship. All of these sonnets that concern themselves with the young man's infidelity speak of a relationship which Shakespeare understands as an exclusive one. If that weren't the case, there could be no surprise, rage, despair, or indeed forgiveness, because there would be no trespass. And this sonnet again characterises the relationship as one which – as far as William Shakespeare is concerned – is or ought to be effectively monogamous. We know from the fact that it was a mistress of Shakespeare's with whom the young man has had an affair or a fling, that quite apart from being married in Stratford, he, Shakespeare himself, does not actually treat it as such, but, contradictory as this may be, the language of Sonnet 48 continues to paint a picture of a man who is genuinely in love, genuinely feels that his lover ought to stay true to him, and clearly fears that he may not.

And this doubt, this deep unease and evident awareness that the young man he wishes his may not be forever so will find most moving expression in the breathtaking, devastating sonnet that is just about to follow, Sonnet 49.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!